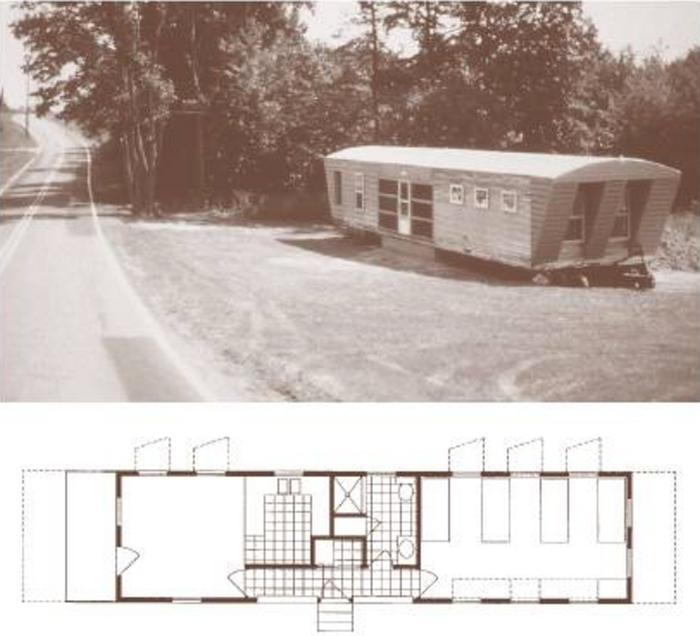

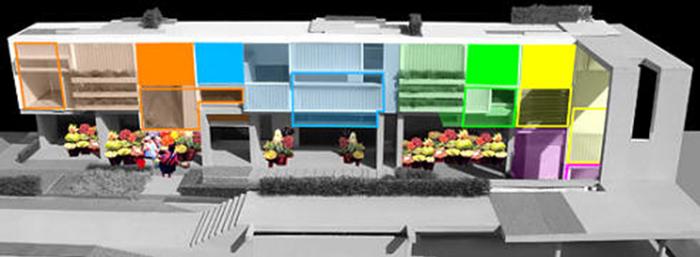

Julian Daly and Rebecca Sherouse EssayWithout a Home - Migrant Farmworkers in California“To work in architecture you are so much involved with society, with politics, with bureaucrats…” -Ai Weiwei To conceptualize this project, we initially sought to solely answer the question at hand. How to combat homelessness in our community? Both Southern California natives, we the authors were strongly drawn to the plight of the migrant worker. Affordability and habitability of farmworker housing in California is a state crisis, suffering from inhumane neglect by policy makers, residents, and California farm owners alike. Research shows that one-third of farmworkers live in places not meant for human habitation, and evidence points to statewide overcrowding, with shocking numbers of workers living in structures not considered safe for residential use such as cars, caves, tool sheds, and even mud huts (CDFA 2016). Rural poverty, specifically that of migrant farmworkers, has persisted for decades despite federal, state, local, and private efforts to confront the crisis. As residents of the state which produces over one-third of the countries vegetables, and two-thirds of the countries nuts and fruit, we have felt the direct benefits of this $54 billion dollar industry and the migrant workers that support it, stimulating our feeling of responsibility to combat the issue. As our research and proposal proceeded, however, our scope evolved and conception of combating homelessness shifted, forcing us to confront our responsibilities as architect, policy advocate, and members of our community to not only solve the issue at hand, but to do so in a compassionate, collaborative, and empowering way. In our research we do not wish to champion the fight against migrant worker homelessness alone, but to develop a methodology, based on our extensive interviews and research, that can be applied statewide to communities, organizations, and volunteers to harness existing forms of support to make dignified housing for migrant workers a reality we can be proud of. In order to impact society through architecture, we must first understand the needs of the group, especially as they transform through decades of cultural, economic and political shifts. It is imperative that, in the case of this essay, our architectural proposal is in line with the current lifestyle and demographics of migrant farmworkers. We must reject the outdated image of dust-bowl era labor camps. Only with an understanding of both the current state of migrant worker housing and their changing lifestyle, can we analyze architectural needs and subsequently assess current California policy. As globalization invigorates the California agricultural sector, the industry continues to prosper by transitioning to high-yield, high labor crops. This evolution, as coined by Professor Juan Vicente Palerm, is known as “the re-laborization of agriculture”, and explains that the duration of seasonal farm employment has become longer as farm production practices have changed. Today, demand for hired farm workers is higher than it has ever been in the past 100 years (Villarejo 2014). It is this demand, married with increased immigration regulation and consistently low-wages that has led migrant workers to settle in a specific area, instead of follow seasonal harvesting patterns or returning to home countries. Findings taken from 2007-2009 indicate that 70% of California’s crop workers are settled and living with family members in their home (Kissam 2013). Furthermore, a 5-year independent employment study taken by ACS says over 75% of agricultural workers reside in incorporated cities. These three drastic shifts in migrant worker lifestyle; 1) settling year-round in permanent dwellings, 2) living with at least one family member, and 3) living within an incorporated city, drastically changes the housing needs of migrant farm workers in California and helps us to shape a more comprehensive proposal. Migrant worker housing options are rapidly changing, city dwelling has become a norm as farms and labor camps do not provide adequate housing for seasonal employees. A 2012 survey of wages and benefits notes that only 3.6% of farms provide housing options to employees, mirroring a similar decline in registered farm labor camps from 5,000 in 1964 to 1,000 in 2000. While these options have effectively disappeared, there is only a marginal increase in number of subsidized farm housing developed by the government or nonprofit agencies. We have examined several types of government funding available to low income rural residents. The funds include USDA Rural Development (RD) 502 and 514/516 program, Low income tax housing credit (LIHTC) 4% and 9% low-income housing tax credits and finally The USDA’s Rural Development Farm Labor Housing program, which experiences enormous demand, as the state's total units are just over 5,500. Each of the government programs allow for different types of funding to families and quantity of housing made possible.The LIHTC 4% and 9% tax credits is the government’s largest program to support affordable housing, and provides funding for 90% of projects built. State architect Judy Moran oversees and approves all of these projects. From conversation with Ms. Moran we learned how the grants operate, the inner working are out of the scope of this essay but what results is large amounts of privately owned and operated affordable housing. Unfortunately, although many of these projects are in rural areas very few are designated as farmworker specific. As of 2009 California only guarantees $500,000 of the 120 million in tax deductions to farmworker housing (CST, 2016). While flawed, this system should be recognized and utilized more efficiently. In the 4% tax credit projects the architects we spoke to felt very limited by budget, usually only $30,000 per unit, this means almost all projects are remodels of existing buildings. After basic interiors and repairs to plumbing and electrical and there is very little money left for any massing or public areas changes. However, while The 9% tax credit developments are much fewer in quantity they can result in a much more comprehensive remodel. These projects often include use solar panels as well as outdoor community spaces (image 1). Different from these projects are the temporary migrant housing projects, run by the Office of Migrant Services (OMS), and funded by USDA’s RD fund. The government funding used to develop this housing has strict guidelines that can be difficult for workers to qualify for, some even having citizenship requirements. Criteria to apply to this temporary housing includes a limit of 180 days (extension possible but not guaranteed), restricted availability (not operational year round), and a distance mandate that states the family must live outside of a 50-mile radius for more than three months before moving in. Additionally, these dwellings are only available to families, promoting the epidemic of single farmworkers living in overcrowded, unsanitary apartments. Even with these potential drawbacks this program does provide many necessary services. The funds also allocate money to certain Community Programs. One project we visited in Shafter California has a large early childhood development center. Other than the development center the site lacked any community space, after visiting we both began to question; is simply providing habitation enough? Although the housing at the North Shafter California Labor Center was definitely habitable it did not address any of the farmers specific needs. The housing was prefabricated, the same two unit dwelling was arranged with no consideration to site context or desire to create public spaces (image 2). The site was removed from any basic infrastructure like grocery stores, medical clinics, schools, or public transit. It seemed to lack, in our opinion, any opportunity to establish a sense of community, network of peer support, or sense of pride in the home. The many housing options we researched prove to have positive attributes as well as core flaws. Having learned from both, we see a clear gap where there is potential for involvement and possible systemic change. Government funding is both a blessing and a curse, it can be very limiting in regulation but those regulations also mandate strict inspection, enforcing upkeep and habitability. Additionally the low funding per unit often produces a development that solely focuses on developing basic livable units. Following our research on farm worker needs and current systems in place, we look towards innovators in the architecture field who are championing the movement to provide migrant workers with more than just a temporary place to sleep. We have identified two architects that are working to give more to the families. The first architect interviewed was Bryan Bell, the head of Design Corps located in Pennsylvania. Although outside our direct community most funding programs are national, so the work being done in other parts of the country could be applied in California. Mr. Bell has written extensively on the subject of migrant farmers, and developed many projects for the farm worker population. In correspondence with him he casts doubts on the aforementioned Rural Development model. He pointed out rents for these housing units is established as a direct 30% of income. Due to this blind fee, meaning no other considerations are made on a family’s actual need basis, this housing is still out of range for some farmworkers. The result is farmworkers end up living in substandard housing conditions like tents and cars, while the rural development houses are sometimes left vacant. Bryan bell encourages a different government subsidy program; the Housing and Urban Development (HUD) HOME program. In this arrangement a partnership is set up between the farmer and the government, each split the cost of construction and the farmworker provides the land. After development the farmer is subject to strict guidelines and inspections ensuring continued care to the dwelling units and the farmer is forced to charge very minimal rent. Projects under this model are usually much smaller, since funds are split 50/50 between the farmer and the government, the scale of the projects is limited by the farmers ability to contribute. We see this as a benefit however because it allows for architects to consider local needs and conditions. It is a striking example of teamwork and cohesion between architect, government, and farm owner. The work Mr. Bell’s firm completed is a perfect example of how an architect can work on a small scale to solve this huge issue. Mr. Bell spent time in the field. Only after extensive research was he able to start designing a solution that would work for both involved parties. The resultant product was a house specifically for single migrating farmers. The design included storage units for tools, easy to clean dark surfaces, and bedrooms that allowed for multiple men to sleep in the same room while still providing privacy (image 3). This housing typology was well liked by both the farmworkers and the growers, however it should not be exactly replicated in California. The solution is based on the premise of migratory single farmers, but as we have stated farmworkers today are more likely to be living with a family and desire year-round housing. Although this goes against Mr. Bell's final solution, it does not go against the actual process of arriving at that solution. The architect is capable of working as a facilitator linking farmers in need of workers, with government subsidies. Through interaction with all involved parties, the architect, is capable of producing respectful architecture that responds to the users needs. This same process could be, but, as far as we can tell, has not been implemented in California. The second architect we spoke with is Teddy Cruz of Estudio Teddy Cruz in San Diego California. Mr. Cruz has done extensive work and research with the Latin immigrant population, although he mainly focuses on urban populations, similar to Mr. Bell, his approach and process can be applied to the rural population. One of Mr. Cruz’s main priorities is the importance of considerations other than solely housing when providing affordable housing to an impoverished sector of society. He says “it is not only roofs per acre but also interactions per acre” that must be considered in any design proposal. He argues for an approach to social architecture that creates community through social interaction. This type of design approach can most clearly be seen in his Casa Familiar project. Designed to be a senior citizen home the project incorporates many programs, such as communal kitchen gardens and dining spaces, all of which are useful and needed by the residents (image 4). The project is also a refurbishing of an existing building and takes advantage of state affordable housing programs, making it even more translatable to migrant family housing. These approaches, by Mr. Bell and Mr. Cruz, are where we see the most potential for improvement in affordable housing for low-income farmworkers. This is also where we see a potential for students, like ourselves, to be involved. We propose a system where research must be done and interviews conducted to find out what the farmworkers in each region actually need. Volunteer groups should act as facilitators and translators between the government, farm laborers, and farm owners to identify a win-win scenario where governments, private investors, and farm owners can work to provide funding for housing projects and create permanent subsidised need-based homes. We don’t need new policy measures instead involvement from people who care so that the the LIHTC tax credit system or the HUD Program, can be more effectively utilized. Policy research has uncovered that there is more potential for funding than is being taken advantage of in an innovative way. In the wake of cohesive data collection, funding, and logistical organization, architects can apply information from interviews and obtained grants and private funding to, like our two previously mentioned architects, create innovative and relevant migrant housing. A multi-disciplined approach to this problem is absolutely imperative, as one field, whether it be architects, government employees, or volunteers and advocates cannot access each of the necessary components alone. Teams, like ours, composed of both future architects and policy makers will be critical to address the distinct issues faced by farmworkers. Looking forward, we strive not to reinvent the wheel, but rather to use our research and fieldwork to empower and educate the incredibly well intentioned organizations, activists, and volunteers that fight against migrant worker homelessness every day. Our mission continues to be development of a cohesive plan of action that allows for open dialogue between migrant workers, architects, and government aid, identifying the most strategic and fair methods of funding, and finally operationalizing the vision to build physical structures that are dignified, sustainable, and functional. We want to provide a roadmap that can be implemented in different communities throughout California and be molded to the diversifying needs of farm workers and employers. We hope to provide a platform for communication between these varying entities, and work with the multitude of organizations that support migrant workers to work together in reshaping the landscape. Our passion has inspired us to work with volunteers to identify the true needs of migrant workers and farm employers, provide architects and city planners with that research, and to petition and take advantage of private and public funding to make this collaborative dream a reality. For full bibliography see email sent to info@berkeleyprize.org subject “Julian Daly and Rebecca Sherouse 2016 Essay prize bibliography” sent on February 1, 2016. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |