Mandy Oeni Travel Fellowship ReportCITY OBSERVATIONS ON ACCESSIBILITY, AND PARTICIPATORY DESIGN EXHIBITIONS: FIGMENT (NEW YORK) | SPONTANEOUS INTERVENTIONS (CHICAGO), JUNE 6 – JUNE 28 As I write, a stranger in foreign land, my musings represent the voice of the ‘other’ - the unfamiliar person whose habits are not accustomed to the daily rhythms of the routines of the local community. The French have a word for such feelings that emerge, dépaysement, to describe the uncertainty that comes from travelling, of being a foreigner somewhat displaced from your origin. Having found myself in unknown territory, I am but one of many others who are as disoriented in their physical environment, which helped me to observe the little oddities of spatial experiences that remain unnoticed by those who are used to the way of life in the city. Yet, my travels speak only for a slender portion of what constitutes the ‘others’ in society, those whom universal design should fully embrace. Travelling from my home country to the United States has allowed me to see the accessibility of cities in relativity. The beauty of learning through this journey comes from being able to understand each city by measuring it as a yardstick against others, New York alongside Chicago, as well as in comparison to where I come from, Singapore. The notes that I have made from this overseas stint have allowed me not only to see the effectiveness of universal design applied in these developed cities, but also to appreciate the valuable design interventions in my home country that have made it more accessible. In modern urban environments where living, working, and playing have been subdivided into different planned zones of a region, we are no longer confined to the comforts of our neighbourhood, and a majority of the population commute daily back and forth from their residences to workplaces, and so on and so forth. It becomes natural then that the most telling nature of accessibility should start from its public transportation systems. My observations of the city therefore began from living out my stay through the most basic form of a local resident’s routine, the humdrum of taking subway trains to get around the city, and examining the ease of which this could be practised.

Upon arriving in New York, I initially tried to get from place to place based on intuition and by following maps and directional signs at the station, without any form of pre-planning. Truth be told, I actually ended up having to make detours, as I boarded the wrong train to my destination. I realised that even for me, a person without any disabilities or difficulties reading the signs in English, it could be frustrating to grasp the system of train routes and schedules for the purposes of way-finding. Firstly, the signs located at the subway entrances and platforms that indicated the direction of the trains running generally did not refer to the name of the place that was the end destination or interchange, but instead were labelled ‘Uptown’ or ‘Downtown’. So one always had to be aware of the current location of the station, in relation to the other destination, and whether the train to be boarded should be north or south bound. This is not immediately apparent to people who are just getting acquainted with the city, or those that are less fluent in the English language. Additionally, maps had to be read and understood in order to ascertain the sense of direction. Furthermore, due to the extensive connectivity of the rail network, each coloured subway line had several numbered trains that ran along the same path, but differed from each other through ‘express’ or ‘local’ routes. One had to be especially aware whether the express train would stop at the destination stop in mind, or not. As the same platform served both types of trains, extra attention needed to be given to ensure one was boarding the correct train. Quite frequently, service disruptions would happen on certain days and times of the week, so certain numbered trains would not be running. Notices would be put up to notify commuters of the specific dates this would occur, with instructions on how to get to the affected stations. Again, this is not immediately clear, and closer reading would be required to figure out which trains should be taken. The metro system definitely proved to be a confusing experience for the uninitiated like me, and I found walking through the city’s number-gridded streets much easier for navigation. In contrast, Chicago’s subway system did not need much getting used to, as the network was less complex and more straightforward. The urban layout of the city was clear-cut, as the city’s activities were concentrated in the downtown area called the ‘Loop’. Therefore, as its name suggests, the trains ran from the outlying districts towards the city centre, and back out again. The loop therefore serves as the heart of Chicago, and it was less difficult to figure out directions just by reading the maps and signs at the stations. Train lines were distinctly colour-coded, and one simply had to use the Loop as the focal point to know which train route to take. On board the metro train, announcements were also constantly being made to inform passengers if the train would be skipping certain stops, and to notify them beforehand on which side the door would be opening at the next station. This allowed ample time for less abled passengers to prepare to exit the train, without worrying about rushing out once the train arrived at the next station. The use of both visual and audio aids in the train cars definitely made commuting less of a hassle, and I barely got lost, even during the times I travelled out of the Loop to other suburban regions. Nevertheless, after numerous train rides and many staircases painstakingly climbed at the subway stations, I realised that in many of these public transport stations, I rarely took the elevators as they were mainly relegated to a corner of the platform. Perhaps it was the old age of these stations, having been developed at a time when accessibility was less of a pressing issue, leading to the lack of attention in the design of these basic facilities. It dawned upon me that comparatively, the city in which I live in had fittingly well-designed accessible underground train stations that seamlessly connect the pedestrian to the subway system in a more pleasant experience. One of the more prominent stations back home which came to my mind is the design of the Bras Basah Station, which is the deepest underground platform at 35m below ground. The passenger travels from the ground level down to the platform level via long escalators that run under glass panels supporting a reflective pool of water. The ambient daylight streaming through the surface of skylights therefore creates a special transitional experience that greatly emphasises how accessible spaces can be designed beautifully. On ground, however, one of the distinctive accessibility features of New York City is surely its bike-

sharing system owned by CitiBike. Based on population and transit needs, and via a public input process, hundreds of bike stations were set up all around the city to establish this simple structure of bicycle rental points. The kiosks provide bicycles for quick rental services that allow riders to use bikes from any docking location, and return them at any of the other posts across the city. This convenience is further enhanced by the widespread network of bike lanes between blocks and greenways through parks and the like. The comprehensive cycle path system is a step forward in aiding social inclusion, where in wealthy cities, predominant groups of people such as children, youth and the elderly are drastically restricted in their mobility because the city is designed for cars – a means of transportation that they cannot use, or afford. Improving street conditions for pedestrians and cyclists enables a lot more people to get from one place to another with better ease of access. A bicycle strategy that is supported by and built up around an effective public transport network is therefore a humanistic, people-friendly approach to creating an accessible city where mobility is possible for all. Apart from the daily travel journeys, one of my favourite accessible places in NYC is the Chelsea Highline. This disused old railway track has been adapted for reuse into a converted public park that is elevated from the street level.

Several elevators lead up to this linear park connector, and the greenery provides a brief respite from the hustle and bustle of the busy streets and avenues. Even for ordinary pedestrians it is a pleasant escape from the frustrations of traffic light junctions every 100m block. Although the park is directional, the pace of pedestrians slows down here, with the presence of many lawns and benches that encourage rest. Those who are disabled would thus feel less harried by journeying through this elevated ‘street’, and are even granted beautiful views of flora and the unique skyline of Chelsea which features famous architectural buildings. The park also integrates a ‘gallery’ area as seen above, with ramps and stairs integrated with seating to provide a view over the passing cars of the road below. This basic viewing space is truly designed for the public as one can observe diverse groups of people gathering here, with no exclusion over any particular group of visitors. The park is also home to a myriad of sights, smells and sounds - the company of buskers, commissioned artworks, food vendors, the scent of flowers, and decked with the textured surface of wood, so that one is constantly walking through a sensorial experience. With a continuous edge of greenery lining the sides of the railings, wheelchair users have a change of sight through the delicate design of the surrounding scenery. Hence, the space is interestingly well-designed to incorporate such universal elements that make it an accessible park that is inclusive, despite the site being put on a pedestal above the common plane of pedestrians. FIGMENT New York (7th, 8th, 9th June) After arriving in NYC on the 6th of June, I got myself somewhat acquainted with the City, before getting a night’s rest from the long-haul flight. The next day was an early start for me, as I had signed up for a morning shift to help build the pavilion in time for the opening of the FIGMENT participatory arts festival the next day. My time volunteering was well-spent working with designers, students and other volunteers to erect the Head in the Clouds Pavilion on Governor’s Island. It was pouring pretty heavily that day (as well as the many days that followed), but it was heartening to see the architects themselves working non-stop to assemble the structure on site. I had the privilege of working directly with the designer Jason Klimoski, from Studio Klimoski Chang Architects (studioKCA), and witness the cloud taking form from the many bottled ‘pillows’. The total amount of bottles used to construct the space represents the amount of plastic bottles discarded in NYC per hour. The project therefore collected recycled bottles from various organisations and communities, and then translates the final product as a gathering space for visitors of the FIGMENT festival. When I visited the pavilion during the opening weekend of the participatory arts festival, the space was nicely finished with ambient daylight, and a resident DJ that allowed for people to mingle and enjoy the various interactions within the space.

Apart from the main City of Dreams pavilion at the festival, there were many other independent artists that set up artworks that greatly involved the participation from the public. In one place, it was apparent how art could be accessible to people of all ages, and bring together a community through fun and enjoyment. Even while queuing for the ferry to the island, a separate line was formed for families with prams, or the disabled on wheelchairs, and they were allowed to board the ferry first. The detail that went into the planning and execution of this event underscores a particular sensitivity towards catering to the needs of all people, regardless of age or ability. On the island proper, there was a diverse range of activities that allowed kids, adults and elderly to interact with the sculptures. The senses were also engaged through paint, kinetic activities and sound sculptures to create a holistic experience of art. A hopscotch path was drawn with chalk on the roads in order to make the act of walking enjoyable and appealing, especially to children. Families could be seen picnicking on the lawn, and there were even mascots and costumed characters that walked around to get everyone participating. It is this sort of ground-up initiative that I find particularly relevant to the accessible city – with a rise in public activities that engage a multiplicity of interactions, and incorporating this level of inclusiveness, which is certainly a step further in achieving the standard of universal design.

Spontaneous Interventions: Design Actions for the Common Good

Due to bad weather conditions, my original flight to Chicago got cancelled, and the earliest domestic flight the airline carrier could reschedule me on was for the weekend. I ended up staying in Chicago only for a week, and missed out on some of the events lined up earlier in the week as part of the Spontaneous Interventions summer-long exhibition. Nonetheless, the set-up was very informative, and presented a collage of community projects that sought to solve some of the city’s urban problems. The schemes were exhibited on banners that could be pulled down for easier reference, and colour-coded according to their relevance to a few categories: information, accessibility, community, economy, sustainability, and pleasure. It was an interesting layout that allowed the viewer to match the banner with squares on the wall that labelled the urban problem, and when the banner was pulled down to be read, the pulley system would lift the square plate to reveal the ‘intervention’ that was made by the community. A recurring theme among most of the projects was accessibility, of which a huge portion is associated with information based systems, and solutions which tap on the functions of smartphones and software. Most of the projects are small-scale schemes that attempt to change the level of accessibility through the scope of the neighbourhood. For example, a specific project in Los Angeles proposes turning traffic signposts into urban furniture in order to forge a sense of ownership among pedestrians. To counter the ubiquity of streets that are designed for cars rather than pedestrian experiences, the designers

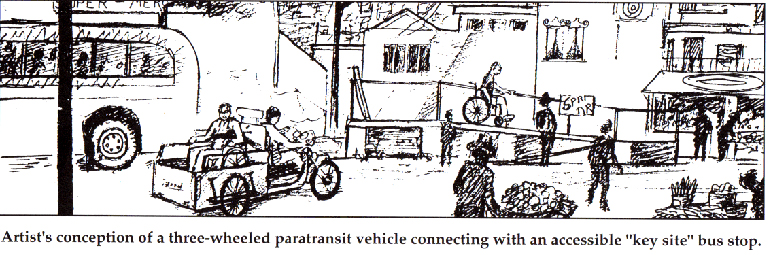

hoped to appropriate universal traffic signposts to make sidewalks inviting and comfortable again for the pedestrian. This therefore represents a shift towards public awareness that calls for urban design to be more accessible across all groups, rather than being automobile-centric. With an informal exhibition setting that places box-stools around videos, books, as well as infographic posters, the environment encourages us to start conversations about what can be done to improve our neighbourhoods. The exhibition succeeds in this way, as community design should be encouraged for the public to take ownership of their spaces, such that effective dialogues can be initiated to resolve the basic problems of accessibility at the immediate level of the neighbourhood. Travelling though two very developed cities has taught me that the more we build our cities around the way cars move, the further away we are from achieving the effectiveness of an accessible city. Essentially, the accessible city is one that is anthropocentric; we need to start designing for the needs of humans in mind, in order to comprehend the challenges of the disabled in society. Increasingly, I can see a movement towards a more pedestrian and bike-friendly environment in both cities (whether in the establishment of bike lanes, or guerrilla community interventions that spark a public awareness), and urban planners should work with the local government to continue to make this a sustained effort. If we attain satisfactory standards for mobility in the design of our cities, we can start to move forth with ensuring the needs of the less abled are met. Ultimately, a vision for designing for all should inspire us as future architects to incorporate different layers of multiplicity that integrates society in an inclusive way.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|

.jpg)