Philipp Goertz Travel Fellowship ReportJapan, July and August 2019

Exploring traditional earth constructions and digitalization in Japan

"What is it that we really require from the scientist and technologist? We should answer: We need methods and equipment which are – cheap enough so that they are accessible to virtually everyone – suitable for small scale application; and – compatible with man’s need for creativity. Wisdom demands a new orientation of science and technology towards the organic, the gentle, the nonviolent, the elegant and beautiful.” – E.F. Schumacher I start my final report with the very same quote as my travel fellowship proposal. It sums up the agenda and main objectives of my trip to Japan. The first objective was to understand in how far participation in the construction process by its future inhabitants may result in identification with the house and in how far this factor may influence a building’s resilience and sustainability. The second objective was to develop ideas in how far digitalization and computer-aided technologies in combination with low-tech analogue approaches could be beneficial to the idea of participation. And the third objective was to understand the role of traditional clay and adobe constructions and its modern implementation in terms of sustainability and resilience.

First days in Tokyo and the AA visiting school “Ring of Fire” On writing this report my first memory upon my arrival in Tokyo is a feeling of being overwhelmed and a certain uncertainty due to all the very new and never-experienced impressions – cultural as well as architectonical. I remember myself taking the elevator in Kenzo Tange’s “cathedral of modern age” the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building – a building that certainly neither alludes to human scale nor to the above-mentioned ideas of “gentleness, non-violence, or elegant and beautiful”. And after trying to get an idea of Tokyo’s endlessly expanding architecture that only seems to stop where Mount Fuji starts, I remember walking barefoot, on the perfectly maintained, green grass of Shinjuku Gyoen Park. The next memory I have must be three days later during the first days of the AA visiting school at Keio University’s campus. 26 students from all over the world attended this year’s AA visiting school in Tokyo. Divided into smaller groups, we try to find and analyse new materials that could serve as starting point to the construction of emergency shelters for post-catastrophic situations in the so called “Ring of Fire” area. I remember my group trying to weave newspaper but finally coming to a point where we would be convinced that newspapers are limited in length and therefore useless in the approach to constructing a shelter-like structure. At this point Felipe Sepulveda (one of the conductors of the workshop) gives us an inspiring speech on paper and shows us some very simple method on how to connect the newspaper by the absolute simple mean of folding and rolling. This moment somehow has become a very vivid memory to me. I think being exposed to so many new impressions – the sheer size of Kenzo Tange’s administration building and the perfect green grass surrounding a traditional Japanese garden helped to open myself up to Felipes Sepulveda’s and Barabara Barreda’s idea on questioning all common and shared assumptions we might have on architecture, construction and material and to start searching and thinking off the beaten track The main task of the visiting school was to “explore innovative new ways of designing shelter to respond to natural disasters in a 40,000 km area of the Pacific Ocean, known as the Ring of Fire”. The first days of the ten-day workshop were characterized by some inspiring lectures that I will try to sum up in the following paragraphs. The lecture by professor Christoph Kaltenbach focused on a key factor in post-catastrophic environments which I had never heard about before: mental fitness. Enabling human’s capability to react quickly and efficiently in the moment of panic and trauma is crucial to a good design of any construction or shelter that shall respond to natural disaster. Another key factor is the so-called sense of community. More than ever, humans are in absolute need of community confronting trauma and shock in the moment of catastrophe. Ikeda sensei, professor at Keio University, showed us a project conducted in the aftermath of 2011 earthquake in Japan: a cnc-milled wooden construction was delivered in its components to a destroyed village – the individual pieces of the pavilion were then joined together by young elementary and high school students of the city in a joint effort. This shared activity provides distraction and a feeling of community to the students – an idea we wanted to implement in our design for an emergency shelter. A lecture by Kobayashi sensei, professor at Keio University, would stress the above-mentioned mental factor of building and construction. He introduced us to a project called Veneer-house: a system of completely cnc-milled wooden pieces that could be joint together by non-professionals. A building/community hall/house could be constructed without any complicated joinery or sophisticated tools. He illustrated in how far participation in construction could strongly support a building’s resilience and life-span. Only one of his projects built in the Veneer-system suffered from vandalism and misuse. While being constructed with the same materials and techniques as all the other Veneer-system based constructions, the key idea of participation was not implemented. The tea house was completely set up by Kobayashi sensei’s students. Thus, according to the professor, people in the local community lacked affection and willingness to care for the construction. In the above-mentioned examples digital tools and the means of digital fabrication were not introduced to come up with endlessly sophisticated, non-understandable design that could only be turned into a physical being under huge effort of experts and engineers, but as tools that can and should enable us to come up with simple and understandable solutions that could easily been built by non-professionals. Software like Grasshopper and our computers become the enablers of a sense of community. Especially interesting to me was the different view on computer-aided technology and digital fabrication introduced by Ikeda sensei and Kobayashi sensei. Unlike in my previous experience they were not considered to be tools that make obsolete any human labour and creative input but to enable everybody to participate in the process of construction. It became a chiasmus of any previous thought I had on this technology. Kobayashi sensei quoted a befriended professor as follows: “Humans actually enjoy the process of building. Why should be leave the joy and fun to robots?”

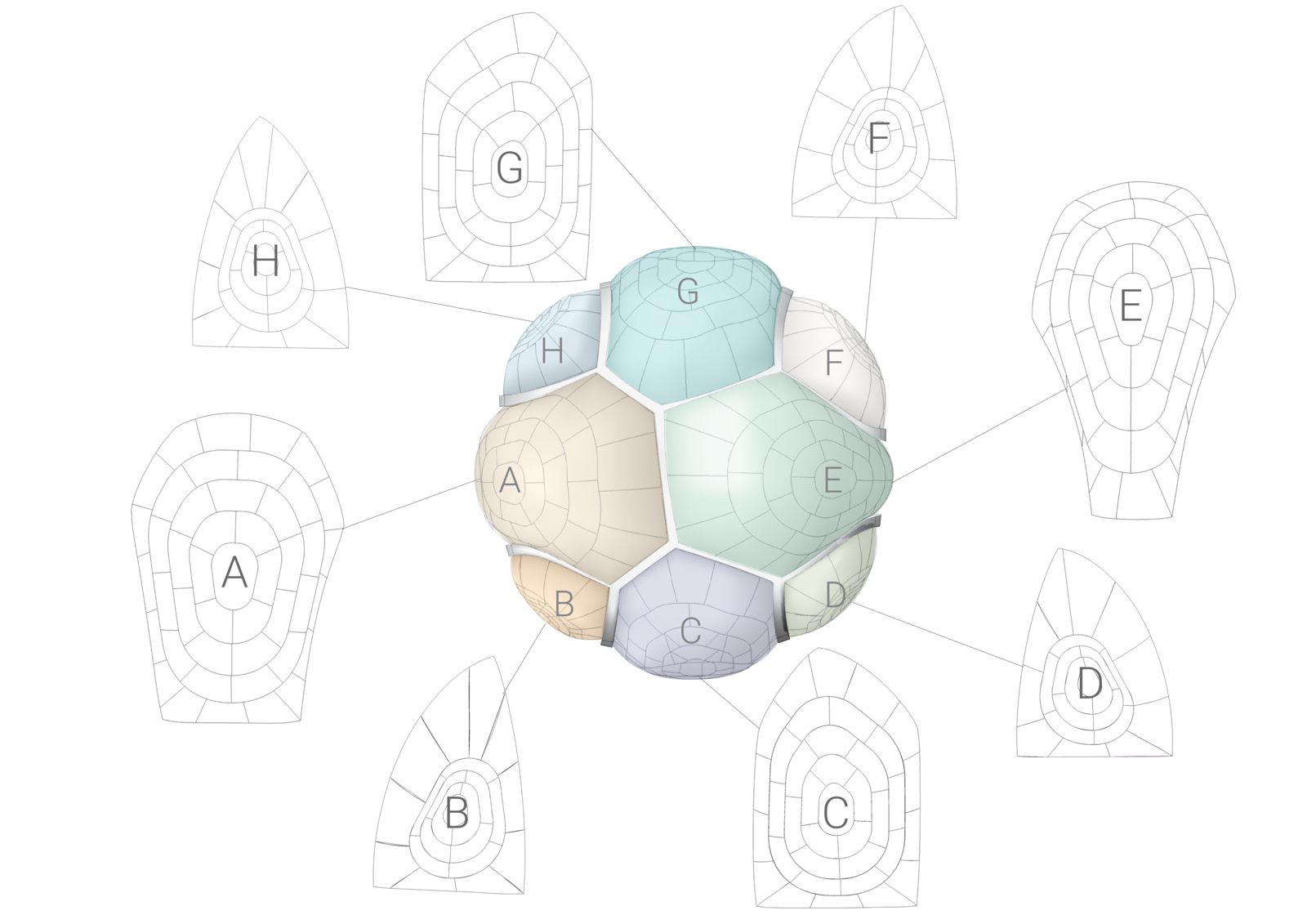

In the following days we developed an inflatable PVC structure consisting of an agglomeration of various bubbles. The very topography of this structure would become a physical blueprint to a shelter made of paper. The moulds at the connection between to bubbles would anticipate beams to the paper shelter. The highs of the bubble would be covered in a thinner layer of paper. While we tested some mock-ups of paper, we understood that it needs to be further investigated in how far the paper is the most suitable material for an emergency shelter. The inflatable PVC blueprint, however, allows for a wide-range of possible material to serve as a porting construction.

Apart from the great joy I had working with these 26 highly motivated and incredibly nice students and some great and inspirational teachers, it is four insights I regard especially important for my future interest in the combination of modern technology and traditional construction techniques in clay and adobe: a) Computer-aided technology and digitalization do not necessarily mean to make obsolete any manual and oftentimes rewarding manual work by humans. b) Computer-aided technology and digitalization, on the opposite, could even be necessary to enable unprofessional workers, in current work and living environments, to be participate in the construction of any kind of architecture. c) Prefabrication and digitalization can highly increase accessibility and scalability according to varying needs. d) A sense of community and ownership due to participation in the physical construction (NOTE: not in some superficial design participation) can strongly increase resilience and endurance of a building and be crucial in empowering humans to deeply enjoy a buildings physical presence.

Tokyo, Kyoto, Kobe and a self-guided trip to some clay walls and thatched roofs In my remaining days in Tokyo after the workshop, I had the chance to meet the Japanese master artisan in clay plastering Tatsuya Tokura. Tokura san took me to several examples of his work – including the interior of a luxury shop within a department store, an apartment, an exterior wall in front of a shop and some tables constructed in clay.

The next day, I joined Tokura san’s co-worker Shigaku Itagaki on a visit to Toyama Memorial Musem. Nestled in rural scenery, the house built by Gen-ichi Toyama for his mother Mii, is a perfectly conserved traditional Japanese house (or villa) completed in 1936. I could witness how architecture can synthesize or enable humans to reach a state of admiration for beauty and peacefulness. Many kinds of clay and lime plaster are masterly applied to the walls of the different rooms. The men’s bathroom most certainly is the highlight with a deep red and shiny lime plaster.

In my two days with Tokura san and Itagaki san, I could witness the climatic as well as aesthetic benefits of clay work. Especially interesting to me was to see modern adaption and usage of the traditional crafts in clay and lime plaster. I found that Tokura san’s carefulness and dedication in the construction of the clay walls are crucial to the aesthetic experience. The passion becomes perceivable in the beauty of the subtly shining lime and clay plaster walls. Beauty that empowers human and creates affection. Affection that is crucial to sustainability and resilience. Only a building that people really care about like the former Toyama residence with its deep red bathroom walls has the chance to endure and withstand.

This idea of resilience and sustainability through aesthetic and absolute carefulness in design manifested during my visit to Kyoto. Rengeji Temple and the Katsura Imperial Villa endured in perfect conditions – not due to unbreakable materiality but because it deeply touched people’s emotion and, therefore, became worth to maintain and care for. This very same idea applies to the thatched roofs, that I visited in the backcountry of Kobe. Ikuya Sagara san, a thatcher, invited me to his house in Ogo. He generously showed me some of his works and even let me assist on construction site. I still doubt my contribution to the progress on construction, but he still invited me to come back to Japan and work with him.

A common thatched roof lasts about thirty years. Especially the parts that are exposed to wind, rain and snow a lot will start to rotten – the roof needs to be fixed. Due to its thickness and the natural properties of material and construction, only the very top layer of the roof needs to be replaced completely – the layers beneath can be reused in the construction of the new roof which then again will last for thirty more years. This periodical maintenance seems to be much more valued in Japanese culture today than in what I have experienced so far in Germany. Interesting to me is the fact that humans seem to be much more willing to accept the need for maintenance in circumstances were the reasons are understandable and the effect of restauration becomes visible and therefore graspable. A thirty-year-old thatched roof may start to leak at certain points and moss will start overgrowing certain parts - visible effects that after refurbishment will be removed. Here, the effect of invest in workforce and capital becomes evident immediately.

What on first sight appears to be a weakness – the fact that adobe, clay, straw and various other natural materials are ageing under the influence of external forces like the weather can become its invaluable strength. Touched by aesthetics and the approachability, people care for the construction and seem to be willing to accept the need for on-going maintenance. Conclusion In the moment a building is constructed its decay begins. Participation in the construction of a building and therefore understanding its construction strongly increases inhabitant’s affection and willingness for on-going maintenance. A house that lasts 150 years due to on-going maintenance is much more sustainable than any supposedly super sustainable house that is demolished thirty years after its construction. Digitalization and computer-aided technology can be a great tool enabling people to experience the joy of construction. It enables us to find small-scale and very individual solutions without great monetary means. It is, by its nature, a very democratic tool and therefore accessible to a great majority of people. Constructions in adobe, clay and straw can benefit from digitalization and computer-aided technology. Building practice no longer becomes the exclusive field of a few highly- specialized experts occupied with erecting more and more complex constructions but an occupation of the public – of everyone. Architecture then again becomes “accessible to virtually everyone – suitable for small scale application; and – compatible with man’s need for creativity” – not in some romanticised way that teleports us back into long-gone times, but in a modern and yet human way that makes use of all the great advantages of technology while never abandoning its original purpose of being: to serve the well-being of humanity. Perhaps adobe, clay and straw – Japanese aesthetics as well as every construction, built with thought and great care, is the answer to urgent necessities in terms of sustainability and resilience as it orients itself towards “the gentle, the non-violent, the elegant and beautiful.” I, for myself, would like to investigate more into clay and straw and timber constructions. Not necessarily because I believe they are the only answer to a worthy and sustainable living, but because they appear to be materials of great potential that can strongly benefit from newest technology. The very material properties of clay can educate us to build better buildings and maybe to live better lives.

Acknowledgement In the end I would like to thank the BERKELEY PRIZE Committee for providing me with the opportunity to travel Japan. Experiencing Japanese culture and architecture provided me with clarity and direction – it gave substance to my ideas on architecture that before were oftentimes very vague and solely based on feelings. The fellowship provided me with an invaluable kick-off into further research that I want to conduct in the fields of traditional building materials and its possible connection to digitalization and digital fabrication. I would also like to thank Bernadette Heiermann for her great effort in writing my letter of reference, and, of course, my teammate, Henning Storch who always kept a cool head when I abandoned the path of reason during our work on this year’s Essay Prize competition.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|

1.jpg)