Gunraagh Singh Talwar Travel Fellowship ReportGambia, Summer 2018

|

.jpg) |

Karsi Kunda – the village without lights |

On Tuesdays, Musa takes his horse cart to a market in Senegal where shops for necessities that his family requires. After the tiring day at the market, he comes back with a wide smile on his face, often bringing back an apple or two for his kids to enjoy. Relishing Attaya – the local tea, he spends the rest of his day resting. The day culminates with the family taking dinner from a common bowl, reciting Namaaz.

The Village of Karsi Kunda lies in the far eastern, Upper-River Region of The Gambia. The people are predominantly farmers and pastoralists who rely on the annual monsoon for their survival. For the rest of the year, the people enjoy their produce, finding odd jobs in their interim disguised unemployment.

The Nka foundation, recognising this under their umbrella of human capital development proposed Kantora Arts Village, a complex with independent units taken up for the 2018 Design Build Challenge by workshop leaders from all across the world, set to be constructed from June-December 2018.

Build With Gambia

Erika Alatalo, a Finnish architect and traveller took up the idea of a dormitory building for the project. Beginning her journey from North Western Africa, and travelling south towards the site in Gambia, she studied traditional knowledge systems prevalent in the region, ultimately deciding on the Nubian vault technique owing to the lack of structural timber. The first attempt at the vault marked the beginning of the participatory design process that is the core of Build with Gambia. Together with ten local volunteers, Dodo – a Western Gambian artist, and Robin – a Scottish carpenter, the team put up a vault through trial and error. The result was what the locals labelled a Buntaba – a community place.

.jpg) |

Erika Alatalo, with Dodo – a Gambian artist |

The constructed vault was imperfect – it required scaffolding, did not follow a specific arch, and was developing structural cracks. To perfect the technique, Erika looked consulted the Nubian Vault Association in Burkina Faso, an organisation that trains masons across western Africa, and builds over 500 structures each year, with this she realised the potential and limitations of the technique and began working on the design for the dormitory.

.jpg) |

The Buntaba |

The Gambia

I reached the coast of Western Gambia in late May. It was a few days until Erika was to return from her trip to Burkina Faso, so I spent my time exploring the city of Serrekunda. I had observed the rich red-brown soils of the country while flying above, but was surprised to see concrete as the most prevalent construction material. Where I expected to see humble structures exploiting the potential of laterite, I saw framed glass boxes. Here, I found hope in what I was here for. Build with Gambia was not just a dormitory building from rural youths, but also an example of how simpler, more rooted techniques made better buildings than conventional practice.

Design Development

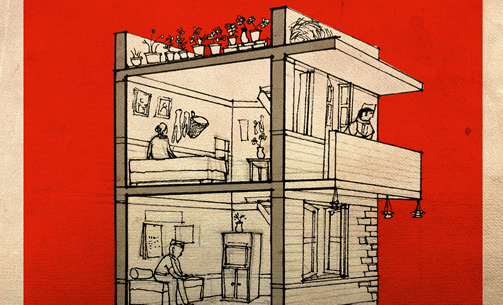

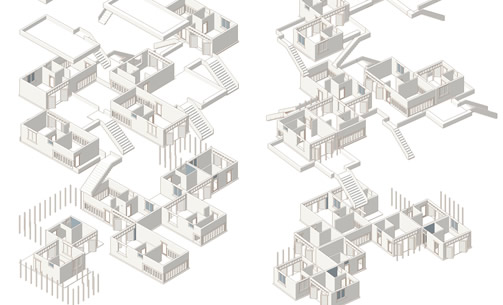

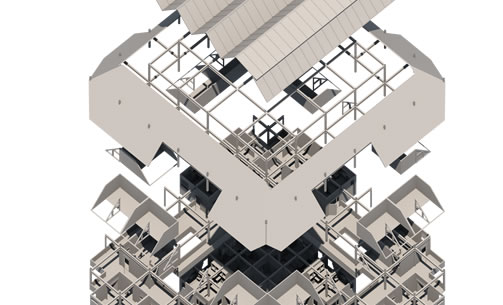

My first interaction with the design for the dormitory building was a breakfast table discussion with Erika. Sure enough, Erika had understood the potential and limitation of the vaults well, designing a functional and climatically responsive architecture comprising of three private dormitory volumes, and one volume forming the toilet and baths. A doubly loaded corridor integrated these volumes forming a semi private space.

Nubian vaults on rammed earth walls formed the volumes, giving the structure an accessible roof for the users. Plastic waste is a predominant problem in the village, and so I proposed an earth bag staircase, which the design incorporated by a simple lateral shift of volumes.

Having have not been to the village yet, I could not comment on the contextual aspect of the design. I did feel however that the design could do more on its experiential quality. More aspects that needed resolution pertained to construction, like waterproofing, and minor details. I sought to work on all of this during my tenure as an international volunteer. The idea of using seashells for their inherent lime was proposed, and so we collected seashells from the beach before making way to the village.

Building with Gambia

June 01 – June 14

Travelling to the village of Karsi Kunda is like travelling back in time. Streets get narrower; buildings get lower before turning into thatched roof mud huts; and amongst all observable things, the mode of transportation changes from a public bus to Musa’s horse cart. I received a warm welcome while entering Musa’s Jarra-Sanneh compound, and with all that took me time getting used to, I was excited to build with Gambia.

.jpg) |

Kassi Kunda – A mix of traditions and convention |

Since the project was to commence, the ten-man team, which had previously volunteered their services, now expected salaries - equal wages for all workers irrespective of their skillset. The concept went against the participatory aspect of the workshop, but it was decided that the pay be given not as a wage, but as a scholarship from Build with Gambia for skill development of the people. Since all the villagers were fasting due to Ramadan, workshop hours were relaxed to four hours until June 14, the day of Eid.

The first day on site involved marking the foundations for the dormitory building. As the men dug the foundations, Erika and I, along with a few children started collecting stones needed for the foundation. The Buntaba, which had been cement plastered while Erika was away had started developing structural cracks. I proposed to test out various mud and lime plasters after removing the cement plaster. The upcoming monsoon would test out the plasters, and the best one, used for the dormitory building. The improvised vault structure of the Buntaba however collapsed during removal of the cement plaster. The workers did not take the event too well, but this signified them taking ownership of the structure. We reinforced the idea of rebuilding the structure – the Nubian way, perfecting the technique before it took form in the dormitory.

Groundnut innovations

So began a long phase for the reconstruction. Rubble from the structure was moved to a nearby patch of land, put water on, and remoulded into new, lighter bricks for the vault. Since straw is not available in peak summer, I proposed the idea of using groundnut shells, which are abundant and find no other use. In a day, the women from the Jarra-Sanneh compound excitedly arranged for a huge bag of groundnut shells, which found use in the mud mixture.

The worth of a Line

What seemed like a couple of lines on paper while we marked the site for foundations took a full working week to dig out. Filling them back with stone was another task in itself. Erika and I had collected a pile of small stones, which was clearly insufficient for the foundations, and we asked the community workers to help with the stones. Several donkey cart trips later, we could say that we now had enough stones for one-half of the foundation. Developing a proper masonry technique for the stones and filling in took another week.

Often we as students think conceptually while designing, forgetting how much effort it might take in getting it to manifest. Design solutions should not necessarily be simple, but effective.

June 14 - Eid Mubarak

The wee hours of June 14 was a very merry time in the Karsi Kunda. The end of the long period of 1Ramadan meant a time of feasting and festivities. Everyone was dressed in fresh tailored clothes, the kids flaunted creative hairdos, and everyone enjoyed the day greeting and talking amongst one another. For Build with Gambia it meant a deeper insight of the community and working in full blaze.

.jpg) |

A meeting with the village elders |

June 15- June 28

With the foundations and vault, proceeding at their own pace, there was time to think and resolve other design considerations. In the absence of lime, and with the intent of not using cement, a plausible solution to waterproofing was baked tiles. Since the village of Karsi Kunda possesses no technical knowhow of baking clay to form water resistant terracotta, and procuring the tiles from neighbouring villages and towns are not feasible, it made sense to develop the technique on site with the design of a clay oven.

Vaulting gaps

A project that I took the initiative of, construction details for the oven stand an example for the dormitory. A vault using the formwork of a barrel covers the oven, which can become an arched lintel for door openings. The walls aside the vault are similar to the detail of the Nubian vault. The door opening is a cost effective method of making openable windows, and the plasters done with the intent to test out in the rain. The entire oven was done using extra bricks from the previous construction, and a piece of scrap steel mesh. . As a surprise element, the design for the Chimney also doubled up as a small coal stove to brew Attaya in. The oven is located in a interstitial pocket between the upcoming dormitory and the reconstructed Buntaba. Here it aims to create a dialogue between the structures and later act as a kitchen unit for the dormitory.

.jpg) |

The development of the clay oven |

Construction of the oven though was not as smooth as its design development. While the ten-man team showed a lot of interest as I had started working, the failure of three vaults due to uneven ribs in the formwork barrel made them lose interest. Only when the vault stood with its adjoining walls that they actually started being appreciative. Salifu, a member of the team and a man with a history of baking bread in Mali was especially interested in my intent for the oven and joined me to help with the plastering.

Four kinds of plasters were thought of for the oven; mud, mud and sand, mud and crushed seashells, and mud studded with seashells. Salifu expertly plastered a base coat of mud plaster to refine the oven’s shape, followed by the plasters, and a coat of sealing palm oil. I even developed a plaster-spraying machine mimicking one I saw in a neighbouring village, but with scrap.

.jpg) |

The plaster spraying machine and the result plasters |

Soon after, sample tiles were fired in the oven to test out the potential. The tiles were semi-baked, but brittle because of the consistency of the clay used for them. Salifu suggested that I use a different mixture, and I was onto it when my time in the workshop came to closure.

.jpg) |

Musa’s son helping fire the oven and the first test tiles |

When life gives you lime

.jpg) |

The local lime is coarse, it needs filtering, but can provide an interesting textural experience if used as is. |

James, the local welder at Fatoto later told us about a place in Western Gambia where people burn Seashells to form lime which can be used for a waterproof plaster, which we procured through a trucker in town. The community was interested in the new material, but did not initially have faith in it. The lime was slaked and used as capping for the oven, and owing to strength also realised for plinths around the dormitory building.

June 30-

More volunteers arrived after me, carrying the responsibility of Build with Gambia as they added onto the project. I have been up with the project, if not physically but virtually through social media, and Angela Kim, a volunteer from U.C Berkeley through the JLS Traveling Scholarship.

The project is schedules for completion around September-October 2018, and may be followed by the below-mentioned link:

https://www.facebook.com/buildwithgambia/

.jpg) |

Sarjah enjoying his cup of Attaya during lunch |

Additional Help and Information

Are you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org.

Nipun Prabhakar (BP 2014), Buddhi Bahadur’s House, Siddhipur, Kathmandu

Valley, Nepal (Undated)  Nipun Prabhakar (BP 2014), Nunnery, Remote Himalayas, Nepal (2017)  Aparna Ramesh (BP 2013), Cottage for Children, Bangalore, India (2015)  Aparna Ramesh (BP 2013), Cottage for Children, Bangalore, India (2015)  Holly Simon (BP 2011), Justin Loucks, Phil Wilson, Kevin Lo, The Public Speaker,

Calgary, Canada (2015). Photo Credit: Stenhouse Photography  Holly Simon (BP 2011), Justin Loucks, Phil Wilson, Kevin Lo, The Public Speaker,

Calgary, Canada (2015)  Neelakshi Joshi (BP 2009), Soso House, Ladakh, India (undated). Photo Credit: Sonam

Wangchuck  Neelakshi Joshi (BP 2009), Fieldwork at construction sites, Himalayas, India (undated)  Philip Tidwell (BP 2003) and Peripheral Projects Studio, The Säie pavilion, Helsinki,

Finland (2015)  Philip Tidwell (BP 2003) and Peripheral Projects Studio, The Säie pavilion, Helsinki,

Finland (2015)  Tarun Bhasin (BP 2015), World Architecture Festival Student Charrette Entry (2016)  Tarun Bhasin (BP 2015), World Architecture Festival Student Charrette Entry (2016)  Clarence Lee (BP 2014), interior design for young couple and child, Singapore (undated)  Delma Palma (BP 2014), a planned mixed-income development, Washington, D.C.,

USA (undated)  Delma Palma (BP 2014), an affordable apartment building, U.S.A. (undated)  Ben Wokorach (BP 2013), Fruiti-Cycle First Prototype, Kampala, Uganda (2016)  Ben Wokorach (BP 2013), Fruiti-Cycle Second Prototype, Kampala, Uganda (2016)  Andrew Amara (BP 2006), a workshop to engage local families in designing

affordable and sustainable shelter, Kampala, Uganda (2016)  Robert Ungar (2010) and ONYA collective, a garden in a formerly abandoned entrance

to Tel-Aviv Central Bus Station, Tel-Aviv, Israel (2015)  Robert Ungar (2010), Grassroots 2015, a community organized festival in ONYA

collective garden, Tel-Aviv, Israel (2015)  Avikal Somvanshi (2008), The Ladder House, New Delhi, India (2012) |