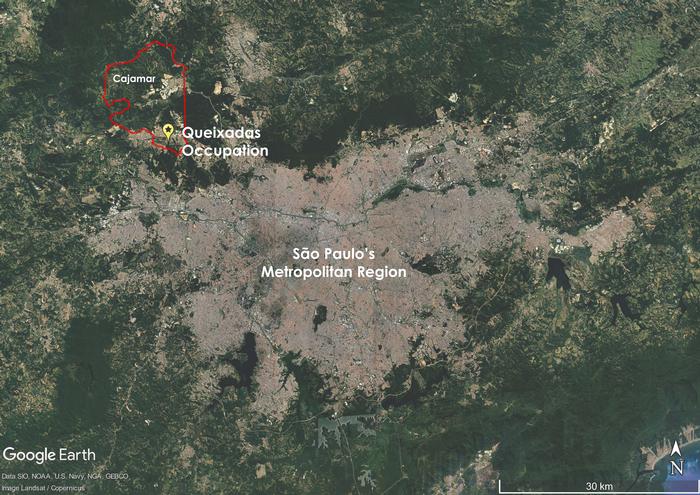

Beatriz Da Costa Gotoda - EssayFrom occupation to community: a participatory project at the edge of the metropolisOn the northernmost margins of São Paulo’s Metropolitan Region, in the city of Cajamar, lies the Queixadas occupation.

I arrive at the territory at around 9am on a Thursday and am greeted at the gate by Jesus, a Queixadas resident whom I got in contact with through Luta Popular (popular struggle, in portuguese) – an NGO that works closely with occupations throughout the country. He tells me they had to build the gate in order to contain local authorities, who used to show up unannounced and unceremoniously walk right into the territory.

We then go to an area near the entrance called “Pracinha” (little square), where I meet Bruna and Vanessa. Bruna is sitting behind a counter, from where she sells treats and snacks to fellow Queixadas. Vanessa is standing near her as she greets me (I notice she is wearing a Luta Popular t-shirt and later learn both Vanessa and Jesus are Luta Popular activists and Queixadas residents since the occupation’s inception). Vanessa, Jesus and I sit down at a table made of reused wooden boards and start our conversation.

They tell me of the historical and present contexts that are the backdrop to the community’s spirit and strive, essential to understanding the dynamics of the occupation.

The Queixadas occupation was established in mid-2019* and its name is a direct reference to a historic group of workers from the Portland Brazilian Cement Company (located in the vicinity of the city of Cajamar), who organized one of the longest syndical strikes in Latin American history (1962-69). Due to their grounded persistence, the workers named themselves after the animal “queixada” (bush pig), known to gather in packs when threatened and to emit a horrifying sound by the intense banging of their jaws (from which derives the name “queixada” – jawbone, in portuguese).

This is their third attempt at ensuring housing for the occupation’s 105 disadvantaged families. Most of the residents are from the city itself and many of them are direct descendants of the Portland factory workers – Vanessa is the granddaughter of one of the original Queixadas, she tells me. Despite this third time having been vastly more successful than the other two, the occupation has faced continuous threats to its future on that land and, consequently, to its access to housing. The latest one was an eviction order determined by local courts on October 7th, 2021, which demanded the community vacate the land by December 7th of that same year.

Fortunately, though, on the date set for eviction, the Brazilian supreme court determined the postponement of all eviction orders in the state of São Paulo to March 31st, 2022.

The project site and the land ownership dispute

At this point, we approach the topic of ownership of the land, a central part of the community’s plight for housing.

According to research carried out by Luta Popular, before the Queixadas community occupied it, the land had had no social role for about two decades. Google Earth images show the land was completely empty since at least 2002 (date of the earliest satellite image available) – for reference, 23°25'12.42"S 46°50'45.17"W. Neighbouring residents confirm this, saying the land was virtually vacant for as long as they can remember, noting that its main use had been as grounds for illicit drug use, sexual abuse and other illegal activities.

However, soon after the Queixadas community occupied the territory, a lady came to the authorities claiming to be the owner and demanding they forcefully remove the families. She claims her father obtained the land back in the 1960s over a verbal agreement with local authorities – to which Jesus referred as the kind of business done “at the twist of a mustache” (the kind involving people of power with no accountability for legal proceedings, something extremely common in land trades in Brazil, from colonial to recent times).

Adding to this contentious situation, the local government has had absolutely no public housing policies in recent years. Worse still, Jesus tells me it has scaled back previous projects and had even altered the status of the land the occupation is in. It used to fall under the “Zona Especial de Interesse Social” (special zone of social interest) category, which meant it could be used to execute public housing projects. But after the Queixadas community had occupied the territory, in their dispute to obtain ownership, the municipality stripped the precise area of the occupation from that category.

Moreover, Jesus points out that the community had itself been responsible for fulfilling their infrastructure needs, though they had had to do so irregularly. They worked alongside Luta Popular and similar NGOs, with each Queixada contributing as they could, with resources and/or know-how from construction work experience, to bring electricity, internet and clean water to the Queixadas families.

With all this in mind, Vanessa and Jesus explain that in terms of the judicial, political, and urbanistic implications of providing housing to the Queixadas families, the most straightforward solution would be for the municipality to simply grant the families ownership, as they had already done the “harder job” of integrating the territory into urban infrastructure and of beginning to establish residences on the land, even if precariously still. So, at this point, I understood that my original idea, presented in the proposal, was simply too impractical given the political circumstances in the region and that the best site for any housing project would be the Queixadas territory itself, granted they gained tenure over it.

Furthermore, according to Vanessa, local authorities have argued that the occupation does not display permanent housing conditions, which disqualifies any grant of ownership to the community. This is because the occupation’s constructions are mainly all shacks, made up of repurposed wooden boards and built directly on the earth soil of the lot. The authorities argue this means the occupation is not legitimately established and, thus, can and should be dismantled.

In this sense, Jesus and Vanessa say the Queixadas community would like to transform the shacks into permanent constructions, hoping to defeat this argument in court. The main obstacle in their way is a determination to fine any construction done in the occupied territory at R$1000 (~US$180) per day of construction work, which was issued alongside the eviction order back in October and is still in effect.

Project financing

Vanessa tells me that, without having to allocate the majority of their salaries to cover rent costs, the working members of the community have paid out of their own pockets for most of the resources needed to establish the occupation. They have been creative in finding the cheapest and most readily available materials: they partnered with a local marble yard, whose wooden boards (byproducts of marble transportation and usually disposed of in the industry) cost R$200 (~US$40) a truck-full. In addition, NGOs do help the community with crowdfunding initiatives, which were particularly helpful during the pandemic, when many Queixadas lost their jobs.

If granted ownership, the occupation residents would like to continue to finance construction costs through their own income and crowdfunding, Jesus tells me, as they really do not expect any help from the government and feel more comfortable being in control of their own expenditures. I ask them if they have tried contacting public banks to help with financing, and Vanessa tells me all their attempts were halted at the intersection of the bank’s ability to help and the lack of acknowledgement of the community’s plight by the municipal government, necessary for any public financing to take place.

Thus, in terms of the most appropriate source of funding for the project, it would be best to take advantage of the large reach of NGOs, such as Luta Popular, in gathering funds for disadvantaged families in need of housing and for the community itself to continue collaborating to unify their resources, in order to preserve their autonomy in whatever project is to be undertaken.

The Queixadas self-organization and the project team

The Queixadas community has been a self-organized group from the very beginning. According to Vanessa, the social work done by Luta Popular focuses on helping the community get politically organized against the oppressive forces they face, as per the NGO’s logo: “Organizar os de baixo para derrubar os de cima” (organize the ones at the bottom to topple the ones on top).

Bruna, from behind the counter, tells me the residents rotatively elect representatives to make up a coordination committee, of which she is a current member. The committee is responsible for organizing the weekly assemblies and for representing the Queixadas community’s interests with external parties. In these community-wide gatherings, they discuss and vote on new projects and address particular problems taking place at the occupation, such as lack of resources and disputes that may occur between residents. At the assemblies, they only reach decisions upon majority consensus.

Considering this, any participatory project to be undertaken with the community would have to thoroughly respect its social dynamics. Thus, the team assembled would involve: architect-urban planners and engineers, to provide technical knowledge and support to the community; the coordination committee, as it is the group of residents elected to represent the community’s interest with external parties; activists from Luta Popular who are closely aware of the community’s history of struggle for housing rights, such as Vanessa and Jesus, for they could provide knowledge regarding the most contentious issues they face; lawyers with experience in land issues, who would be able to aid in preventing the application of fines on construction work and, above all, help the community obtain ownership of the occupied land; and finally, for invaluable hands-on experience working with the most vulnerable in our society, undergraduate built environment students from any local university.

A participatory housing project for a marginalized community

As for the way the project would be conducted, their situation of extreme vulnerability highlights the government’s lack of effort in addressing the housing deficit so present in the metropolis and, as such, generates an opportunity for civic collaboration. This would stem from a horizontal approach by the built environment professionals involved in the project, breaking with the normal work dynamics in our field, where they are usually perceived as having more authority than those they are designing for. These professionals would be responsible for providing technical assistance, as they have access to the kinds of knowledge usually inaccessible to the popular masses. These could include, for instance, sustainable building techniques and materials, which would fit into the community’s tight budget and could further emancipate the Queixadas’ families from dependence on external resources in their strive for housing.

Moreover, they would also be responsible for ensuring the active participation of the community in the entire project, through direct collaboration in proposing solutions to the constructive and spatial issues raised. This would involve taking the questions below as a starting point, which aim to address the main constructive issues highlighted in this essay, taking as premise that the families are granted permission to remain in the territory come March 31st.

In terms of construction, what kinds of architectural interventions does the community think are essential to the continuation and enhancement of the Queixadas community?

What sort of construction techniques are they familiar with?

What sort of materials and equipment would they prefer to work with?

How did the community organize the arrangement and the construction of the residences and communal spaces?

What are the current communal spaces present in the occupation?

Are there plans to create new structures and/or communal spaces?

In terms of the urban arrangement of the territory, is there anything in need of improvement, be that materially or spatially?

Do they have plain access to public transport, health services, education and leisure from the occupied territory?

Do they have access to work opportunities from/in the occupation?

Besides the constant threats of eviction, what other threats have they faced and how have they been dealing with them?

The team would present the questions to the Queixadas coordination committee, so that they could pose them to all residents during the weekly assembly, in order to initiate debate. Then, each resident would be given a chance to answer them, be that verbally during the assembly or in writing. Next, members of the project team would gather all the answers and organize them into adequate categories (such as construction improvements, urbanistic deficits, preferred materials/techniques, etc.), from which they would be able to formulate proposals and solutions.

These would follow similar steps before actual implementation: presentation of ideas and proposals to the whole community in assembly, a moment to hear back from the residents and address their suggestions and concerns, then the elaboration of a new proposal with the necessary adjustments, eventually reaching a point where the solutions proposed could be voted in assembly and, finally, if approved, be put to practice in the territory.

As for the execution of the approved project proposal, it would be essential that the residents themselves be a part of the entire design and construction process. With many of them having construction work experience and most being willing to get their hands dirty to enhance their living conditions, as they have done before, this would be a rich opportunity for collaboration between built environment professionals and undergraduate students and the Queixadas residents, who know better than anyone their exact needs in terms of construction and living conditions. This collaboration would be, above all, necessary so that each residence is attended in accordance with the likes and needs of its residents, and so that the final product of this project corresponds to the lives and aspirations of the whole Queixadas community.

A hopeful future of continued resistance

At around noon, Jesus, Vanessa and I, after a quick tour of the territory, circle back to the entrance of the occupation. At the gate, I thank them for the opportunity to get to know their struggles and hope to continue in contact as the land ownership dispute evolves. They show deep appreciation for my choosing their community for this project, though they are aware it is entirely conceptual at this point, and we all share wishes for better days to come.

As I leave the territory, conflicting feelings emerge inside me. I feel overwhelmed at the oppressive vulnerability to which the Queixadas community is exposed on a daily basis. I feel overwhelmed at the lack of interest by those in power to attend to their basic needs, a responsibility which is incumbent upon them by our federal constitution. I feel overwhelmed at the gigantic challenge that is granting ownership of the territory to the Queixadas families, without which very little can be done to actually help them achieve adequate, permanent housing.

But, at the same time, I feel hopeful. I feel a sort of hope I had never known.

What I got to learn about this community became proof in my heart that resistance in face of profound adversity is always possible when people come together in striving for a common cause. Their persistence for almost three years, despite continuous threats and precarious living conditions, are proof that collaboration, solidarity and political involvement are powerful ingredients for survival in the vastly unequal metropolitan landscape.

With this certainty, I hope to have at least helped bring light to this community’s plight for housing, so that they can be further empowered into a hopeful future of continued resistance.

*I misinformed the year of the occupation’s inception in my proposal. It came to be in 2019, not in 2018.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |