Disha Sahu Travel Fellowship Report19 YTK / IFHP Urban Planning and Design Summer School 2013- Helsinki, Finland. August 11th- August 25th, 2013.Greetings from the Scandinavia !!!Part 1: Learning from Helsinki This year's Essay Question asked us to "....provide an overview of what is being done your city to make it accessible to people who have physical disabilities. And what more can be done in your opinion as an architect ? "

The idea that I developed was ' integrated inclusiveness- the requisite for accessibility',- a system where there is an inherent micro scaled detailed inclusiveness and a seamless vertical integration between various modes of urban transit to achieve first and last mile connectivity. And travelling to Helsinki made me aware of how this integrated inclusiveness can be achieved in a manner that is rooted in its context, culture and people. Walkability being a core agenda- I decided to tread down the whole city by foot and, only if needed, use public transport (city bus or tram). Navigating the city, I noticed the extensive infrastructure- from sidewalks complete with textured tactile trail, pedestrian crossings, biking lanes, an optimum balance of soft-scape and hardscape, visual and leisure corridors, multi-modal transit, multi-use city blocks, routes of movement and nodes of transition as active public spaces - these, I believe, are critical ideas which form a structure for accessible and walkable cities. The systematic detailing of materials, texture and signage on the streets of Helsinki not only makes walking an enriching experience but also advocates for walkable, sustainable and accessible cities. In the Scandinavian context, places where demographics and densities are rather low, making public spaces walkable, liveable and accessible is crucial to rendering them public places. And Helsinki has been successful in achieving it.

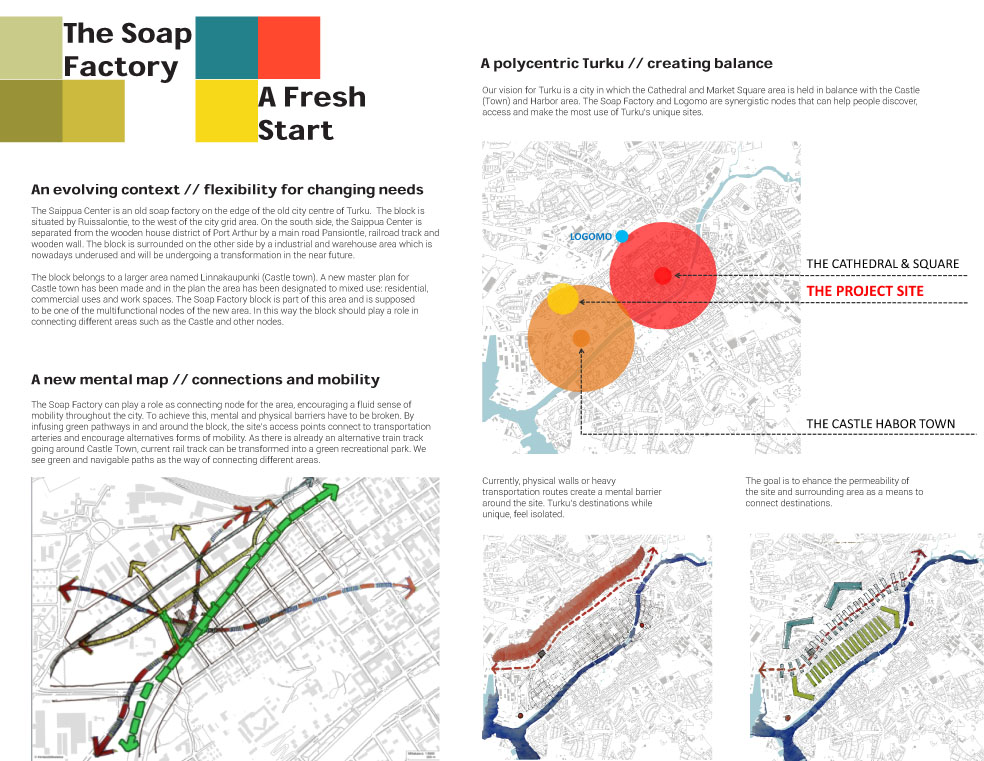

The success of such a systematic and well functioning infrastructure belongs to the fact that Scandinavian countries function on a welfare state model. Thus, the government is fully equipped and entitled to provide for all necessities of living towards its citizens. A unanimous ownership makes projection of urbanity and implementation rather sorted and meticulously executed deeds. Stable economics backed by moderate population further ensures that the ground results are achieved. But the system has its own set of flaws. Being a welfare state, the scheme is extremely paternalistic in its outlook. Thus there is a "everything looks same" phenomenon. Highly ordered and sometimes mundane, this urbanity lacks human energy and does not reflect sufficiently on the aspiration of people. Asian cities which thrive on a collage like character and are brimming with human energy are enigmatically more inviting and thus (conceptually) more accessible. And therefore now I imagine, the ideal condition of accessible environment really lies somewhere in between. Sufficiently supported with physical infrastructure at the same time brimming with inviting character and human warmth. Part 2: The Summer School Task - REDESIGNING THE 21 st CENTURY URBAN BLOCK As a part of the Urban Design Summer School at Aalto University, we were asked to analyse a former soap factory (Saipuaa Centre) site located right at the edge of the city centre in Turku, Finland. This site borders between a historic, residential city centre and a former industrial area. The task was to create a conceptual framework and a plan for the soap factory area (geographical area = 4500 sqm) with an understanding of multi-faceted nature of urban development.

Proposal (excerpts from the final design proposal as a part of submittal at summer school) Introduction Due to the dynamic nature of society, the ways in which people navigate, inhabit and activate places; cities change over time. Certain areas become more or less attractive with time, urban order and function. The built and natural environments evolve. Population increases and user needs diversify. Urban blocks can have many different functions over time and therefore may cater to global or local levels of urbanity. Historic cities such as Turku also contain industrial areas that have lost their main functions as the economy shifts and often face the challenge of adapting to the needs of 21st century society. What kind of built environment is most suitable for an evolving socioeconomic and cultural locale? How can design interventions enhance the functionality and vibrancy of today’s society? We propose that a key element is flexibility and accessibility given today’s evolving world.

A chance to create dynamic urban public space The opportunity to revisit the Soap Factory is not merely a chance to enhance a set of buildings. It is moreover an opportunity to envision what a dynamic urban block may achieve. Turku’s unique character as a historic, economic and cultural hub yields an interesting example of urban polycentricity. Potential exists for the soap factory to become a substantial node in the city. By infusing flexible, accessible and inviting spaces into the urban landscape, we envision a fresh start at a local scale that can in turn create a more balanced and connected Turku. A Vision for the Site Area: A New Mental Map

The block is situated by Ruissalontie, to the west of the city grid area. On the south side the Soap is separated from the wooden house district of Port Arthur by a main road Pansiontle, railroad track and wooden wall. In analysing the site, the authors identified current navigational paths between the site, its surrounding area and beyond. The authors then proceeded to identify potential new paths that may offer comfortable and easy connections between the site and Turku’s other destinations. In this project, the authors see the Pansiontle railway track as a physical and mental barrier, but also as a connecting element since the road connects the Soap Factory (area) to the suburbs of Turku. Such broader connections are captured by the red and blue arrows, which mark the potential mental pathways that could seamlessly link the new developments with older established destination areas. The Soap Factory can play a role as connecting node for the area, especially given the significant master plan and transportation plan for the area. As previously mentioned, the current master plan for the area intends to create a balanced mix of housing that could cater to a wider demographic range. Yet despite such intents, the resulting mix of users is ultimately unpredictable and likely to evolve. Similarly, the transportation plan for the area includes the introduction of light rail near the site as well as an eventual rerouting of the railway (Keskikastari, 2013). Such plans may infuse an unpredictable mix of users and modes of transportation. The breakdown of mental barriers may be achieved organically through the changes in transportation modes and the influx of a more diverse local population. To support such changes and the ultimate goal of created a more connected Turku, the authors suggest the implementation of green and navigable paths. The current track could be transformed into a green recreational park, taking inspiration from New York’s high line depicted in the photos below. Such transformations could enhance the aesthetic and sensory quality of connections within the city that in turn yield a more balanced city where people can walk and linger in a greener environment.

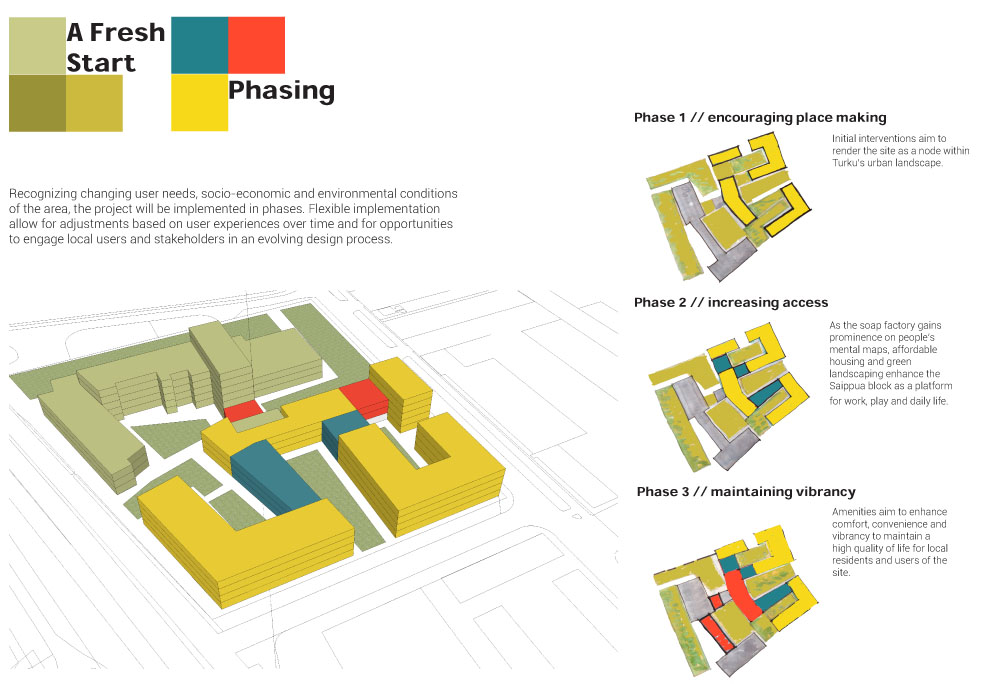

As a vision for the Soap Factory, the authors wish make a fresh start for the area while linking to Turku’s historic past. The vision for the Soap Factory is built up around 3 key concepts: accessibility, flexibility and inviting. Accessible The Soap Factory’s urban block must be designed in a way that it accommodates people of all ages and abilities. We want the block to be a connecting node in a network of nodes such as LOGOMO and other nodes in Turku. Furthermore, the block must be accessible from different sides and must attract people from different direction. We want to achieve this by creating sightlines that showcase people an activity inside the block. Flexible To be able to adapt to evolving needs of a range of users, the authors’ vision also centres on the notion of flexible space. As a general principle, flexibility will be built into any renovations of the buildings so that user can alter the spaces according to temporal needs. For example, living spaces could be condensed to give way to pop up work spaces while common areas could be made through malleable interiors. Flexible structures would also cater to evolving modes of transportation, hopefully moving away from car culture to that of shared bike schemes or communal gardens. For example, the authors have conceived of a flexible metal structure for in the heart of the block. This structure can have different uses over time such as parking, working, living etc. In this way the concept encourages mixed and dynamic use. Inviting To attract people to the Soap Factory’s block, it must be an inviting place. Engaging design should foster collaboration and user agency. By creating meeting places and having group activities for different seasons, the authors want to create a lively environment. One way of attracting people is by opening a market at one of the main entrances of the Soap Factory, enticing people into the urban block to explore the inner square where a mix of uses meet. Around the inner square would also be a café, communal spaces where new ways of working are facilitated, and a day-care centre. By mixing such different functions and providing services that enhance the user experience, the authors hope to encourage the meeting of people in the lively heart of the block. Implementation For the implementation of the plan for the Soap Factory, the authors propose three different phases which could be staggered in time and altered in scope according to economic shifts, financial feasibility, population growth rates and evolving needs. Such phases are depicted in the images below in which different colours denote various the phases of potential development.

Phase 1: encouraging place-making

Phase 2: increasing access (when light rail arrives)

Phase 3: maintaining vibrancy

Conclusion As seasons change, as new and old neighbors meet, as transportation modes and routes evolve, as new tastes develop, the urban block also needs to evolve in order to cater to changes in the social, economic and cultural context. While the authors have presented a vision for a well-connected city and an urban node that is user-friendly and user-driven, the authors acknowledge that any conceptual plan may need to be altered given changing circumstances, development pressures, as well as changing preferences for housing, transportation modes and public amenities. As such, the authors stress the need to create a space that is ultimately adaptable to people’s ways of life and needs, even if that entails having to alter or cut out phases of implementation. Indeed, public space is ultimately for people.

References (for design proposal) : Keskikastari, P. (2013). IFHP/YTK Summer School: 21st Century Urban Block [PowerPoint Slides]. Retrieved directly from author. Aalto University and IFHP. YTK/IFHP Summer School Themes and Workshops. Retrieved on August 23, 2013, from http://ytksummerschool.aalto.fi/theme.html. Vasanan, A. (2012). Functional Polycentricity: Examining Metropolitan Spatial Structure through the Connectivity of Urban Sub-Centres. Urban Studio

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|