Delma Palma Travel Fellowship ReportItaly, May-June 2014

The ‘Great War’ is a benchmark. It has oftentimes even been perceived as barrier—an event that annihilated the status quo and propelled us into a new age. World War II impacted the fields of technology, architecture and urbanism so tremendously, that those ramifications are still felt today. We build in manner that attempts to take full advantage of technology at hand, engineering it for every tidbit of efficiency it can provide—mass production led to drone-like development where design lacked creativity, innovation, and even consciousness. The war not only affected these fields in the theoretical and academic sense, but also very significantly in the physical sense. Many built structures did not survive the impact of the greatest war the world had ever seen, but sadly added to the many casualties of war.

One of the places that suffered such loss, was Palermo. The area around Piazza Maggione, bombed during the Second World War—had not seen any reconstruction or renovations since. The area is a field reminiscent of what had once been there, with the foundation walls peeking out from under the field of grass. There have been several modernist proposals for intervention in the area but none have satisfied the needs of the community, who demand a historically conscious and contextual redesign. The BERKELEY PRIZE Travel Fellowship allowed me to join a team with the mission to give the city of Palermo a viable option for mending the hole in their urban fabric. For three weeks I joined a group of talented professors, architects, engineers, and students in designing what would become approximately twelve blocks of city fabric. We would be hosted by Italian architects. who would then organize a public presentation at the end of the three weeks. The presentation was to be held inside on the oldest palazzi in Palermo, adjacent to our site. Upon arrival to Palermo we were taken to a castle on a hill that would serve as our studio. The view from the studio was a reminder of how breathtaking a city on the water is—and how devastating a gap in the continuity of that city can truly be.

The first day we toured the site, walked all of Palermo—photographing, sketching, and discussing the history and potential of the area. Certain New Urbanist principles were established as guides for the design. Being onsite was very illustrative of the needs of the community. There was some sort of demonstration going on. There was live music and the space was ideal since there was plenty of room for the stage to be set up, for people, to collect, and much left over. The space was trying to be utilized but was by no means being stretched to it’s fullest potential. It was residual, filler space, in the center of a dense fabric, which just seemed torn within this neighborhood. We sat down to work—first deciding on the principles of design since we all came from diverse cultural, educational, and professional backgrounds. Regardless of background, there were some observations we all had made and agreed upon.

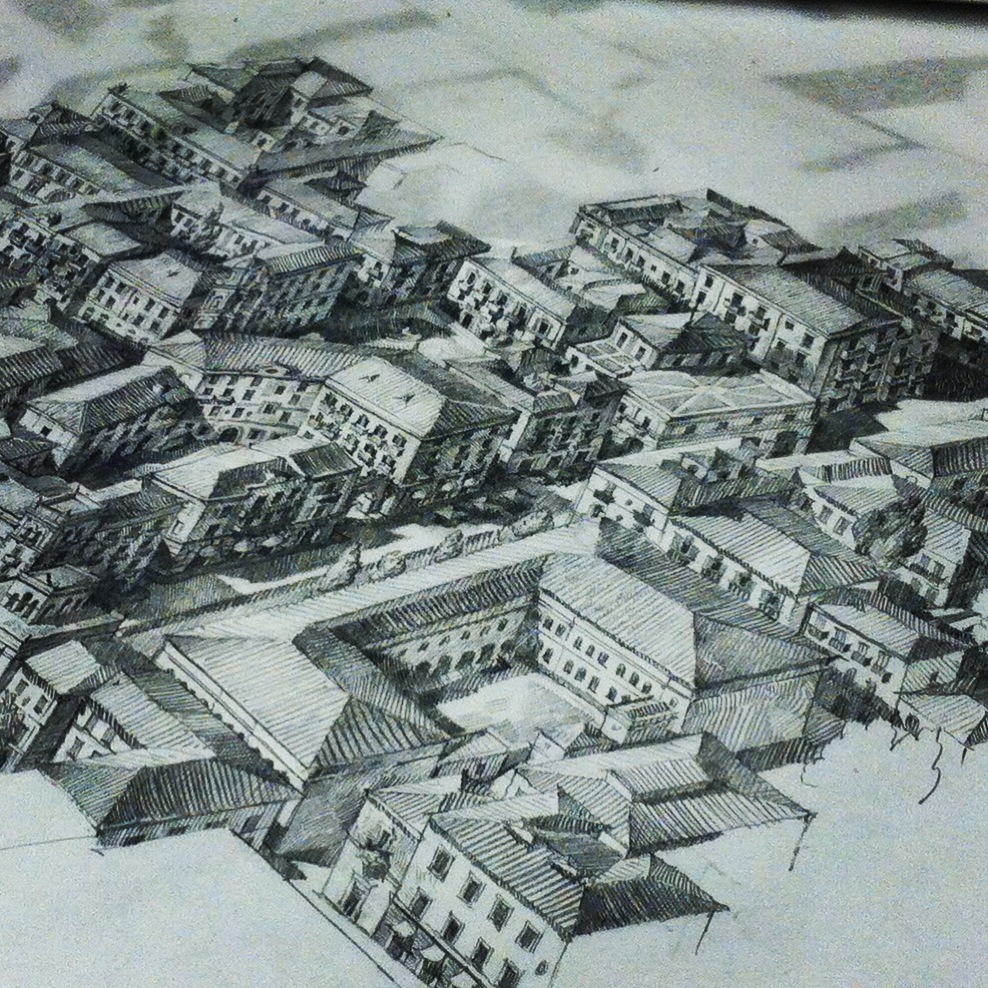

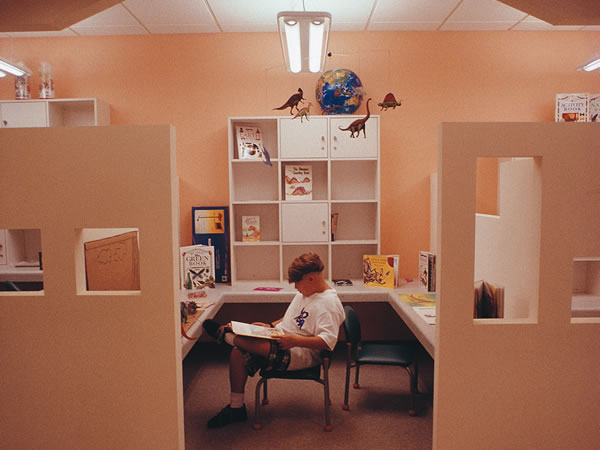

The principles were as follows: The existing streets would permeate the site through the proposed design—supplying a framework to follow that was already represented in the existing foundation walls. This would acknowledge and reestablish the past history of the site. The existing religious complex would be restored with an internal sport court (as soccer was noted as a popular pastime on site), and more dignified gathering areas would be designed for the sacred buildings in the area. Piazze would have definite hierarchy, and distinguishability in order to emulate the great and unique spaces that Palermo already has. Certain other needs of the community would be addressed through more public buildings in the program—a market building, a high school, and library. We worked for three weeks straight—8 AM to 8 PM, seven days a week. The studio consisted of finding resources (such as base maps and measurements), to sketching, drawing, and watercoloring. After studio we would dine together at Guisseppe’s (a local Palermitan restaurant) and walk about the city, discussing architecture, urbanism, and the city around us. By the end of the tree weeks we noticed even the smallest differences between Palermitan railings, brackets, and window surrounds. Since the way we perceived Palermo was through perspective, we decided our presentation to the community would mainly consist of two sequences of perspectives that would carry them through the urban plan. Each sequence would highlight the main spaces and buildings, guiding the viewer through a variety of urban cues.

Among our time in studio, we escaped various days to explore other cities and towns in Sicily. Through the analysis of cities like Trapani, Erice, Gangi, and Cefalu we were able to distinguish the successful parts of those Sicilian cities and have them inform our design for Piazza Maggione. We also encountered Sicilian festivals and celebration—that only confirmed the idea of how important public space is to the civic life of a community.

The team was comprised of two professors, three intern architects, one engineer, one graduate student, and three undergraduate students—from six different countries, including Italy, Ecuador, Russia, Honduras, Lebanon, and the US. The major benefit of coming from all over to design on the site was that the local politics did not affect our design, and therefore it could be received as an unbiased proposal for the betterment of the area. Meeting and working with Sasha and Olga (an architect and engineer from St. Petersburg, Russia), I was able to gain an insight into how the fields of architecture and urbanism are practiced in countries such as Russia. How the war affected them as well, and the trajectory of the architect. Classical architecture in Russia had acquired a sour taste because of the Soviet era—yet these two were among the few that still practiced traditional architecture. They traveled to Palermo specifically for the summer studio—as an exercise in traditional urbanism—so that they may take it back, and apply it, to Russia.

We also learned about interdisciplinary cooperation between professionals from a variety of office cultures—which at times led to difficulties in presenting a unified cohesive design. There were major differences in work ethic, design strategy and presentation style. Nevertheless, the presentation was a smooth compilation of all of these fountains of effort. The presentation to the community was truly an experience. We chose three people to present the design—one for the main principles and objectives, and one for each sequence of perspective views. Our Italian professor had his hands full translating from Russian, to English, to Italian, for the crowd. The audience was filled with mainly Italians (and a few other foreign) architects, students, and Palermitan people in general. Throughout the presentation, our audience seemed very receptive and compelled. Once we finished the presentation, we were bombarded with comments and questions—some difficult to answer, some critical, but mostly praise and admiration towards the renderings and effort put in throughout the past weeks. The public had, for once, encountered a proposal that could give them a vision for the future of that area—one that was respectful of the history and tradition, while still innovative and applicable. The Italian students were especially enthralled by our drawings because they had always been taught in school to negate traditional design—to plunge ahead toward the “progress” of modernism. Yet they could feel the energy in the room when we delivered a traditional urban plan. It excited people because it was sensible, harmonious, and beautiful. The conversation we exchanged with those students was perhaps the most valuable discussion of the whole trip. We were intensely exposing and defending a side of architecture and urbanism that they had been taught to deprecate—and even condemn. Speaking to colleagues of similar experience in the field was extremely educational for all of us.

The Berkeley Prize Travel Fellowship facilitated my trip and participation in the 2014 Palermo Summer Studio but it did much more than that. The summer studio had been the most comprehensive urban design project I had ever done in my educational career—as a graduate fresh out of college. I now work for a large architecture and urban design firm and realize just how much I learned through that small summer studio. The Berkeley Prize initially instigated my curiosity in how public space affects us and our wellbeing, then allowed me to exercise my knowledge in design to arrive at a feasible solution to a very real problem in the heart of Palermo. I believe (and have read material that supports it) that those three weeks have propelled Palermo into a mission for progress—to reconstruct the missing part of Piazza Maggione. To rebuild not only in a way that is beautiful, but also conscious—of history, of its people, and of the future users of that public space. Information about the 2014 Palermo Summer Studio Project: http://www.blogtaormina.it/2014/06/23/ri-generazione-urbana-palermo/185029

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|