Malvika Mehta Travel Fellowship ReportSpain and France, June 26th - July 1st 2014

This opportunity has also been an ideal learning experience because I was able to study accessibility in the context of a variety of spatial scales, and observe many interpretations of universal design. My learning was mostly informal, but the travel has given me much to mull over- I can see my own reflections mature over the last month since I have returned. These 5 exhilarating weeks of travel are hard to sum up in a report! Below I revisit some highlights of my travel: Avila

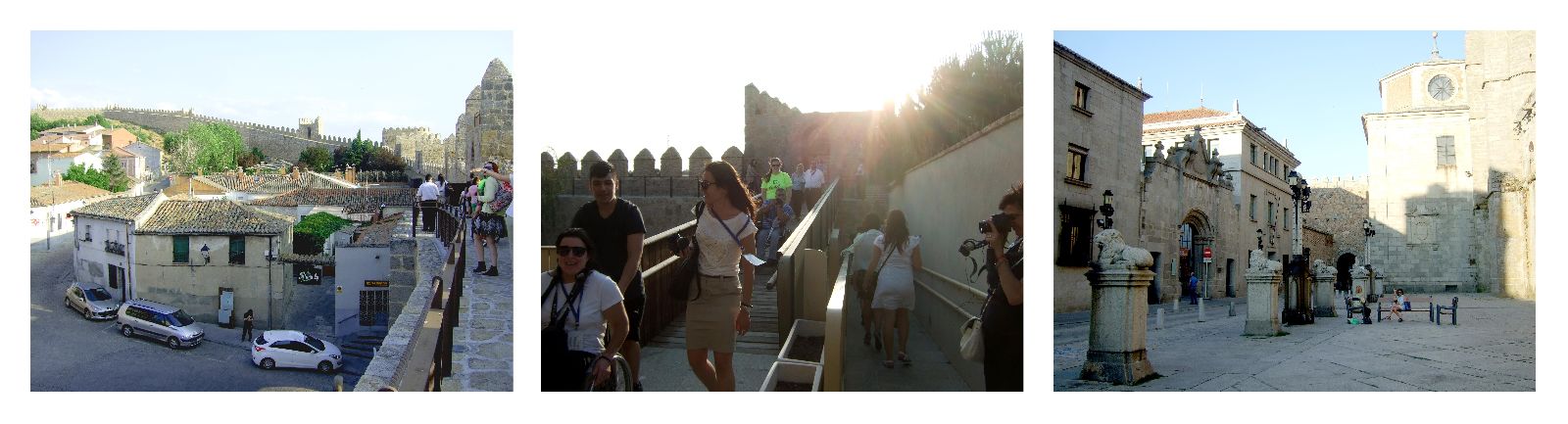

On 25th June I arrived in Spain by flight, stopping over for six hours at Zurich, Switzerland. I was immediately struck by the vast difference between the European cityscape and the Indian- they seemed like different planets! From the Madrid airport, a commuter train dropped me off, two hours later at the city of Avila, which hosted the ‘IV International Congress of Tourism for All’ from 26th to 28th June. The venue of the Congress was carefully chosen. The City of Ávila was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1985. And to better that, Ávila, won the first EU Access City Award in 2010 (illustration1). This was particularly exciting for me- creating accessibility to architectural heritage, also as a route to urban renewal was a theme we pursued in this year’s essay submission (co-authored with my friend, Joyjeet Kanungo). Not only has the city sensitively adapted and preserved its medieval city walls, and the many medieval heritage sites, but accessible tourism has become an important component of its economy. The ‘IV International Congress of Tourism for All’ scheduled is organized every three years by The ONCE Foundation in conjunction with ENAT (European Network for Accessible Tourism) with a focus on imbibing the values of universal design to enhance and enrich the tourism sector. “Accessible Tourism” broadly stands for tourism and travel that is accessible to all people, with disabilities or not. This year the Congress was conducted at the Lienzo Norte Conference and Exhibition Centre in Avila. As a student, being in this world of professionals discussing that status of universal accessibility in their country or city was all the more rewarding. One realizes that while there were cities where not enough thought is given to creation of accessible environments (such as Delhi) there are cities where living and travelling for everyone is an equally seamless and enjoyable experience. The Congress was a celebration of all that that has been done around the world to create universally accessible spaces and cities. Experience and information was shared by professionals in the workshops, round tables and plenary sessions through the two and a half day event with an audience composed of more than 150 delegates from around 20 countries. A range of fields and stakeholders were represented- architecture, city councils and other administrative bodies, tourism professionals, NGOs, researchers and so on. The lunch and tea breaks gave the delegates to interact and network with each other. I too met many interesting people in these breaks who were happy to share their experiences with a student of architecture from India! Particular presentations stood out. For example, Ms. Fionnuala Rogerson, Ireland, Director of the International Union of Architects' Architecture for All ", Ireland made a presentation titled "Strategic Planning in Heritage Accessibility". In her crisp and graphic presentation- she left the audience with a series of thought provoking questions to ask themselves, and find these answers for their countries and cities- about standardisation of design, the use of technology to create access as done in the Institute of Engineers, London, compromising or entirely losing the essence of the architectural experience to achieve accessibility, permanent or temporary interventions, and the action cost- feasibility and impact of creating accessible spaces. Another presentation pursued a different line of thought- how nature deals with accessibility. Delegates also heard about improving access to the Acropolis and the historic centre of Athens, to the Iguazu natural park, Argentina, to urban parks and historic gardens in Madrid, to museums from Germany, Spain and Australia and labour integration of people with disabilities and the economic opportunity presented by accessible tourism. Many architects discussed how funding and budgetary restrictions are a ubiquitous hurdle faced in the creation of accessible spaces. There were also some stalls at the venue, where the latest in technological innovation was on display, a lot of which was mobility related. There was also an audio guide to enjoy a painting, designed especially for the blind (illustration 2).

On the evening of the June 26th, the participants were given a guided tour of the city of Avila. Being in a group of accessibility experts as well as individuals with different abilities, Avila was critically appreciated as an accessible environment. Our visit began at the Avila Tourist Information centre, which housed a tactile museum that held miniature three dimensional reproductions of the city’s most important sites. This was my first experience at a tactile museum. Again I was reminded how easily accessible information is a delight and of value even to those with no apparent disabilities (illustration 2). The next evening a walk to the walls of the city was organised. Avila is known for its largely intact medieval fortifications. Only one section of the walls was adapted for wheelchair accessibility. Earlier in the day I had climbed up the other section of the walls and now put together I could compare the experience (illustration 1). These three days in the small city of Avila, whose motto is "A City for Everyone" was a great kickstart to this trip. Madrid, Barcelona

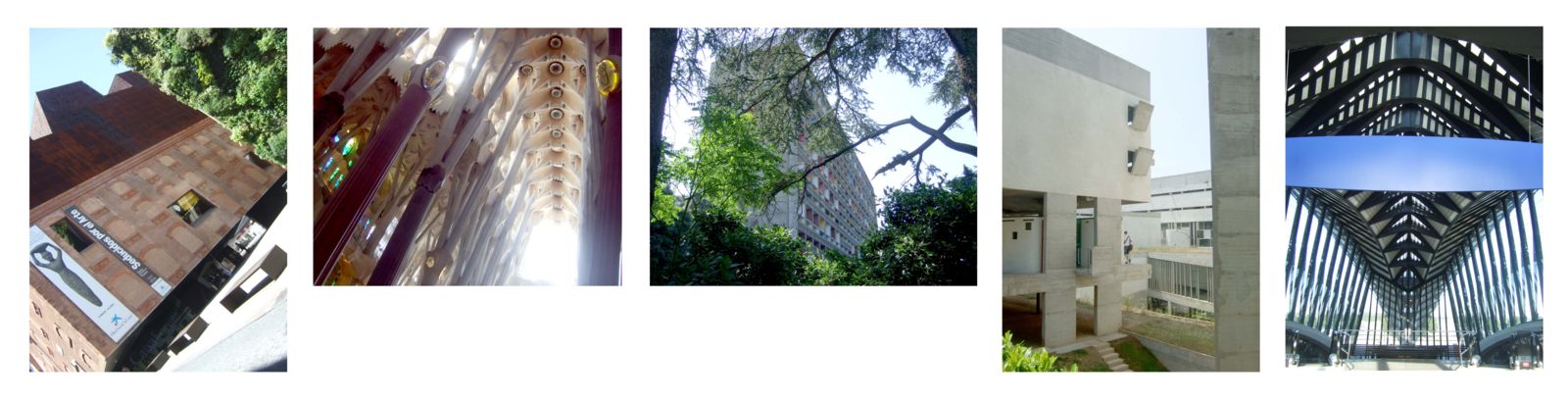

In my mind, I imagine my whole journey to Europe as a string of these awe inspiring moments where I stand in the environs of breath taking architecture, simultaneously trying to make sense of the spatial experience and marvelling at the genius behind its creation. I seized this opportunity to explore Madrid and Barcelona in Spain. These cities with their rich architectural heritage, juxtaposed with bold contemporary expression create intense and inspiring urban spaces (illustration 3). I also spent a great deal of time inside museums and galleries viewing the works of art that the cities offered on display. Nantes

On July 7th I arrived in France by plane, admiring the views of the lush western French countryside. Nantes, the capital of Brittany, was settled in roughly 70 BC and flourished as the foremost French port, known for its notorious slave-trade. When its ship building industry was relocated outside the city, Nantes transformed into a thriving student and cultural nucleus. Navigating around Nantes on foot was enjoyable and easy, as one would expect of a city awarded the prestigious “Access City Award” 2012. Nantes comes in second place in the European rankings, behind Berlin. Not only physical access but access to information in the city was easy and thoughtful. I could clearly see how the ideal of universal accessibility had driven the design and detail of streets and public spaces but how it positively affected the experience for everyone (illustration 4). The history museum of the city is housed in the castle (illustration 4). The castle itself is beautiful and what made the experience even more exquisite is the approach adopted by the architects to create universal access in this heritage building, making it a seamless and respectable experience. The access retrofits were bold and held their own, glorifying the ideals of universal design. Information was also creatively shared through graphic story -telling and was aided by tactile and braille panels as well as a sign language expert (illustration 5). I was also thrilled to visit the Maison Radieuse (The Radiant City) in Reze near Nantes, one of Le Corbusier’s early social housing projects completed in 1955 that was a pure embodiment of his principles (illustration 3). Lyon

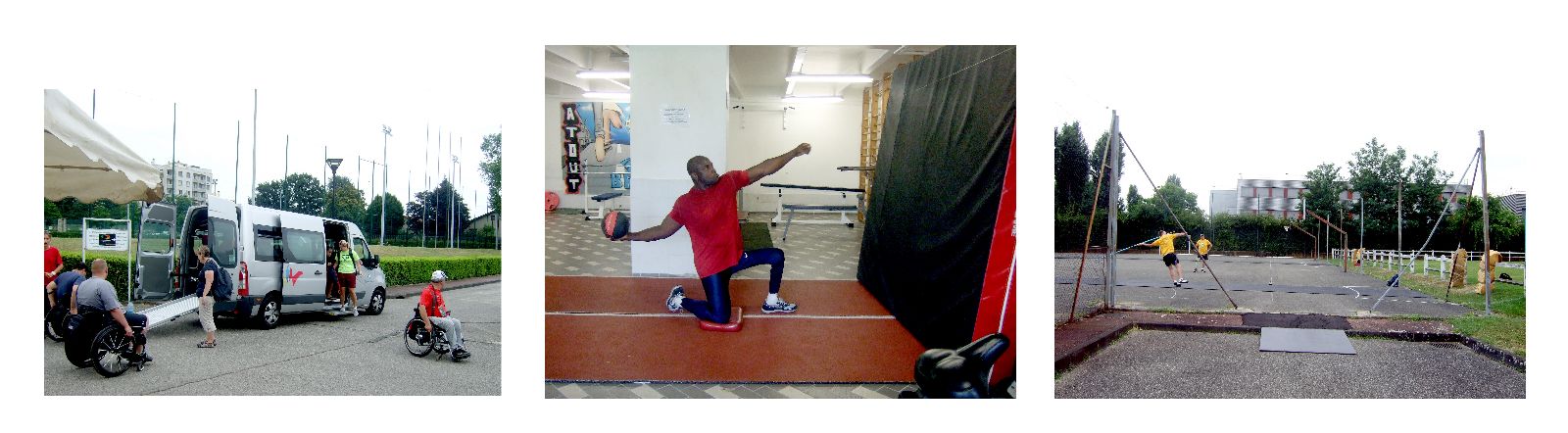

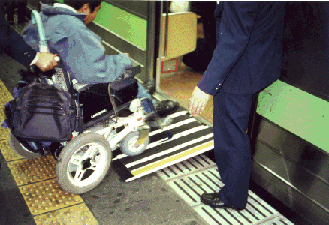

The Paralympic Games, held in Lyon, was definitely the highlight of my trip and the most unique experience. Finally to settle down, at least temporarily, in one place after being on the road for almost fifteen days was a relief in itself! Moreover, being in Lyon for three weeks, allowed me the time to really get comfortable in the city in the rhythm of the city. I almost forgot I was a foreigner to the city as I sunk into the routine of a volunteer at the Games. Experiencing the life in a foreign city is in itself a new and unforgettable experience. As a student of architecture, the Games really gave me the time to observe and reflect about shaping of urban experiences. I arrived in the city of lights as Lyon if often called,on July 12th, though the Games were to begin only a week later. On 13th July, after registration, I headed up to ‘the volunteer tent’. The Games were organized on an undulating grassy ground on the edge of the city of Lyon, called Parc de Parilly (illustration 6). Large tents were assembled on site, each dedicated to a specific function. Rubber matting was laid on the ground for ease of access. Dry toilets were placed all over the site. Additional wings or tribunals were set up to seat the spectators as the biggest turnout in the history of the Games was expected. One tribunal was set up especially for wheelchair users, complete with user friendly access route (illustration 8). The function and management of the whole event rested on the shoulders of over a thousand volunteers, many of whom had been engaged in this project since six months.

I took the time to explore this city of lights as Lyon is known. The city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site (illustration 7). Its Roman and Gallic remains are testimony to this two thousand year old city. I spent an entire day exploring the city on cycle- a completely novel experience for me. In Delhi, where I live, it is uncommon and unpleasant to use a cycle as a means of transport if other modes of transport are available and can be afforded. In Lyon I was absolutely thrilled to cycle with a purpose! I also visited the ‘Cite International’, conceived by Renzo Piano. One of Buckminster Fuller’s early study models for a geodesic dome was on display at the contemporary art museum there (illustration 7).

About thirty away minutes by train followed by a thirty minute trek, lies the La Tourette Monastry, also designed by Le Corbusier. Visiting this spiritual building was one more of those uplifting moments that made this trip so special. Experiencing in real, a building that one has read and seen so much about, is truly dreamlike! (illustration 3). The opening ceremony was held on the evening of 19th July. There was a lot of cheering and positive energy in spite of the rain. This was the biggest event of its kind- 1,100 athletes from 85 countries were set to compete in 207 medal events and media and broadcasters from 25 countries were present to provide coverage. Lyon with its population of 720,890 and area of only 47.95 km², is a small European city and an extremely small city for a resident of Delhi! The whole city was energized. 25 hotels across the city were booked for the athletes, the media and the officials associated with the event. One could always spot the red volunteer jerseys and the colourful gear bearing the symbols of each country, among the crowds in downtown Lyon. There were many components of this experience that I have brought back with me. One of them was watching the actual events as the athletes compete. The events are categorized according to the disability level of the sportspersons. One of the events which particularly impacted me was the long jump competition for T12 category, or the blind athletes. The athletes depend on their sense of sound and of course muscle memory acquired through rigorous practice, to calculate the run up distance and make the jump at the right moment in the correct direction, upon the audio signal from his/her guide. Every now and then, an athlete would trip over or jump outside the pit but never walk back without a smile. Their spirit was admirable! Another high point was the recreation ‘Village’ at the Games’ venue. The Village offered one and all a glimpse into the everyday life of a physically challenged individual. For example, one could try a ride on a two-seater tandem bicycle, a ‘trike’ (a tricycle) or a ‘hand crank’ (a three wheeled cycle operated by arms). The tandem bicycle, where my friend and I could co-ordinate through sight and speech is actually designed for a partially sighted or blind user to cycle with a sighted partner. Seemingly minor details really struck me- for instance, how does the blind person actually mount a bike (illustration 8)? One could also try to use a wheelchair and navigate through doorways and different kinds of ramps, play basketball and compete in the boxing rink on the wheelchair. I had not realised the sheer amount of arm strength required to move a mechanical wheelchair. Recreation for some, but these visits to the village really impacted me, filling me with a sense of urgency. I was reminded once again of how fundamentally a sensitive design can guide/ alter our experience of and in the external environment.

Especially when dealing with accessible environments, the details- the precise measurement and turn of angle become so important. On the other hand, no design really has integrity unless guided toward an overarching vision- the obvious absence of this in the case of the accommodation Unfortunately my lack of fluency in French allowed me only a limited choice of volunteering jobs. I chose to work with the media and my main role was to spend about two to three hours each day cropping the live feed into smaller event videos. This job fit me well because I spent a lot of time watching and observing athletic events on camera and still leaving plenty of time to explore the camp in person. I took some time to visit all the other spaces associated with the Games. I visited the Bron stadium, practice facility for all the athletes where the layer of retrofits was easily decipherable (Illustration 9).

I also visited a couple of hotels, where upon speaking to the athletes and their accompanying staff. Overall, the idea of accessibility is often imagined as an extra layer of retrofits such as elevator and not as much an experiential design. For instance there is a vertical stack of rooms that is only one room on each floor of the hotel, which have been designed for wheelchair movement. In the case of the Paralympians, these were not truly usable as they were travelling as a group and naturally preferred to be situated close to each other, on the same floor. In another hotel for example, where the British team was put up, there is an elevator to carry the guests to their rooms above, the lobby area of the hotel is also reasonably comfortable, but there was one gaping flaw- the gymnasium and swimming pool in the basement required the user to step down twice from the lift lobby. I got the good chance to speak to the team nurse. She too was saddened over ‘how the thought process just did not exist in the designer.’ The accessibility requirements of different users were considered in terms of some basic facilities, such as elevators but not as a holistic spatial experience. At the end of the five weeks, I boarded the expressway to the airport with a heavy heart. And imagine my surprise when I suddenly found myself in the famed and stunning entrance to airport terminal designed by Santiago Calatrava (illustration 3)! It was a wonderful parting gift! Being a Berkeley Travel Fellow was an extraordinary experience as it gave me the opportunity to experience and observe the social dimensions of architecture in a variety of settings. [References] http://www.accessibletourism.org http://ec.europa.eu/justice/discrimination/disabilities/award/index_en.htm

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|