Meghana Hegde Travel Fellowship ReportBerlin, July-August 2016

Design Build in Berlin : Community spaces for refugees How does one try to integrate a displaced and fractured community in a cultural and social setting quite different from its own? How does one try to find cultural common ground between incoming refugees and locals in Berlin? These were some of my core concerns for the Design Build Summer School as I set out on my sojourn. The four week long intensive Design-Build summer School was conducted by Cocoon studio, an enterprise comprised of Technische Universitat Berlin faculty, but working as a separate entity. Cocoon has been involved in a number of university level Design Build programmes in different scenarios, some of which are in Cairo, Berlin and Oxaca in Mexico. I arrived in Berlin a few days before the summer school started on Monday 25th of July. I believe my first impressions of the city really helped me gain a deeper understanding regarding the objectives of the Summer school. First Impressions of Berlin Berlin is complex in its urban make-up and so much more interesting because of this array of diversity. Owing to its storied past, Berlin feels like many different towns stitched together with swatches of beautiful greens. Walking through the different city neighbourhoods is like a visual narrative of all that has come to pass here.

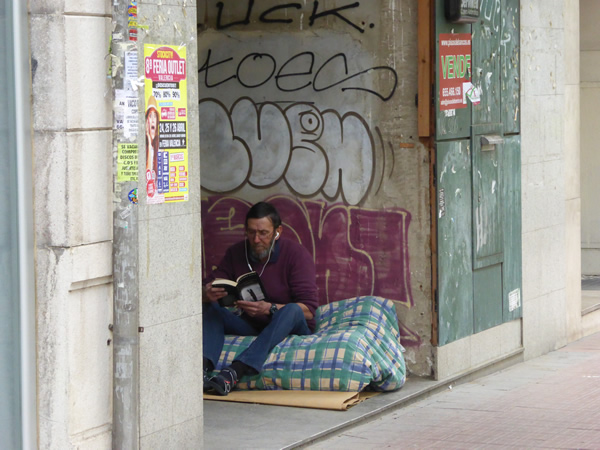

What really struck me in my first few days, living alongside and interacting with other students is how core cultural values viz. collectivism v/s individualism differ for different countries and how strongly they affect the lives we lead. This cultural polarity of individualism v/s collectivism, further struck me while we were trying to analyse the lifestyles of locals and refugees during the initial design phase of our exercise. Background to the Design Build Summer School With 80, 000 refugees arriving in Berlin in 2015, the city has been grappling to deal with such unprecedented numbers. Temporary fixes to shelter the refugees, only increases their dependency on the system. This further leads to insecurity amongst both the refugees and the locals. The ideal situation would be, for the refugees to coalesce and assimilate with their adopted communities. In Berlin’s northernmost Pankow district, Buch is an idyllic dreamy residential suburb. Seeming quite lost in time Buch feels as far removed from the city centre as possible. As untouched by time as it seems, paradoxically it is one of the urban locales that act as a setting for refugee camps. Buch is home to nearly 500 refugees living in the container housing AWO refugee camp. With another two container villages planned for 2016, these numbers are on the rise. Even prior to this Buch had already been earmarked as one of Berlin’s 10 “transformation zones” (STEK 2030) focusing on population growth.

In line with the projected growth of both refugees and locals in the area, Buch was decided upon as the locality for our Design Build programme. Within Buch, an old sports field adjoining the Panke stream, was selected as the venue for our intervention. The sports field was originally used as a football ground but 30 years of disuse had left it overgrown.

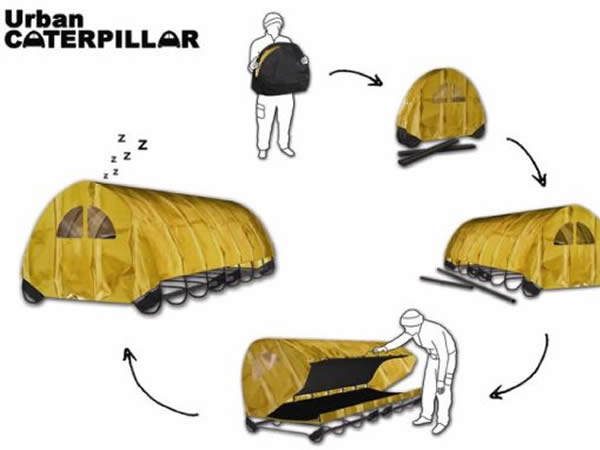

So, the objective of the summer school apart from addressing the social element of refugee-local integration also was the revitalization of the sports field known as Panke Feld. The local Buch community and administrative bodies hope to develop the sports field into a full-fledged sports ground with an accessory building, in the not so distant future. Accordingly our design build outcome was envisaged as being an initiator towards that goal. Towards that end, part of our design task was to outline a feasible site plan for the Panke Feld and the other part included building a prototype/(s) on site. Design Phase The 4 weeks of the summer course were broken down into four one week phases: Phase 1: Initial mapping of site and design visualization Phase 2: Presentation to the community and detail planning leading to finalization of designs. Phase 3: Detailing out the work plan and prefabrication Phase 4: Prefabrication, building, installation and inauguration. Phase 1 The first week started off with a visit to The Kitchen Hub and Inselgarten. The Kitchen Hub is an indoor dining space with flexible use furniture, which was developed under Cocoon studio’s 2015 Summer school programme. It was envisioned as a space where refugees and locals could collectively cook and share meals. Having had breakfast at the Kitchen Hub we experienced first-hand how the furniture and spaces around it function. Breakfast was followed by a lecture from Florian, a T U Berlin faculty member , about various landscape level design build projects they had conducted in the past. This introductory session really helped orient us and give us a better idea of how landscape design build projects develop. Following the introductory session we went directly to our site in Buch to survey the field and collect our first impressions of the site. The whole summer university team consisted of 21 people from 14 different countries with diverse backgrounds. Subsequently, four teams were formed to initially map out the site and then to further work on design proposals for the site. The second day of the week started with a tour of the Hans Scharoun designed architecture building of the Technische Universitat. I was awed by how sublimely variations in scale and irregular angles were harmonized to create grand and yet intimate spaces. After the previous day’s site studies our teams came up with initial ideation sketches to explain leitmotifs regarding the feasible usage of the site apart from the sports facilities, which were a given. Our group came up with the idea of creating a forum sort of space, open for discussion and sharing of ideas. Along these lines, a huge sharing table was conceived of. As we understood it, we thought the sports facilities would be used by the younger demographic but so much by the older folks. Reflecting on this, we thought of all the common elements that could be cross-generational and cross-cultural. The thought behind the sharing table was to have a universally common platform where people could come and talk, interact , play games, share food and in due course find their own use for the table. The other groups came up with various ideas such as a platform styled seating stage, reclining benches modelled on flying carpets, mobile outdoor furniture and variations of sheltered outdoor spaces.

Further discussions at this stage amongst all groups led to resolution of initial sketch ideas and firming up the strengths of each team. For the following week our initial ideas had to be presented to the Buch community. Phase 2 The second week commenced with a public presentation of our design ideas to the Buch community. The audience included local residents, local politicians, sports authorities and representatives from citizen help groups. After a long day of presenting and discussions, the Buch representatives reverted back with what designs and elements they liked. I really appreciated this open discussion of ideas and democratic process of design selection.

Of the many concerns that were raised one was regarding overhead shelters. Consequently, given the stringent local buildings laws for structures and budget and time constraints, it was decided to forgo all fixed overhead structures. At this stage the selected design proposals were further whittled down to form concrete ideas regarding their construction and execution. The total autonomy given to us to experiment with different ideas and materials is something I really appreciated. Phase 3 Week 3 started off with us finishing off our detailed drawings and working on material lists and costs. The practical feel of moving towards realising our designs was enthralling. However due to budgetary constraints and site restrictions, there being no electricity and water supply on site, proposed designs further had to be changed to make construction feasible with our short one week time! This week we also focused on reaching out to the refugees as well as the Buch community. Raising awareness of our project meant that more would accept it and be supportive of the endeavour. We also hoped that trying to bring people to the site and take part in the building process would give to the community a sense of ownership of the site. A football event was organised on the newly cleared football pitch in order to raise awareness about our renewal project. There was a very positive response from both the refugee and local Buch community.

Following the success of the football event, we went back to work with renewed vigour. The next few days we focused on preparing the wooden materials for construction and prefabrication in the university workshop. Phase 4 The last week was our main building phase. We had readied all our material and now was the time to implement our designs. The excitement on the field that first day of work was palpable. Using an on-site generator for electricity we went about preparing foundations and assembling the prefabricated elements.

A total of 5 design interventions were being built simultaneously on site. The excitement,confusion and anxiety of working on our own designs propelled us through the next few days. The final intervention elements included :

On the final day after completion of work, a small informal inauguration ceremony was held. This was followed by an informal gathering where people from the neighbourhood, refugees and locals alike came together shared food, played football and explored the renewed and renamed Panke Platz. In our short 4 weeks right from surveying to finishing up work and clearing the site, I believe our end result validated the original objectives.

Conclusion The initial response to the outcome of our 4 weeks of hands-on work seemed very positive, with quiet a large number showing up for the opening. The real test of viability for the project will be the acceptance and continued usage of this space.

The Panke Feld project was an immersive and intensive, student-driven project. It called for a lot of teamwork and mutual co-operation. Through its outcome, It really goes to show that the smallest of initiatives can maybe bring about change in the social behaviour of people. In a sense the Panke Feld project is an experimental initiation towards a larger goal of both, regeneration of a dead social space as well as bridging the gap between socially non-cohesive communities. It has really helped me appreciate how small well-intentioned interventions can influence social change. This whole exercise has helped me experience first-hand the impediments and obstructions socially driven design faces. At the same time it has made me understand how designing to overcome and even embrace such challenges is what makes social architecture so enriching . It has made me introspect on how architects can move away from the corporate realm of large scale, mass produced structures to really make a positive change in lives with small scale interventions.

Acknowledgements I would like to thank the BERKELEY PRIZE for the incredible travel opportunity that the fellowship provided. The crux of my travel plan was to attend the Design Build – Community Spaces with Refugees Summer School programme at T U Berlin. The course of my travel gave me the opportunity to meet incredible people and engage in cross-cultural exchanges of ideas and ideals. These experiences are priceless and have left a deep impression on me. I would like to thank my professors , Mahesh Bangad and Shubhashish Subandh for guiding me. I would also like to thank the Summer university professors Ursula Hartig, Jan Gehling, Simon Colwill, Nina Pawlicki and Rucha Kelkar for being so encouraging and supportive throughout all the stages of ideation and execution. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents for everything.

Additional reading : http://karow-live.de/2016/08/10/der-neue-sportplatz-in-buch/

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|