Fathimath Ema Ziya - EssayThe Lost Children of the CitiesGrowing up in the Maldives, people expect me to have an idyllic childhood composed of postcard-worthy snapshots of paradise. However, what many people don't realize is that the Maldives is a nation with three faces. The face shown to the rest of the world is flawless; her natural beauty unabashedly spread across ads for 5-star resorts. The remaining two faces, seen almost exclusively by locals, stands in stark contrast to this image – hidden away from the tourists lest it taints the perfect face of the "sunny side of life".

“From now on, your only guardian is a neglected future.”

To a Young Poet, Mahmoud Darwish1

Here, the ordinarily crystal-clear waters can be murky, polluted by issues such as Islamic extremism. The nation's youth is a vulnerable portion of the community, at risk of falling and drowning in the dark depths. Without safe spaces that address the youth's needs, we can expect to lose more and more teenagers to these ruthless tides. This essay proposes to create sanctuaries for the youth, nation-wide, through a collaborative design process and youth empowerment programmes to secure a brighter, clearer future for them.

The face of Male’

Despite the problems with housing in Male', such as the exorbitant rate of rent, people from other islands continue to move to the capital due to the concentration of services here. This has led to a population density of 23,000 people per square kilometre. The dense urban landscape continues to develop at a break-neck pace, with buildings devouring the public realm like parasites. Many families live in poorly designed, cramped apartments leading to problems of privacy and space. For the youth growing up in Male’, the face they see is of narrow, congested streets with oppressive, looming buildings on either side.

Smells like teen spirit

There has been a rise in developing public spaces such as parks in recent years to combat these issues in Male’. Yet teenagers remain architecturally marginalized; too old to participate in these parks, yet too young to engage with the public realm as adults. For many of the city's youth, the only two spaces intentionally built for them are their schools and homes. The shunning of teenagers from public spaces and the labelling of them as trouble-makers can all be considered as disempowering measures taken against them under the misconception of deterring delinquent behaviour. Without spaces to safely socialize and interact with each other, they may struggle with feelings of isolation leading to other mental health problems. On the other hand, being at an extremely vulnerable and impressionable age, they could be led astray by iniquitous role models as they forge relationships in riskier settings. The rise in drug abuse amongst young people is an indication that teenagers find solace in these substances. Even more alarmingly, the increase in Islamic extremism and the youth's indoctrination presents evidence of the severity of the youth’s problem. This would be significantly worse for children who have issues at home or school, as they lack a sanctuary in the city.

Towards a new(er) architecture

Confronted with these issues and faced with the question of the architect's role in finding solutions, two dissenting approaches arise. The first adopts the "Howard Roarkian" approach; characterised by holding their education and truth above all else, single-mindedly finding and bestowing the solution upon the client. Continuing to embrace this "celebrity model" is not only an act of hubris but also rejects architecture as a social art and undermines the socio-political power of space. Instead, many architects have embraced a radical shift, advocating for community-led, collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches to the practice of architecture. They embrace the idea that the "right to the city is the right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart's desire"2.

Zuvaan

Following this radical shift, I propose to create 'sanctuaries for the youth' by consulting teenagers aged 13-18, to empower them to proclaim their "right to the city". An NGO called “zuvaan” - which means youth in Maldivian - will be set up to help youths achieve this vision. The organisation will implement the solution in 2 phases. Phase 1 will initially establish the organisation by creating a youth ‘sanctuary’ in Male' city. This will help garner support from society and gain volunteers for the programme. Then, phase 2 will focus on other atolls where more ‘sanctuaries’ will be created. The solution includes nine steps which are outlined below in order.

Phase 1

Step 1: One Man’s Trash is Another Man’s Treasure

Firstly, volunteer architects and teenagers will identify a site in Male' for the youth community hub. Male' is a tiny island with practically no undeveloped plots of land. Currently, most new construction in the city necessitates the demolition of an old building to pave the way for the new. For a country poised to suffer grievous consequences due to rising sea levels, this neglect shown towards sustainability in the construction industry is appalling. Instead of taking this destructive route, the organisation should opt for the adaptive re-use of an existing building. It sets a precedent for more sustainable buildings in the city. It also reinforces the idea of listening to the youth, as concerns for teens and the environment go hand in hand, clearly demonstrated by the Fridays for Future school-strikes initiated by students worldwide. Projects such as the Granby Winter Gardens in Liverpool by Assemble Architects have successfully transformed derelict spaces into community hubs, demonstrating how adaptive re-use adds value to the development3.

Step 2: The Humble Listener

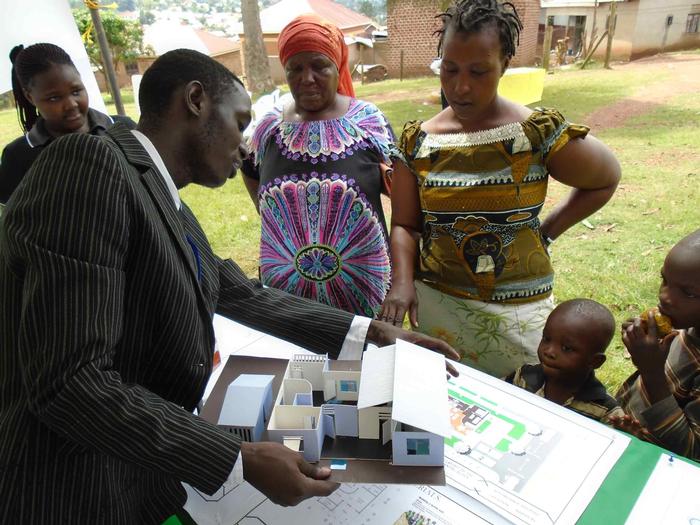

In developing the hub's design, it is instrumental for the architects to step down from their role as authoritative designer and become “humble listeners”. The design process should start with inviting the city's teenagers to provide suggestions about the hub's spatial programme and how it should feel. The current design of schools in the Maldives is a perfect example of the disastrous results that arise when adults monopolise the design process. They operate under the arrogant assumption that they know what the students need, but ultimately overlook the needs of the students. Rather than spaces that encourage learning, leadership and collaboration, it reinforces tyrannical hierarchical relationships between teachers and students. The process for designing the hub should be the antithesis of this authoritarian approach, encouraging designers and teenagers to collaborate as equals.

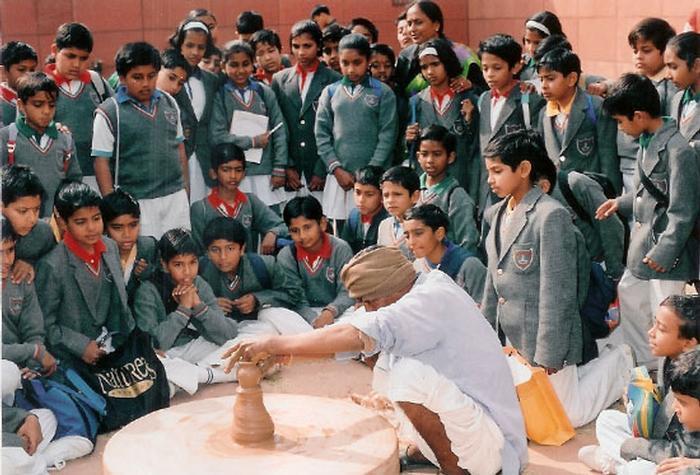

Furthermore, the Maldivian society tends to focus wholly on traditional academic pursuits. Therefore, the youth hub could concentrate on the non-academic interests of teenagers frequently dismissed within this culture of academic meritocracy. Studios for wood-working or music could be part of the hub alongside gathering spaces for socialising and forums. Much like the studio tutorials at the University of Berkeley where design consultants who are disabled consult students throughout the design, the architects and designers of the project should continuously consult the youth as there is no other way to understand their needs comprehensively. Finally, during the construction and refurbishment of the building, teens can volunteer to help. The construction should be an insightful experience for the volunteers, similar to the process of creation at the HelloWood summer school4. By involving them in the construction process, they would feel as though the finished space belongs to them. It also gives the teenagers a chance to hold social responsibility which will aid them on their journey to adulthood.

Step 3: Public Programme

Once the hub is constructed, youth volunteers will lead the initiative with the help of adult mentors. The centre will run similarly to the recent project, Mansions of the Future, in the UK5. This community centre ran a public programme alongside what they labelled the take-over programme. The public programme will be curated by the NGO’s youth volunteers, holding events such as film screenings and talks. These events could lead to discussions where teenagers can voice their opinions in a safe space, either in a group or privately with a mentor or counsellor, creating a dialogue on issues that the traditional Maldivian society considers taboo such as sexual education. Additionally, free after-school activities, such as music lessons, could be offered for adolescents, encouraging them to pursue non-academic hobbies. Communal lunches and exhibitions will engage with a broader portion of the community and help integrate teenagers into the city's urban fabric.

Step 4: Takeover Programme

Alongside this public programme, the hub will launch the take-over programme. This allows teenagers to book spaces in the building for their needs; for instance, using a meeting room to organise a book-club gathering. They are able to define and take ownership of the space, improving their leadership and independence. It democratises the available resources and shares the value of what was created. Through an inclusive design and utilisation process for the building, the proposed solution ensures that these silenced voices are always heard.

Phase 2

The Faces of the Other Atolls

The scattered nature of the Maldivian geography makes developing infrastructure and supplying resources to each island a near-impossible task. Continuously pushed aside for development, the face seen by the youth of these islands is that of an impossible choice. Either they must leave their islands and often their family and move to the overcrowded capital to pursue even a high school education or stay on the island where opportunities and resources are significantly less. The move to Male' is often fraught with experiences of discrimination, deepening the divide between those from the capital and other islands. The government's centralisation approach perpetuates the toxic cycle, aggravating many of the issues previously mentioned. Hence, it seemed unfair and against the 'right to the city' to neglect the youth in other atolls when devising the solution.

Step 5: Assemble

The second phase ensures that the initiative addresses the issues highlighted above and provides a solution for all islands. After establishing the community hub in Male’, the organisation will run a volunteer programme open to older teenagers. The volunteers will be grouped into teams with mentors, volunteer architects and other professional volunteers such as counsellors, psychiatrists and lawyers. An interdisciplinary team such as this is crucial in tackling the vast array of problems the youth face. For instance, lawyers specialising in family law can run workshops on teen abuse awareness and taking action against perpetrators. In contrast, mental-health professionals can help address the psychological needs of victims.

Step 6: Voyage

Once the teams are assembled, they will voyage to the other atolls by utilizing traditional Maldivian boats. For Maldivians, these large boats were the means to combat the unforgiving geography of the nation. They represent a lost form of vernacular architecture. By using them for a youth empowerment initiative, this tradition is reborn for future generations. Architects and traditional boat-makers should collaborate to retrofit existing boats in a manner that reflects the past yet serves the needs of the volunteers in efficient ways. They must ensure that there is sufficient accommodation for the volunteers and additional spaces for communal activities. The boats help transcend the bounds of a brick-and-mortar architectural solution, becoming a vessel for change.

Step 7: Destination

Once the boats reach an atoll, they will first dock at the island housing the atoll council. Here, the vessels transform into a communal space, carrying out a public programme similar to the community hub in Malé. This establishes an initial connection with the close-knit island community through the use of a temporary space, before the development of the youth sanctuary on the island. The boat becomes where the youth can hold discussions, voice their concerns and socialise. Taking inspiration from the floating women's arts centre by MUF architecture, the boat's communal spaces will intentionally not be big enough6. This forces the activities and events to spill out onto the island, engaging with more of the community. This ensures that a variety of age groups engage with the programme, raising awareness and gaining support amongst adults as well.

Step 8: Build

The events held at the boat act as a starting point for discussing the youth sanctuary to be constructed on the island. The architects should once again become “humble listeners”. With the aid of the atoll council and teenagers, the architects should identify an existing building or an under-utilised piece of land on the island to be developed. Additionally, speaking with elders on the island who have a working knowledge of vernacular architecture could inspire new and innovative ways to utilise traditional materials such as coconut thatch and fibres in construction. This would create a dialogue between the elderly and the youth and pass down traditional knowledge of local resources while lowering the building's carbon footprint. Weaving these stories into the construction through communal participation instils social value and personal meaning into the space. Architects who are leading the project will stay on the island until the construction is complete. However, the boat and other volunteers will leave after 3-4 weeks to voyage to a different island. Although the design process remains the same throughout, the outcome differs drastically depending on the needs and suggestions of the island’s youth community. Once the hub is constructed, it will run locally curated public programmes alongside take-over programmes.

Step 9: Growth

Meanwhile, the boats will rotate between islands, providing the community with seasonal activities and events that invigorates the initiative. Through this rotation, the organisation will gain more youth volunteers, creating a self-sustaining growth cycle. It is also instrumental in forging relationships between adolescents from various islands, overcoming the social schism between capital and island dwellers. This creates the possibility of a future where discrimination amongst Maldivians is less prevalent.

Evaluating the programme through a socio-economic lens, the programme sows the seeds of economic change that will benefit the country in the long run. For small developing countries such as the Maldives that lack natural resources, a robust tertiary sector with a skilled labour force creates the cornerstone for economic prosperity. Improvements in the occupational and geographical mobility of labour will have exponential and long-lasting economic benefits. The programme helps decentralise the economy through the voyages and the hubs and provides essential resources for the youth in all atolls, improving the mobility of labour. Thus, despite the initial investment required for the project, the benefits of developing human capital brought forth by the initiative are enough to provide an economic justification.

Conclusion

As adults, it's easy for us to forget and dismiss the troubles and woes of our teenage years. However, by ignoring their concerns and excluding them from our islands' urban fabric, we are condemning them to a neglected future of murky waters and vice. Rather than creating spaces that try to control adolescents, we should be creating spaces through collaboration and engagement that fosters their development. The youth 'sanctuaries' created all over the Maldives through this initiative aims to provide the youth with such spaces to secure a bright future for the “zuvaan” community; to not leave them with a neglected future.

1. Darwish, M., 2010. To a Young Poet. Poetry Magazine [Online]. Available from: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/53382/to-a-young-poet-56d2329f54d2b

2. Harvey, D., 2008. The right to the city. New Left review, (53), p.23.

3. https://assemblestudio.co.uk/projects/granby-winter-gardens

4. https://hellowood.eu/education/

5. https://mansionsofthefuture.org/

6. https://www.dezeen.com/2016/03/08/idle-women-muf-floating-arts-centre-contemporary-art-narrowboat/

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |