Lizzie Turac-EssayThe Built Environment’s Response to Aging in Place in Metro AtlantaTick.

Tock.

By 2030, 1 in 5 people in America will be over the age of 65, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 National Population Projections. For reference, that means there will be as many people over 65 as people under 18.

The average older adult faces difficulty maintaining physical, psychological, and social functioning. Consequently, the built environment cannot continue to ignore its senior citizens. Instead, it should employ strategies to alleviate barriers that hinder aging in place. The challenge is to design communities for the aging adult.

Time is of the essence.

For an adult to successfully age in place, cities must create comprehensive plans that address the lack of affordable housing, combat inaccessibility, and promote more effective means of public transportation. At the same time, the built environment must provide safety and prevent social isolation.

Without efficient measures, adults will one day reach an age where they no longer have their needs met by their built environment. They will continue to face a common ultimatum: relocate or lose their independence.

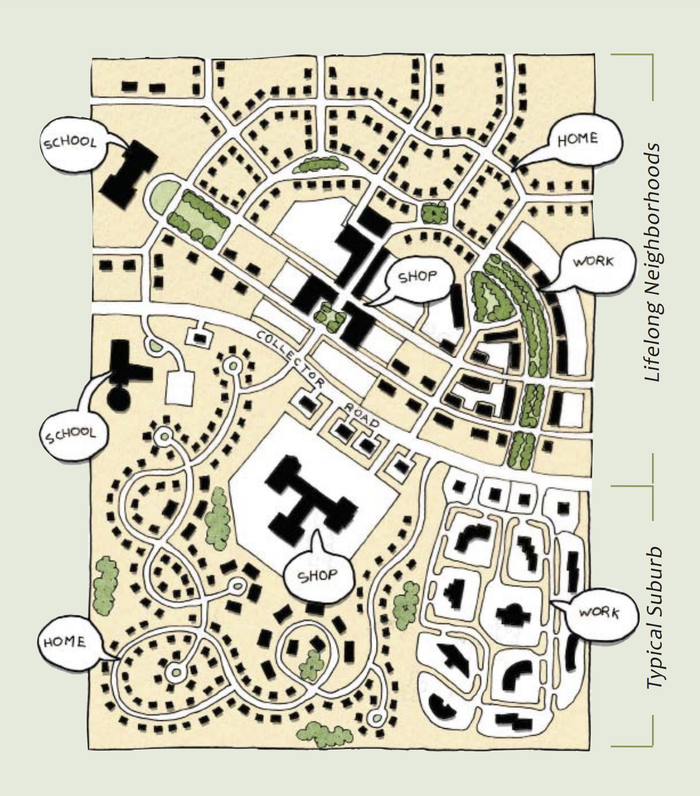

While these problems are nationwide, the senior citizens in Metro Atlanta are particularly disadvantaged because the region is predominantly composed of suburban communities which discourage walkability, development, and accessibility to services and resources close to home. More problematically, Metro Atlanta is comprised of diverse neighborhoods that lack public transportation connections, despite having a Metro system and the Beltline- a 22-mile track converted from previously unused railroad tracks that circles the core of the city.

Atlanta also struggles to provide affordable housing for its citizens, even though affordable housing was a critical component of the Beltline’s original design proposal.

All of these barriers significantly decrease senior citizens’ quality of life.

Fortunately, Metro Atlanta has not turned a blind eye to these issues. Architects, urban planners, medical professionals, and others are designing solutions through an interdisciplinary approach.

The Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) has implemented Lifelong Community Initiatives to improve the built environment and encourage aging in place. The initiatives follow a three-plan framework to provide affordable housing and transportation options, promote healthy lifestyles, and expand access to services. Today, Decatur and Mableton, Georgia serve as model example studies. Mableton has won numerous awards for its smart growth and active aging implementation.

The key takeaway from the Lifelong Community Initiatives is that everyone prospers by utilizing a universal design. What improves the quality of life for the aging population also benefits the younger generations.

One specific piece of architecture for aging in Atlanta is the Reynoldstown Senior Residences. It is located one block from the Beltline and was funded n part by a $1.5 million Beltline Affordable Housing Trust Fund grant. The residence successfully creates multigenerational connections to the rest of the city through its direct access to the Beltline.

By persistently improving the built environment through universal design and intergenerational services, communities within Metro Atlanta are promoting aging in place. What we design for senior citizens goes beyond just one demographic—the clock moves at the same pace for everyone. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |