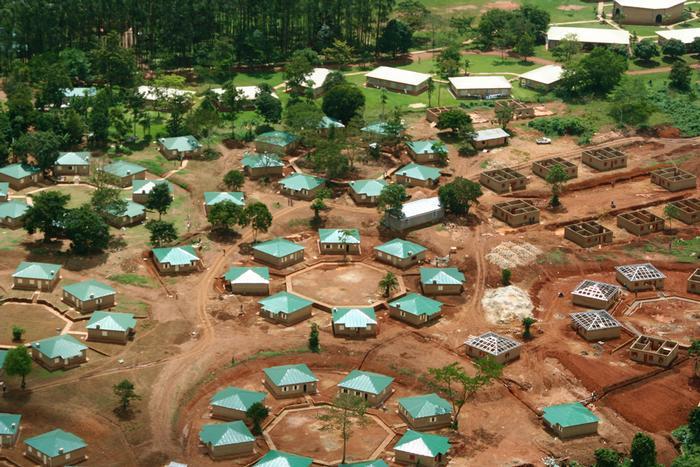

Bryans Mukasa EssaySUUBI; THE ARCHITECTURE OF HOPE“Architecture is not just one thing. It is not just an art. It has to deal with the real situation; it has to do something good for the society. Architecture can provide a better life for people.” (Xiaodu Lui) Apart from the inherent desire for shelter, history has shown that man builds for many reasons. Consider the Burj Khalifa in Dubai; we build high to conquer the sky. In Germany, the Reichstag is evidence that through architectural styles we express our political ideologies. Furthermore, the Washington monument is a reminder that architecture evokes a sense of awe in the populace through the sheer sizes. And when we travel to the Far East, we encounter the Great Wall of China, built with the aim of defining and defending territory (Crouch & Johnson, 2001). Indeed such examples and many more keep us wondering; “What is the principal objective of Architecture?” In my country, Uganda, we build to heal and restore hope. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, the northern part of the country has been devoid of holistic peace. The high prevailing HIV/AIDS epidemic and the Guerrilla war waged by the Lord’s Resistance Army have left scores homeless, orphaned and widowed. Besides providing aid, different childcare models have been developed with the very purpose of revitalising affected communities through architecture. But few of these models, speak the language of space as a healing tool so fluently and eloquently as my favourite rural destination. It is not filled with buildings as grand and sophisticated as many celebrated pieces of architecture. It is a simple place to live and yet with the power to stir the hearts of the orphans and widows who dwell in it to dream and to propel them to towards living their dreams. Suubi, which means hope in one of the local Bantu dialects, Luganda, is its name. Inspired by the African proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child,” it was established by Watoto Childcare Ministries in 1994 on Nsangi hill, fifteen Kilometres west of Kampala. It is symbolic of a traditional dwelling rising out of the African Savannah; attempting to amalgamate aspects of community life from various ethnic groups in Uganda. By striking a balance between the private and the public, inside and out, the African sense of community captured in the village provides not only the physical, but also the psychological ingredients required for the cognitive development of the children. The architectural ensemble is organised in clusters. Each cluster has nine homes, with eight of them arranged around a central space; the courtyard. The ninth house is slightly oriented and situated away from the courtyard to define hierarchy by placement. In it dwells the senior mother whose responsibility is to oversee other mothers within the cluster. She also plays the role equivalent to a Paramount Chief in a traditional Ugandan setting, representing the cluster at village gatherings and managerial level. The courtyard is a unifying multipurpose space, where communal social functions are sometimes held. On a daily basis, it is a place for children to play and interact safely away from the road. It is through the games played that learned values such as teamwork and cooperation are manifested. For instance, children from the same cluster form teams, majorly football for boys and dance groups for girls. They then challenge opponents from other clusters for the prestigious prize of “bragging rights”, as sixteen year old Tom, from Cluster 9 calls it. “It is a good feeling knowing that you are the best cluster in the village. Everyone wants to identify with you,” he adds. For a while my eyes are drawn towards the trees beyond the courtyard. I see children seated beneath the trees, rays of sunlight penetrating the foliage and hitting their faces. Then I look closer. With stained shirts, some up in tree branches, they are feasting on juicy mangoes like hungry monkeys while enjoying the football action in the courtyard. The children’s diet is supplemented by such fruits, which exist on trees planted throughout the village as part of the landscaping, primarily to provide shade and wood fuel. Among them I notice the lame cheering on too. Many sustained injuries during their lives as child soldiers. To enable them reach almost everywhere and get them involved in everyday activities, ramps are provided throughout the village. Furthermore, all activities in their homes are limited to the ground level. Perhaps for those who have made these homes their refuge, it is the perfect place to live. One that fits its inhabitants like a glove; one that is capable of adapting according to the needs of those who live in it, experience it day after day; one that gives them the freedom not to think, with every step taken, of their flaws and how to correct them; one that provides them with the opportunity to just be. When Tom and his peers are back in school, the character of the courtyard changes from being vibrant and noisy to a quite serene place. It is during these intervals that it becomes a place for the mothers to enjoy and reinforce the fundamental values tied to an extended family setting. In Suubi, as it is among the indigenous population, the metaphor of aunties, uncles, or cousins as distant relatives seldom exists. Everyone is as close as a brother or sister. Hence mothers feel obliged to watch over and discipline a child from a different home within the same cluster. In the courtyard, they hold informal meetings to seek advice on how to raise the children under their care, solve disputes, or even learn new entrepreneurial skills from each other. On a warm day, it is a place where they can hang clothes and farm produce to dry under the sun. A standard house is a simple cuboid with a pitched roof, approximately sixty four square metres. Although it is organised around a courtyard, its front faces the street with a flat one square metre metallic plate screwed on the wall. A house number is inscribed on the plate. This enables a visitor to easily identify the house he/she is intending to visit. On the part of family members, this coupled with the fact that no home is fenced, enables them to see a visitor from a distance. The children, especially those below twelve years sprint towards every one approaching with jolly but expectant facial expressions, hoping the person has carried some goodies for them. This moment of gladness creates a welcoming atmosphere around a visitor. Occasionally, I visit House 4 in cluster 9, where Tom resides. Off the largely public domain of the street, it takes approximately five strides along a concrete paved path to arrive at the door way. A simple knock at the steel door and chants of the children announce ones arrival. Kate, the house mother will then open and usher you in. Standing at the door way, you see the focal point of the home. It is the largest space and public realm of the house, accommodating the living and dining areas and surrounded by rooms on both sides. Its general layout enhances self- esteem and confidence by creating opportunities to do everyday things. For instance, it is furnished with lower worktops and cupboards to enable children to easily access items. Furthermore, the open plan space gives the flexibility for different uses- furniture can be moved aside should the residents want to dance or tables pushed together for a game of scrabble. The family’s socio-cultural traditions are visible in the general arrangement of decorative accessories with in this public realm. The composition suggests to the outside world something about the values, lifestyle and priorities of the people who live there. It is a place where the family spends most of its time together. As a result its floor is pale and faded, contrary to the rest of the dark red polished floor in the house. To enhance its aesthetic appeal, Kate partially furnished it with multi-coloured reed mats from one of her most prized collections of weaved crafts which she sells at the local market. It is three years since I first heard Tom’s story in this space and yet the images are still so fresh in my mind. He was abducted by rebels and robbed off his innocence, aged only ten. He watched his home burn to ashes, his mother being raped and killed. Then, he was subjected to a terrifying nomadic life in the jungle. Fortunately, he escaped during a raid on one of the communities and later found his way to Suubi with the help of a social worker. Since then, he has been on a journey of transformation and healing from a soldier to the normal child he once was. This has been aided by the village’s trauma rehabilitation regime consisting of weekly counselling sessions. His new home has also given him a sense of belonging. A family setting is purposely created so that the children learn to love and respect as they live with their mother and seven other siblings. In spite being an awesome footballer, he now proudly tells visitors, “When I grow up, I want to be President”. Kate, too, has her own story. She lost her entire family to HIV/AIDS. Left hopeless and lonely, she decided to join Suubi as a mother. ” I have made lots of friends in this village. I feel like I am living again. But that is not what matters,” she stresses, “when I see Tom and other kids under my care grow from miserable lads into happy and healthy fellows, I know that I have been part of something big; I have touched a life.” Left of the living area is the boys’ room. Out of curiosity, I once asked Tom why the boys stay close to the entrance and not their mum or elder sisters (whose rooms are on the right towards the dining table). He replied boastfully, “I think it is because we are strong, so we protect the house and the rest”. This response is not surprising since the belief that males are able to provide security due to their physique finds its genesis in various traditional homesteads in Uganda. The bedrooms provide more than just a place to rest. As Marshal (1997) suggests,” In a care home, there should be space for residents’ personal items, be it a favourite chair, or a pet budgie”. In Suubi, each child has their own bed and space to manage their belongings thereby building a sense of ownership and responsibility. Moving towards the door to the back of the house, another left turn brings one to the Kitchen. Unique to all kitchens in Suubi is the window overlooking the courtyard. Through it, a mother is able to monitor her children while they are playing. The walls enclosing the interior spaces also signal the spirit of the place. In an array of gloss and semi-gloss, shades of off-white cover the walls, speckled only by occasional faint fingerprints. Yet nothing obscures the whiteness of these walls quite as magnificently as what is up against them. The walls are hidden by nearly a dozen of posters of varying sizes and content, mostly expressing children’s political ideas, taste in music, or hobbies. As such, the walls reinforce personal identity. Besides those in the homes, the village empowers the local population socio-economically. By having additional community facilities such as playgrounds, multipurpose hall and health centre, the care village has become part of the local community. The village homes spill over into the neighbourhood allowing the orphans to interact and attend school with the rest of the children in the community. Moreover, the village is a source of employment to the locals, both at the construction and operational stages. As a result, community involvement in the project has helped to break perceptions of orphanages as institutions isolated from their neighbours. Building of the village is a continuous and collective effort, both locally and globally. The bricks used are made on site by members of the community, the roof structural elements are prefabricated at the local workshop, and each house is erected by teams from all over the world. Through the construction process, the community is directed towards a common cause. A variety of cultural or symbolic values are also expressed through the choice of materials. Built from earth bricks, the homes explore an ancient material rooted in local culture, while responding to the aspirations of contemporary Ugandan society through the use of modern materials such as iron sheets and steel trusses for the roof. The result is a harmonious blend of modernist sensibility, local craftsmanship, and indigenous knowledge. As Frank Lloyd Wright eloquently put it; "Architecture is essentially Human; it is the Human spirit manifesting itself. For when a Man builds, there, you've got him; you know exactly what, who and how that Man is." As a whole, I now appreciate the fact that a building's significance is not necessarily in its bricks or ability to excite masses, but rather in its power to evoke change. In a country where ethnic tensions are so pronounced, many believe that embracing architecture that transcends cultural differences will be one way of uniting the nation. I am not sure if I believe them. But Suubi village makes me want to. So appealing has the model been to the locals and international community that through strategic partnerships with organisations such as UNICEF, Watoto Childcare Ministries is planning to replicate it in formerly war-torn countries of Liberia and South Sudan. Nevertheless, the village has experienced numerous challenges over the years, with the greatest being the global credit crunch. This led to a reduction in financial support and frustrated efforts to expand the village. However, measures are being taken to forge a sustainable growth pattern. Among the initiatives underway is the recycling of biodegradable waste from village homes to produce biogas for domestic consumption hence reducing dependence on the costly hydro-electricity. Compost from the biogas facility will be given to the predominantly agro-based surrounding community, as fertilisers for their gardens. It is probable that this will consequently increase crop yields and so the neighbourhood will be in position to supply adequate food needed for the growing village population. By the year 2050, over four thousand former child soldiers and orphans from various ethnic backgrounds will have been nurtured by Suubi’s holistic social setting. Dreams embedded in the conscious and unconscious minds of the children, written on the walls of the houses and evident in the contagious smiles of young ones welcoming a visitor to their homes will have come to pass. Perhaps such success could ultimately enhance our understanding of the principal objective of architecture. Or if, in Tom, House 4 from Suubi produces a Ugandan President, his achievement will pose a question to all Built Environment professionals, “Suubi village changed my story, whose story will you change?” REFERENCES Crouch, D., and Johnson, G., 2001, Traditions in Architecture; Africa, America, Asia and Oceania. Oxford University Press: Oxford. Marshal et al., 1997, Design for Dementia. Hawker Publications: London.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |