|

|

2025 BP COMMITTEE MEMBERS GRANT – ADDITIONAL PROPOSED GRANTS

Benard Acellam

|

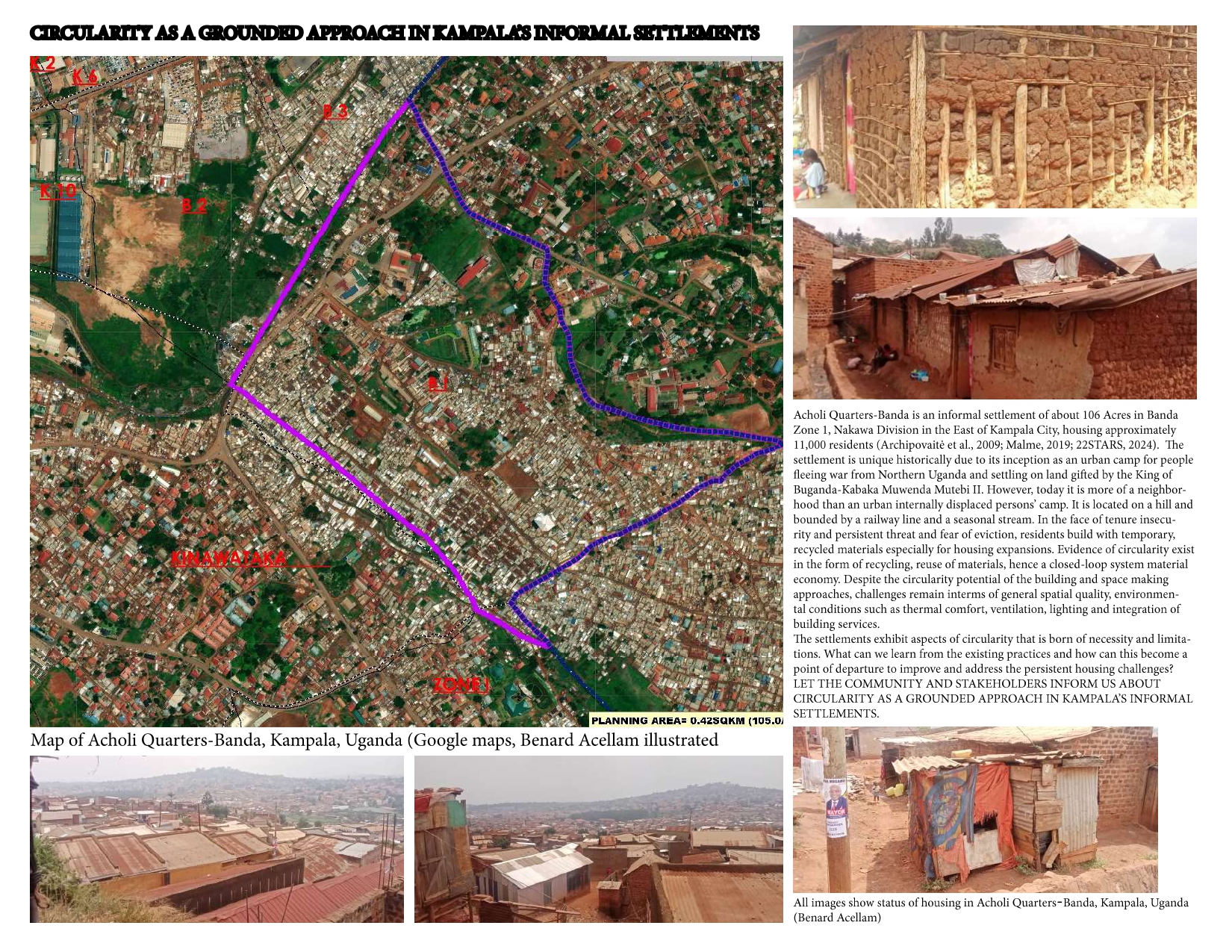

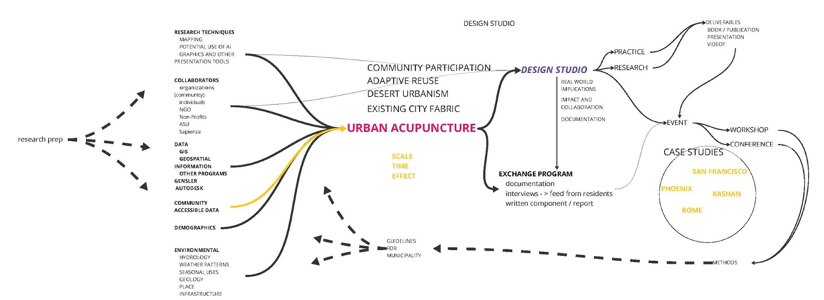

CIRCULARITY AS A GROUNDED APPROACH IN INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN KAMPALA

My application for 2025 Berkeley Prize grant is to support an ongoing academic research project linked to my PhD project but tailored for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Local Learning Studio (LLS) Challenge. The SDGs LLS is a global challenge and resource hub for built environment educators, students, early career professionals and communities, aimed at empowering the next generation of designers, creatives and researchers to realize the UN’s SDGs through local design and research initiatives.

The proposed project will investigate informal housing practices through the lens of circularity. By focusing on the building and neighbourhood scales within informal settlements and capturing diverse voices of stakeholders, it seeks to reveal housing practices that could redefine the concept of circularity in informal settlements. It contributes to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), 13 (Climate Action) and 17 (Partnership for the Goals). Using participatory research and co-production methodologies with the community, it seeks to challenge mainstream understanding of circularity.

An expression of interest has already been accepted for this project in the LLS challenge, and an invitation made to participate in stage 2 submission. For this submission I intend to look at Circularity as a Grounded Approach in Kampala. Using interviews, focus group discussions, systematic sketching and transect walks in the informal settlement of Acholi Quarters, I intend to explore the potential and meaning of circularity for dwellers, local artisans and tradespeople, and professionals such as architects and planners working in informal settlements, and how the meaning of circularity differs from Global North perspectives. I intend to involve 3-5 undergraduate architecture and urban planning students from Makerere University as research assistants.

The project will be disseminated through the LLS Online Gallery, and be showcased at the 13th World Urban Forum in Baku, Azerbaijan in May 2026. Themed “Housing the world: Safe and resilient cities and communities”, the forum aims to shine a global spotlight on the urgent need to address the global housing crisis. The grant request of the full amount of 10,000 USD would support the actual participatory research and data collection within the settlement, stakeholder engagement activities, and facilitate the preparation of the material to be exhibited on the online gallery, which includes posters and a video documentary. Additionally, it would facilitate participation at the World Urban Forum 2026, where LLS Challenge projects would be exhibited physically. It’s also anticipated that this project will contribute an essay for Routledge’s 'SDGs Online' publication (another dissemination outlet for the LLS Challenge) by end of 2026.

Participation in the Forum would be an opportunity to share the lessons from the proposed project to a global audience, to learn and network with likeminded colleagues, adding merit to my doctoral studies. The LLS Challenge builds on the previous works of Global Studio. As an alumnus of the Global Studio, it would be special for me to reconnect physically in Baku with some friends and colleagues from Global Studio Bhopal, 2012.

Link to LLS Challenge: https://locallearningstudio.org/

Informal Housing and Circularity-Status of Acholi Quarters-Banda, Kampala

|

Erick Bernabe

|

(Working) Title

A Pattern Language for Our Children

Overview

I am applying for a grant from the Berkeley Prize Endowment to support my personal research project while on sabbatical in 2026. This project is the first phase in drafting a pattern book for the design of a built environments (from home to city at large) that supports the well-being, safety, and development of children. This phase includes discovery, research, and the development of draft patterns while travelling in Japan and Portugal.

Background

In the US, our system of individualism and meritocracy divides the haves and have-nots. Regarding mental health, physical health, safety, education, and social development, parents believe their child deserves the best. However, under our system that necessarily means another child receives the worst. Furthermore, we believe failure falls on the individual (e.g., the parent, the child) and not the system (e.g., lack of funding, rooted racial inequities, housing insecurity, etc.). This is a moral injury; we know something is wrong, yet we accept it.

What can our spaces — our homes, schools, parks, main streets, civic spaces, etc. — tell us about successful (and inequitable) outcomes for our children?

The intent of A Pattern Language for Our Children is to develop a shared, practical language of patterns that promote a supportive relationship between children and place. During sabbatical I plan to outline the components of the work and share milestones as the project evolves (e.g., Substack stories as patterns are developed, presentation and exhibit after my sabbatical).

Although this project was conceived in the US, researching other countries aligns with my sabbatical plans and presents the opportunity to learn and identify patterns in different contexts. Among the countries listed in UNICEF’s Child Well-Being Report Card (2025), Japan ranked #14 among the 43 countries listed and is already part of my sabbatical itinerary. The addition of Portugal, ranked #3, will diversify my research.

Student involvement and opportunities

I see future opportunities for this work in architecture studio courses at the undergraduate level and believe there are interdisciplinary opportunities with schools of sociology and childhood development.

Funding

My sabbatical is self-funded, spanning several countries, and primarily for reflection at mid-career. I estimate that this $10,000 grant will help fund the following:

- A portion of the travel and accommodation costs for Japan and Portugal

- Time and material costs associated for design, drafting,, and printing for the project

- Supplemental materials to be determined as the project evolves (e.g., Substack subscription and development of stories at milestones)

Timeline and projected completion to date

Project preparation begins January 2026, with the bulk of the discovery and research work occurring in spring and summer 2026 on location in Japan and Portugal. Progress milestones include 2-4 Substack stories to provide overview of the project, the process, and insights from visits to Japan and Portugal. I’d like to exhibit this work after sabbatical (location and format TBD).

Thank you for your consideration,

Erick Bernabe

www.linkedin.com/in/erick-bernabe

Preschool children in Japan socializing in a natural play environment.

|

Aleksis Bertoni

|

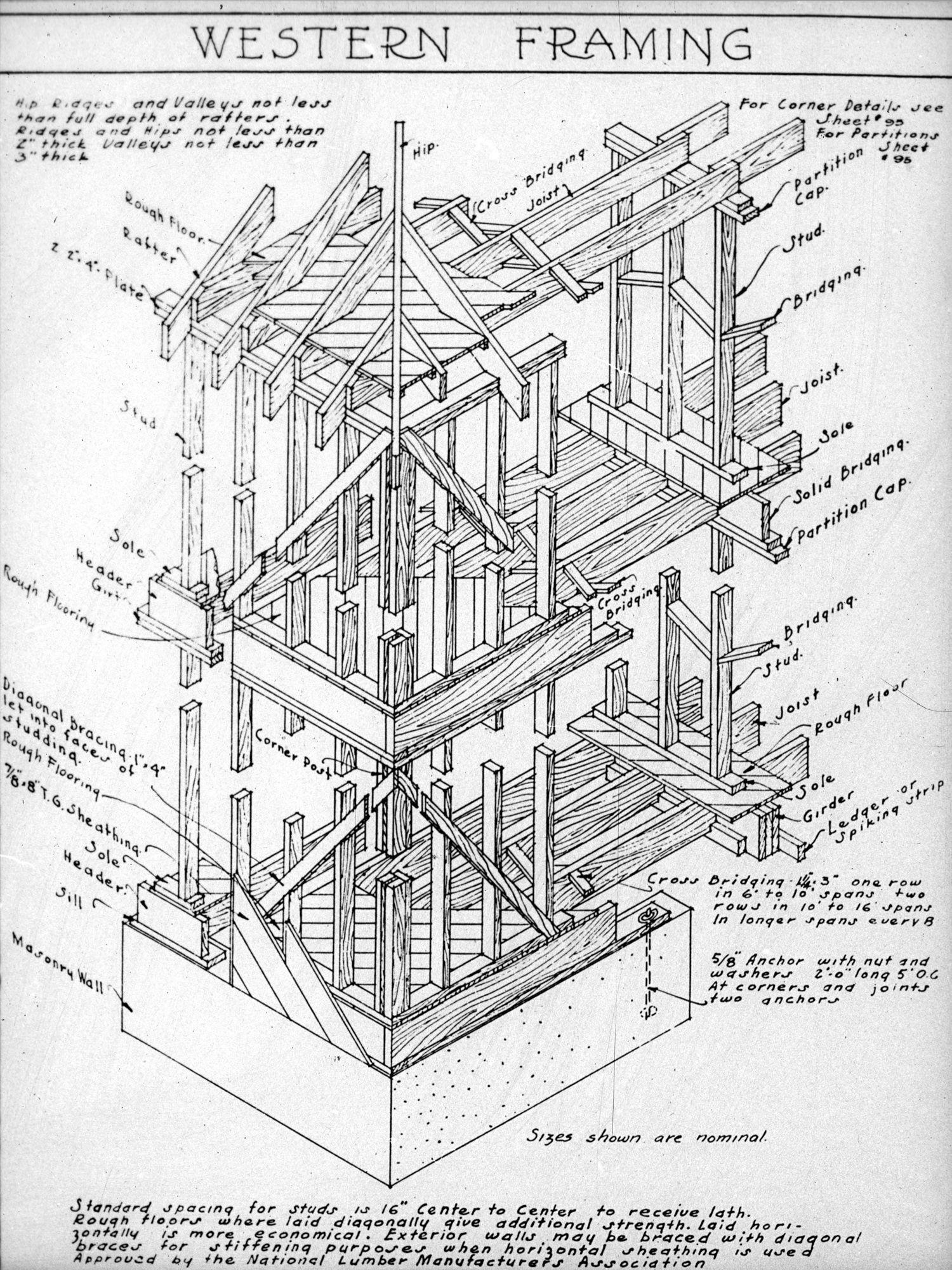

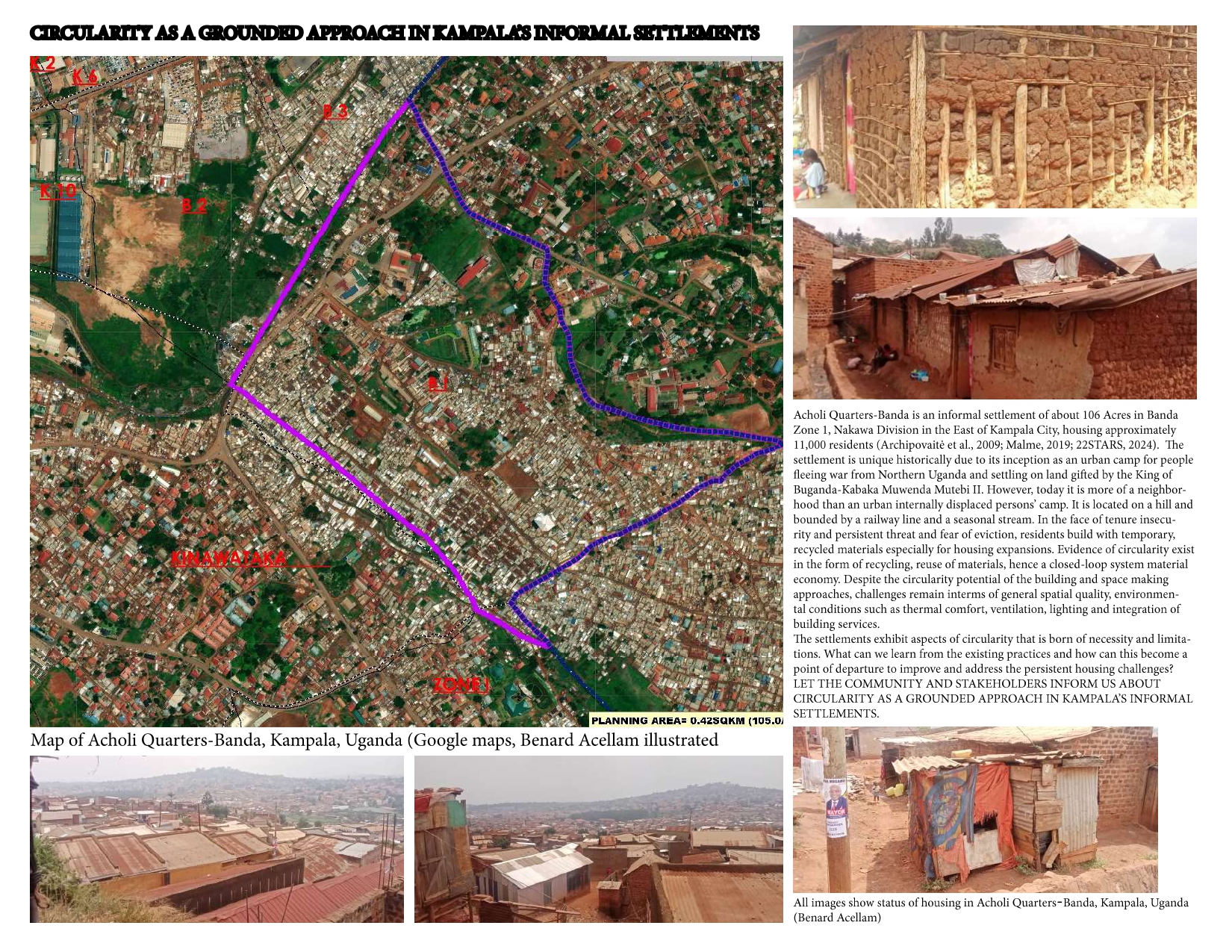

Framing California

Overview

I am applying for this grant from the Berkeley Prize endowment to fund a collaborative research and teaching project between my architectural practice Type Five, and an undergraduate option studio course in the UC Berkeley Department of Architecture. The project centers on residential light-frame wood construction and its associated design culture, with particular attention to the labor, resource management, and logistical systems that undergird this ubiquitous building method in California.

The shared territory between my practice and the proposed studio lies in a close engagement with wood framing as both a technical system and a social infrastructure—one shaped by labor relations, forestry practices, regulatory frameworks, and economic pressures. The grant would facilitate the students direct engagement with these often-obscured forces through collaboration with local tradespeople and one-to-one construction prototyping.

Background

Type Five (typefive.com) takes its name from Type V construction, the International Code Council’s designation for buildings constructed primarily with dimensional softwood lumber. As a design/build firm that specializes in optimizing wood framing, we encounter on a daily basis the cultural, political, and economic conditions that shape California’s built environment but rarely enter architectural discourse. Over five years of practice, we have identified a convergence of forces—housing policy, labor availability, material supply chains, and construction norms—that collectively give shape to wood construction in our current context.

This work carries particular social urgency. California continues to face a severe housing crisis: the majority of renters and nearly half of homeowners are cost-burdened, and the state’s unhoused population has grown by more than 20% in the past five years. Estimates indicate a statewide housing shortfall of three to four million units. More than 90 percent of California’s housing stock is built with softwood framing. As the state seeks to expand housing production at scale through legislation and economic incentives, wood will remain the primary material through which housing is constructed. Understanding how, by whom, and under what conditions this raw material is transformed into housing is therefore both an architectural and political imperative.

Student Involvement and Pedagogical Framework

My partner at Type Five, Ian Miley, is a member of the faculty in UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design and will teach an undergraduate senior architecture studio in the 2026 Spring semester. This studio will focus on two interrelated themes that are central to our practice; the development of new housing typologies in response to contemporary social and economic conditions, and the critical exploration of softwood framing as a widely available yet under-examined construction system.

The Berkeley Prize grant would support direct collaboration between architecture students and local framing professionals. Students would work alongside tradespeople to produce full-scale wood-framed mockups, using construction as a research method to simultaneously instruct and interrogate normative techniques. This would instigate a line of inquiry into the contemporary Californian lumber industry and the overlooked workers whose expertise and labor are instrumental to the realization and maintenance of our built environment. This grant would make possible the fair compensation of tradespeople for their sustained participation, enabling an ethical and reciprocal exchange between students and craftspeople.

The result of this collaboration would include a body of full-scale construction prototypes, along with a publication featuring photographs and analytical drawings that document the research and its geographical, material, and pedagogical implications

Project Completion Date

The studio will conclude on May 15, 2026. Remaining grant funds will be used to employ one or two students to finalize a studio publication, which will be completed and prepared for print and web distribution by August 15, 2026

American soft wood framing diagram, a universal kit of parts that is fundamental to American home architecture and construction.

|

Dorit Fromm

|

In architecture, design for social connection within housing is acknowledged and encouraged but there is less understanding of the social changes that occur over time. This is especially concerning in collaborative housing,[1] whose social fabric is a crucial aspect of housing design and function.

I am interested in looking at community agency— groups collaborating and adapting to address change (that would be difficult to overcome individually). In community-led housing, residents have agency to organize, design and manage their housing community. The social glue of relationships, shared values, and participation had worked to realize a housing development, but how is it working over the decades?

What happens when community agency is stuck (defies adaptation). When the original residents move on or reduce their leadership roles as they age, when an unexpected economic event or a pandemic occurs, when the common spaces are used infrequently, when residents participate less--how do communities adapt and move forward? Are there consequent design requirements?

I would like to request a grant to provide 3 communities with a specific amount of funds; seed money to be used within 6 months by a group of residents (Resident Group) to improve its adaptability--defined by the community as a project that improves agency to handle existing or upcoming changes.

I have maintained connections, visited, and been involved in the three communities listed below, and have published about two of them. Each was built 45 + years ago (with intentions of creating socially connected housing); residents have demonstrated agency and initiative; each has adapted over the decades and has faced hardships. Two continue to function as a community. In observing a group of residents working to improve their community’s adaptability, I will look at metrics of speed of consensus, competence of completion, community satisfaction, and if the solution continues over time.

-Wandelmeent (Hilversum, The Netherlands 1977), a low-income public cohousing development. Resident participation is reduced; aging of founders; common kitchens used less (one repurposed for refugees). One cluster houses students, who would be invited to participate.

-El Sitio (Mexicali Experiment, Mexico 1976) was built by UCB and Mexicali students with local families under the direction of Christopher Alexander. The shared courtyard has been divided among the residents and privatized. The common community buildings next to the homes have recently been taken over by the Architecture Department, University de Baja California (UABC) as a teaching space. Would it be possible to introduce a new aspect of social interaction to benefit the surrounding neighborhood? INSITE Arts (San Diego) and UABC bring students to the site who would be involved.

- Findhorn (Forres, Scotland 1962-72) recently celebrated its 63rd anniversary. Due partly to COVID, they are moving towards resurrection of their educational program which couldn’t maintain financial viability; increasing entrepreneurship a new direction.

Budget

$6,000: $2000 each for 3 community agency experiments

$1,600: Photographic reproduction/publishing rights, editing, preparation for academic paper or article.

$2,400: Partially offset my travel costs--$800 per community.

[1] Housing formed and led by residents to emphasize community.

Wandelmeent residents have initiated changes to their shared (public) pedestrian street and use of some common rooms.

|

Alex Gonzalez

|

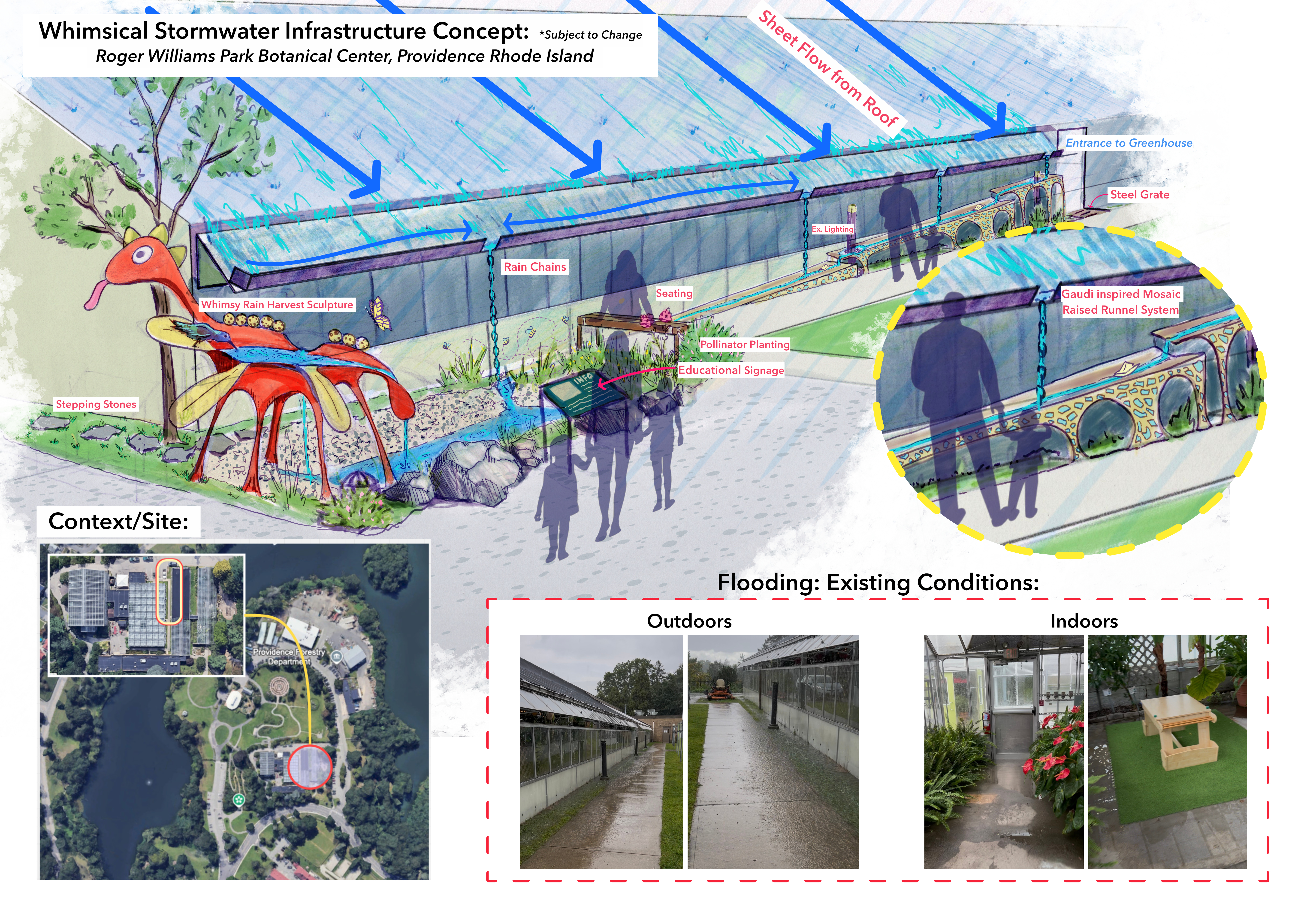

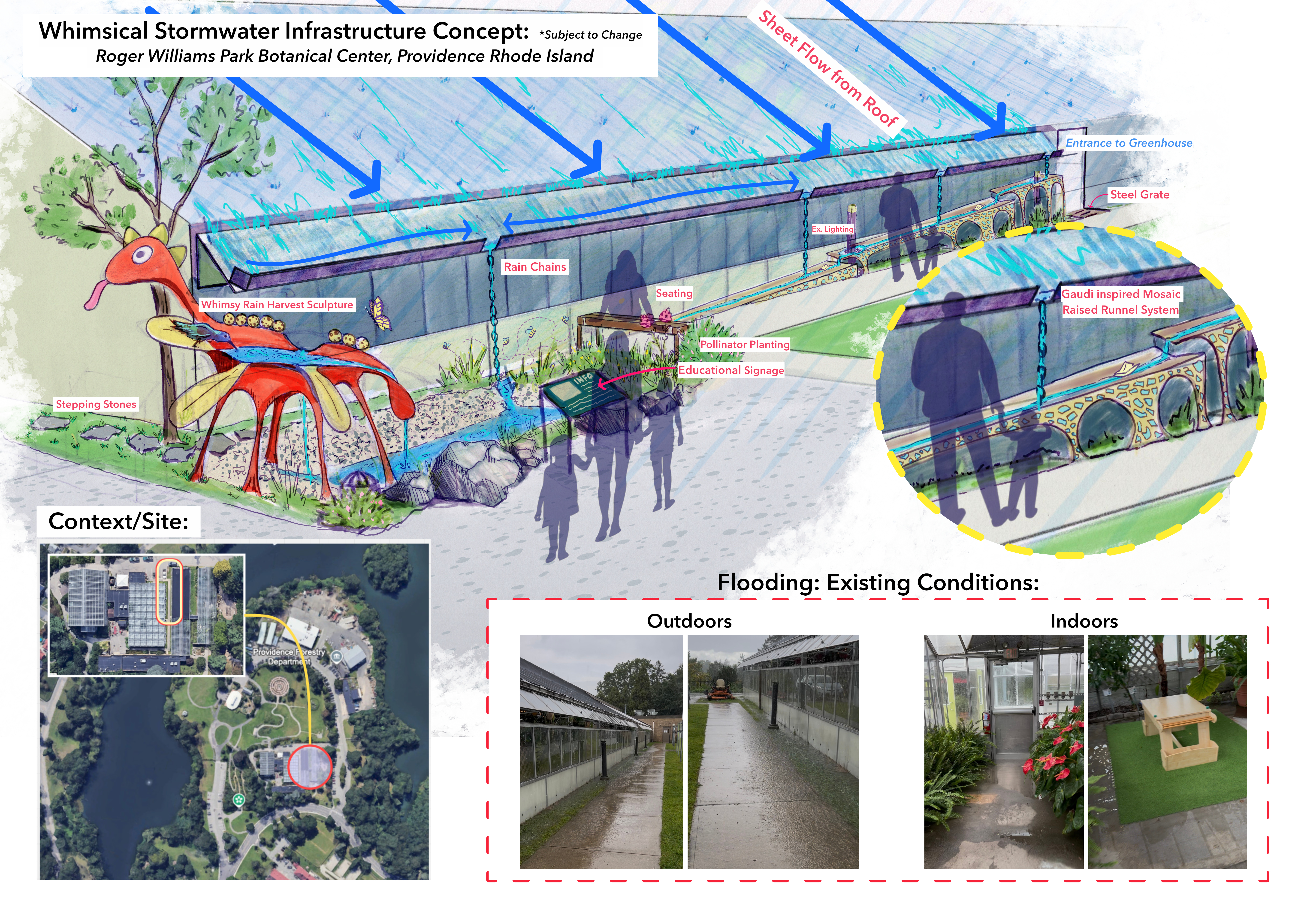

I am seeking the Berkeley Prize grant to fund the artistic design research, development, and implementation of a sculptural work of stormwater infrastructure at the Roger Williams Park Botanical Center. This project addresses serious, persistent flooding issues along a central outdoor corridor and elevates otherwise inconspicuous infrastructure into a vibrant educational space.

I have advocated for the city’s investment in this proposal for over 8 months and initiated the design process. Through this, I have garnered support from leadership at the City of Providence Parks Department and non-profit collaborators.

We are currently in early design stages as we explore ideas, while assessing budget and feasibility. Although the design has not been finalized, the direction I am exploring takes inspiration from the organic architecture and colorful mosaics of Gaudi’s Barcelona. As a public entity, however, there is not substantial funding available to elevate the project beyond practicality and into my vision for a work of infrastructural art. This, I view as a missed opportunity to not only address an existing flooding issue, but also educate and inspire visitors to reflect on our individual as well as collective relationship to the ecological forces of water.

As the current Volunteer Coordinator of the Botanical Center, and a practicing mixed-media artist with a strong design background, I am in a unique position to coalesce involvement in my community and plant seeds towards a sustainable vision for Providence that leverages its status as “The Creative Capital” in the “The Ocean State” to create art centered around water infrastructure.

Collaborators:

In its current state, the project will involve the City of Providence Parks Department, R.I. Audubon Society’s Stormwater Innovation Center, union crews, volunteers, and young adults in construction trade apprenticeships.

It seeks to invite those who shape our cities to think differently about how we approach infrastructure as well as educate on the function, importance, and beauty of the hydrological cycle.

Once the design has been finalized, I will put out a call for student volunteers from RISD’s fine arts and design departments to assist with creating the organic forms and mosaics along the stormwater channel and rain garden.

Funding:

The Providence Parks Department will cover planting, materials, and some labor, with additional labor provided by the nonprofit Building Futures RI.

These existing sources of funding, however, will not cover the additional time, research, materials/tools, facility access, design, and, finally, implementation of a more artful approach. Therefore, without financial support it would require an extreme amount of time, money, and energy on my end that I do not have the capacity for as a part-time employee at the Center. The grant would make it possible for me to dedicate myself full-time to the project’s creative development and oversee its actualization as it will relieve me from the additional burden of independently financing it. Therefore, I am seeking the full $10,000 or as much as the committee is able to offer.

|

Neelakshi Joshi

|

Cultivating social cohesion in polarized times: the role of intercultural community gardens in Dresden, Germany

Overview

This project studies intercultural community gardens as vital urban infrastructure for fostering social cohesion in times of growing polarization in Dresden, Germany. The grant funds two undergraduate internships to study how gardens facilitate meaningful contact between locals and immigrants, countering prejudice. Support will enable rigorous data collection, academic writing and dissemination.

Background and Previous Research

Urban community gardens are plots of land, managed by residents, to grow fruits and vegetables. Beyond their ecological function, community gardens play a critical social role in bringing diverse groups of people together. This contact builds social resilience, particularly in times of crises. During the COVID-19 pandemic I conducted ethnographic research in community gardens, studying their vital role in connecting people1. Gardens became safe, open spaces where individuals could not only grow food but also engage with others, combatting the alienation and stress exacerbated by the pandemic2.

Ongoing Research

Observing a growing anti-immigrant sentiment in Dresden, the city where I live, I started a personal research project in 2025 at the intercultural community garden in Johanstadt, Dresden. Intercultural gardens are socio-ecological projects that aim to bring locals and immigrant in contact. Combining Gordon Allport’s Contact Hypothesis and the role of community gardening in building socio-ecological resilience, I am studying how gardens can serve as point of intergroup contact in Dresden to challenge and overcome social prejudices.

Undergraduate Student Involvement

The grant will support to widen this ongoing research by financing two, four month long, undergraduate internships in summer 2026 (July-October). Students, from the faculty of Landscape Architecture at the Technical University of Dresden, will work in the intercultural community gardens in the neighbourhood of Gorbitz and Prohlis in Dresden. These gardens are located in economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods with a high immigrant population.

Research Plan

Preparation (July): I will provide an overview of the project and share my methods, findings and experiences from the initial research and introduce students to the garden coordinators.

Data collection (Aug.-Sept.): Students will work in the gardens and write ethnographic diaries as well as conduct interviews with gardeners.

Community feedback (Oct.): Students will collaboratively present a short video summarizing their findings and collect a round of feedback from the gardeners.

Writing and publishing (June 2026): I will conduct thematic analysis on the textual, audio and video data from the gardens and prepare and submit a research article by December 2026. The students will be co-authors in the paper. The paper will be published by June 2027.

Budget

Two undergraduate students employed @EUR 765/month for four months = EUR 6120

Hospitality costs for feedback workshop = EUR 200

MaxQDA license (one year) for qualitative data analysis = EUR 250

Open access publication fee = EUR 2000

Total = EUR 8570 ≈ USD 10000 (current exchange rates)

Ethics

The project follows ethical protocols for informed consent and data protection guidelines as laid down by the Leibniz Association for Good Scientific Practice.

References

-

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104418 -

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128206

Impressions from the event "Cooking Connects" from the Instagaram page of International Community Garden in Johanstadt, Dresden (Source: Anke Hennig)

|

Thomas-Bernard Kenniff

As a past Berkeley Prize winner (2002), committee member and now Director of the School of Design, University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), I am applying for a Berkeley Prize Grant in order to set up a graduate studies entrance scholarship for research in architecture and social engagement. Founded 50 years ago, the UQAM School of Design’s mission is rooted in engagement with communities, social and environmental justice, accessibility to higher education and shaping better lives for people through the built environment.

Our undergraduate degree in environmental design combines object, architectural and urban design in a holistic approach to contemporary social issues. Our school and its approach, of course, owes much to the pioneering vision developed at UC Berkeley. The scholarship I wish to set up is a celebration of this relation, institutionally and specifically with the Berkeley Prize, marking our shared values for design as a social art.

The proposal is to create a scholarship, the “Berkeley Prize Graduate Studies Entrance Scholarship”,* given to a promising undergraduate in environmental design who is planning to continue in our Master of Environmental Design program (MED). The MED is a research-by-design program founded on the same approach as our undergraduate, the same values of social engagement and aiming at situated and purposeful research. The scholarship would be attributed by a jury based on three criteria: 1) the overall quality of the proposal; 2) its social significance; and 3) the student’s academic standing. The jury would be composed of two professors from UQAM and two members of the Berkeley Prize community.

If possible, the overall grant would be split in four so that four 2500 USD (conv. to CAD) scholarships could be given, one each year between 2027 and 2030. Extending the scholarship this way ensures a continued interest and the prolongation of the Prize’s message of the importance and urgency of social engagement in architecture and design. To achieve this, the original grant would be deposited into a fund created with our endowment foundation (Fondation UQAM), a charitable organization that manages all bursaries and scholarships at our university. If necessary, an agreement could be signed between UQAM and the Berkeley Prize / UC Berkeley validating the attribution protocol.

The students graduating from our MED produce research work of the highest standard on diverse presently relevant topics including well-being and care, environmental responsibility, collaborative design, spatial justice, and inclusive public spaces. Our undergraduates considering graduate work require encouragement, especially in realizing their potential for change. This scholarship is a way of echoing the boost the Berkeley Prize gave me as an undergraduate to pursue graduate studies. The path I have followed up to now has been greatly influenced by finding a community of architects, designers and researchers who believed in the social significance of what we do. Thank you for bringing a little bit of this to our community.

* The scholarship would be presented in French as Bourse d’entrée à la maîtrise en design de l’environnement du Prix Berkeley.

Scott Koniecko

|

Overview As President of the Beatrix Farrand Society for the last ten years I have created and conducted symposiums that from a cultural landscape perspective have explored the ideas that have shaped our understanding of the environment and overall, the meaning of place and American identity. Background For example, previous symposiums have individually focused on Frederic Church, William and John Bartram and Alexander Von Humbolt. In brief, Church’s paintings spearheaded the environmental movement and had close ties with the liberal thinking that strongly endorsed abolition. The Bartrams (father and son) while identifying flora across the colonies, developed the country’s first park and offered a window to the American revolution with one a slave owning loyalist and the other a patriot and abolitionist. And without Alexander Von Humbolt’s vast intellectual contributions we wouldn’t know Emerson or Thoreau as we do today. Participants The Symposium is invitational and includes architects and landscape architects and scholars from around the country and is held at Garland Farm in Bar Harbor Maine, Beatrix Farrand’s last home and garden. Funding The symposium has relied on donors including myself. A grant from the Berkeley Prize would significantly offset what is anticipated as a challenging fund-raising year.

|

John Parman

|

Introduction

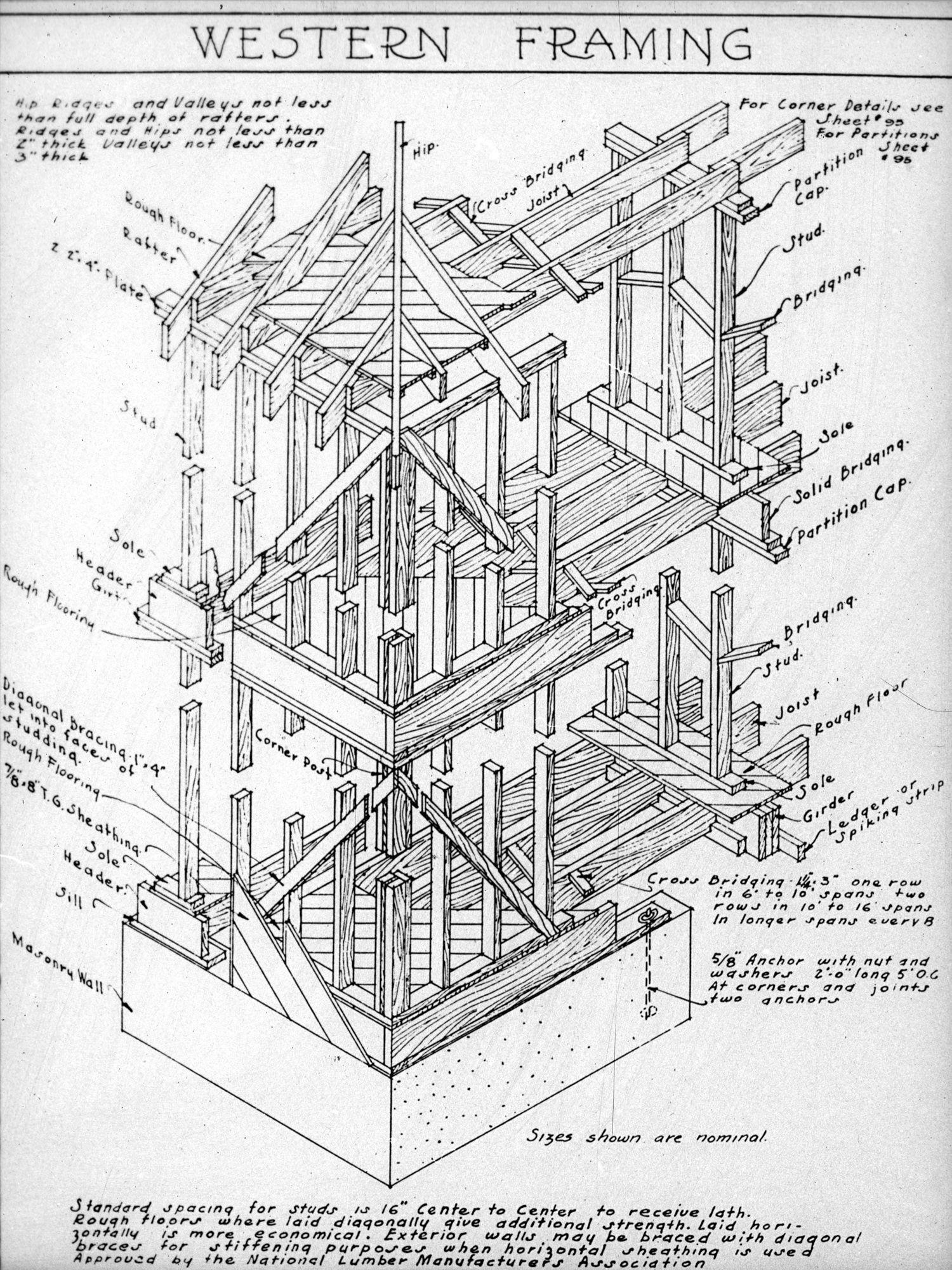

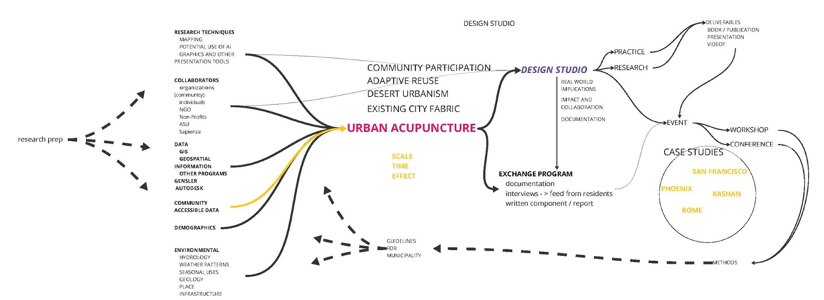

Elham Hassani, Ph.D. (Sapienza University of Rome) and Rockne Hanish, M.Arch. (UC Berkeley) have developed a design studio course that applies AI to resilient urban regeneration. The studio builds on Hassani’s dissertation on the resilient regeneration of Kashan, a traditional Iranian city, applying the methods of the Italian school of urban morphology. Her use of LISP to automate parts of her analysis resulted in a change to those methods. Given her strong interest in making urban morphology actionable in the real world, she studied Jaime Lerner’s Urban Acupuncture approach, which combines urban morphology’s interest in a city’s deeper context and in empowering community participation with tactical urbanism’s focus on strategic urban interventions.

Approach

To introduce the concepts underlying their AI-supported studio, Hassani and Hanish will co-lead an intensive Urban Acupuncture Workshop with 12 architecture-planning students at The Design School at ASU. The school currently offers online, hybrid, and in-person design studios, so having a workshop co-leader teaching virtually from Rome will be entirely familiar to the students. The workshop will apply AI to urban interventions in Phoenix at different scales. We will use AI in three ways.

- As an “archival intelligence”: Students will train AI on place-specific knowledge of their project contexts, both to create a searchable archive that future studios and their students can tap, and potentially to populate a data pond that can be expanded into a city/regional resource useful to practitioners and the community.

- As a “co-intelligence”: Students will use AI applications and tools to support their analysis of site context and conditions; generate and evaluate alternatives; and tap real-time “urban data” pertinent to developing their planning and design strategies. AI will be a teammate.

- As a facilitator of community engagement: Students will use AI to facilitate their interactions with individuals and groups relevant to their team projects. AI support will include identifying respondents, and tracking and summarizing discussions, with the goal of increasing local engagement.

The assigned projects will range from the regional/systemic to the neighborhood scale. Each will be organized so the teams can research the problem, propose and analyze solutions, review them with invited stakeholders and community members (using Ray Lifchez’s Architecture 101 methodology), and present them along with an assessment of the value of AI to each step in their process.

Student Participation and Benefits

Students will conduct the research contributing to a knowledge base for pedagogy, practice, and research. Their understanding of AI will be informed by the focus on resilient urban regeneration in a specific place and climate. They will giv others a resource that AI can help make accessible and extendable. We will also propose a summer ASU-Sapienza workshop in Rome, to apply an AI-enabled Urban Acupuncture approach to that city.

Funding Request

We seek funding of $10,000 to cover Hassani and Hanish’s time preparing and leading the studio, honoraria for up to four guest lecturers, and the direct costs of making AI tools available to the students.

Rocky Hanish’s sketch outline of The Phoenix Studio early in its development.

|

Helaine Kaplan Prentice

|

Eero Saarinen’s Unsung Dorm

While a CED lecturer, I was named a Mellon Fellow for Undergraduate Research to create a capstone class I called “Learning from the Visual Record.” Typically, students rely on written material for history and explanation, with images used as illustration. In this seminar, though, research started with visual material from primary sources, notably our rich Environmental Design Archives. What can be discerned from plans, photographs, sketches, and the site itself, that hasn’t been translated into words, or even noticed, before? Students learned to synthesize image-derived information with textual resources to achieve fresh insights, and returned to their study sites, newly attuned.1

Parallel to teaching this approach, I pursued a research project of my own: the genesis of Eero Saarinen’s Women’s Dorm (1960) at the University of Pennsylvania, known then as Hill Hall. The unexpected drama of its interior volume—open atrium as student commons—is thought to be a precursor to his famed Bell Labs headquarters. Eero Saarinen, esteemed in his time, lionized in ours, saw this building derided by some critics. Having lived there myself at a formative stage, I feel equipped to defend it. The rejoinder resides in the dorm’s success as social architecture.

Grounded in Saarinen’s Finnish roots, this mid-century residence hall was designed to encourage fruitful interaction among peers. Social exchange is plainly expressed in the building’s parti. Can an architectural diagram instigate socially conscious design? In this case, yes––from the moat in!

I’ve visited the dorm itself multiple times, as well as Cranbrook Academy of Art, American home-base for the Saarinen creative clan, and, nearby in Bloomfield Hills, Eero Saarinen’s legacy office.2 But I’ve never made the essential pilgrimage to what I consider the precedent for the dorm’s social architecture.

In part, the grant would allow me to experience the seminal site: Hvitträsk, the Saarinen compound near Helsinki where the family’s vision of communal artistic life originated. Built work itself is a bounteous visual resource––a foundational concept in our Mellon seminar. An investigative visit to the source is essential to declaring that social architecture was a design intention at Hill Hall. More broadly, Finnish architecture would elucidate Saarinen’s unusually artful use of brick, a characteristic material there.

Along with the students, I plied architectural archives, period magazines, scholarly studies; conducted interviews; contacted original photographers 3 and project architects; and visited significant locations. A cache of material was set aside but technology barreled on. Digital files on outmoded hard drives are no longer accessible. Photo library software was discontinued several operating systems ago,4 now requiring a consultant to recover the collection. The grant would support this computer expertise and equipment upgrade. Acquiring a laptop will allow seminar-scale slide talks for undergrads embarking on architectural history research, emphasizing the research process from the Mellon-supported class5 by way of this case study of modernism in dorm form.

My research also revealed that despite the misogyny of the ‘60s, strong female figures play a role in the full story of Hill Hall. And somehow, this outwardly fortress-like building flexed with the arc of change from women’s cloister to co-ed campus housing.

In previous work, I covered the built environment for a broad audience, and while this work may aid Saarinen scholars, the approach will not be strictly academic.6 The thoughtful approach ES used to shape residents’ experience, and the exquisite handling of materials would never have survived the “value engineering” that drives dorm construction today.

Footnotes

1. In collaboration with Waverley Lowell, Curator, EDA

2. In conversation with Ray about this project, he told me about working in that very office!

3. Balthazar Korab (1926-2013) and Richard Gamble Knight (1926-2008)

4. Aperture cannot run on MAC OS beyond Mojave (2013)

5. My rubric for the seminar: Establish, Inquire, Investigate. Analyze, Synthesize, Substantiate.

6. The Penn Gazette, magazine of the University of Pennsylvania, expressed interest in publishing the profile.

A protective brick facade, with sculpted window reveals, conceals a generous, light filled commons inside, and the dorm’s deliberate social architecture.

|

Arijit Sen

|

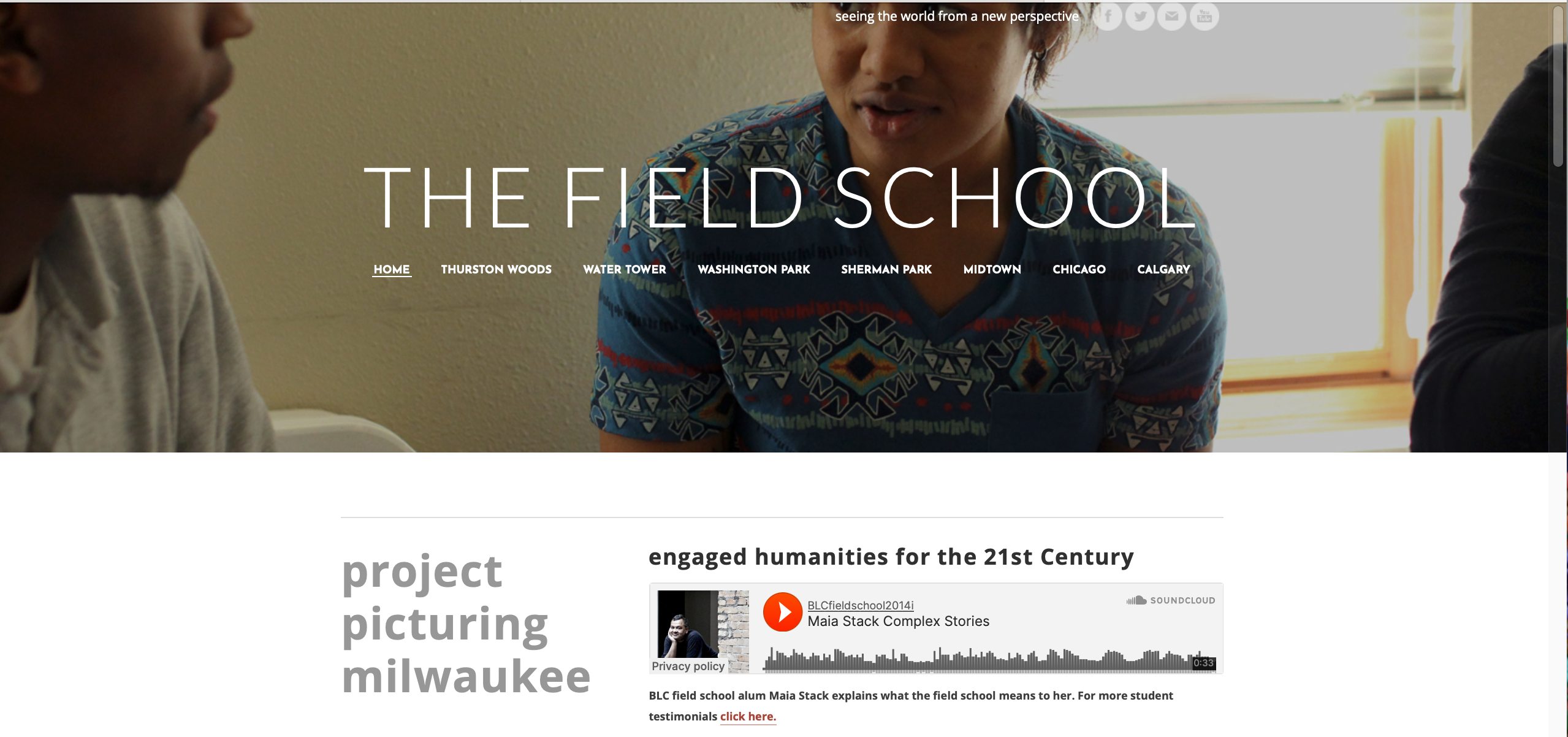

For over a decade, Milwaukee residents and students have documented how everyday architectural practices—from repairing homes to cultivating gardens—help resist disinvestment and sustain community life. This illustrated monograph translates these stories into a resource for neighborhoods and scholars, showing how the social art of architecture fosters care, resilience, and civic engagement.

Accounts of historically marginalized neighborhoods in post-industrial Midwestern cities are often framed through narratives of abandonment, decay, and structural racism—a deficit-based lens that documents harm but obscures the creative, resilient ways residents remake place. For thirteen years, the Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School has worked with more than 90 undergraduate students and hundreds of Milwaukee residents in four adjacent racially minority communities to document their histories. This collaboration has produced 300 oral histories, 100 short interviews, neighborhood maps, over 65 architectural documentations, studies of gardens and landscapes, photographs, design proposals, and field journals. These materials reveal how everyday architectural practices such as, porch sitting, informal repair, community gardening, and mutual aid helps residents reclaim and repair landscapes shaped by disinvestment and segregation while sustaining a rich social life. Several collaboratively produced design proposals will show how architects work alongside communities to build a more equitable world.

The Field School’s methods have been recognized nationally for innovations in public scholarship. In 2022, Wisconsin Humanities adopted these approaches for the Swartz Prize-winning statewide project, Community Powered. The Field School was recognized by Imagining America, the National Humanities Alliance, and the American Association for State and Local History as a model of engaged humanities. These accolades confirm both local impact and national significance in demonstrating how community-engaged design addresses social and spatial inequities.

A Berkeley Prize grant will support the design, editorial, and production work for this illustrated monograph—available in print and as a freely accessible digital publication—translating the Field School archive into a visual and narrative exploration of the transformative power of the social art of architecture.

Designed for two audiences, the book speaks to lay readers and neighborhood residents, offering practical strategies to strengthen their communities, and to students, scholars, and practitioners, who will learn how community-engaged architectural methods confront injustice and disinvestment. Organized around five thematic sections—Porches and Thresholds, Gardens and Commons, Housing Repair and Resourcefulness, Mutual Aid Networks, and Mapping Memory—the book pairs photographs, hand-drawn maps, and archival materials with interpretive essays showing how acts of care operate as reparative community-building. Five chapters written by Field School alumni working globally illustrate how Milwaukee’s methods—oral history, resident-led documentation, participatory mapping, and spatial analysis—have been adapted elsewhere, demonstrating scalability and relevance.

Plan of Work (12 months)

- Curate archival materials, select images, finalize thematic structure, and coordinate alumni contributions.

- Draft essays, edit oral histories, compile maps/diagrams, and conduct community review.

- Hire a student to develop visual identity, create layouts, and prepare high-resolution images for print and digital formats.

- Host community feedback session and present at a national conference.

- Finalize design, secure permissions, prepare print- and digital-ready files, select publisher, and produce initial run.

Building Community, Resisting Injustice: The Social Art of Architecture in Milwaukee’s Northside Neighborhoods

|

Robert Ungar

Background

Students today are hungry for civic engagement, grounded in genuine human relationships that carry design beyond studio walls into the messy, complicated realities of everyday life. This proposal aims to support an already formed community–academy partnership and catalyze its implementation in order to advance the social art of architecture in practice.

Community-Led Initiatives

At Berkeley, students inherit a legacy of engagement with the political and social issues around them, and Oakland offers an equally powerful history of cultural leadership and social-justice activism. Yet many community leaders have grown weary of giving their time and knowledge to academic institutions without seeing tangible benefits for their communities, that shoulder the consequences of structural racism and environmental injustice. This proposal aims to ensure that academic resources support, strengthen, and materially benefit community-led work.

This proposal builds on a long-standing community–academy partnership in West Oakland, grounded in an established network of organizations. Working with David Peters, long-term resident and founder of the West Oakland Cultural Action Network (WOCAN), students helped launch the nationally acclaimed Black Liberation Walking Tour, recipient of the 2025 Oakland Heritage Alliance Award.

Students also contributed to the formation of Oakland Allied Knowledge for Climate Action (OAK), a participatory research collective with WOCAN and the Environmental Democracy Project (EDP), established through the UC-wide CAPECA initiative. OAK advances popular education to strengthen civic engagement in local regulatory processes. Since 2022, OAK had been advancing community awareness around waste inequity in Oakland, and now co-leads community engagement for the EPA- supported Clean Ports program (LINK). This proposal supports the next step: implementation and community benefit.

Student Involvement

Student involvement is anchored in ED 198/298: Civic Imagination Studio, an interdisciplinary elective (LINK) housed in the Master of Urban Design program and open to undergraduate and graduate students across UC Berkeley. Now in its third year, the course follows a five-module structure: Connect, Inquire, Engage, Implement, Reflect, preparing students for community-engaged practice. This grant will support the Implement module for ED 198/298 in 2026, enabling students to translate research and co-design into action.

Students will contribute to two ongoing community-led initiatives: the Clean Ports program and the Waste Equity campaign. Each team will complete a defined implementation task that directly supports current advocacy efforts.

The requested funding enables equitable compensation for community partners and supports the fabrication of prototypes and materials that will live beyond the course, ensuring student work supports community, rather than extracts from it.

Outcomes

Depending on community priorities and co-designed action plans, the following options may be pursued:

Together, these outcomes advance the mission of the Berkeley Prize by demonstrating how architectural education can meaningfully engage with everyday life, support community power, and create lasting social impact.

/ Robert Ungar – Lead for ED 198/298 implementation phase; Berkeley Prize Committee.

/ Yulia Grinkrug - CED instructor, ED 198/298.

OAK: waste equity workshop, September 2025. Instructor, Yulia Grinkrug.

|

|