2011 Introductory Essay by Daves RossellDaves Rossell teaches architectural history at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, Georgia, U.S.A. His department is hosting the 7th Savannah Symposium on The Spirituality of Place, February 17-19, 2011. See http://www2.scad.edu/architectural-history/symposium/2011/ Josef Olbrich hoped "to erect a temple of art which would offer the art-lover a quiet, elegant place of refuge." [1] So began the construction of an icon of early modern architecture, ver sacrum, the sacred spring, the Secession Exhibition Building of 1897-98 in Vienna, Austria. The ancient Greek poet Pindar called the Altar to the Twelve Gods erected in the Athenian Agora in 522 B.C.E., “the omphalos (navel) of the city, much trodden, fragrant with incense.” [2] It was a simple enclosure of posts and panels among many grander structures, but it served as a place of asylum for refugees and the point from which all distances from Athens were measured. UNESCO lists over nine hundred sites around the world as having outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of humanity, holding them sacred to world heritage. But whereas some sacredness can be universally acclaimed for all peoples and all times, other sacred places are more particular and unique and special to one or a few. It’s likely that the place that is special to you--that you can be calm in, that you go to in times of stress is probably not on the World Heritage list, but addresses similar fundamental needs.

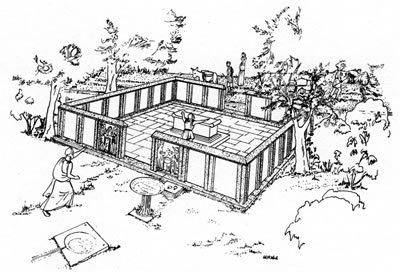

Altar to the Twelve Gods erected in the Athenian Agora in 522 B.C.E

The need for someplace sacred is so clear. There are so many irritations and plights in life. First come the buzz of the fly, the rattle of the dryer, the distant clink, clink, clink, the dull hum. There are so many headlines in so many magazines. Papers pile up. We are subject to incessant interfacing, constant connectivity. Everyone is texting. What is it that makes us so anxious? Is it the heat? Is it the cold? Is it the draft? Is it the still? Are we dirty and need a place to wash our feet? Are we surrounded by too much cleanliness and need some honest dirt? Life can be so busy and hectic and yet we can be so restrained, and ineffective. Life can be so exciting looking and yet so boring and redundant in actuality. We need something real. There is such a thick multi-layered range of events and actions and yet wherever we go we run into a wall. We need some relief. And life can have such sadness. We need to express our sorrow and pay our respects. How do we disconnect, pull out the plug, put it in neutral, turn off the switch? What inner chord is struck? What trust? What old-fashioned musty quiet smell? Where is it? Who knows about it? Can it be shared? Is it high? Is it low? Is it deep and covered? Is it projecting and exposed? How do the seasons affect it? How the course of the day? Is it night you’re searching for, after most are asleep and stars are out? Is it morning, early morning, before the dawn’s early light? Is it exhaustion, the rubber muscle stupor glow of good exertion sweet sweat, and the promise of rest, rinse, scrub, soak? Or is it the exertion itself—the laps, the cool of the water, or the endless circles of the track? Or can we simply rest and place our body in a weightless effortless way and empty it all? Do we seek nothingness, or do we hope for a cubby hole amidst shelves thick with books? Is it light we want or is it dark? Do we need an opening in the crowdedness or a cover and containment in a vacuous eternity? And are we alone? Do we close our eyes in the front row of a slip pew amid congregants? Do we breathe deep as the incense wafts from a chanting Father? Are we prostrate on rugs, with our feet bared? Are we simply amid nature?

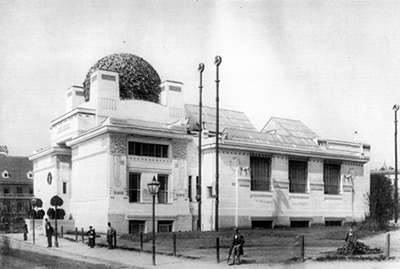

Secession Exhibition Building, Vienna, Austria, 1897-98; Historic Photo;

Consider some possible solutions to salve our wounds: the overnight-cabin on a hike, a floating dock on a lake, a lull in the storm, the café, the covered bench. The recovery place provides solace, community and guidance. The sanctuary is a place where guns are not allowed. The organic farm is a place where one cannot get poisoned. The safety-crossing is a place where one cannot get run over. The school room is a place where one cannot remain ignorant. We close the door to our room. We say these trees cannot be cut. And each of these is equally a point of celebration. Sacred can certainly mean spiritually divine, but it might just mean quiet. The telephone booth used to be a place where one could go and sit and close a folding door and be in a separate space, private and alone. We didn’t have to use the phone. But today we live in a wireless maelstrom inundating us with connection to everything everywhere. According to Matt Richtel who has been writing a series of articles on technology and attention for the The New York Times “In 2008, people consumed three times as much information each day as they did in 1960. And they are constantly shifting their attention. Computer users at work change windows or check e-mail or other programs nearly 37 times an hour.” Richtel quoted Adam Gazzaley, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco, saying “the nonstop interactivity is one of the most significant shifts ever in the human environment.” [3] Quiet is an aural peace, but also a positive sign of inactivity, and thus rest and respite, a time to recharge perhaps, or simply to be in a pure unadulterated way. Sacred usually implies considerable investment of meaning, but it can also just be an undisturbed place. Some boundary separates the outside from the inside. The thick stone walls of a Cistercian monastery like the earthwork ring and ditch that began Stonehenge provided enclosure, reinforcement, edge. As the Japanese architect Tadao Ando has noted, “In my buildings, walls play a dual role, serving both to reject and affirm. By positioning a number of walls at certain intervals, I create openings. Walls are freed from the simple role of closure and given a new objective. They are calculated to accept even as they reject. The amorphous and immaterial elements of wind, sunlight, sky, and landscape are cut out and appropriated by walls which serve as agents of the internal world. These elements are assimilated as aspects of the architectural space. This tense relationship between the inside and the outside is based on the act of cutting (as with a sword), which to the Japanese is not cruel and destructive but is instead sacred; it is a ceremonial act symbolizing a new disclosure. To the Japanese this act has become an end in itself. It provides a spiritual focus both in space and time. In that tense moment, an object loses its definition and its individual and basic character become manifest. Walls ‘cut’ into sky, sunlight, wind, and landscape at every instant, and the architecture reverberates to this continual demonstration of power.” [4] Ando mastered the harshness, abruptness and finality of walls, and was so skilful as to allow the severity to disappear once inside. Separation allowed connection to oneself and nature, in a contemplative relationship.

KOSHINO HOUSE, Osaka, Japan, 1981, Tadao Ando

Of course the essence of a place is the space itself, and a sacred place is divine. The physical structure is something, but it is always secondary to the spirit invoked. Sacred places are sacred in part because their use and meaning transcends the particularities of any architectural detailing present. And that is such a struggle to respect. It is the divine that separates the sacred from the profane. Lao Tzu, the reputed founder of Taoism would have none of it, saying, “Those who would take over the earth But most would agree that sacredness exists on many levels in many places, shaped by humans and not. Tadao Ando the modernist admitted as much when he explained how he has forever tried to design in a traditional Japanese manner, “I prefer to deal not in the actual forms themselves, but in their spirits and emotional contents.” [6] What is the tradition you seek to preserve? How is the space appropriate? Is the actual architecture helping or hindering the expression? [1] Carl E. Schorske, Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1981), 217. [2] R. E. Wycherley, The Stones of Athens (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), 33. [3] Matt Richtel, “Attached to Technology and Paying a Price,” The New York Times 6 June 2010, available online at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/07/technology/07brain.html?ref=technology [4] Tadao Ando, “Introduction,” in Tadao Ando: Buildings, Projects and Writings, ed. Kenneth Frampton (New York: Rizzoli, 1984), 24. [5] Lao Tzu, The Way of Life According to Lao Tzu, translated by Witter Bynner (New York: Capricorn Books, 1962), 43. [6] Tadao Ando, “From Self-Enclosed Modern Architecture Towards Universality,” in Tadao Ando: Buildings, Projects and Writings, ed. Kenneth Frampton (New York: Rizzoli, 1984), 140. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|