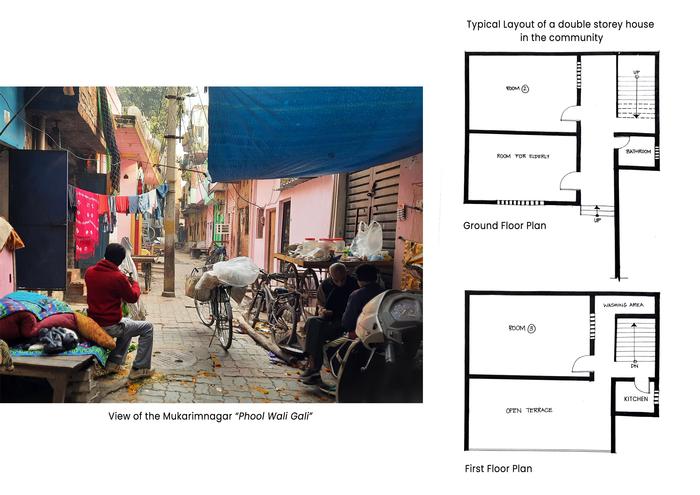

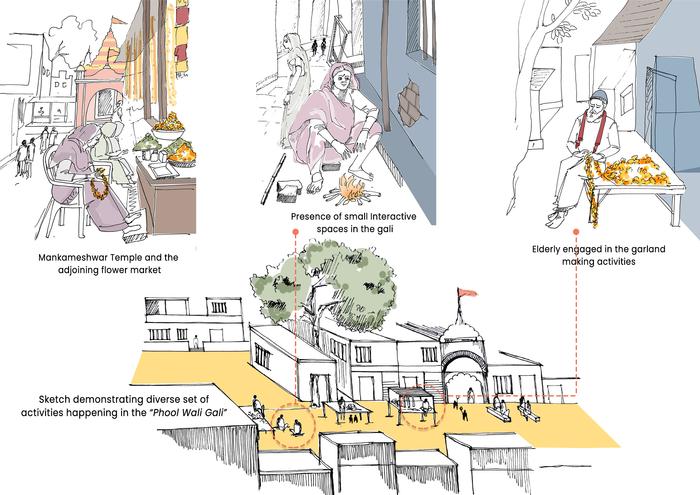

Ieshika Singh and Ashima Saini - EssayGreying Hair and Hopes: Senior Citizens of MukarimnagarAt 4 AM the rhythmic ringing of temple bells wakes up the small community of Mukarimnagar. There is a lazy bustle of movement around the Mankameshwar Mandir (mandir: temple) as flower and prasad (grace) vendors set up shops and worshippers stream into the temple complex. Mankameshwar, which refers to the god of wish fulfillment in Indian culture, attracts devotees from all the neighboring communities who come here to ask for a mannat, a wish. It symbolises hope for the people who believe in it. To an observer, this settlement seems like an ecosystem of its own, with the temple acting as the heart of all activity.

Nestled snugly along one of the banks of river Gomti in Uttar Pradesh, India, Mukarimnagar came into being by and large as a consequence of fishing activities that took place near the river. Over time, however, due to the development of the riverfront, these activities gradually ceased, leaving the residents of these fishing colonies to look for alternate sources of income.

The Elders of Mukarimnagar

Manning the prasad counters, sitting on the temple stairs, begging, or setting up shops early in the morning, the small community of Mukarimnagar is home to a large number of senior citizens engaged in the informal sector.

One such senior resident is Shrimati, a 72-year-old widowed mother, who is engaged in the flower business that employs most of the residents here. Sustained by the multitude of devotees that visit the temple every day, phool (flower) and prasad selling are two of the most flourishing businesses in the precinct. A typical street during the day is filled with people making garlands and other flower assortments sitting outside, or at the threshold of their houses. Shrimati, who lives with her 42-year-old, partially paralyzed son, is the only earning member in the small family of two. Her husband passed away back in 2009, leaving the mother and son to fend for themselves. Every morning, Shrimati wakes up at 4 AM, does the household chores, and then sets up her shop with the flower arrangements that she had worked on the day before as soon as the earliest devotees start to trickle in. As the day goes on and the crowd thins, her son takes over sitting at the shop and Shrimati moves back to sit on the charpai (a small bed) in front of her house to weave more garlands that will be sold the next day.

A few rows from there is one of the bigger houses in the neighborhood. It belongs to the family of 65-year-old Rani Devi. Rani Devi lives in a joint family with her son, daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren. Usually, in joint families, each member has a designated role. The earning hands are generally middle-aged members, whereas the elderly help take care of the children and overlook family affairs. However, in households such as these where multiple sources of income are a necessity, the elderly inevitably participate in economic activities, or rather, they don’t retire at all. Rani Devi contributes to her family’s income by selling flower garlands near the temple. After helping with the household chores, she sits on the small verandah outside her house and squints while she puts a thread through the needle, weaving dozens of flowers as they come together in a beautiful necklace.

Not far from Rani Devi’s place of work is the Manakmeshwar Mandir. Also, present right outside the temple is rows of beggars who will be distributed food and prasad once the prayers conclude. Among them, almost hidden behind the horde of beggars lining the temple steps, sits another elderly resident of Mukarimnagar. Up until 6 years ago, 68-year-old Hariram used to work as an auto-rickshaw driver, transporting kids to and from school. However, now that the auto-rickshaw has been sold, his only source of income is through begging. As for shelter, with no family or relatives to speak of, Hariram, with his limited belongings, lives in a makeshift rickshaw that he calls home for all means and purposes. Although the households nearby regularly provide him with two meals a day, through harsh summers and even harsher winters of Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, that rickshaw is his only layer of defense against the elements.

Sunset Years and Rising Suns

The streets of Mukarimnagar are filled with numerous Harirams, Shrimatis, and Rani Devis. For the elderly population of this economically weaker section, retirement is an alien concept. To keep themselves and their families afloat, the working members keep their jobs well past retirement age, usually, till they physically cannot work anymore. In cases like Hariram’s where a senior cannot work due to a social or financial factor, or due to physical limitations brought upon by aging, the elderly often have to look for alternative sources of income, which, in Hariram’s case, was begging.

India presently does not have adequate policies to support its elderly population or to provide them with decent social security post-retirement. The Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS) was launched in 1995. As per the scheme, senior persons below the poverty line, aged 60-79 years will receive a pension of Rs 200 (2.45 USD) per month, and those above 80 years of age will receive a pension of Rs 500 (6.13 USD) per month. The pension amount, however, in today’s economy, does not even begin to cover the living costs for a week, let alone a whole month. Furthermore, in informal sectors where the rate of morbidity is relatively higher, the intended benefits of such schemes are lost.

IGNOAPS is just one of the many policies whose benefits fail to realize the actual need. At the end of the day it boils down to the fact that while public sector workers at least get some sort of benefits post-retirement, informal sector workers such as those living in Mukarimnagar continue to work well after their retirement age to meet their daily needs.

Not only that, but the socio-economic structure also offers only a limited set of employment opportunities after a certain age. For the elderly residents of Mukarimnagar, these include brisk jobs such as rickshaw pulling, shopkeeping, begging, etc. Moreover, the morbid reality also calls attention to the living and working conditions, reflecting upon the domestic architecture of the community.

Most of the elderly who work in the informal sector here either reside in one of the tiny houses lining the narrow alleys that branch from the main roads or do not have a permanent shelter at all. In the latter case, streets, and if they are fortunate enough, thelas (handcarts used by street vendors) and rickshaws assume the dual role of being their source of income as well as of temporary abodes.

The plan of a typical house here consists of a common room on the ground floor which usually stores raw materials for the shops along with a room for the elderly, and a first floor consisting of living quarters, a kitchen, and a washing area. In most cases, this one house accommodates at least three generations within it. The congested houses along alleys lack not only lighting and ventilation but also community facilities such as drinking water, sanitation, planned streets, and open greens. The living conditions in Mukarimnagar hardly pass muster.

Furthermore, while most of the jobs are not particularly taxing, they demand infallible regularity. Shrimati, who earns around Rs. 150 (1.84 USD) to Rs. 200 (6.13 USD) a day by selling flowers, cannot afford a sick leave or she loses a day’s worth of income. At an age where physical ailments and illnesses are more frequent and intense, and proper healthcare is more of a necessity than an option, the elders here are expected to work everyday to make ends meet.

What the elderly of Mukarimnagar really need are fundamental things such as access to proper healthcare, financial and social security, and shelter over their heads. And yet, for them, old age is far from the comforts of retirement. It is a constant struggle to survive. Every night they sleep with the hope that the sun would rise brighter the next morning.

A Social Safety Net

While the situation seems incorrigibly dire, upon closer inspection, one realizes that this community has been able to sustain itself with the help of certain safety nets that protect its vulnerable sections.

For example, a typical day in the life of Rani Devi boasts of an active lifestyle filled with healthy interactions within the community, a sense of belonging that stems from the presence of fellow residents of the same age group as well as her history with the place, and the joys of living with family. Like many other South Asian countries, the joint family system is widely practised in India. Living with one’s parents is seen as the norm and as a result, elders are not left to fend for themselves as the children get their own jobs and families. Among other benefits, this has a direct bearing on the quality of life of elders after retirement.

In Mukarimnagar, while there are examples of parents being abandoned after the children move elsewhere either for work or family, there is a large percentage of senior citizens like Rani Devi who live in joint families as well. This reduces the need for dedicated care homes for the elderly while also ensuring their continued participation in society.

Another noteworthy observation here is that in cases like that of Hariram, where no family or local guardian can be identified, the community works in concert to cater to their basic needs. Every day the neighboring households deliver lunch and supper to Hariram without fail. When the mothers and fathers are not home, the older children of the household take up the responsibility to send the meals. Even at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, this practice was not abandoned. The rickshaw where the elder sleeps is also provided by one of the resident’s families. This shows how community living can create a strong social shell that not only sustains the society within, but acts as a precedent for solving larger inherent issues.

The Architecture of the People

Despite these small rebates, the architectural elixir that the grim condition of Mukarimnagar desperately needs, is non-existent. Rather, what we have is an amalgamation of social and architectural forces that offsets these gaps to an acceptable degree. And it is, in fact, quite thrilling to observe how, owing to this dynamic, the community functions as a unified entity to cater to its needs and serve the context as well.

Going back to the temple, one notes how the activities happening around and by virtue of the temple have a positive impact on the people and the place alike. The phool and prasad businesses that flourish because of the large number of devotees who visit the temple give employment to numerous residents in the neighborhood. Most of these people are senior citizens since work opportunities are very limited outside the community. This further results in the creation of entire streets, locally known as phool wali galiyan (flower streets), where one or two members from each household can be seen sitting in groups or at their thresholds, chatting and making garlands and bouquets. While this may not do anything to the open drains or heaps of litter stowed in corners, these activities transform streets into lively spaces of interaction. For the elderly, it is a practice that keeps them from being socially isolated, providing them with a platform to socialize with the rest of the community. Moreover, this informal routine encourages community living, which in turn ensures that even the elderly who don’t live with a guardian are looked after.

Phool wali galiyan have indirect benefits as well. Since these streets are active throughout the day, there are plenty of eyes on the street for petty crimes or thievery to take place in the neighborhood. Mukarimnagar, where a considerable percentage of the population is children and elderly, safety could have been a significant concern. However, owing to the nature of activities and their timelines, the neighborhood is not plagued by such issues, making it a peaceful place to reside not only for the elderly but for every other resident, regardless of their age group.

In one way or another, all these factors are related to the Mankameshwar Mandir. The social structure that has reshaped itself around the temple since the fishing colonies underwent transformation has made the community seamlessly adapt to the changes in the socio-economic fabric around the riverbanks. The temple serves the community by stimulating the economy of the area, generating employment opportunities for the senior section of society, and providing free of cost medical treatment to patients in the temple complex. These, in conjunction with social practices such as the joint family system, and looking after the senior citizens with no social or financial support on a community level, have made Mukarimnagar into a sort of social apparatus that is unquestionably capable of taking care of its elderly population no matter how dire the situation gets.

A Social Incubator

“People evolve first and systems later.” -Sukant Ratnakar

For architecture to serve the population, the participation of the community is imperative. This can be very well seen in Mukarimnagar where most of the elderly are engaged in the informal sector. Here, simply providing a nursing home or a care centre will not untangle the complex web of issues faced by the elderly population. And so, what we see instead, is the community stepping up to consolidate the intended goals of architecture.

Even though the infrastructure is lacking and the living conditions are subpar, making the place less than ideal for vulnerable sections of society like the children and elderly to live comfortably, the bonding within this small community has kept it afloat through difficult times. The pandemic years stand proof of that.

Rani Devi, when asked about her life in Mukarimnagar, gives a toothy smile and replies that there isn’t much to complain about. She is happy now that her son is married and settled with a family of his own. Her daughter-in-law is an agreeable cook and when it's not work, the kids keep her busy.

The lesson to be learned here is that answers are not always found in rigid boundaries rather, they can be discovered simply by letting life flow through.

References:

Goli, S. (2019) ‘Economic Independence and Social Security among India’s Elderly’, (39).

Prakash, I.J. (1999) Ageing in India. World Health Organization Geneva.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |