Yuqi Shao and Rongzhi Hu - EssaySmall, High-Quality, and Church-Centered Housing Development in ChicagoA low-income housing project is a precious gem that should intersperse in the neighborhood, rather than a stroke of white paint that hides the cracks of the society. For this project, we hope to serve the residents in the Douglas community area in Chicago. According to the demographic statistics by CMAP in 2020, Douglas has a population of 20,291, consisting of 11% White, 3.4% Hispanic, 66.5% Black, 14.9% Asian, and 3.8% other ethnicities. It is diverse with Black people as the dominant ethnic group. Per Chicago Data Portal, 29.6% of Douglas households are below the poverty line, and 18.2% are jobless. In the light of that, we feel an urgency to serve this group of people that are unemployed and live in hardship. We hope to establish the project in the same community area, particularly in the Bronzeville neighborhood, to enhance their quality of life and help connect them to job opportunities locally. Currently, the problem this group of people faces is maintaining a stable job and getting access to education. In Douglas, 14.3% of the residents are without a high school diploma. This lack of educational opportunities presents yet another obstacle that impedes them from becoming employed. We hope to solve these two problems through this project by selecting professional associates and strategic sites.

The majority of the members of the project team we assembled are from Chicago. We believe Chicago-based firms have the best understanding of Chicago communities. We gathered four members: Landon Bone Baker Architects, J Griffin Design LLC, Chicago Housing Authority, and Fifth Third Bank.

Landon Bone Baker Architects is an architectural firm that focuses on community development through designing housing for the overlooked in Chicago. The firm has designed affordable housing in various sizes across Chicago and built close relationships with residents. In our project, this firm can be the design principle and specialist to create passive housing, and make sure the project provides thermal comfort to dwellers.

J Griffin Design is the second team member led by Jennifer Griffin. She is a practicing design professional who works in the US, UK, and Central America on various projects including neighborhood master plans. In our project, she can design the master plan of the housing and help integrate the massing of the project neatly into its surrounding urban context.

The Chicago Housing Authority is the third member that is an experienced not-for-profit corporation created in 1937 under President Franklin Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration. Since its founding, CHA has transformed numerous Chicago neighborhoods, resolving criminal issues by providing homes for more than 63,000 households. In 2018, roughly 63% of CHA residents had a job and earned an average of $22,000 yearly. In our project, The CHA can be in charge of the residents’ selection and project management.

The last member is Fifth Third Bank. It is one of the largest consumer banks in the Midwest founded in 1858. In 1948, Fifth Third Bank established the first charitable foundation in the United States. Today the bank continues to invest money and resources in the community. In our project, this bank can be in charge of budgeting, financial planning, and advertise the project. On October 12th, 2021, the Fifth Third Bank announced its intention to invest $20 million in Chicago including Bronzeville Neighborhood, starting with improving the community and building affordable housing. Therefore, Fifth Third Bank would be the most fitting candidate to finance the project, and would be the financial provider of the project.

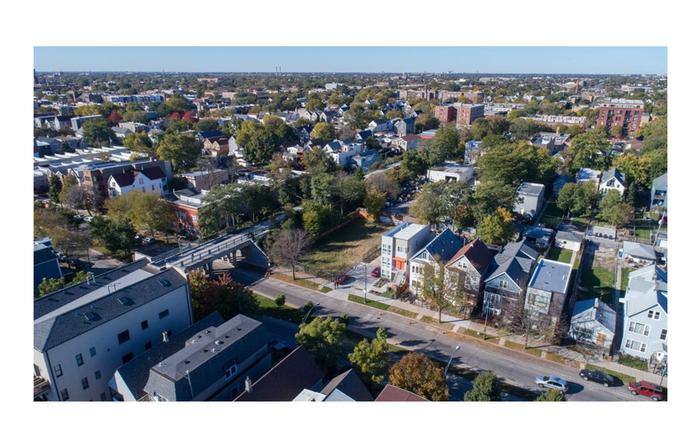

Just like seeds need nutritious soil to grow well, the housing project should be placed within constructive communities. We selected seven sites of different lot areas in the Bronzeville neighborhood, a historical district in Chicago famous for its African-American businesses in the early 20th century. The seven sites we selected are: 4649 and 4737 S State St, 4630 S Indiana Ave, 4553 S Prairie Ave, 4600 and 4643 S Calumet Ave, and 4700 S Wabash Ave, Chicago, IL. These sites are all within a five-minute walk from the 47th CTA Green Line Station and multiple bus stations. Between the sites, there’s a commercial street intersecting S State St and S Wabash Ave with grocery stores, restaurants, retailers, theaters and banks. The clusters of communal functions around the sites are convenient for the families with children, the elderly, and the disabled. This environment can enrich the life quality of the users and connect them with the neighborhood.

Moreover, there are more than twelve churches within a half-mile of the sites. These churches reflect a high moral standard of this community. At the same time, they help reduce crime rate. Architect Jennifer Griffin researched how Christian churches brought impacts to the neighborhoods in Tulsa, Oklahoma. She discovered that these churches in Tulsa can provide public gathering spaces, promote a culture of sharing (often through food), invest in neighborhood revitalization, and acquire real estate for community use. It positively impacts Tulsa’s communities by engaging in projects focused on the built environment. Furthermore, many churches are both willing and able to run after school programs that help children with homework and protect them from violence and substance abuse. It also helps kids build constructive friendships among themselves. In this way, the parents can have more time to earn money for their families. Residents who are not religious are also welcome to church food potluck and related activities. By working alongside with community centers, churches will add much to such community resources as job information exchanges, counseling services, adult education for jobs sake, and community reach-out programs. In this way, churches can participate in the existing structure of these various voluntarily provided services and support mechanisms that take care of residents’ economic and psychological needs. In conclusion, because of the highly walkable urban context, accessible transit system, a rich Black history, diversity of businesses, and the presence of community centers, we believe these sites are the most appropriate for low-income housing and its users.

In order for the project to truly reflect the lives and aspirations of the residents, we have designed it in such ways that will encourage residents to participate in the decision-making processes. It is not easy to develop an architectural program where residents truly feel that they are able to participate. In her examination of the Demonstration Disposition program in Boston (1994~2001), scholar Carolyn C. Leung shows how many residents displayed an attitude of “skepticism and suspicion” when offered a chance to participate in the decision-making processes of the program. Therefore, we will take a step-by-step approach in incorporating our residents, which will help dissolve such mental barriers between them and the project team.

For starters, we have a list of ten questions that address three aspects of the project: shared spaces within a unit, private spaces within a unit, and public spaces for the community as a whole. Below is the list:

1. What areas of your home do you use as shared spaces? What do you usually do in these spaces?

2. Do you prefer apartments, town houses, or houses? Why?

3. Please describe your ideal room and its features, including lighting, temperature, size, and furniture layout.

4. In what ways is privacy important to you? How can our design help you reach your ideal level of privacy?

5. Could you briefly describe your ideal facade style for the building?

6. Can you describe the ages and characteristics of those who will live in this apartment? What are certain needs and habits that require special accommodations in terms of the design of the space?

7. How can resources like libraries, multipurpose rooms and study areas help you? How do you plan to use them?

8. What do you do for exercise, and what are some must-haves for you in the community gym?

9. Do you need to commute regularly to work? If so, how do you commute (car, bus, train, bike, etc)?

10. Would you prefer having washers and dryers in your home or use public washers and dryers?

While starting with a list of questions can be helpful, we also recognize the limits inherent in questionnaires, especially the possibility of making users feel like objects of research instead of collaborators in a very hands-on project. As a remedy, we hope to conduct in-depth sit-down interviews with as many members of our user community as possible. Not only does the conversational format of interviews help our users feel more relaxed, but it also provides an opportunity for the project team to gather questions that the users might have for us. After these interviews, the project team will discuss and come up with a design and building plan that can realize as many of these users’ proposals as possible. Only after this is completed will we officially commence the project.

For our next step, we propose to further the participation of the user community in the design process by scheduling periodic meetings with them as a group. In order to achieve this (since it is unrealistic to meet with everyone all the time), we hope to encourage the residents to set up a committee, preferably with a chairperson, which will present the resident community as a whole. This matters because by working alongside the project team, this committee will help foster a sense of agency among residents, who will thus feel that their participation is wanted and indeed necessary.

Regarding the organization of the meetings between the project team and the resident committee, we propose a more egalitarian approach. For instance, instead of having a panel of project team members on a stage and the residents off the stage, we hope to arrange for everyone to sit in a circle. This visible gesture of inclusivity is meant to, again, deepen the conviction among residents that their presence and opinions are tantamount to the success of the project. The details can be worked out later, but the bottom line is carrying out all communications with a collaborative and transparent spirit. Since many churches located in Bronzeville show a deep commitment to serving its surrounding neighborhood, we propose using their spaces as venues for these meetings.

Considering both the resources and limitations at hand, we argue that apartments with passive design and comfortable public spaces such as gymnasiums will best serve our residents for several reasons. First, passive design apartments are energy-efficient and thus will help reduce resident spending on such things as heating and electricity. A research conducted in Elazig, Turkey in 2004 has demonstrated how passive heating features and better insulation can reduce as much as 36% of energy use in a cold area. This is great news for Chicagoans, who frequently have to endure extremely cold weather in the winter. Second, public spaces, especially those with sports facilities such as treadmills can serve both as a means for residents to improve their health and a place for interaction with one another in their community. In a study done in Seoul, South Korea in 2011, researcher Jaehyuk Lee found that for residents of high-rise apartments, the presence of such useful public spaces is directly correlated with their quality of life.

We envision the project should be rentable with a small electricity bill, just like the project The Tierra Linda Buildings in photo 4. The buildings are high-performance, energy efficient, and decrease energy costs for dwellers. It is a scattered-site housing project located near the Bloomingdale Trail that provides safe homes for 175 families and individuals over 12 different sites. All the apartments are within walking distance to schools, parks, and public services. One of the six-flat buildings is the first affordable passive housing for multi-family in Chicago. This building increases heating and cooling efficiency due to the well-insulated and tight envelope and thus decreases energy costs for renters. At the same time, it is within a quantifiable comfort level that promotes healthy living. The project should also have a central public space, just like the Mehr Als Wonhen in photo 3, a housing project masterplaned like a city that connects to the neighborhood. For our project, we will also have a common outdoor space like this that is both dynamic and recreational for the community. We also envision the project should also be welcoming and connected with nature, just like Onizuka Crossing Family Housing in photo 1, The use of wooden facade in their interior public spaces provide the residents of OCFH with a sense of warmth and makes them feel relaxed, and the units are also linked by green courtyards. We also envision the unit should be customized and easy to maintain, like Williams Terrace Senior Housing in photo 2, small, well-designed, cozy living conditions for seniors, and with a rooftop terrace.

We have opted for small apartments for several reasons. First, passive design features work best for smaller spaces. Since we are hoping to serve a low-income community, we intend for our buildings to have passive heating and cooling features, which can help significantly reduce energy consumption and thereby money spent on energy. Second, apartments within a multi-story buildings are easier to be kept safe compared to single-houses that are much more spread out. Third, smaller spaces provide residents with a better sense of privacy. Fourth, since building smaller spaces is more cost efficient, our design can free up financial resources which can be used for other purposes. Fifth, smaller spaces require less effort and time to take care of, a feature especially beneficial to single young people, disabled and the elderly. Sixth, since inhabitants of smaller homes naturally share more public spaces, they will be able to interact with one another more. This increased interaction goes hand-in-hand with our other community-building strategies. In short, small spaces can ensure and enhance the quality of our project, which will help us better serve our users.

In conclusion, we believe that small, high-quality, and church-centered housing development is the right approach to help low-income residents feel both at home yet able to integrate into their surrounding community, and beneficial to their careers and educational development. We also have outlined the different ways in which religious institutions like churches can contribute to reaching these goals, and propose a step-by-step plan to incorporate residents into the design process. For our residents, the implications of this project are two-fold. On one hand, they will move into homes with quality design features and useful shared spaces, with a host of resources aimed at securing their physical and mental well-being. Second, even after this particular project is finished, the problem-solving skills they pick up through participation in the project can be further employed to solve more issues to come in the future. Acquiring collaborative problem-solving skills can allow low-income residents to stay longer in their job positions, opening more opportunities in their career. Therefore, it will not only help them increase their income, but also allow them to stay in their new homes in the long-run. Our goal is hope to assist Bronzeville in becoming a community that does things together. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |