Essay QuestionARCHITECTS IN SERVICE TO THE COMMUNITY

QUESTION:As a future architect, what is the best way you can serve the needs of your local community?

SPECIAL BACKGROUND FOR BP2021: The core of the BERKELEY PRIZE is to require students to go out of their studios and into their immediate communities to talk to and learn from the people for whom they will one day design. This year because of the Covid-19 pandemic, such research is obviously not practical or even totally possible. At the same time, the PRIZE has produced 22 years of just such student research. Nearly all of this research is available on the BERKELEY PRIZE website. In addition, the subsequent professional work of many of the PRIZE winners has also been catalogued on the site. This year, we will use this storehouse of information and experience – the BERKELEY PRIZE Community - as the basis for your Essay Competition responses.

REQUIREMENTS: Become familiar with the history of the BERKELEY PRIZE, its many years of submissions and the research these submissions represent by exploring www.BerkeleyPrize.org. In particular, you are required to read the 20th Anniversary, BP2018 responses by some of the former PRIZE winners describing their then-current work and projects; current updates to this work; and accomplishments of other winners as found on social media. All of that can be found here. As a result of these readings, answer the Question using the following prompts to frame your response:

The following Introduction provides you with further background to this year’s topic and provides additional perspectives on architects in service to the community. INTRODUCTION: Vishaan Chakrabarti was named this past summer as the new William W. Wurster Dean of the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley. He is an American architect and professor and former New York City urban-planning official. Founder of Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, which is an architecture firm based in New York, he was named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 2018. He has published two books: A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America; and NYC 2040: Housing the Next One Million New Yorkers (co-author). Vishaan has given two TED talks: “How we can design timeless cities for our collective future.” and “3 ways we can redesign cities for equity and inclusion.” Both are also relevant to this year’s BP topic.

In addition, a recent in-depth New York Times article, “I’ve Seen a Future Without Cars, and It’s Amazing,” centers on Vishaan’s ideas.

Vishaan Chakrabarti

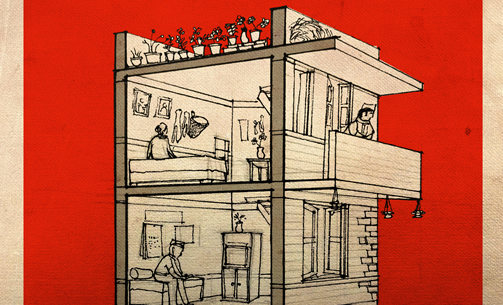

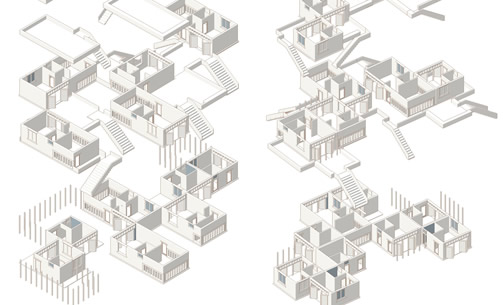

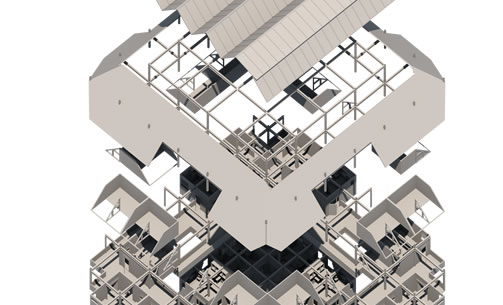

For decades, if not more, many architects have bemoaned their place in society. Concerned about low pay and disrespect from clients, many have suffered from low self-esteem, have argued that we should seize the means of production by embracing real estate development skills, or have moved away from the field altogether. Yet all of that feels like ancient history. Beset by a global pandemic, climate change, righteous calls for social and racial justice, and increasing scrutiny about the inequities both in and perpetuated by the field, architecture is clearly at a turning point. Some may continue to embrace the celebrity model of the profession that has dominated the field’s academic and media establishments but this would seem to be an unlikely focus for the upcoming generation, particularly at a place like Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design, a place that historically has eschewed the architectural establishment. But protest and rejection is not enough. President Obama asked us to define ourselves by what we are, not by what we are not. If the pursuit of architecture is not centered on the the goals of stardom and outsized commissions aimed to garner spectacular media spreads, or just as a simple means to make a living, upon what should it center? How is the profession relevant to the particular challenges of today—challenges like public health and climate change and racial equity—that in some cases will likely demand a century or more to address? Your essay could be a starting point to confront this question, a manifesto for why architecture is relevant to today’s world. Among the more unique aspects of the CED are the origin stories of our students, many of whom hail from historically marginalized communities. How could both an architectural education and the profession serve the kinds of communities from which many of our students come? If in those communities there are populations in need—communities of color that have suffered disproportionately from this pandemic, elderly or young populations with insufficient access to social infrastructure, or high numbers of individuals with physical or mental impairments, or a general lack of economic and educational opportunity fueled by racism and classism that has led to intergenerational poverty—what can architecture do? A rich territory to investigate would be to ask where most architects begin, which is the site analysis process itself. Diana Agrest has said to “write” in a place with architecture one must first “read” it. What are the processes for reading a place? Would you begin with community conversations? Historical research? Understanding of physical climate and context? And in so doing, what personal baggage, what unconscious bias, might you bring with you in your work? How, if we are to be relevant, can we take action while having this consciousness? Recently CED faculty member and renowned landscape architect Walter Hood has publicly criticized the term “placemaking,” arguing that the terminology, the pedagogy, and the practice of “making places” needs to be interrogated given the role such actions may have in the gentrification and displacement of communities who go unacknowledged in such a process. Ironically and historically, Berkeley was an epicenter of this terminology of placemaking, itself a revolution against the emphasis on neutral space (as opposed to place) that was once espoused by orthodox modernists and is still in vogue among some practitioners. So if Berkeley was once a place that mounted a challenge against the mainstream architectural practices of their day, could it do so again, and could it do so by mounting a challenge to its own revolution from decades ago? Perhaps one starting point could be the re-emergence among a variety of practitioners and thinkers about the early roots of places like Berkeley and MIT, namely the work of the so-called “humane” modernists such as the members of Team 10, Alvar Aalto, Kevin Lynch, and others who centered themselves on ideas of “structuralism” as put forth by thinkers like John Habraken. An advocate for a modernism of self-determination, Habraken argued for architectural processes that included communities as makers of form and creators of inhabitation and use. Aldo van Eyck, famed architect of this movement, famously argued for the importance of place and occasion over Sigfried Gideon’s emphasis on space and time, thus leading to the ideas of placemaking that came to dominate CED, ideas that clearly need to be re-examined in light of race, gender, colonial history, and economic disenfranchisement. With bridge figures from the Team 10 period like Pritzker laureate Balakrishna Doshi still forging ahead in the areas of low-income housing and community driven architecture, a new group of practitioners have emerged such as Tatiana Bilbao, Lacatan and Vassal, and Pritzker laureate Alejandro Aravena as thought leaders in a new structuralist movement intent on community self-determination with laser like focus on the marginalized, but without the dogmatic aspects of placemaking. Aravena’s now famous “half a house” project has emerged from the decades old “sites and services” paradigm in which community members are provided with core infrastructure upon which they are able to build and customize to suit their evolving needs. Markedly different from both celebrity architecture and the more romantic contextual concerns of placemaking, could a third way be emergent among a new group of architects who, while looking to the history of structuralism, are forging a new trail for not just architecture, but for the relevance of the architecture profession itself? Your essay could criticize this assertion, or investigate the work of such architects much further, or unearth yet the next generation of young practitioners who are taking this nascent movement and pushing it to a new level of relevance. Regardless of what aspect you might take on, perhaps the most important question for you to answer for yourself is what makes this field relevant for you as a student and as a future practitioner or scholar? What position do you hold for the field in light of the tremendous challenges society faces? Do you see the most effective methods for bringing change to be formal, sociological, technological, political, environmental, or through an entirely different lens? Perhaps the question of relevance, of effectiveness, of impact in the world, may itself be problematic. Perhaps you view the study of architecture as a path to a different type of awareness regardless of capacity for societal impact. But then what, in your view, is specific to the discipline and instrumentality of architecture to bring much-needed change to our troubled world, as opposed to the more general needs you might envision for political, social or economic transformation regardless of architecture? In short, why architecture?

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|