Sneha Varghese Travel Fellowship ReportSpain and Lesotho, Summer 2018

‘Are you nervous?’ I knew that during my trip would be I swept up in exhilarating novelty. But I also knew that unless I could comprehend that novelty I wouldn’t be able to absorb from it. I spent the months preceding my travel researching more about the spatial and cultural contexts of Barcelona and Maseru. At opposite ends of the development spectrum, Barcelona was a city globally upheld as a beacon of inclusive and creative urbanization while Maseru was the capital town of an African country still trying to rid itself of millstones like poverty, HIV and unemployment. Like hooking prologues, the imagery I formed beckoned me to uncover and indulge in the stories of these cities. Before I knew it, I was alight: rushing through airports, deciphering the language of neon signage, waiting at immigration lines, embarking, disembarking, and then repeating the process all over again. I loved the interim periods: the hours I spent wandering about, browsing through the rows of marketable units that each place’s culture had been condensed into, playing the amateur sleuth and figuring out the stories of my co-passengers. Finally, 19 hours and 3 flights later, there I was, in the city the city that Cervantes had called "the flower among the beautiful cities of the world", the city of Barcelona. Stepping out of the airport I felt the deprivation of the power of language. All around me were conversations and stimuli I couldn’t gauge from. A crowded bus, a glaring lack of net connectivity and my preconceptions about night-time travel, all combined to make my commute to the hostel akin to a blast of cold air. Slowly the dynamics at play here began to sink into me. Here, away from home and familiarity I had become a speck, an aspirant, a nameless stranger in a city. But friendly faces at the hostel, conversations with solo-travellers like me and a nice warm bath soothed off that initial feeling of disorientation. I woke up next morning prepped and ready to decipher the city, beginning at the historic nucleus Cuitat Vella or the Old City.

Cuitat Vella Cuitat Vella is an urban palimpsest. Within its fabric lie relics that narrate the 2000 year tale of Barcelona. The temple of Augustus that calls out to the 1st century B.C. origins of the city as a Roman settlement, the Park de Cuitadella that blotted out the 18th century Bourbon military fortress and the oppressive reign it represented, the El Raval neighborhood that was a succor for the workers and immigrants who fueled the 19th century industrial revolution, the network of plazas that sing an ode to the 1980’s urban reforms the city implemented post Franco's dictatorship, and the Moll de la Fusta that the 1992 Olympics left behind for the city as a lasting gift. Cuitat Vella stands as a incitement, a call to myopic urbanisation trends to pave ways into the future sans negation of the past. I began my journey at the Placa Catalunya. For all rights and purposes it acts as the city centre, a major transit junction and the symbolic juncture between the old city and the new. Ascending the steps of the underground metro felt like an emblematic unveiling: the intricate sculptures around the plaza stood as witnesses to my entry, solemnly overseeing as they had for centuries over this city. Crossing the plaza I found myself awash. I was swept in the flow of the La Ramblas street, through which human landscape of every age, colour, size and shape tumbled along, temporarily eddying at the shops and cafes along the way, before flowing again to the tune of the rustling rows of trees that guided them onward and forward. Along the banks of this pedestrian river, vehicular traffic moved unobtrusively along narrower pathways. This boulevard came to represent to me the spirit of Barcelona, not just in terms of the palpable energy and eclectic life it channelled, but also it terms of the prominent position it bequeathed to the human factor ensuring that other urban factors weren’t dominators but partners in the flow of life. Turning off the Ramblas you find the reason for Cuitat Vella’s ‘the other worldly charm’. The paved narrow streets meandering off encapsulate human scale in its truest sense. The sounds of the neighbours conversing across, enterprises functioning along, and people transiting through the streets, echo off the facades to surround you with what can only be described as the music of life. The true beauty of that music lies in its ecumenicalism; in the fact that everyone, from elderly in wheelchairs to toddlers in prams, contribute to it undaunted and zestfully.

The intricacy of these streets subtly hints ‘unless you belong you won’t understand’. But as you get lost in them you realise you don't need to understand. You only need follow. Every turn conceals a surprise. Enticing building forms peek out of vistas like clues, guiding and beckoning you. Slivers of the Mediterranean sky caught between narrow street walls seem like stolen joys. And then you stumble upon the hidden treasures- volumes brimming with light, air, shade, laughter and conversation: the public plazas. For Barcelonites public space design is political. They recognise the integral role these spaces play in promoting democratic interaction of diversities, fostering identity and citizenship, supporting the domestic spheres of life, and facilitating entertainment and relaxation. Therefore since the 1980’s they have demanded, created and cherished these spaces which usually front buildings of communal significance like churches, markets, and cultural institutions. This positioning establishes a symbiotic relationship of activation that contributes to the success of these spaces. Moving through these spaces revealed an important lesson to me, that design quality does not guarantee experiential quality. To pull up an example I would like to contrast between the Placa de Sant Miguel and Plaza Pou de La Figuerra. The former is framed by the formal activities of a town hall, public library and municipality office. Adorning the paved rectangular volume of the plaza is a steel sculpture by the artist Antoni llena. A number of facilities are provided: bike stand, play area, restaurants. Technically the space is correct, but practically, it fails. It’s a sanitised environment devoid of any trace of the chaos of life. It isn't yours and you find no reason to linger. One the other hand is the plaza Pou de la Figuerra. This space, I was to later find out, was the result of a neighbourhood struggle that refused to let the space be converted into a parking lot. Two civic organisations border it, a community center and a restaurant run by NGO. The facades that frame it are far from perfect, some needing repair, some marked by graffiti. The space tapered and contained no significant architectural form or installation. And yet within this space residents of diverse identities lounged about, watched their children play and talked to each other. Its humble design didn't stop it from engendering and supporting life.

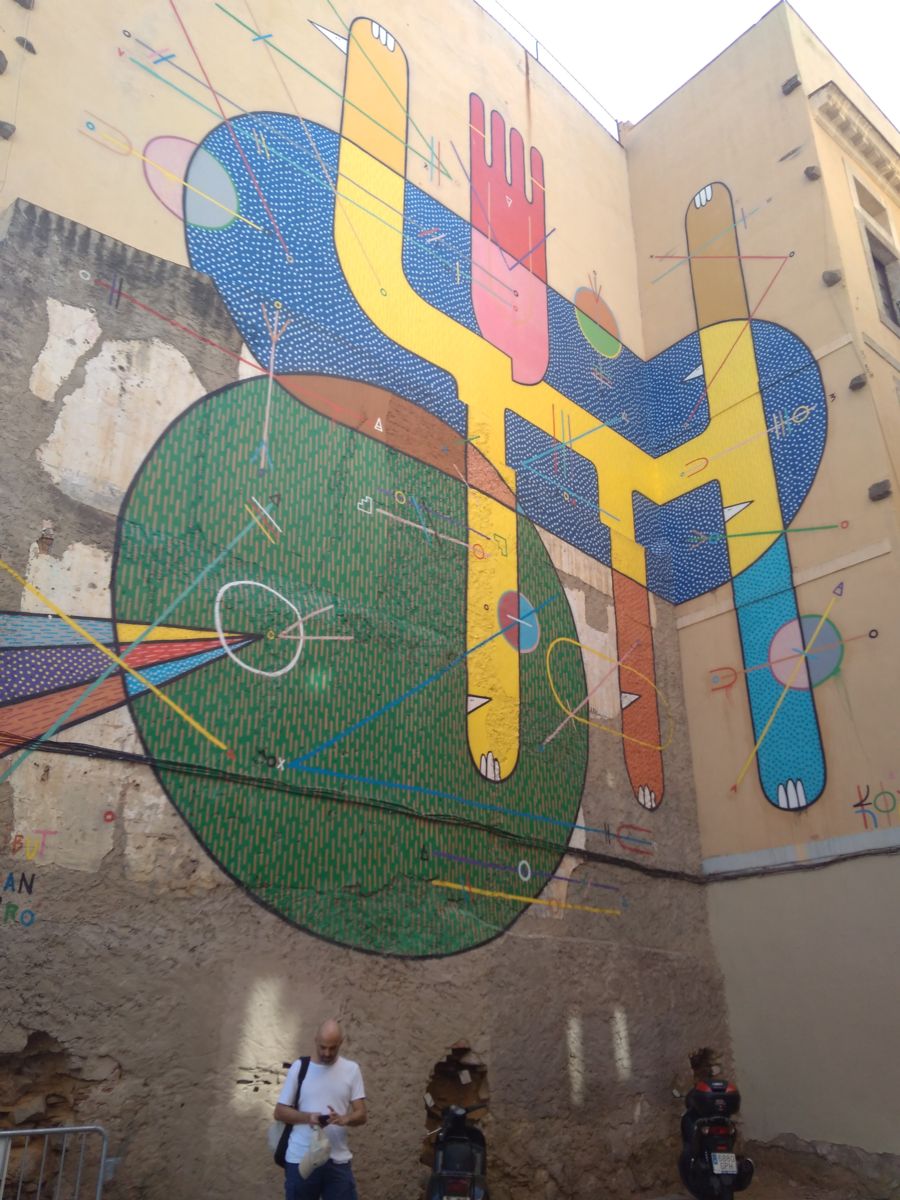

The most enviable character I found as I strolled through these streets was the degree of unabashed expression and agency. The sometimes garrulous graffiti, the posters of cultural events, the banners with political cries are all indications of that mobilisation which works through a rich network of residents associations, social enterprises and civic organisations. Barcelona thrives because participation is a way of life here. The people care enough to be involved. It's not that they are not afflicted by conflicts: the influx of tourists has eroded many neighbourhoods into tourist products, long term residents are often smoked out by increasing rents and living costs, increased immigration has brought with it problems of xenophobia and racism. They recognise these shortfalls, announce their aspirations and toil for their realisation. The city makes them feel like they belong and in turn they work untiringly for it. Eixample

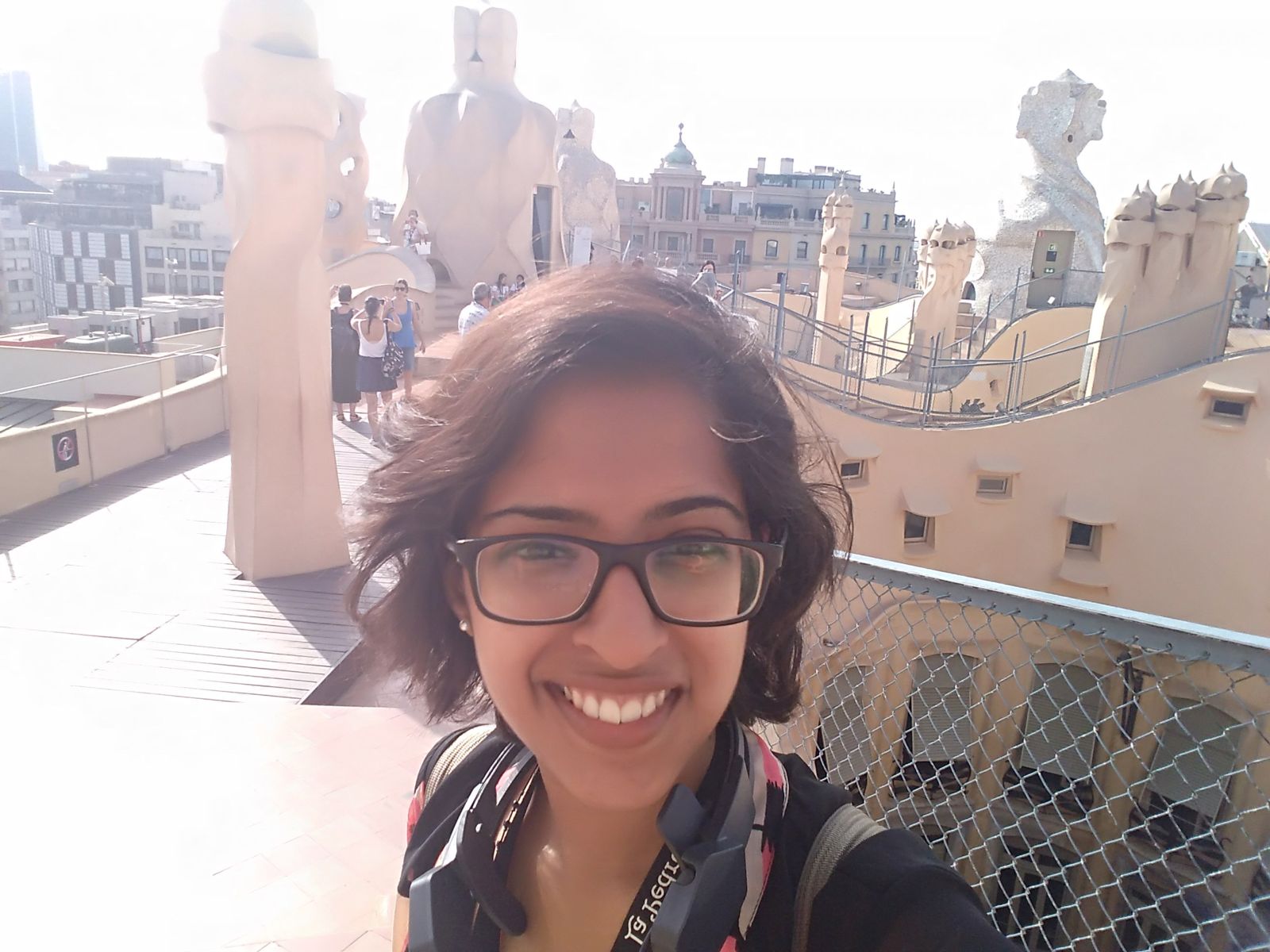

Within the history of every city there are certain individuals who prevail. They reach out across centuries to continue dictate the nature of the city. In Barcelona’s case one such person is Illdefons Cerda. 19th century Barcelona was bursting out of its seams with congestion, diseases and working class dissent choking it. An engineer by profession, Cerda proposed a grid based extension plan, that democratised services, integrated green space and planned for pedestrian and vehicular flow. At a time when monumentalist and segregated planning was seen as the solution to city congestion, Cerda saw beyond. Instead of creating an urban structure that enforced divisions he created one that emphasised commonality, every neighbourhood was treated equally and provided with accessible services and ample public spaces. His gift to this city was imageability, legibility and a blueprint for cohesion. I began my exploration at the Passeig deGracia, one of the most important streets in the district. It's impossible to walk along this street except with a gaping mouth and star struck eyes. Each façade is a sculpture of intricate details, allusive forms and opulent materiality. Some of Barcelona’s most priced architectural gems, the creations of modernist stalwarts like Antoni Gaudi, Joseph Puig I Caldalich and Joseph Montaner lie along this street. Among them I was able to experience Antonio Gaudi’s buildings. To see first-hand the light wells of Casa Batllo, to stand among the sentinels guarding the roof of Casa Mila, and to be speechlessly lost within columnar forest of the Sagrada Familia were profound moments that I couldn’t be grateful enough for. They were magical spaces that left me feeling falsely nostalgic for the age when society had the time and appreciation for works of such delicacy and eccentricity.

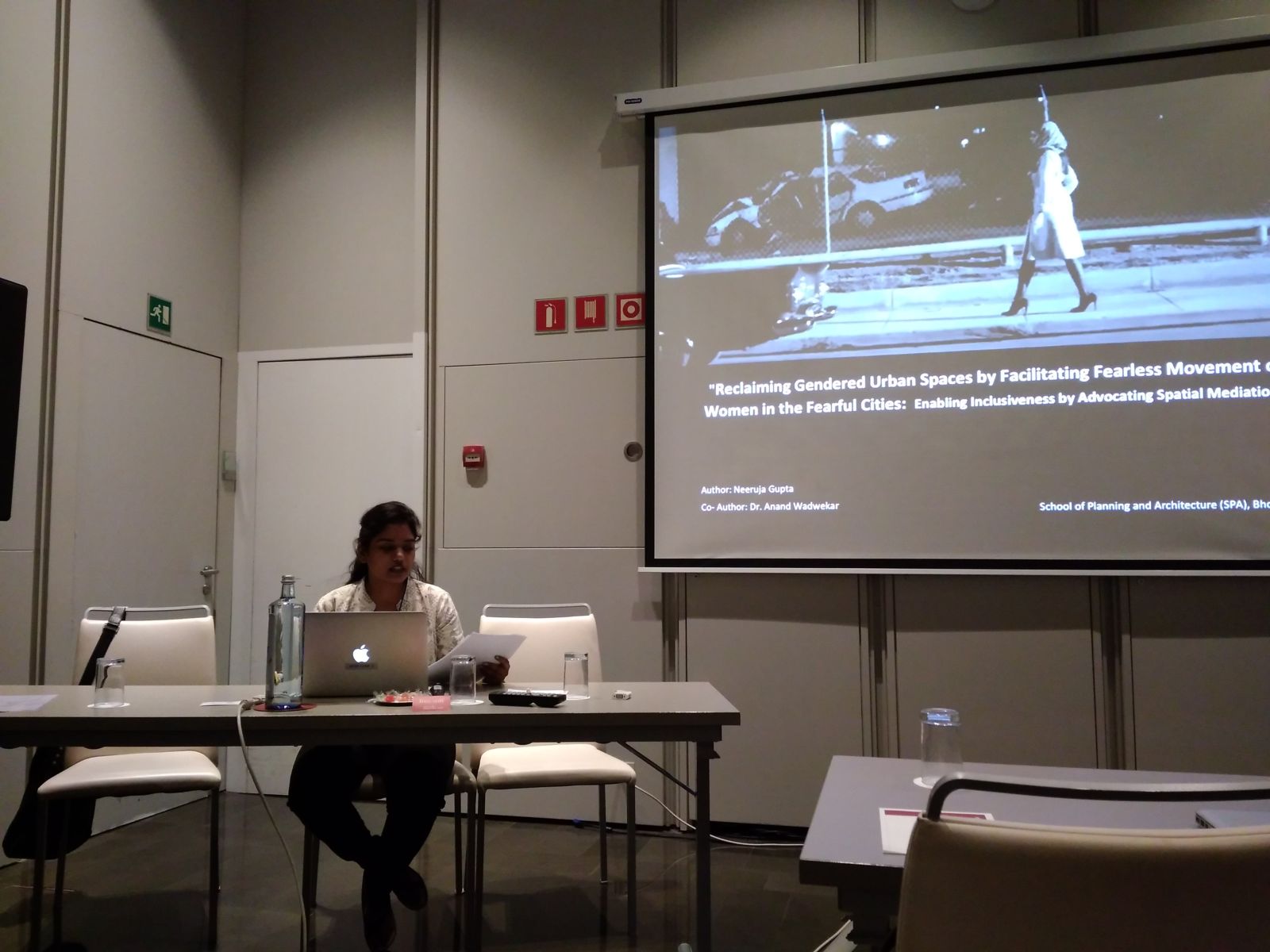

These tourist hotspots acted like central veins, the exuberance of the visitors frequenting them seeping into the surrounding streets. They are however consumer environments, meant for short intense indulgences. As you exit them and move towards the inner streets, the living breathing Eixample that Cerda envisioned slowly begins to emerge. With the simple design intervention of allotting residual space of blocks as open spaces Cerda created a network of interior gardens to generate healthful urbanity. But like with all visions, this one too got warped in translation by economic forces. The few that I visited, Jardins de rector oliveras, Jardins de la Torre de les Aigües and Jardins de Jaume Perich, seemed to be throbbing with social potential. If obstacles like the foreboding walls containing it, the orientation of buildings away from it, and the lack of formalised activity initiators were removed, they could become a network of life-force generating spatial foci. Cerda’s solutions had the practicality of an engineer. To define his junctions he merely chamfered the corners by 45 degree. Experiencing those corners put Kevin Lynch’s theories of imageability into sharp focus for me. As I sat enjoying tapas at an outdoor restaurant in one of these junctions, I was able to appreciate how the pleasing architectural forms engendered by the angular plan, the confluence of circulation pathways and the sheer availability of more air and light attracted urban functions and made these junctions vital nodes. The most prevalent impression I had while traversing these streets was that of order. Having come from environments where every inch is fiercely contested for, experiencing spaces where activities are clearly allotted space and systems to function, was enlightening, to say the least. Every street was apportioned into sections for commercial spill over, pedestrian flow, street parking, biking routes, and vehicular flow. This designation only works because it is supported by a culture of mutual respect. Here pedestrians and vehicles waited patiently for the signal before moving, irrespective of whether the other path was being used or not. Witnessing that deferential behaviour honestly made me embarrassed of the road culture in India, where mutual disregard rather than respect prevails. Conference The IAFOR City2018 conference themed ‘Fearful Futures’ was held over 3 days at the University of Barcelona and NH Collection Constanza. To be in company of professors, practitioners and students of diverse disciplines from all over the world and to be exposed to their ideas, findings and enquiries was one of the most academically enlightening experiences I have ever had. I shall now provide a brief overview of a few of the many sessions and my primary takeaways from them. Introductory Session The Conference began with sessions focusing on the current political crisis in Barcelona. Barcelona, as the capital of Catalonia has always had a strained relationship with Spain. The pages of history are rife with instances of Spain adopting a policy of suppression to keep the socialist and eclectic Catalonians under their thumb. The latest manifestation of this trend has been the Spanish government’s use of state force to shut-down the independence referendum of October 2017, which was followed by systematic arrests of Catalan nationalists. In Spain unity has come to mean uniformity. To quote one of the speakers Mrs Monterserrat, ‘In Spain unity is sacred, more sacred than dialogue and common sense.’ This ideology is at odds with Barcelona’s spirit which has always welcomed immigrants, taken pride in its diversity and valued sovereignty over nationality. While the demand for independence maybe be flawed, the fact that the way the state acted in a deliberate manner to curb a constitutionally prescribed exercise is an ominous precedent. This trend of nullifying dissent and rendering civilised machineries obsolete has been echoing around the world in recent years, and it is what leads us to the question of whether it is indeed fearful futures that await our societies.

Cities we fled: This was a panel presentation by 3 presenters Donald E Hall, Susan Ballyn and Liz Bryski who talked about the cities they fled: Birmingham, Bath and London respectively. Drawing off personal experiences and subjective observations, the session was meant to provide a counter view of cities, as spaces of fear and disempowerment and not just pleasure and freedom. Their analysis personified their cities and assumed a character for it which was often at odds with their own. For Mr Donald who grew up in the strongly conservative city of Birmingham, the environment of racism, religiosity and homophobia forced him to keep his gay identity closeted which left him feeling constantly suffocated. For Mrs Liz Bryski who described herself as an introvert, the city was too loud and exposing, even though it allowed her to depersonalize and ‘to see without be seen’ at times. Their viewpoints however presented a separation between their own identities and that of their cities, which was called to question by the audience. The ensuing discussion concluded that though their dispositions seem disjointed from that of the city, they were part of the body of contrasts that influenced and altered the city. For example, during Mr Donald time in Birmingham he partook in the underground disco culture that supported the gay subculture and in that sense shifted the character of the city more towards one that could be his refuge. Informal settlements and regeneration factors in rural-urban continuum: Hassan Afrakhteh, Kharazmi University, Iran This presentation focused on informal settlements and the different parameters that are used to define and tackle them. By taking the example of the Harandy region in Tehran, he showed how the locational-geographical and the pathological approach have resulted in one-sided solutions like monetary schemes for poverty reduction, empowerment schemes, or renewal programs that fail to provide comprehensive upliftment. His analysis looked at the specific problems that plagued the area and identified the kinds of deprivation that resulted in the prevalence of these vices (namely resource poverty, power poverty and opportunity poverty). The description of the Harandy region struck me as an old story in different words as I realised the concurrence in processes of alienation around the world. It led me to question if to some extent the growth of informal settlements is inevitable, if urban growth and inequality are somehow two sides of the same coin. To this question, Prof Hassan replied he didn't believe that it was. We know that the solution lies in ensuring that the distribution of wealth that is matched by a distribution of power. All we need is the will to implement this ideology. In this age of globalization it would not be an exaggeration to say that technology is taking over the world. We are becoming increasingly cosseted by information and communication systems which have come to gain global representation as problem-solvers. The drivers of urbanisation too have adopted this rhetoric and championed the cause of ‘smart cities’ as the answer to the social, economic and environmental questions surrounding urbanity. Ms Amanda Ahl posited that this idealistic perception of ‘techtopia’ has brought about many harmful effects. Being a process that requires extensive funding it is usually accompanied by increasing privatisation and loss of public space. There is the aspect of social marginalisation as groups incapable of accessing and utilising this smarter machinery slip through the cracks. I could relate to her observations having witnessed similar processes in India, where there is increased popularity of smart city proposals that more often than not utilise top-down approaches to formulate elitist and non-contextual plans. She did however recognise the immense potential technology presents if it is sensitively used. She took examples of two cities, Barcelona and New York, whose smart city exercises were framed around citizen involvement and invited solutions from the community rather than imposing them. She emphasised the need for cities to carefully consider social equity, scalability and affordability, methodology in their implementation of smart city development.The risks of Techtopia- Reviewing negative lessons of Smart City Development: Amanda Ahl, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan Distributed Citizenship- Spatial Interventions in the public spaces of Athens: Angeliki Sakellariou

Interview with Collectiu Punt 6

Though the mere experience of Barcelona urban planning had imparted vital lessons on facilitating inclusivity it was imperative that I back my observations as an outsider with the perspectives of citizen experts. I therefore met with Maria Roser of the Collectiu Punt 6, which is a cooperative social enterprise of feminist architects, sociologists and urban planners who aim to democratise planning by including gender issues. The following is an excerpt of my interview with her. Could you give me a brief of your organisation’s projects and the methodologies you adopt to achieve you goals? Would you say that Barcelona is gender inclusive? Is Barcelona safe for women? Which is a better strategy for women safety: security or autonomy? To answer your second question, definitely autonomy. We advocate informal surveillance over formal. Statistics have revealed that women feel safe when overlooked by people, but police have the opposite effect on them because they connote hostility and prejudice to most women. It's important to ensure the limits to accessibility are removed. The efforts should not focus only on physical manipulation but should be backed by social-cultural efforts too. For example lighting: some people think lighting up the space can make it seem more safe, but the fact is that irrespective of lighting if there is no vitality the space will feel threatening. What are the methods to ensure that meaningful participation, especially of vulnerable groups takes place? Lesotho On 19th July, I left from Barcelona and began my 19 hour journey to Lesotho to participate in the Rise International in-loco built workshop. The in-loco program is a “learning-by-doing” experience meant for local and international architecture and construction graduates to improve their skills by aiding in the construction of an extension for the God’s Love Orphanage in Maseru. To the uninitiated, the African continent represents a bleak picture: provincial people, dry landscapes, arcane beliefs, poverty and disease. A place that's needs fixing. Most people feel impelled by altruistic responsibility towards it; a responsibility that sometimes arises from an intrinsic presumption of their superior human condition. My thoughts weren't much different before I visited Lesotho. I wanted to give more that I wanted to get. But in the transformative, paradigm-shattering and profoundly sentient experience that followed, I got much more than I gave. Though it might sound romanticised, in my short but intensely beautiful 10 day stay, I undeniably fell in love with Lesotho, it's people and it's spirit. The flight from Johannesburg to Maseru was on the cutest plane I have ever seen. The 30 seater plane flew at a very low altitude which meant I had could experience an uninterrupted montage of the famed African landscapes. As the 45 minute flight ended and we disembarked, I found myself facing the emptiest landscape I had ever seen. I stared at it a while longer and I realised it wasn't it's emptiness but it's purity that had staggered me. It was pure of any signs of human appropriation, just smooth brown contours, a lonely tree here and there and an azure blue sky that held it all together. I took a deep breath and felt for the first time in a long time, the profound contentment that came from comprehending beauty at scales much larger and more encompassing than our tiny human lives. Outside the airport, Daniela, the program director was waiting for me. She welcomed me with so much warmth that I almost forgot that I was in a foreign environment. On the ride to the hotel she explained the current status of the project, gave a few pointers about Basotho culture and the introduced me to the layout of the town. She spoke about the town and its people lovingly, like they were her own. In her descriptions and in the passing landscape, I began to feel the vibe of the place. It was almost like everyone was a long lost friend to each other, the cheerfulness in their interactions apparent. By the time we reached the hotel, I realised the anonymity I had grown accustomed in Barcelona would no longer be available, that my experience of Maseru would involve intimate indulgences and would hopefully be punctuated by lasting connections and friendships. It didn’t take long. Once he got over his qualms about communicating in English, Mokhele had much to say about his town, his people and his life. As we walked around, he gave me descriptions about the different buildings of prominence. Like most towns stepping into urbanization that list was topped by the expansive, flashy malls scattered around town. They were the dock where global franchises and products found their outlet into the city. I asked Mokhele if the mall was a common hangout spot among the youth in the area. Contrary to what I thought he said it was, but not for him. He was from a rural area and malls were alien environments to him. ‘They are for the rich few’ he said, ‘not for us working classes’. His answer made me appreciate how disparate our individual stories were and how lucky I was to have this platform to listen and understand from such authentically new stories. Most of the structures had limited architectural form, restricting themselves to one or two floors. The buildings that stood out were the public infrastructures, like the library, the National development center, the Standard lesotho Bank and a sports center. Mokhele also took me to show his university which though small, he described with so much pride, that I realised it was more important than its size indicated. Our last stop was the markets whose ordered chaos momentarily transported me back home. Walking through the sea of people, the stacks of staple to exotic products, the cacophony of bargains and transactions, I began to appreciate the similarity between the Indian scenario and the African. The aspiration that coloured spaces in developing countries. The apparent conflicts and contrasts that were manifestations of the population’s strive for upward mobility.

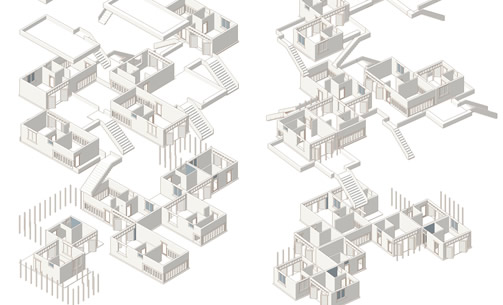

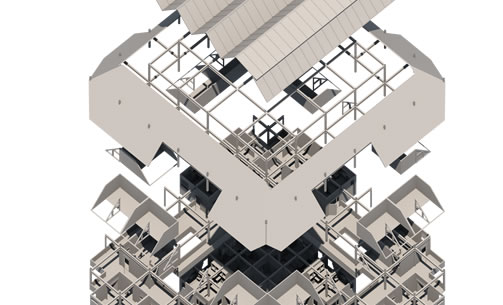

The next day was also a day of exploration for me. Thandi, an architectural student and a fellow at the program took me to visit the Kome caves. Located 2 hours outside of town, the journey gave me a chance to view the rural side of Lesotho. It was fascinating, to see a life so far removed from the noise of modernity, where life progressed unhindered devoid of things we regard as basic necessities. As I watched these traditional Basotho folk standing along the road, cheering our vehicle on, I couldn’t help but ask myself if theirs were limited lives or is ignorance truly bliss. During the ride, Thandi shared with me some of the folklore surrounding a sacred mountain we passed on the way. More than the story I was fascinated by how their stories survived. Their respect for their roots is seen not only in their conversations but also in their architecture, with buildings still utilising mud plastering, thatched roofs and patterned facades. It isn’t parochialism; it is sensibility in identifying the value of sedimented knowledge and techniques. It is a rare quality, one that India forgot in it blind mimicking of the white man’s imagery and it can only be hoped that Lesotho does not give it up in the race for development. In my interactions with Thandi I also began to grasp what they meant by post-colonial hangover. Thanks to colonisation we had a common language to communicate in. English had established itself as a prime vernacular; the respect associated with mastering the white man language apparent in society. It wasn’t just English, it was the popularity of English media too. Here, continents and countries across, Game of thrones was still the best TV show ever made and Beyonce was still queen. It did feel beautiful to discover those far-reaching concurrences, but it also indicated an inimical dilution of variety and a certain bias that centuries post-colonialism we still can’t seem to shake off. Having developed a picture of the culture and context I looked forward to the next day when I would be introduced to site. The first agenda for the day was a site meeting. Luca, Daniela, the foreman, the site manager and the buyer all filed into the small room that was functioning as site office. The meeting began with a progress update from each person. The reasons for delays were identified and responsibilities were assigned. Questions regarding the design were brought to the attention of the architect. It was my first experience being a part of a session like that. And it was insightful to see the way in which the smooth functioning of the logistical hierarchy was essential to the project efficiency. After that Adrian and I were taken to the existing site of the God’s Love Center where we were to meet Mmneo, the head of the orphanage, and the 50 children under her care. Along the way Luca explained to us about the design problem that had come up during the meeting. In order to provide insulation for the homes, they had adopted a double wall design: a concrete layer and then a brick layer. As the architect, Luca had suggested that the brick wall be constructed in a pattern format; placing bricks alternatively length wise and breadth wise to create extrusions. In addition to providing a pleasing texture it would connect to the traditional style of construction in Lesotho. However, this style took longer and more effort to construct. For the fellows, who were used to the stretcher bond, it was an uncomfortably new. But Luca wanted to progress with it because that was what the aim of the project was: to help the fellows to think outside the box and to recognise the value of innovation. He felt that though it was difficult it was a value-adding exercise. It was the first instance of the push-pull between external expertise and internal workmanship of which I was to witness more in the coming days.

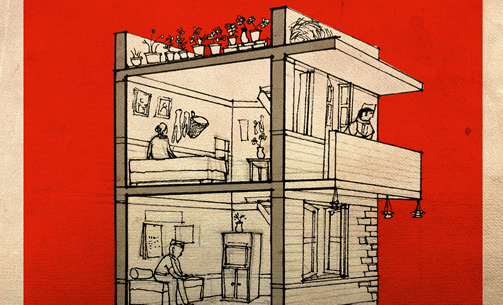

Nearing the orphanage we could hear the laughter of the children from the street itself. It was vacation time for the children, which meant that they were always out and were always playing. The orphanage itself was a small concrete structure with two rooms, one hall and a kitchen. There was a container which was being used as a school and a store house at the edge of the site. The place was stretched to its maximum capacity, crammed with children of all ages and only a handful of staff supervising them. Showing us around the house, Luca pointed out the portions that required urgent attention. This included the front yard too, where a vegetable garden, a swing, a septic tank and toilets were haphazardly positioned. Before leaving, Daniela showed us the storage area where piles of clothes had been heaped together to be discarded. They had accumulated because of well-meaning but unnecessary donations. Daniela asked me to look into any means through which those clothes could be remade into useful products, which I agreed to do. The next day I started with my Mat project that would help reuse the used clothes. I scoured through a couple of youtube videos and came with a resource efficient and simple way to make it. The two carpenters working on site, Mokhele and Rakhibe, helped me with the initial cutting of wood pieces to construct the mat frame. Then they taught me how to use a drill and fix the pieces together. Abuti, a 10 year old differently abled kid at the home, joined me in fixing nails on the frame. Wordlessly he sat next to me, helped me mark the points, watched me hammer the nails in, and brought to my attention the shaky ones. I was talking to him, without saying a word and that exchange left me feeling weirdly filled, with both intense happiness and profound sadness. Once the frame was done, I cut the t-shirts into strips to prep for the knitting process.We then went to the construction site and ‘got our hands dirty’. I was assigned to help the brick laying team. The fellows eagerly taught me the tricks of the trade: setting the line, mixing the mortar, laying the brick, tamping it, filling the mortar. After a few sloppy tries, I got the hang of it. I was beginning to experience the joy of physical labour. With conversations, jokes and sometimes even singing, we had a jolly good time working hard. On the second day, Luca asked me to go to the existing site and come up with a design outline for a play-castle that would help structure the front yard. Kobo, an architect fellow volunteered to help me. We began by measuring and marking the perimeter. Soon the kids gathered around us curious to find out what was happening. On hearing that it was for a play-castle they excitedly began to throw in ideas and suggestions. They shared how currently it was too sunny for them to play because of the orientation of the swing and the lack of trees. The boys said they wanted more space to play football, while the girls complained that they didn’t have enough space to play their games. The environmental factors hindering their play had driven them to play in front of the storage shack. I spent the rest of the day working on their inputs and coming up with a simple L-shaped play castle design that would establish a corner and define their space. I also marked out landscaping to soften the sunlight and improve the usability. As I was preparing drawings of the design, the children gathered around to question me about my life in India. Their innocently inquisitive questions ‘Is every one in India rich’, ‘Does everyone have hair like yours’, ‘When are you getting married.’ were so adorable. They also told me about their life: their favourite singer, their favourite subject, and their ambitions. It was a heartily engaging day. Day 4 was spent making the first prototype. The process was simple; it involved tying t-shirt strips of two colours in a criss-cross fashion and sewing them up at the junctions. As I doubtfully made the first stitches, the girls in the home gathered around me, eagerly offering to help. They astutely watched me and without any further explanations from me, took out their threads and needles and began to work. Soon it went from an experiment into a group event. There an exquisite feeling of sisterhood as all of us women of different ages and cultures, gathered together to create this one work of art. As they learnt how to make the mat, they tried to teach me their language, albeit I must confess, rather unsuccessfully. Within a few hours, we had finished and as I was cutting the mat out of the frame, Mmneo, the founder of the home, walked in to survey the final product. To see the look of joy on her face and to hear her say ‘It is beautiful’ was a more than enough of a reward for me. The next day was a half day. We were to have a guest lecture by Luca, our architect. I decided to spend the morning finding about the capacity building portion of the program. In their assessment of the God’s love Center, the Rise team had realised the need to back the provision of infrastructure with organizational support. They wanted to help the elder children set up small businesses, like poultry farming and an internet café, to improve their entrepreneurship skills and establish a flow of funds. They also hoped to equip the staff with ample skills and knowledge to responsibly care for the children. Tsietsi and Mammatli, the two social worker fellows, who were assigned with this responsibility, shared with me the obstacles they were facing. The push-pull between external expertise and internal workmanship had led to the current staff feeling defensively territorial. Though they were appreciative of the inputs being provided, there was inertia towards change. As I helped Tsietsi and Mammatli prepare a workshop on ‘Protocols for Child Care workers’, I was able to get a better picture of the social engagements that need to supplement any act of physical engagement in the development field.

In the afternoon, we went to the university were the lecture was to take place. Luca’s presentation, titled ‘Process as an innovation’, outlined 3 of his projects, a biking track, a farm and an exhibition pavilion, each of each involved a process that was derivative rather than imposing. The biking track was developed by a process that involved multiple community engagements and catered to the biking culture prevalent in the area. The pavilion which was to be a temporary construction was designed to be reassembled as a school in a refugee camp. The farm was developed through extensive research on natural systems, sustainable farming methods and interaction with the farmers. The lecture gave me additional perspective on how to practice sensitivity and sustainability in the architectural profession. The weekend that followed was one of the most fun filled I have ever had. Visiting the Thaba Bosiu cultural village, the hangout spots of the fellows, having traditional Basotho food and going horse-riding for the first time, I couldn’t help but envy the Basotho people’s proclivity for fun. I found myself immensely comfortable in their company, loving their energy and finding concurrence with their tastes. It was the beginning of friendships and the making of memories that I will always cherish. I had only 1 day left, and that impending end made me savour the labour more. I spent it working on the roof of the orphanage, fixing the holes with waterproofing membrane against the beautiful backdrop of the Lesotho skies. The last day ended more quickly than I thought and I as I bid my goodbyes to the children and to the fellows, I couldn’t help but feel the pang of separation. Today, as I sit in the familiarity of my home, writing this report and regurgitating these memories, I feel myself brimming with gratitude. Towards the Berkeley Prize Committee, for giving me this once in a lifetime opportunity, my parents for supporting me despite their apprehensions, my brother for always encouraging me to be better, and to divine providence for gifts I am and am not aware of. In my gratitude, I also hope; that this cataclysmically enlightening indulgence shall be the first of many, that I shall always strive to look beyond my paradigms, and that my values achieve legible fruition in my work. With that gaze to the beyond, I end this report.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|