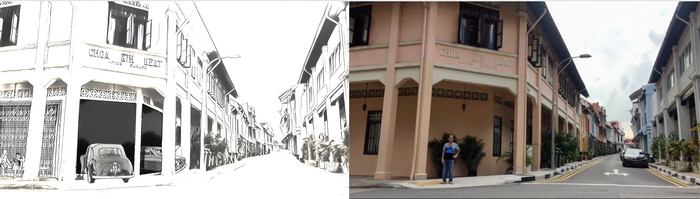

Hadi Osni EssayThe Baweanese Pondok: Pondok TampilungAbstract This article hopes to explore the “intangible practices of heritage“ (Harrison, 2010) of the Baweanese. This will be done through a close study of Pondok Tampilung, a pondok located at 39 & 40 Everton Road, and how the spaces in and around the building (i.e. a shophouse) was altered and adapted to meet the social, cultural and religious needs of not only its residents but also the Baweanese community at large. It is hoped that the consideration of the narratives of minority communities, such as the Baweanese, will paint a more nuanced and comprehensive picture of Singapore’s historic urban fabric as one that is truly a heterogeneous mosaic of cultures and religions. Background The Bawenese are a significant community that had migrated to Singapore from Pulau Bawean, an island off East Java, from as early as the 19th century (Nor-Afidah & Marsita, 2007). Upon their arrival on the shores of Singapore, most of the Baweanese would settle down in pondoks (meaning: lodging houses). These pondoks would usually be housed in various building typologies found in the old Singapore city at the time, such as the shophouse, compound house and Malay-type house. While most of these pondoks were believed to be largely concentrated in Kampong Kapor and Kampong Rochor, there were also many others scattered in others districts throughout the old Singapore city such as Kampong Pasiran and Everton Road (Nuradilah, 2011). After independence, in the1960s and 70s however, urban renewal in the Singapore city had prompted the relocation and dispersement of the Baweanese community into newer public housing estates around Singapore, as well as the demolishment of many building typologies that formerly housed these pondoks. Today, the buildings that formerly housed these pondoks, that still remain, have been conserved by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in historic districts. Most of these districts have been marketed by the Singapore Tourism Board (STB) as an attraction for cultural tourists. It is for these aforementioned reasons that I believe the Baweanese pondok is one that is worth exploring in detail, as it provides an example of how conservation efforts, though well-intended, may offer a skewed or oversimplified representations of the use of spaces. For instance, in 1989, URA embarked on a conservation effort in a "major effort to save old Singapore" (Aleshire, 1986). This effort primarily aimed to "to preserve not just the buildings, but also the street life in the areas" (Aleshire, 1986). It was through this conscious effort that some of the shophouses in historic districts such as Chinatown and Little India, where the pondoks were primarily found, were preserved. The problem, however, was that the narratives that came with these conserved spaces shone very little light and details on the livelihood of the early Baweanese communities who had inhabited and altered physical spaces. For instance, the five-foot way was simplistically explained as a state-mandated "sheltered passageway for pedestrians” (URA, 2016). Likewise, the back-lane is simply explained as another state mandated space that “provided for basic sanitation and to facilitate ventilation between rows of shophouses” (URA, 2016). Often left out are the social meanings imprinted on these seemingly functional physical spaces by the community that used to dwell in built heritage and are hence, consequently forgotten by tourists and locals alike. What is also worth noting is that despite it being an enclave for the Baweanese migrant community, the pondok is not recognised as an important feature in these historic districts. Arguably, this could be due to the fact that the STB had attempted to frame these aforementioned historic districts as mono-ethnic enclaves to provide a more compelling image for cultural tourists. For example, in Chinatown, the narrative that it was an enclave for the Chinese community is reinforced by embellishments in the form of Chinese-themed lanterns and signages along a row of shophouses that lead to the Chinatown Heritage Centre. As a result of the racialised representations of these historic districts, one plausible (albeit unfortunate) consequence is that cultural tourists may subconsciously attach an ethnic identity to the social history of building typologies such as the shophouse. With the absence of the former multi-ethnic composition and its vibrant street life, individuals may have been conditioned to look for features that allude to the historicity of a building typology by turning to 'tangible' objects such the preserved ornamented facades of the shophouses. Given these aforementioned realities, this essay thus seeks to inject the narratives and voices of the Baweanese community through looking at how the pondok served as an important social institution that played a key role in the integration of new Baweanese migrants into the country. This will be followed by a close study of Pondok Tampilung, the lodging house which primarily met the needs of the Tampilungs. It is through this case study that I hope to elucidate how the Baweanese had adapted and altered the existing shophouse which housed the pondok to ensure that it could meet the social, cultural and religious needs of its residents. Pondok: The Social Institution of the Baweanese Community Nor-Afidah (2007) noted that while the Baweanese had migrated to Singapore from as early as the 1820s, their migration only intensified in the early 20th century. As with many other ethnic groups in the Malay Archipelago, the Baweanese merantau (meaning: temporary migration) from Pulau Bawean to Singapore, a rapidly developing maritime port in Southeast Asia at that time, was driven by the search for better working opportunities. For some of the early Baweanese, the search for employment was driven by the desire to perform the haj pilgrimage, a compulsory tenet in Islam, of which majority of the Baweanese were (Kartini, 2015). Thus, they had intended to work in Singapore to amass enough savings to eventually make the voyage to Mecca from the Singapore harbour. Unfortunately, for most of them, their ambitions of performing the pilgrimage were left unrealised due to unforeseen circumstances such as the Japanese Occupation in the 1940s that had left most of them in a state of poverty, as well as the independence of the city-state that had restricted migration. It was for these aforementioned reasons that most of the Baweanese eventually laid their roots in Singapore. Initially, Baweanese from the same desa (meaning: district or village) would live together upon arriving in Singapore, primarily because they shared similar dialects, customs and religious practices. As migration from Pulau Bawean heightened in the early 20th Century (Nor-Afidah & Marsita, 2007), the Baweanese eventually established pondoks that mirrored their social structure back in Pulau Bawean. Headed by the Lurah (meaning: chief of a desa in Pulau Bawean), pondoks would usually be named after the desas from which they originated from (Kartini, 2015). Examples of such desas were Daun, Kelem, Sakauneng and Tampilung. As a result, new Baweanese immigrants would find their relatives in their respective pondoks upon their arrival in Singapore. The residents of the pondok would then be responsible for managing the welfare of the new migrants by providing them with accommodation as well as employment opportunities. It is for this reason that Baweanese migrants were often found in the same type of jobs, typically as drivers or syces (Nor-Afidah & Marsita, 2007). On top of providing new migrants with accommodation, it is also interesting to note that the Baweanese had also carved out spaces within the pondok to allow day-to-day communal functions to take place. This included communal spaces to entertain guests and receive new migrants, meetings to discuss everyday issues faced by the residents, as well as a surau (meaning: smaller mosque) for daily prayers and in some pondok the weekly congregational Friday prayers. From this, we can see how the pondok had functioned as a village outside the homeland to the Baweanese migrants. It is also for this reason that the Baweanese were a very close-knit community who had emulated the spirit camaraderie and togetherness, which was commonly referred to by the Baweanese as semangat gotong-royong. Pondok Tampilung Pondok Tampilung was located along Everton Road. It is situated in what is known today as the Blair Plain Residential Historic District which was gazetted for conservation by the Urban Redevelopment Authority in 1991. The district is surrounded by other historically significant areas, namely, Chinatown to the east. The shophouses in Blair Plain Residential Historic District in the 1920s initially housed affluent Chinese merchants and their families who had settled there to avoid the increasingly crowded Chinatown (URA, 2015). By the 1930s however, some of these shophouses were rented out to the Baweanse who established pondoks to meet the needs of the growing migrant community. Pondok Tampilung was among one the pondoks established along Everton Road. In the following paragraphs of this essay, I will delineate how the Tampilungs had resorted to altering and adapting spaces in and around the shophouse to meet the social, cultural and religious needs of its residents and the growing Baweanese migrant community at large. Social Needs: Accommodation for Residents Pondok Tampilung provided lodging for the Tampilungs who had difficulties getting their own accommodation — this typically refers to members who were not provided living arrangements by their employers (Kartini, 2015). At the same time, it also provided for family members who found themselves unemployed, by getting the other residents to chip in and bear the cost of rent and utilities until they found jobs. Over time, the high volume of Baweanse migrants eventually led to overcrowding in the pondok. As such, rooms within the shophouses had to be further sub-divided into “cubicles” (referred to as bilik) to accommodate for the high numbers. Such “cubicles”, meant for a single family, was about the length of a bed. In view of these limitations, married couples were usually given the upper floors of the shophouse for privacy. The communal spaces on the ground floor, which were typically used for social activities (e.g. entertaining guests and conducting prayers) during the day, functioned as sleeping quarters for the unmarried males at night. The need for space also resulted in the increasing significance of the five-foot way as a space for socialising. Ambins (meaning: low, wide and long benches) lined along the entrances of the shophouse. Adjacent to the ambins along the five-footway, the Tampilungs built a simple structure made of wooden columns and a zinc roof to shelter a stall. For extra income residents of the pondok sold traditional Malay food and desserts to the Baweanese and Chinese community in the district. This stall interestingly, also became an extension of the pondok, serving as an additional space for socialising. Also, as a number of the Tampilungs were drivers, the ground floor of the pondok was also used as a garage for their residents to park their cars after work (as seen in Fig. 1). Religious Needs: Religious centre for the Baweanese Community Ponduk Tampilung played the major role of being the religious centre for the Baweanese community along Everton Road. Mosques were relatively distant from the Blair Plain district. Therefore, the Tampilungs turned the rear court of the shophouse into a surau. The surau catered to the general Baweanese community, carrying out most of the functions of a typical mosque including the five daily prayers. Interestingly, the Baweanese used a kentong (a hollow piece of wood), striking it as a precursor to the azan, calling the surrounding Baweanese residents to the prayer. Such a ritual has become increasingly rare today and only practised in very few mosques in Singapore. The pondok also conducted Quranic recitation classes for children in the district. Furthermore, on important dates such as Eidul Fitr (the commemoration of the end of the Islamic fasting month of Ramadhan), the pondok held the Eid prayers, dedicating the whole ground floor of the shophouse to accommodate up to 300 congregants in commemoration of Islamic festivals. The surau was also used to conduct weekly meetings for the pondok residents. These meetings were usually headed by the Lurah to administer the affairs of the pondok. This included collecting rent, managing the general and personal affairs of the residents such as deaths, marriages, sickness as well as disagreements and fights (Kartini, 2015). Cultural Needs: Times of Celebration During special occasions such as weddings, the Tampilungs would erect temporary tents over the back-lane to turn the space into an area to host guests. In line with the notion of semangat gotong-royong, residents from surrounding pondoks will usually lend a helping hand, setting up temporary tables and chairs (as seen in Fig. 4). Additionally, they will help with the preparation and cooking of food and the back of the shophouse. The children, not to be left out, were tasked with serving the guests, bringing the food from the back to the front of the shophouse. Such special occasions would usually last a weekend, and it was a time when the Baweanese community would come together to provide mutual help and support. Conclusion In summary, the narratives of Pondok Tampilung along Everton Road paints a much more nuanced and comprehensive picture of the Blair Plains Residential Historic District than what is currently presented by the state. The summarised history of the district provided by URA, which they defined as an area “settled over time by the more well to do members of the Chinese merchant classes and their families”, leaves out the vibrant and spirited Tampilungs and the larger Baweanese community. Additionally, the altering and adapting of spaces in and around the shophouse to meet the social, cultural and religious needs of its residents and the growing Baweanese migrant community at large, brought life to what would have otherwise be seen by tourists and locals today as a mono-ethnic and a simplistically functional building typology. References Nuradilah Ramlan (2011) “Pondok Peranakan Gelam Club”, accessed February 25, 2016, from http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1791_2011-03-02.html Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman & Marsita Omar (2007) “The Baweanese (Boyanese)”, accessed February 25, 2016, from http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1069_2007-06-20.html Centre for Liveable Cities Singapore (2016) “Planning for Tourism: Creating a Vibrant Singapore”, accessed February 25, 2016, from http://www.clc.gov.sg/documents/uss/Plan-for-tourism.pdf URA (2016) “Blair Plain (includes Former Fairfield Methodist Girls' School)” accessed February 25, 2016, from https://www.ura.gov.sg/uol/conservation/conservation-xml.aspx?id=BLP URA (2016) “The Shophouse” accessed February 25, 2016, from https://www.ura.gov.sg/uol/conservation/vision-and-principles/The-Shophouse.aspx MalayHeritageFoundation (2014) “Life in a Baweanese Pondok“ accessed February 25, 2016, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRwwiaepy3o Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |