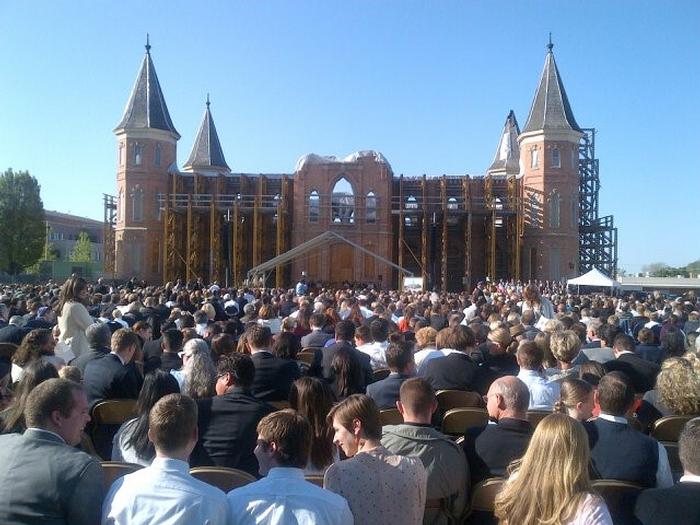

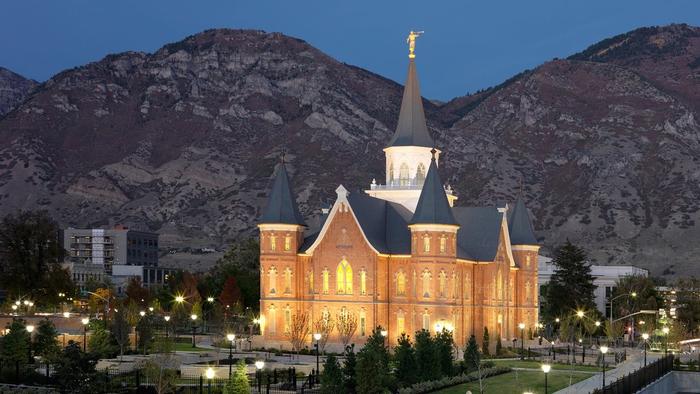

Layton Checketts EssayStories of Community: The Provo Tabernacle4 am December 17, 2010, downtown Provo, Utah. Dark smoke billowed from the Tabernacle’s roof. The blazing fire inside was in stark contrast to the sleepy, snow-covered town. The few people who saw the firefighters working prayed that the fire would be out and the incident over by sunrise. When Provo awoke that morning, despite firefighter’s best efforts, the Tabernacle’s roof had caved in. The fire continued throughout the day and by the time it was extinguished the beautifully handcrafted exterior brick walls were all that remained of the 124-year-old historic building. The Tabernacle had burned. It wasn’t just a piece of news the town heard, talked about and soon forgot in the work of the day, it was something that deeply affected the whole city. “We all felt like a family member died”, remembers Courtney Kendrick, Provo Community Outreach Director (1). Two days later on December 19th thousands of Provo residents gathered at the local University events center to hold a memorial service to mourn their loss and share memories of the Tabernacle. At the service, Utah congressman Jason Chaffetz expressed, “this is more than a building-it's part of our heritage. If you've lived in this community, you have had a memory there” (2). It has been said that the most sustainable architecture is the architecture that the public loves, because they will keep and protect it. In order to increase quality of life, unity of communities, and environmental responsibility it is necessary that we build buildings that last: buildings that do more than just perform their functions for 20 or 30 years then are torn down to be replaced at great material cost. We need buildings like the Provo Tabernacle to which people feel so connected, they would mourn its loss. How could a building be so beloved to this many people? Was it the prominent location of the structure in downtown Provo? Many well-situated buildings have failed in similar prime locations. Was it the fact that it performed its programmatic functions so well? DMV’s perform their functions well but no one would say that they were beloved by the community. Was it so adored because of its majestic handcrafted architecture? We all know that many architectural treasures have been demolished well before their time because their usefulness to the public was deemed lacking. The tabernacle was a successful and long-lasting building because it truly represented its community; their ideals and histories. I think to more thoroughly understand the reason behind the longevity and communal significance of the Provo Tabernacle you need to know the building’s full story. I hope that by gaining some insight from the Tabernacle we can apply this to future projects and create sustainable buildings that have a lasting positive impact in our communities. Although today Provo, Utah has an increasingly diverse demographic, it’s history is very much intertwined with the history of the pioneer Mormons that settled Utah. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, or Mormons, originated on the East Coast but due to great persecution they were forced to abandon their homes several times before they made their way westward to pursue religious freedom. After arriving in Salt Lake City, the Mormon prophet at the time, Brigham Young, sent many groups of families to settle the surrounding territories. In 1843 Brigham Young sent 33 families 45 miles south of Salt Lake to found Fort Utah, which later became Provo (3). As a result of being driven from state to state and home to home, Mormons became, by necessity and by nature, exceptional planners and builders. And their doctrine reflected the importance to build strong communities and cities. Things like crop failures, development plans, and community needs were discussed from the pulpit, blurring the lines between temporal and spiritual (4). Key to Mormon doctrine is the establishment of Zion. Although Zion is now less connected to a physical place than to a state of being, originally Zion was as much a way of constructing and running cities, as it was a state of righteous living. The first Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, had a plan for the ideal city, called the Plat of the City of Zion that included a master plan with community buildings and the temple occupying central plots. In this vision of Zion, “no separation existed between the sacred and the secular; rather all aspects of life, from the most routine to the most holy, were crucial to the work of salvation” (4). Communal building was and is central to Mormon doctrine. As with most religions there is a hierarchy of building typologies in Mormon construction. The first and most basic is local meetinghouses, where members meet weekly for church services. Another category, and the most elaborate of Mormon architecture, are temples. Although originally temples served a diverse range of functions including as a community gathering place, over time they became dedicated as a location for performing holy ordinances. Due to the sacred nature of the ordinances, temples became accessible only to Mormons who are living the principles of the gospel and have a recommend to enter. As a result of the specialization of temples, a third building typology emerged; that of the tabernacle. Tabernacles are large multi-purpose meetinghouses where regional church conferences and other civic and cultural events could be held. They were some of the first public buildings built in early Utah towns and naturally the cities grew around them, connecting them to the center of activity. With the growth of the community at Provo in the late 1800’s a tabernacle became a necessity. The need for a larger meeting place was real and urgent and church leaders urged members to help with the construction. An article in the March 1886 Daily Inquirer newspaper remarked, “there is no part in the city that seems to be so busy as the Tabernacle block. About one hundred men are faithfully laboring, clearing up the debris, graveling the sidewalks, and putting the block into a very neat appearance...pushing the work necessary to be done so that the visitors to Conference may be comfortably seated” (1). The Provo Tabernacle was finished in 1886. Provo residents felt deeply connected to and proud of the construction of their Tabernacle. As explained by Brigham Young University anthropology professor Ryan W. Saltzgiver, “the Tabernacle was a symbol of Provo’s collective commitment to the gospel and to building Zion” (4). The plan of the Provo Tabernacle was rectangular and 160 feet by 88 feet. Most of the building contained a large auditorium with bench seating on the main floor facing the stand and choir, and benches on three sides of the room on the upper mezzanine level, allowing a seating capacity of 3,000. It is interesting to note the architectural similarities between the tabernacles spread all across the state and the fact that this basic plan has been in use since the early days of the church. There is no hierarchy in audience seating and little on the stand, as Mormons believe that all men are created equal and their leaders are unpaid volunteers, not elite clergymen. Behind the stand was a beautiful organ that the community raised funds for by putting on music events. The wood stand, choir chairs and organ made an elegant backdrop to meetings. The Tabernacle’s walls were constructed of handmade brick and had stained glass windows. The local craftsmen and builders put extra effort to make it beautiful to show respect for the purposes it would serve. There were 4 octagonal towers at the corners containing spiral staircases leading to the mezzanine seating area. The entrances faced the street and as the parking wasn’t right next to the building, it encouraged pedestrian traffic and mingling. I remember attending regional church conferences as a child, being very excited to climb up the spiral staircase in the tower to the upper level where our family always sat. My siblings and I always walked on the interior of the spiral where the stair tread was the smallest, and it felt like we were climbing a mountain. It was exhilarating to sit in the large structure, looking down as hundreds of people filed in for conference, the building filled with warm, colorful light filtering in through the windows. This building’s architecture successfully represented the community’s ideals of hard work, dedication to serving God, focus on community gathering, the importance of craftsmanship, and of welcoming all. The Provo Tabernacle was well utilized by the community, for plays, cultural events, concerts, funerals, and civic meetings. In 1909 US President William H Taft visited Provo on his campaign tour. One of the most memorable events held at the tabernacle was a performance by Sergei Rachmaninoff in 1938. In the later 1900’s Mormon authorities began allowing other religions to utilize the building for their meetings. It was used regularly for holiday mass and other events. In a speech at the 2010 Tabernacle memorial service Utah Valley University President Matthew Holland said, “the Tabernacle has been the place of my sweetest moments of communion with believers not of my particular faith...It was not only a beautiful, historic building, but a place where we were all part of a greater community’” (2). Last year 90-year-old Provo resident Patricia Pett wrote about her memories of the tabernacle, “our first-grade class took part in a program at the tabernacle, [we] marched to the music of Sousa’s song ‘Stars and Stripes Forever'...I have cherished and loved that building ever since” (2). From visits by US presidents to first grade music programs, the Provo Tabernacle has been the backdrop to many significant memories of Provo residents for years. This is what burned down that crisp December day. It seemed to Provo like they had lost their physical connection to these fond memories and of course they mourned. After a year of deliberating the future of the burned tabernacle, Mormon prophet Thomas S. Monson announced in the church’s 2011 worldwide, annual conference that they would be restoring the Tabernacle and converting it to a temple. There was a general sigh of relief around Provo that they would be getting their tabernacle back. Amidst the surprise and excitement at the announcement there were some that felt the news was bittersweet. As a temple, the building would now only be accessible to Mormons with temple recommends. It would no longer be accessible to the general public, including children under the age of 12, or used for community meetings. People were so emotional about the future of the tabernacle because it really meant something more than a Mormon meetinghouse to them, it was a symbol of Provo and a cornerstone of their community. The project architects and the LDS church put extensive effort into documenting the artifacts on the site, and researching the history of the tabernacle. The temple that stands today is a beautiful restoration of the Tabernacle in its original state, including the central tower that was removed in 1919 for structural issues. Although the new temple is no longer accessible to the entire community, it still continues to impact the community for good. As marriage ordinances are performed at temples, now walking past the restored temple you will likely see groups of happy families greeting brides and grooms as they exit the building. Kendrick reported that the influx of people coming to the temple has revitalized the previously struggling downtown and encouraged new businesses and development to the area (1). The Tabernacle continues to bring life to the community that gave it life 131 years ago. During the time that the Tabernacle was being renovated, the church built a new tabernacle; a modern building whose architecture resembles contemporary LDS meetinghouses more than the old Tabernacle. Although this building fulfills the requirements to provide a large enough place of gathering, it falls short architecturally. It does not follow the time tested basic tabernacle layout, with too many rooms and no entries directly into the auditorium, which limits the connection to the street and doesn’t encourage mingling. It is not located in a high-density area and has a large parking lot, making the area unfriendly for walking. The construction, although of high quality, is not anything particularly innovative or majestic. The stand seems to be designed with only Mormon church services in mind, not welcoming other social or civic events. In short, it looks like a Mormon church meant for Mormon activities. It doesn’t encourage people of all faiths to come, nor does it seem like a place for the whole community. Being in this sterile new church reminds me again of why being in the old Provo tabernacle felt different. Being in a structure that was truly built by and for your community connects you to your community. It makes you feel a part of something bigger; a part of a story. Entering the old Tabernacle you could feel the pioneer spirit and it made us gratefully proud of who we are and those who went before us. This is what enables buildings to last. When people feel that they are part of the building’s story, or even better, when they feel that the building is part of their story, then the building will stand the test of time. Now the challenge comes to determine how best to weave the public into that story. Some of it happens naturally over time, but some I believe architects and designers can and should work to influence. It happens when architects understand community ideals and integrate them into design. Every building has a story. Learning about and participating in those stories is a large part of what drew me to architecture. Nearly every building means something dear to someone somewhere. Someone dreamed that a building would be there. Someone labored to finance or do the construction, meticulously worked out the design and layout, coordinated with local government, and celebrated the day it opened. Inevitably those buildings embody their owner; their ideals, and goals. Even the somewhat decrepit retail store down the street might have been the realization of a long fought for dream by the owner, or the incongruous orientally themed Asian restaurant around the corner might be the symbol of freedom and means of life for an immigrant family. It seems that every building, even the most drab, has some unique back story that gives it life. While all buildings have a unique story, some are so clearly designed with the ideals of public that they are the story of not only of the builder and owner, but of the whole community. Such is the case of the Provo Tabernacle; a building that has captured the hearts of Provo residents for over 130 years. It is these socially responsive buildings we have the great opportunity and responsibility to design and build. By approaching building with the goal of adding to the community’s collective story by using design principles that match their ideals, we will create sustainable, lasting architecture.

References 1. Phone interview with Courtney Kendrick 1/5/2017 2. http://www.heraldextra.com/tabernacle/utah-county-residents-reminisce-during-provo-tabernacle-service/article_0dbe0cc7-3a2e-5aab-a71c-ee77b9229fac.html 3. http://www.provolibrary.com/historical-provo-timeline 4. http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4422/ 5. http://www.heraldextra.com/special-section/provocitycentertemple/story/provo-tabernacle-a-gem-in-utah-history/article_b3b92a15-8ca0-5d25-b499-f03cb28157cb.html 6. http://www.heraldextra.com/special-section/provocitycentertemple/story/provo-tabernacle-a-gem-in-utah-history/article_b3b92a15-8ca0-5d25-b499-f03cb28157cb.html 7. http://www.venitap.com/Utah/ProvoTabernacle/31Aug2002.jpg 8. https://mylifeinzion.com/tag/groundbreaking/ 9. https://i.ytimg.com/vi/MVoZ_5kGhqc/maxresdefault.jpg Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |