JENNISSE SCHULE TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP REPORTAlaska, USA, July 2015

Habitat for Humanity has a vision, “where everyone has a safe and decent place to live,” where housing poverty and homelessness are eliminated” worldwide. This vision fit what I was hoping to learn about when embarking on the Berkeley Travel Fellowship. I had two primary goals when choosing Habitat as my travel fellowship opportunity of choice; the first goal being to learn how houses go together and secondly, to learn how to make them as efficiently and inexpensively as possible in a cold climate. There were several organizations that I considered but many organizations do not build homes in cold weather climates and if they do, they are not for low or no income housing. Habitat for Humanity Anchorage had an active build site in Anchorage, Alaska. As a student architect, it is very important for me to come out of school with the skills that will allow me to become gainfully employed. Architecture as an industry has had to change with the rising use of 3D modeling software programs, such as Revit. A graduating student no longer comes out of school and goes to work at a firm where their drawings are redlined and then given back until proficiency is gained. The software programs require a knowledge of how a building goes together, structurally, from the first mouse click. Some architecture school’s curriculum has had a difficult time bridging the gap this new technology has created. Architecture students now need to know, at a much more advanced level than ever before, construction skills and software skills, besides the regular design skills. I wanted to learn, as much as possible, in a short amount of time, hands on, how buildings go together. Besides working for a construction crew, Habitat for Humanity has an excellent track record of working with people with little to no previous construction experience. This makes volunteering a rather painless experience. Our team of volunteers included first time and many repeat volunteers from across the nation ranging in ages from 16 to 71. Each of us had a different motivation for coming together but we all approached each other with mutual respect. Being with such a diverse group of people can have its challenges. This group had little to no such challenges. My sense from speaking with other return volunteers while this is not always the case, it is more the norm than the exception. The team leader is a part of this success. A team leader is responsible for building their team. At the initial discussion, the team leader can recommend a variety of volunteer opportunities and has the ability to shape their group. Projects vary around the world from housing to community improvement. Depending on the location (or affiliate) that you choose, the build project could be in a variety of stages of development. A build location can be such as ours was, in various stages of development from just the foundation to finish work. Or it can be done all in the same time frame or stage of construction so all volunteers are working on the same stage of development. This is more characteristic of smaller projects. Each team builds at a different rate of speed depending on the dynamics and size of the group, as well. As Affordable Housing is a significant problem or buzzword in most communities in the United States, an organization that is building houses with volunteer labor and donated money to put them into the hands of people who cannot afford conventional means of a mortgage is commendable. Habitat for Humanity Anchorage had an active build project that fit the criteria of learning how buildings go together and certainly qualifies as a cold weather climate. Homes need to be efficient all year round to remain affordable after they are built. Our mission is to work in partnership with people throughout the community to build hope, build houses and change lives. We do this by building and renovating simple, decent affordable houses and by using our voice in the community to make adequate housing a matter of conscience and action. Habitat is a hand up, not a handout. Habitat for Humanity-Anchorage is an affiliate of Habitat for Humanity International - a nonprofit, Christian housing ministry dedicated to building simple, decent, affordable houses in partnership with qualifying low-income families.

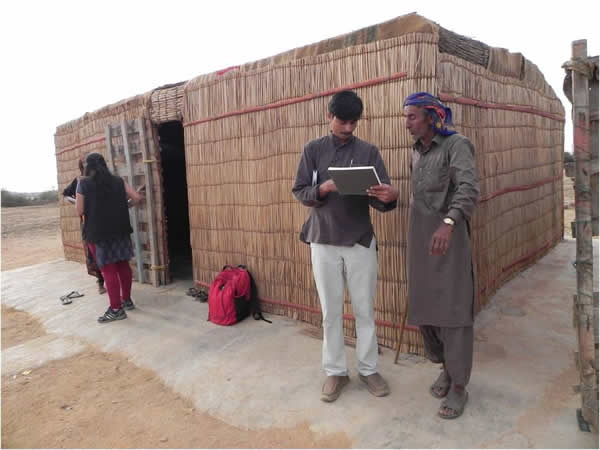

According to RSMeans, building with SIPs saves an average of 44% per year in energy usage depending on climate and width of the panels. Using the calculator for Climate zone 6 from Big Sky Insulation’s website (one of the manufacturer of SIPs panels locally (Belgrade) and the manufacturer for the panels we installed in Alaska from their sister factory in Puyallup, Washington (bigskyrcontrol.com/sip-calculation-result/) calculates that is an average savings for $639 for the first year and $42,430 over a 30 year period, even with a 5% annual energy cost increase. For comparison, the Climate Zone of 8 (Alaska) reports for the same size house (long and narrow at 25’ wide by 60’ long with 10’ ceilings, one story), at 46% savings for $885 the first year and $58,764 over 30 years. This also assumes as close to a conventional built home as possible. If the SIPs panels are increased in width, the savings increases considerably. Habitat homes are mostly built by volunteers. On our team, there were 23 volunteers and 6 on-site supervisors (full-time employees of Habitat). The use of volunteers increases the time needed to build the homes as every week a new team of volunteers arrives on site. And it requires a certain kind of crew leader or job supervisor, almost a teacher rather than a builder. Every crew leader had an excellent way of teaching new skills and a very high degree of patience. In addition to the rotating volunteers, Habitat’s business model requires the homeowner to help build their home or someone else’s. Each affiliate establishes sweat equity hours that are required to be completed by the new home owners. Our team worked with several different home owners during the time we were there. One of them was the owner of the house my particular team was helping build. The new owner was clearly proud and honored to be able to help build his own home. He was already working two other jobs but arrived on the site several times full of energy and smiles. The purpose of this rule is to provide the home owner with minor construction skills often needed by a new home owner to maintain and upkeep their home. But it is also part of the volunteer model, the more hands on the project, the less money spent and the more projects can be built. Most importantly though, I feel it gives the new owner a much greater sense of pride than simply being handed a set of keys to a house. This is a rare opportunity most home owners do not get to experience.

A second goal of going to Habitat for Humanity was to understand how the organization helps eliminate poverty, especially in the United States and specifically in a state where the climate is cold, similar to Montana. Poverty in the United States often does not look like poverty in other parts of the world, like India, for example. We are simply not that populated. Our poverty is more subtle and often involves an automobile as part of the equation. If you cannot afford a car, you often cannot afford to work, simply because you cannot get there. In Montana in particular, there is little housing, let alone affordable housing, within walking distance to jobs and often public transportation is not a viable option. Especially in my home town of Kalispell, Montana (where I wrote my original paper) the bus service is simply not widespread enough nor does it provide or offer enough service pickup times to be a viable means of transportation to the largest groups of jobs in the town. Poverty in the United States can be easily recognized in the case of homelessness but other people just as bad off may not be so easily seen. This is in part due to a social stigma but again, also because our states have less of a percentage of population, our problems are more spread out. For example, a man may be buying food but it is all the food he can buy for the month with $20 he was given from panhandling north of town. A woman lives in her truck and showers at the gym. She goes to work every day and no one knows she is living out of her vehicle. A child arrives to school with the same clothes every day and no lunch. Her parent cannot afford school lunch. A man lives at the camping ground and then moves south when it gets cold. An elderly lady walks to the restaurant for the only meal she will eat today and knows they will give her free coffee. She sits at the table until it is a bit warmer outside. She couldn’t pay her heat bill this month. Poverty looks very different on multiple levels in the United States but that does not mean our people are not poor. Habitat for Humanity is one of the few organizations that consistently makes a difference in providing affordable homes that they own. Each state and city can form its own affiliate of Habitat for Humanity International. Each affiliate has some latitude to run their non-profit according to the needs of their community. Some affiliates require more sweat equity hours than others or mandate certain other restrictions on their new owners. They may also have a ReStore, a second hand store where community members can donate their household items and construction products to be resold at a discount. The ‘profits’ of a successful ReStore are often enough to build one more house in that community. There are many other Habitat programs such as Build-And-Bike where you bike across the country and build homes along the way. Each country has different build programs.

By the numbers:

Habitat for Humanity seems to be on the forefront of having a reliable and consistent method for building homes, seeking donations and volunteers towards that end. They have mobilized globally. They are not without criticism, however. Habitat was recently criticized for their slow response to the housing crisis after Hurricane Katrina. Advocates for Habitat defended themselves by saying Habitat does not have a crisis housing model; their system cannot be sped up to provide homes faster. I do not see this as a valid criticism for the same reason as advocated. Having seen how the system works, it would be very difficult to build an all-volunteer home in less time even if the need is great. Habitat has also been criticized in some parts of the country for building inefficient homes that were inexpensive for Habitat to build initially but too expensive for the new homeowners to heat once they moved in. While this may have happened in other affiliates, it was clear that HFHA was very concerned about the efficiency of its buildings from the materials selected to the installation. While we were only volunteers, our crew leaders made sure that the installation was correct and did not jeopardize the integrity of the building envelop and no shortcuts were taken on insulation or any other necessary efficiency. One of the crew leaders affirmed that the housing costs in Alaska can run over $600 a month to heat a home. He reported that the heating bills of the homes we were building (similar to the ones that had been completed) would have heating bills 70% than the average Alaskan, including himself. This decrease put the heating of their homes into the realm of reality for the new residents. Habitat’s format involves individual “affiliates” in the United States or ‘national offices’ overseas to govern the projects and their ReStore’s (a second hand store for housing materials and other goods). Profits from the ReStore go back to the individual affiliates to fund more home projects. The ReStore is run by each individual affiliate and can be run very differently from affiliate to affiliate. Pricing is not consistent even from day to day or product to product and sometimes the store can be too generous in accepting donations that should probably go to the local landfill instead. Running a retail store with only volunteer assistance will not be without problems. Every ReStore I have been in across the country though provides an amazing way to reuse building materials. As such, it is a very sustainable way and often inexpensive way of finding lightly used construction materials and other household items. I found Habitat for Humanity Anchorage to be a very heart warming and transparent organization. They recognized their shortcomings but tried their very best to do right by their families, their staff, their volunteers and the community they served. In my limited experience, they know they aren’t perfect but try to do the right thing every time.

Alaska is a very unique part of the United States; it is isolated and with that comes a sense of independence and fierce pride. Consumerism is lower in Alaska as goods are more expensive. Items are used longer and reused more often. Garbage is hard to deal with as it is expensive and difficult to remove, especially in the winter months. Jobs are difficult to come by and at times offering lower pay or significantly higher pay for similar jobs in the lower 48. Alaskan residents enjoy an annual stipend from the oil companies paid to every Alaskan resident after living in the Alaska for a year. Native Alaskans and Native Eskimo have special fishing privileges and are offered lower cost health care and other amenities. For parts of the year, the sun barely, if at all, sets. For other parts of the year, day light happens in a blink. Many businesses operate on a 24-hour model, especially fitness centers. When the sun never rises or sets, it is much easier to not have a normal 8-5 day. Still, in spite of the potential of a harsh life in Alaska, US Census reports that the poverty level in Alaska was 9.9% for 2009-2013 compared to a national poverty level of 15.4%. While they may have a low poverty rate, Alaskans are struggling to find jobs. The Bureau of Labor reports Alaska’s unemployment rate is 6.7% reported in July of 2015. This is the third highest in the United States behind West Virginia 7.5) and Nevada (6.8) and compared to Montana’s median value of 4.0%. As Alaska struggles to redefine itself amidst declining fisheries and other industries based on nature, increased reluctance to mine or frack the Alaskan wilderness for gas or oil and other environmental challenges, it has a model for a sustainable, efficient and affordable home building model that perhaps be applied outside of Habitat for Humanity on a greater scale, maybe in other parts of the country. Overall, I learned a lot and met both of my goals. The trip was a valuable experience for me on a number of levels including socially and professionally. The lessons learned and the friends made will stick with me for a long time. Still, I am left with more questions than answers. On the education front: I still do not know how to successfully bridge the gap in my school’s curriculum without working for a construction company or a larger architecture firm after graduation both of which may require me to move outside of Bozeman, Montana. The larger question for students much younger than me, perhaps, might be what kind of architect do they aspire to be? They would do well to make sure they have the skills they need to be the kind of architect they want. There may be roles/jobs in architecture that do not require so much construction knowledge or help train you if your schooling has not yet adjusted to fill that gap. Or perhaps you ask many more questions of your school and see if they have been able to be quicker in changing directions in the last 5 to 10 years than most educational facilities are able. On the not-for-profit/affordable housing front, I am struggling with finding a home myself. I am making strides towards assisting in a design of a home that is small and affordable and uses the SIPs panels. I hope to be able to assist in the construction process to continue what I truly enjoyed with Habitat in Alaska; getting dirty and seeing something get built from my combined efforts with others. Hopefully, I can bring in other students to learn what I was able to learn in Alaska and keep learning. I am infinitely grateful for the BERKELEY PRIZE Team for their efforts every year. Without the BERKELEY PRIZE, I would never have had this experience. Thank you very much for the opportunity and challenge to be a better architect in every way, every day.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|