Samriddhi Khare and Jiya Anand - EssayNew Delhi and the Planning of CarceralityIntroduction

In 2020, while the prison reform movement was gaining traction globally, the architecture student amongst the pair of authors for this essay was met with a "Prison Design Challenge". The brief for the competition eloquently described the requirement for a more humane space for incarceration, one that would focus on rehabilitation over retribution. The organisers constructed their narrative around a prisoner’s dream to someday feel "at home".

But what does that mean for a convict with no home?

In New Delhi, the homelessness crisis is so abhorrent that those incarcerated often dread their release; they would willingly give up their freedom if it meant another day of provisions and a roof over their heads. The words of former inmate Suresh Sharma, "The uncertainty that follows the release of convicts who have served their time in an Indian prison is often more punitive than the sentence." testify that restorative justice without housing equity is a far fetched dream. India's high recidivism rate is invariably linked to its dearth of affordable housing. New Delhi has also been dubbed India's "crime capital", consistently registering the highest crime reports year after year. Indian prisons are hotbeds for caste, gender and class-based marginalisation. We must reconcile these statistics through social factors research and evaluate the prison reform movement through the lens of Indian urbanism.

Behavioural Science

Life sentences make up only 1-2% of convictions in India, so most people entering the system of incarceration will eventually reenter society. However, Indian prisons have no exit systems in place. Post incarceration trauma is often coupled with rejection from one's community. There are no social procedures that allow former inmates to coexist with the community members they have wronged. These vulnerabilities make it imperative that housing design for this community champions inclusion. We believe infrastructure plays a huge role in the social reintegration of former inmates. To counter the current cycle of retribution and criminality, we must broaden our understanding of the built environment, housing policy and behavioural science.

This essay proposes a housing program for the formerly incarcerated that emphasises societal reintegration and minimises the opportunities for future criminal activity to bring about a higher socioeconomic standard of living.

Site

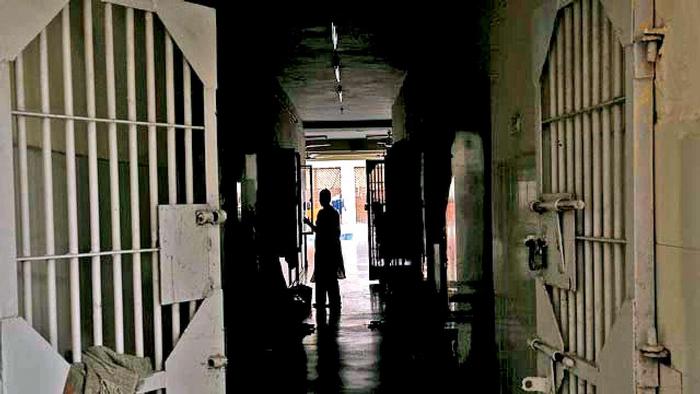

It is impossible to discuss incarceration in India without thinking of the massive Tihar Prison Complex in New Delhi. Despite a sanctioned capacity of 10,026, Tihar was home to 17,534 inmates as of 2018. These numbers have continued to grow at an annual rate of nearly 12%. These massive, centralised camps for incarceration hinder social reintegration post-release. The transition from a large surveillance complex to a home is difficult because the centres are successfully designed to make the inhabitants feel psychologically alienated from the outside world. We must hyper-localise the post-process of restorative justice to facilitate easy reintegration into society. We must think beyond captivity and develop neighbourhoods that are safer for all inhabitants.

The site we propose for a post-incarceration housing project is Uttam Nagar - a district adjacent to the Tihar complex. The neighbourhood is home to multiple unorganised, self-built, colonies with high levels of congestion, inadequate sanitation and poor living conditions. Uttam Nagar also reports the second-highest crime statistics in the city, which translates to a high number of incarcerated people. On-ground analyses reveal that citizens are willing to take on more active roles in their communities if it means a de-escalation in crime levels. The demographics of the site also illustrate high unemployment rates and low literacy levels. Further, being a city centre, Uttam Nagar is well integrated into the existing public transit networks (metro, bus and roads), making the project easily accessible. The proximity to Tihar allows the rehabilitation program to be integrated into the currently existing prison system.

Studying the site through first and second generation Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles highlights many physical and social attributes which may be responsible for the high crime rate and risk in Uttam Nagar. There are no controlled access points/territorial gates, no means of natural surveillance or "eyes on the street", and no sites for congregation or communal activity. The unplanned infrastructure is worsened by the lack of a neighbourhood or community structure. Through this essay, we want to reinforce the notion that physical surroundings are inextricably linked to the social settings in which they function.

Project Team

As stated in the resource article titled "The Built Environment Impacts Our Health and Happiness More Than We Know" by author Jared Green, "The built environment is directly linked with happiness and well-being, and too often urban environments fail to put people at ease."

The mental health vulnerabilities of reformed convicts necessitate the presence of medical professionals on the team, who, in collaboration with architects, can create spaces that feel safe. The program must facilitate a smooth transition from a prison built for surveillance and captivity to an inclusive housing society. Psychologists can curb thoughts and opportunities of criminal activity through behaviour-setting. Altering environmental elements such as building materials, sizes/shapes of social areas, and building orientation based on behavioural concepts such as visibility, privacy and image and milieu can enhance community well being. Through comprehensive individual and group assessments, psychologists can guide architects on designing for former inmates’ welfare.

As social scientists, psychologists can also examine implicit biases and ensure that the hierarchies of oppression based in Indian prisons do not replicate themselves in this design. By forming networks of communication through a mix of elected and appointed community representatives, designers and psychologists can actively prevent Pruitt-Igoe-esque residential exclusion.

Including community representatives in the project team allows thorough democratisation of this design, exemplifying the social art of architecture. The project will be informed by the lived experiences of the formerly incarcerated.

Finally, for this program to be implemented successfully, work needs to be done with the very institutions that have been oppressing former inmates - members of the regional judiciary and law enforcement. They can provide insights about high crime risk sites and behavioural patterns within the neighbourhood. Moreover, working with them gives us the opportunity to sensitise them to alternative modes of justice.

User Integration: Community Engagement

Echoing juror Dorit Fromm, "What if the social connections of the residents came first before the architectural program and built form?"

This program forms at the intersection of psychology, architecture and legalese, so we must develop a design that reinforces these connections while remaining relevant to the context. This can only be achieved through intersectional and interdisciplinary community engagement. As an extension of the diverse professionals involved in the team, users must also be integrated through participatory design exercises.

Due to the language and literacy barriers identified in our study, it is safe to say that conventional modes of engagement such as surveys and mapping can fail while interacting with the former inmates at Uttam Nagar. To overcome this obstacle and incentivise the entire community to participate in the design process, we need to bring humane sciences to the forefront. By collaborating with the team's psychologists, planners can develop innovative and empathetic approaches to community engagement.

An effective way to do this could be through role-playing exercises. By asking citizens to envision themselves as former inmates and vice versa, we could drive change by seeking answers to questions like (1) "What would make you feel safe?", (2) "What would make you feel like this space is yours?/ What would make this space feel yours?" and (3) "Where do you feel most vulnerable?". Similarly, law enforcement and former inmates could be asked to switch places and develop an understanding about the other's expectations from a space or society through introspection and inquisitions like (4) "How would you ensure that the society is safe for everyone?" and (5) "What would you like to use the society's common areas for?"

These questions could also translate into spatial inquiries - with members of each community walking through the colony, describing their experience of the space in terms of safety and potential for design. These exercises, along with repeated community feedback loops, can initiate long term consensus-building attitudes within the community. The program can have a rotating system of community appointed facilitators for the initial 12-18 month phase, followed by a volunteer-based permanent position.

Further questions to be addressed include:

(6) What would you use your home for?

(7) How long do you expect to stay in this home?

(8) How would you prefer to communicate within your community?/How would you like to convey your needs, wants and concerns regarding the society?

(9) What do you like/dislike about your current accommodation?

(10) What is your family size and composition, and do you expect this distribution to change soon?

For a residential society to feel safe, there must be a strong sense of community bonding within the residents. These bonds are often tied to local cultural events and placemaking activities which can also mend the broken relationships caused by the criminal activities of former inmates. These events are often executed by citizens groups or residents welfare associations (RWA). The establishment of an RWA is also integral to assert the occupants' needs, particularly while negotiating with different professionals on the team.

Rural India has been utilising the peacemaking infrastructure of Nyay Panchayats of "public justice courts". Through these Nyaay Panchayats or Gram Nyaayalays, community-based mediations often lead to solutions that uphold the civil liberties of all parties involved. Our cities do not have any such mediums, which is both the cause and the consequence of our lack of infrastructure to support this intervention. With this project, we can realise a similar domestic legal framework for urban India.

User Integration: Design and Build

New Delhi is the third most populous city in the world. Slum clearance and rehabilitation are often coupled with large scale displacements of lower-income residents. Therefore, the only viable route to affordable housing is self-building, or auto-building, through the integration of users on the site. The integrative design process would start with building the former inmates’ capacities for construction. Employing the community would confer a sense of ownership to the builder, thereby making them more likely to take care of those spaces and challenging "offenders' ability to offend with impunity." Working towards a shared goal also helps develop community solidarity. This capacity-building program would ensure stable employment during and beyond the implementation of the housing program.

This auto-building program was executed to partial success in the initial stages of the Indira Awas Yojana (now known as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana). The program stated that the construction of the houses is the sole responsibility of the beneficiary (occupant). The engagement of contractors was strictly prohibited, barring the cases where the beneficiary was physically disabled, where it became the responsibility of government administration to provide full assistance in the construction of the house. However, eliminating the much needed technical expertise meant that the resultant homes were unsustainable and of inferior quality.

Through this essay, we would like to propose a shift from the DIY (do-it-yourself) model to a do-it-together model. With the help of architects and planners, communities that have been designing their own homes for decades can move to an upgraded standard of living by introducing more cost-effective and sustainable building materials, technological innovations and social schematics. Architects can design for the differently-abled and help build homes that are universally accessible. Simultaneously when users share their concerns about the construction, changes can be introduced to the design program. Together, we can ensure that the infrastructure supports the reintegration of former inmates.

Finally, frequent post-occupancy evaluations need to be conducted to ensure that the model is working successfully. Sustaining a cycle of feedback is essential to a housing project which prioritises the clients' needs.

Finance

Acceptance and support from one's community need to follow rehabilitation. Including community-operated employment centres in the design program would generate revenue and develop social cohesion. An effective way to do this is through a public-private partnership. By developing the site in conjunction with commercial developers, reformed inmates have the opportunity to economically sustain this project by adopting employment roles within the district. A cafeteria run by reformed inmates gathered immense success in Shimla, a small city in North India. The site can also incubate ventures like TJ's, Tihar's inmate skill development program, which sells merchandise ranging from food to furniture, all produced by incarcerated persons. The private developers' role would be to finance the commercial district within the society, which would cross-subsidise the future expansion of this project.

However, social responsibility cannot yield to commercial interest. The government could serve as a safeguard against the potential exploitation of the site for commercial gain. To resist the commodification of housing, the onus of implementing the housing component of this project should rest within the public sector. The operation and maintenance should be localised as regional/district authorities have a higher degree of familiarity with former inmates’ concerns when compared to national-level organisations. Local bodies also involve citizen's groups, making residents direct contributors to the community's well being. The project should establish a hierarchical network of accountability within the city, state and nation - with citizen representatives collaborating with professionals at every level.

Conclusion

An empathetic post-incarceration housing development could serve as a ray of hope for the residents of New Delhi and the millions of cities like it in the developing world. Implementing new strategies that work in tandem with citizen governments can build on the intrinsic diversity of Indian cities and communities. This essay intends to highlight the importance of contextual solutions while discussing the marginalisation of formerly incarcerated individuals. We hope to galvanise further professionals from diverse backgrounds who can help further the restorative justice urbanism discourse within Indian and international academic circles.

References

Berkeley Prize Essay Competition. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2022, from https://berkeleyprize.org/competition/essay/2022/essay-question/introduction-dorit-fromm

Crime Capital: Delhi remains most unsafe. (2021, September 16). The Indian Express.

New Research: The Built Environment Impacts Our Health and Happiness More Than We Know. (2021, August 11). ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/964940/new-research-the-built-environment-impacts-our-health-and-happiness-more-than-we-know

parthakhare. (n.d.). Delhi crime. CARTO. Retrieved January 30, 2022, from https://parthakhare.carto.com/tables/delhi_crime_meta/public

Press Information Bureau. (n.d.). Retrieved January 30, 2022, from https://pib.gov.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=0

Sur, A. (2021, November 8). 'Current state of affairs at Tihar shows management is going downhill.' The Hindu.

TEDx Talks. (2016, November 16). Humanising Prisons For a Better World | Niharika Sanyal | TEDxBhilwara. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OgEO1_ORH0g

The International CPTED Association (ICA)—Primer in CPTED - What is CPTED? (n.d.). Retrieved January 30, 2022, from https://www.cpted.net/Primer-in-CPTED

Tihar inmate abuse case: HC tells cops to register FIR against staff. (n.d.). DNA India. Retrieved January 30, 2022, from https://www.dnaindia.com/node/2563797Owen

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|