Required Reading - 1

THE POWER OF INCLUSION: An Introduction to BERKELEY PRIZE 2013

Elaine Ostroff, Honorary AIA

Remarkable as it might sound, within your lifetime, the understanding and definition of those who were formerly seen as “handicapped” has dramatically changed. The millennia-old medical emphasis, which focused on the limitations of our physically disabled relatives, friends, and neighbors and in the process often denied their rights, has been transformed. Today, accessible design and inclusive (or universal) design are the key phrases that point to an acceptance of the almost startling idea that “they” are “us.”

Accessible design says that every facet of the built environment should be able to be easily used by all of us. This is true whether we have full use of our bodies and minds or have some illness or accident that makes us temporarily dependent on crutches, or require, for instance, the long-term use of a walker or a wheelchair. Inclusive design takes the notion of accessibility one step further by giving it a new social dimension. As architects, we should not think of ourselves as designing special solutions for a particular sub-group of people, but for all of us. We are them.

One of the most visible indications of this shift in thinking is the adoption in 2006 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The Convention, which has now been signed by 153 countries, incorporates the World Health Organization’s (WHO) official redefinition of disability. WHO asserts that disability is not only a set of characteristics within the person; disability is increased or overcome by environmental conditions.

These are not abstract problems. Two statistics shine a spotlight on the problem: First, last year’s landmark World Report on Disability, produced jointly by WHO and the World Bank, estimates that more than a billion people in the world today experience disability. Second, this number is certain to increase even more dramatically in coming years. The world’s population of people over the age of 60 will double by 2050. These older persons experience functional disabilities at upwards of triple the rate of younger people.

This is a powerful international call for action and opportunity for architects to rethink their role in society and to more fully appreciate the power of design. As the creators of the physical environment, this is an extraordinary time for architects to work to create human-centered design that makes it possible for people of all abilities to participate fully in community life. Architects have the power to help create an inclusive city that improves all of our lives. You have the power to enable or to disable, to include or to exclude.

The American architectural journalist and current head of the American Institute of Architects, Robert Ivy, says it in a way that reaches out to all of us:

Have you ever broken your arm and tried to open a door? Been late for a plane and had to negotiate a crowded airport?…Struggled to understand direction signage in the streets of an unfamiliar city? Felt left out at a neighborhood meeting because you couldn’t see or hear the speaker? Reached to settle your belongings on a high self that lies just beyond your reach? If so, you have faced the consequences of design, an activity that has the power to affect our daily lives, for good or ill. (Foreword, Universal Design Handbook)

Inclusive design is an approach to making buildings and places that honors human diversity. It addresses the right for everyone from childhood into their older years to use all spaces, products and information in an independent and equal way. This is not simply compliance with regulations for accessibility, but re-imagining how accessibility could work.

The 2013 BERKELEY PRIZE asks what has been done and what more could be done in your community to create an inclusive city that welcomes and ennobles every person. As you look about your city using the eyes of a disabled person, what do you see? If you required a wheelchair to be mobile for either a day, a month, or your lifetime how would you get from Point “A” or Point “B”? Tell us about the journey. If you were blind, how would shop for your food, get to work, meet friends for entertainment and participate fully with them? Tell us about how your community has made these daily functions more accessible for all us.

Finally, tell us how all of these design interventions could be made even more inclusive and how.

___________________________________

* Click Here for the printed version of an illustrated power point presentation, American Diversity and Design: Aging, Design, and US Legislation by the author on the subject of universal design and a more thorough look at the statistics, particularly slides 13-20.

Elaine Ostroff, Hon. AIA, co-founded Boston-based Adaptive Environments in 1978. In 1989 she developed the Universal Design Education Project (UDEP) at Adaptive Environments. UDEP was a national project with design educators that has become an international model for infusing universal design in professional curriculum. She coined the term “user/expert” in 1995 to identify the individuals whose personal experiences give them unique critical capacity to evaluate environments. In 1998, she convened the Global Universal Design Education Network and its Online Newsletter. She stepped down as Executive Director in 1998 and now works as a consultant with the Institute for Human Centered Design/Adaptive Environments. There she directs the Access to Design Professions Project, with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. Access to Design Professions encourages people with disabilities to enter the design professions as a way to improve the practice of universal design.

The U.S. Association on Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD) honored her with their 2007 Achievement award. In 2006, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) awarded her an Honorary Member designation. In addition, she is the 2004 recipient of the British-based, international Misha Black Medal for Distinguished Services in Design Education – the first woman and the first American to receive that award. In 2003 Ostroff was awarded the (United States) Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Honorary Award. Ostroff was the Senior Editor of the Universal Design Handbook published by McGraw-Hill in 2001. She has her B.S from Brandeis University, an Ed.M from Harvard University and was a Radcliffe Institute Fellow in 1970-72.

|

|

|

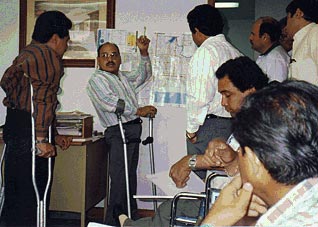

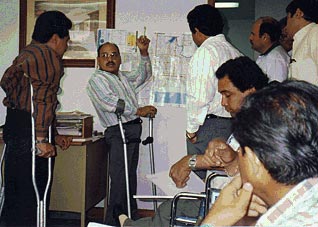

Like everyone else, this worker in Mexico needs transportation to his job. Public transport needs to be accessible for persons with mobility, sensory, and cognitive disabilities.  Persons with disabilities around the world are promoting transport systems that provide mobility for everyone. Mexican disability advocates are shown meeting with local transit officials to promote accessible transport. AEI has published guides to assist planners and advocates of inclusive transportation.  An accessible travel chain begins with safe streets and sidewalks. This street in Foshan, China, has separate rights-of-way for pedestrians, human-powered vehicles, and motor-powered vehicles.  Disability advisors at Rio de Janeiro’s Independent Living Center monitored access features for this street crossing, part of the Rio City Project.  Tactile guideways and tactile warning strips assist blind and sight-impaired pedestrians as well as others in Foshan, China.  Tactile warnings alert this blind person crossing a mid-street island in San Francisco, USA.  Busy intersections benefit from pedestrian controlled buttons and assist blind persons to cross through sound and vibration signals  Tactile warnings protect blind persons – and all other passengers – from getting too close to the platform edge in transit stations.  This footway adjacent to a road in Tanzania is protected by curb pieces which separate motor traffic from pedestrians and bicycles. Such basic safety measures are needed to prevent pedestrian injuries along roadways in many countries.  Even better, pedestrian and non-motorized traffic can be kept safely removed from motorized traffic by accessible sidewalks separated from the roadway, in this case by a well-designed drainage system along a main road in Tanzania. Speed bumps are used to slow traffic at crosswalks.  This pedestrian crosswalk provides level access to a bus island at an inter-modal transfer center in Mexico City.

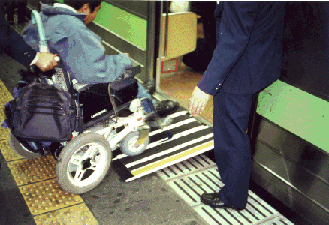

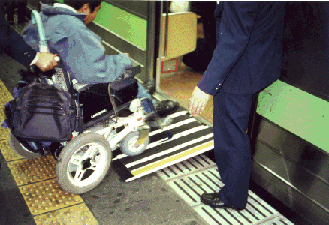

Photo by T. Rickert, courtesy of DFID (UK) and TRL (UK).  Ticket vending machines should be low enough for use by wheelchair users and all short persons, as illustrated by the good design of this machine at a BART station in the San Francisco Bay area, USA.  Stairs are often retrofitted with stair lifts in transit terminals, as here in a Tokyo subway station. However, in new construction, elevators should be considered where possible.  A wheelchair user takes the elevator from the platform level of the Shenzhen, China, railroad station.  Wide doors are needed to accommodate wheelchair riders entering fare-paid areas of transit terminals, as in this subway station in Rio de Janeiro.  Everyone can safely board this BART train, due to a minimal horizontal and vertical gap.  However, care must be taken that horizontal gaps are not too wide. The orange “gap filler” pops up when the doors open in San Francisco’s Muni Metro, assuring a safe gap.  Small portable ramps can provide inexpensive access in many rail stations, as shown here in Tokyo.  All passengers, and especially deaf and hard-of-hearing passengers, benefit from well-located visual information, as with this route display on board a train to the Hong Kong airport.  Advocates Anjlee Agarwal (left) and Sanjeev Sachdeva board the accessible Delhi Metro on its inaugural run.

Photo courtesy of Sanjay Sakaria and Samarthya, from Amar Ujjala Indian Daily  Express buses in Curitiba, Brazil, exemplify universal design. All passengers, including those with disabilities, quickly board with level entry. Similar Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems operate in Quito, Ecuador; Bogota, Colombia, and a growing number of cities around the world.

Photo by Charles Wright, Inter-American Development Bank.  Construction of this Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) trunk line corridor in Pereira, Colombia, symbolizes the rapid spread of BRT systems around the world. BRT systems lend themselves to universal design, but details must be monitored carefully to maximize accessibility.  Although most BRT busways are on broad thoroughfares, this exclusive single-direction bus lane nearing completion in Pereira illustrates that BRT systems can sometimes be built on narrow streets.

This and above photo by T. Rickert courtesy of World Bank  The photo shows an articulated bus docking at a Bus Rapid Transit station in León, Mexico.  Pre-paid passengers inside a station board a high-capacity BRT bus in León.

This and above photo courtesy of Sistema Integrado de Transporte Masivo de León  A prototype low-floor bus is tested in New Delhi adjacent to a platform the same height as the bus floor.  A closeup of the same bus stop illustrates the advantages of fast boarding for all passengers from platforms that eliminate the need for climbing steps to board.

This and above photo courtesy of Gerhard Menckhoff of the World Bank.  This prototype lift-equipped bus serves Mamelodi Township in South Africa. Note the excellent use of contrasting colors.

Photo by T. Rickert, courtesy of DFID (UK) and TRL (UK).  Mexico City officials inaugurated service in 2001 with 50 new buses equipped with lifts and other access features.

Photo courtesy of Marìa Eugenia Antunez.  In addition to a wheelchair lift, this bus in Mexico City has a retractable step beneath the front entrance.  This low-floor bus in Warsaw, Poland, uses an inexpensive hinged ramp which provides easy boarding for passengers with disabilities.  A low-floor bus in Hong Kong also exhibits excellent color contrast, using a bright yellow on key edges and surfaces.  Transit systems around the world have reserved seating for seniors and passengers with disabilities, and often for pregnant women as well, as found on this TransMilenio bus in Bogotá, Colombia.  Even when bus stops are not accessible to wheelchair users, access for seniors and others with disabilities can be enhanced by a level all-weather pad even in the absence of paved sidewalks. The photo is from a TransMilenio feeder route in Bogotá.

This and above photo by T. Rickert courtesy of World Bank.  Thousands of Mexico City’s small inaccessible microbuses are being recycled and replaced with larger vehicles, often with better access features.  One such feature is this priority seating located behind the driver where there is extra leg room and it is easier for blind passengers to hear the driver call out key stops.

Photo by T. Rickert, courtesy of DFID (UK) and TRL (UK).  In other new buses in Mexico City, a wide rear door has low steps and is easily accessed by semi-ambulatory passengers from a raised sidewalk, but requires that drivers carefully pull in to the curb.

Photo by T. Rickert, courtesy of DFID (UK) and TRL (UK).  Community initiatives are playing a growing role in providing accessible door-to-door transport in many countries. This accessible van in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, belongs to the six-vehicle fleet of Persatuan Mobiliti.

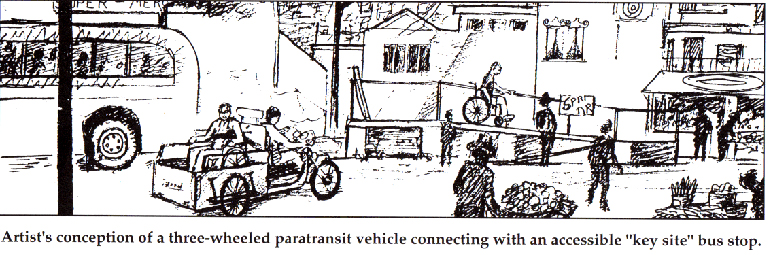

Photo courtesy of Persatuan Mobiliti  Artist’s conception of a three-wheeled door-to-door vehicle connecting with an accessible ramped platform with bridge at a bus stop at a key site.  This prototype three-wheeled vehicle was built with AEI’s assistance by Kepha Motorbikes in Nairobi, Kenya.  Detail showing entry via a ramp at the rear of the test vehicle.

This and above photo courtesy of Wycliffe Kepha.  This accessible bicycle rickshaw in India has a rear door which serves as a ramp.

Photo courtesy of Bikash Bharati Welfare Society and Lalita Sen.  A public meeting in Cali, Colombia, discusses accessibility to Bus Rapid Transit systems. Readers can go to the Bus Rapid Transit Accessibility Guidelines in our Resources section, under the links to the World Bank.

Photo by T. Rickert, courtesy of the World Bank.  In this version, the bridge piece is mounted under the platform and put into place by the bus driver.

This and above photo courtesy of DFID (UK) and CSIR Transportek (South Africa).  This test in South Africa of a prototype platform for use at key sites shows an alternative approach to access for wheelchair users.

|

|