Revathi Roopini Travel Fellowship ReportMALAYSIA AND INDONESIA, JUNE-SEPTEMBER 2014

Ian Hall, the founder of Arkitrek, is pioneering an architectural practice with a green conscious in Kota Kinabalu- Sabha, Malaysia. His practice designs and constructs projects that are sensitive to the ecological wealth that surrounds it and empowers the community at the same time. The design and build camp conducted annually is one of their sustainable business models. Every year participants from different countries come together to build a project in a remote rural area. The money collected as fee goes towards its construction. On one hand the participants have a hands-on learning experience and on the other the community gains a service which otherwise may not have been possible and in return volunteer their help onsite. The 2014 camp brief was to construct a tagul hut in Kampong Maligan, a Murut village in the south western mountains of Sabha. The tagul system is a traditional system of conservation to protect the riverine eco-system. Like a traffic signal, it demarcates a green zone where fishing can happen all year around, a yellow zone where fishing can happen at certain times of the year and a red zone where no fishing is allowed. The red zones are areas of fish breeding and by protecting these stretches the fish population can replenish itself contributing to a healthier ecosystem. Over the years the tradition has faded and over fishing and fish bombing have a negative impact on the river. Understanding the vital importance of the tagul system, the Fisheries Department has now institutionalised it. Ms. Angelica, the head of corporate social responsibility, (CSR) of SFI (the paper production industry in this district) has been working with the people to successfully implement this system.

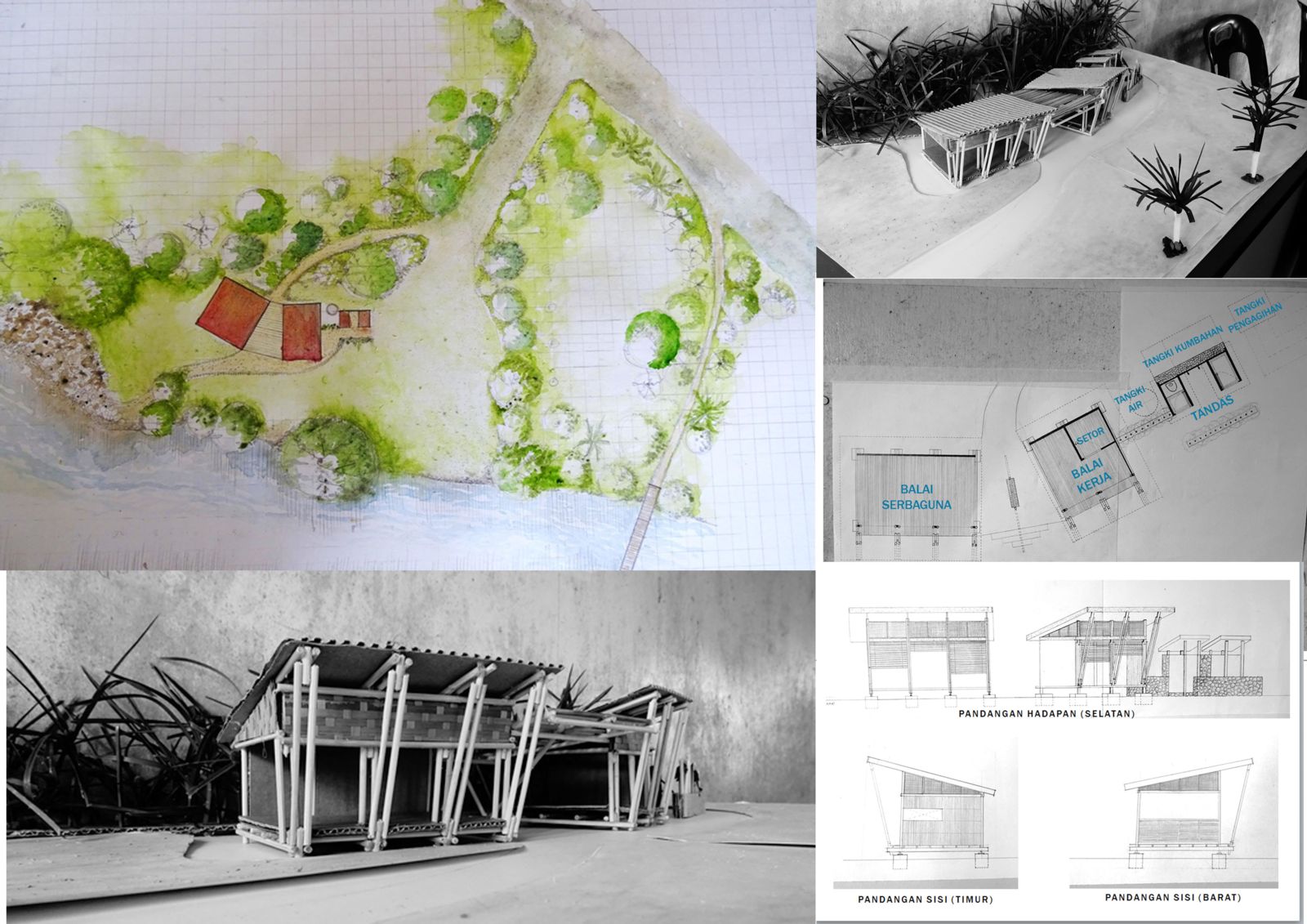

Traditionally, the tagul zone is protected by a family and the role of tagul chief is successively inherited by the future generations within the same family. This family enjoys a tagul hut, a recreational retreat where they can feed the fish, swim and camp. The fisheries department transferred this responsibility from one family to the entire community. The tagul hut is then a community centre enjoyed by all. Their vision includes generating income through tourism and starting a bazaar to sell handy crafts made in the village. Our main objective as a team was to design a building which was contextual. A design that reflected the Murut tribe’s cultural values but at the same time appealed to their aspirations. The project through its design, construction and community engagement also aimed to reflect upon the larger global issues relating to sustainability and spread awareness about environmental concerns.

Keeping with Arkitrek’s ideology of eco-sensitive design, we had a series of workshop and lectures before we went to site to educate us on several topics such as passive design techniques, earth bag construction, biocrete, timber joinery etc. The knowledge we gathered helped us make suitable design decisions on site. We consciously attempted to reduce the embodied energy as far as possible by using local materials and install systems which enable the building to function sustainably. Bamboos as a design element - Not only do conventional building materials have high embodied energy but are difficult to acquire and transport to remote sites. On the other hand, bamboo grew in abundance around the village. With borax treatment it was possible for us to treat the locally sourced bamboo on site. The craftsmanship and local knowledge also meant that we were able to use it to make panels, silu walls and even a section of the roof. The locals mistrusted bamboo as a building material (even after the borax treatment) so much that even after our insistence they were not eager to store the remaining borax for future use. As an experiment to alter their perception the toilet block has bamboo purlins whereas the other buildings have timber purlin. They can now see the bamboo last as long as the timber (since it’s well protected). Reclaimed timber- unlike other parts of the world, all timber found here are hardwood and are extremely good in quality since they are from the tropical rainforest of Borneo. Arkitrek provided us with reclaimed timber from their other project sites. The villagers also contributed any spare timber they had. Even though they were difficult to build with since they needed to be cleaned and were of different sizes, we were able to reduce our embodied energy by using recycled and spare timber as far as possible. Biocrete walls- this technique of construction involves mixing lime and sawdust or rise husk and compacting it within a framework make of plasterboard on one side and plyboard on the other. When the wall hardens in three months’ time, the plyboard will be removed and the exposed surface can be plastered. The biggest advantage of biocrete is its porous nature which allows it to absorb moisture in the air and reduce humidity; naturally regulating internal temperature. In remote sites and rural areas it has a huge impact as it utilizes agriculture waste and waste from site. Services- the community insisted on a fully functional toilet system. Hence our design became mono-pitched so that rain water can be harvested from the roof and used for the plumbing services. We also fixed a first flush diverter (made with two empty tin cans) to divert leaves away from the water tank. The sewage coming from the sink and toilet is directed into a septic tank. Once treated under anaerobic conditions, the sewage is then directed through a leech field. The nutrients from it then feed the garden planted above it. Community engagement- Right from the very first day the community received us warmly and were very eager to help us and interact with us. Gotong royong is a traditional agrarian practice where members of the village come together to help their neighbours with their fields during times when large manpower is required. This practice also extends into community life and the village activities (such as cooking feasts or clean-ups). When announced over the tanoy system in the church members of the community made time to come help us on site on several occasion Our main challenge was to find a meaningful way of interaction so that there is a mutual exchange of knowledge contradictory to the urban practice where the workers are perceived only as labourers or man power. As stated above, we integrated several sustainable and new concepts into the design and in return we learnt the ‘kampong way’ (village ways) of doing things. An example of this is the central bamboo roof. The technique of constructing the half- culm bamboo roof is not known to everyone in the village, seen nowhere in the village and seen by us only in the heritage museum in Kota Kinabalu. In the same fashion we learnt random rubble masonry from the villagers. We were fortunate enough to showcase such dying traditional techniques of construction in our building. Our interactions with the community also took forward Arkitrek’s theme of sustainability outside the site by organising an awareness program about plastic for the children. Our initial idea was to spark an interest in environmental issues in these kids. We brainstormed on issues which concerned them and decided to tackle the issue of plastics since the kampong has no recycling system. On our first meeting we had a dialogue with kids about plastics and had them collect bottles lying around their school. We then played a few games with them with the bottles. Over the next two weeks we encouraged them to collect as many bottles as possible and with their help incorporated them into the building.

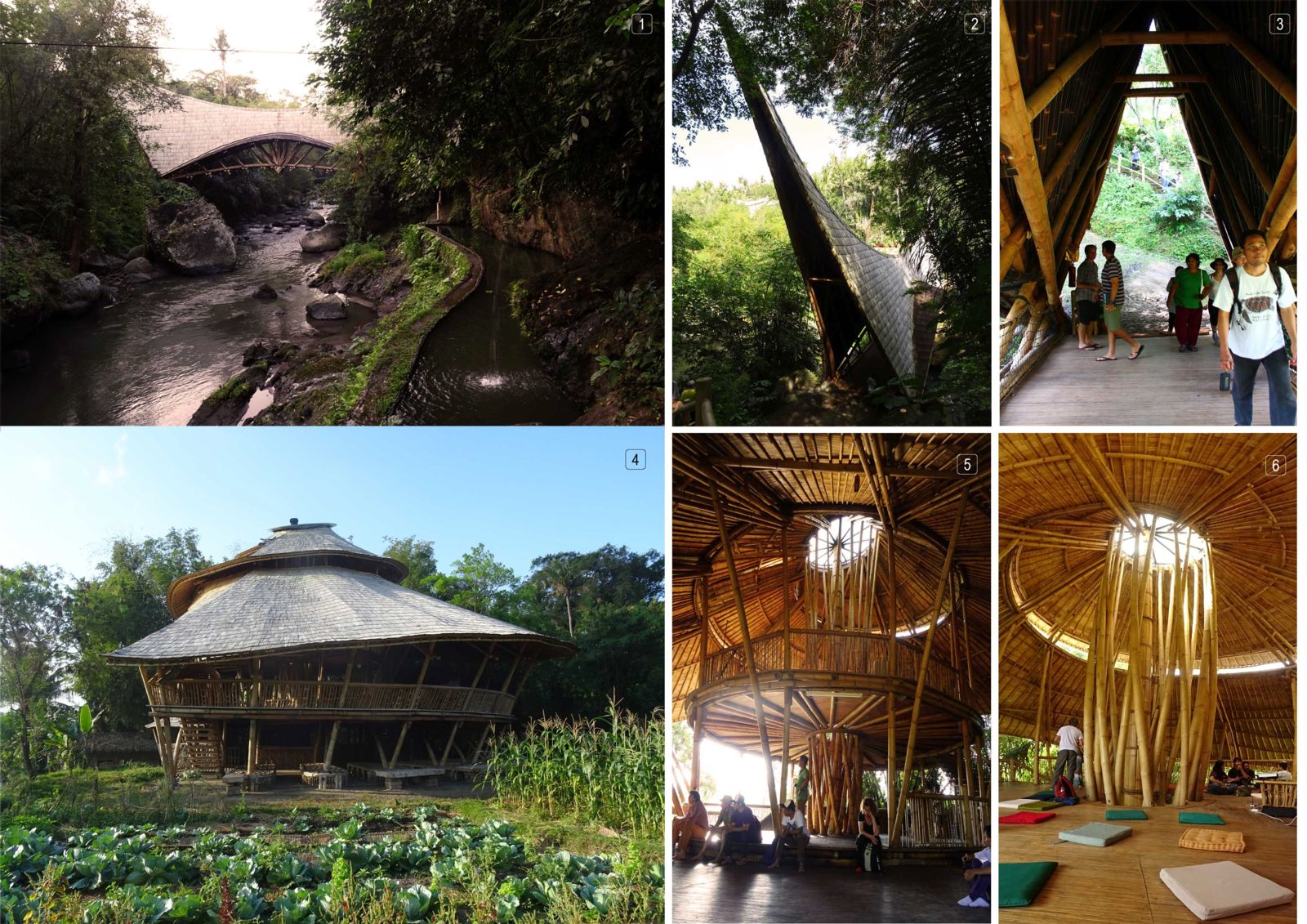

As we spent more time and interacted with the community we built interpersonal relations binding us emotionally with the community. This experience has been extremely humbling. Not only have I learnt a lot about design and alternate construction techniques but experiencing village life, and working hand-in-hand with the villagers and my team members on site everyday has altered my perception of architecture as practiced in offices where designs are reduced to only drawings. The act of building and designing gained more significance and became a process of social interaction and community building. Exploring Green School Bali, Indonesia: The second part of my journey took me to the Green School in Bali, Indonesia. In 2006 John Hardy (website: http://www.johnbali.com/) sold his jewellery business to pursue his dream of starting a school. Reflecting on the inadequacy of the education he received, he envisaged an environment which nurtures young minds towards a more sustainable future. With a strong belief that the physical environment can sculpt a child’s character, he wanted a campus that reflects his ideals. It all began when a young lady named Linda Garland noticed a giant bamboo outrigger when sailing in a traditional Indonesian boat. Fascinated by it she demanded to be taken to the place it grew. Her curiosity pioneered the start of the Environmental Bamboo Foundation in 1993 to experiment with bamboo and brought it into the forefront as a sustainable building through her research of its treatment methods. It was Linda Garland’s passion towards bamboo that convinced John Hardy to choose it as the material to physically manifest the world he envisaged. The innate characteristics of the bamboo have been exploited to create natural forms that blend into the landscape; creating spaces that blur the boundaries between the inside and outside.

The bridge was the first structure to be built to test the material’s potential. Oren Hardy (John Hardy’s son) recalls his disbelief when his father told him that he will be building a bridge strong enough for a car to pass, entirely out of bamboo and making it possible within a few months. The Balinese craftsmen, Joerg Stamm, a German builder along with artist Aldo Landwhe are the key contributors for making this happen. The team developed the design and construction technique for the first building, a kitchen now called Aldo’s kitchen. The construction techniques developed includes the central column tower and lidi- a style of making flexible beams using split bamboo with which organic forms are possible. The successive buildings have all refined these methods. I got an opportunity to explore green school and learn more about it by attending a 5 days’ workshop titled Bamboo U from the 8th to 12th of August. (Website: http://www.greencampbali.com/newsite/event/bamboo-u/) Day 1- The first day started with an orientation session where all the participants got to know one another. Then Camp director and plant conservationist Melissa Abdo gave an introductory presentation about bamboo. The best part of the day was the afternoon when founder John Hardy gave us a tour of the PT Bamboo Pure – the workshop and design studio. The design consultancy encourages farmers in Java to grow bamboo. Once harvested, they are brought here for treatment and processing. On inspection the suitable culms are split or kept whole or processed into planks or Silu (bamboo boards). These are then crafted into building components as required. The processing, crafting and designing at the same time, in the same space, fed into one another. The rejected bamboo is processed into bamboo charcoal and used in landscaping. John Hardy then showed us his latest experiments- a golf cart made out of bamboo and a bamboo sphere (that has a massage bed) that will be suspended in the middle of a stream. Day 2- The day started with a bamboo diversity walk. We walked around the campus to see clumps of different species and learnt about their uses. We then made a descriptive analysis of each plant so that we can identify them when we return to our respective countries. Later we were taken on a tour of the green school by Oren Hardy. He showed us around the different classrooms and administrative spaces and narrated their stories and the challenges they faced during its construction. We were able to see the evolution and refinement of building techniques from one building to another. In the afternoon we had another presentation about pests and pathogens and its treatment methods.

The day ended with a tour of the Green Village- a gated community of luxury bamboo homes designed by PT Bamboo. I was stunned speechless when we toured Sharma Spring a six storey bamboo house. It felt unimaginable that such a feat is possible using only bamboo and no concrete! Day 3 - The next day morning we met Ketut Sumerta (“Moko”) a Balinese craftsman with bamboo expertise. In his workshop we were taught basic bamboo structural principals. We then put theory into practice by building a scaled model of a bamboo house we individually designed. In the afternoon, we learnt to make splits and silu from the bamboo culm and make mats out of them.

Day 4 - The day started with us learning to make bamboo planks using sticks and splits. We then walked to the Green School to see and observe the principals we had learnt the previous day. In the afternoon we learnt the joinery techniques to assemble a chair. The experience was extremely humbling as our joints were nowhere close to the perfection the craftsmen can achieve within a few minutes. The day ended with an interesting discussion with Ar.Putra, a senior architect from PT Bamboo. We discussed possible fire retardant treatments, scientific studies and testing on joinery strength, and approval drawings for city councils.

Day 5 - On the last day, we attempted to make a mock up along with experienced craftsmen of a workshop space which is actually going to be built. We saw the application of all our learning over the past few days on site.

The experience in the Green School was eye opening. Not only did I learn about bamboo, but I also met people from diverse backgrounds. People involved in cultivation of bamboo, from government agencies, designers, artists, engineers, students, concerned individuals, teachers etc. It made me realise that the way forward is by networking - the coming together of like-minded people with the same pursuit and the need for multi-disciplinary interactions. I would like to thank the BERKELEY PRIZE travel fellowship for making this trip possible.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|