Ayesha De Sousa and Andrew De Sousa - EssayBackwater RisingThe water is rising.

Set along the backwaters of the river Mandovi, a tangle of homes awaits the tide. Be it through tropical storms or the course of global warming, the settlement is ill-prepared to endure nature’s wrath. This is Ribandar.

A Jewel Along the Mandovi

To the outside world, Ribandar is a picturesque town, six kilometers from Goa’s capital city of Panaji. The name of the town is derived from ‘Rai Bandar’, or ‘Dock of the Royalties’. This dock served as a hub of mercantile trade during the Portuguese occupation, which enticed colonial aristocrats, viceroys and archbishops to make their abode along its lush slopes. Not long after, the impressive development of Ribandar was capped by the laying of the magnificent Ponte de Linhares, the longest bridge in the world at the time of its completion. This, however, is not the Ribandar with which we concern ourselves.

Today, the portion of the town flanked by the river is exalted by the masses and thronged by tourists. In sharp contrast, the backwater settlement of Ribandar tends to be excluded from the popular narrative - perhaps, for its mundanity. The backwater has developed organically, subject to neither the scrutiny of authority nor the wonder of visitors.

Between Two Roads

South of the Ponte lies the domain of those who subsisted on the earth and the river. The edge describing land from water was flush with mangroves that served not only as a haven for local wildlife, but also as beacons of protection. By acting as natural buffers, they protected the shoreline and its inhabitants from gusty winds and unrestrained tides. The people punctured through this thicket to create a sluice gate, which enabled them to regulate and use the backwater for irrigation, as well as to channel storm water from the land into the river. Here, the locals practiced prawn farming and cured wood. They built shrines along the water and immersed idols by the gate, out of reverence to the deities to which they owed their livelihoods.

As the settlement expanded, there also grew parallel to the edge of the water, a road, marked by the frequent passage of feet and the trundling of bullock carts. To its east, the land rose sharply to a plateau, and to its west, the land dropped gently, yielding to the backwater.

Geographically, Ribandar’s backwater settlement finds itself wedged between two roads- the Ponte de Linhares to the north and the new National Highway to the south. While the former bears witness to its past, the latter heralds the automobile, which dictates its present and future.

The village road and the settlement around it stand in shaky equilibrium between past and present. Today, bitumen has covered its mud, and motor vehicles have ousted the bullock carts. The narrow stretch is now uncomfortable and inhospitable to pedestrians. The annual tarring of the road has led to a rise in its level, to the extent that the older houses at its edge receive stormwater into their homes as an unwelcome guest.

A Not So Pretty Picture

The visual along the road belies the importance of the backwater - the two are connected only by narrow, meandering alleys, superimposed upon open gutters. These alleys, popularly known as payvats (pay:foot vat:path), are the singular means of access for the lowest income zones of the settlement. High and narrow steps ascend from the payvats, leading to densely clustered, dimly lit and poorly ventilated dwellings that are buried alongside. Almost all of these have grown vertically - organically, from the families and the spaces upon which they stand.

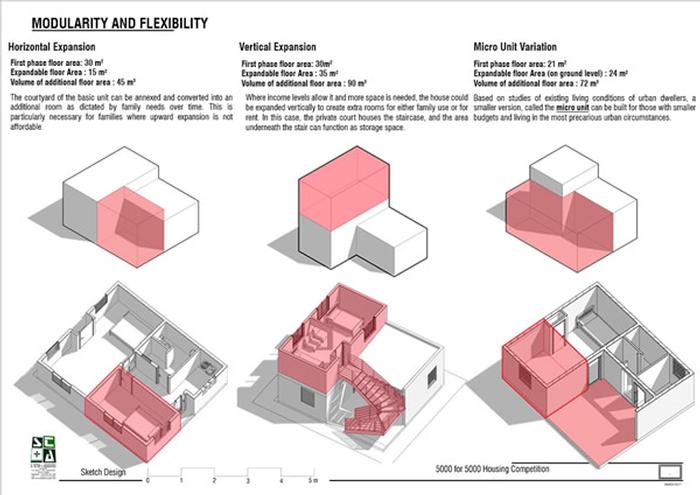

Such organic incrementality is typical of the familial structure of many residents. Ribandar is home to a close-knit community that favors multigenerational living - the colloquial ‘joint family.’ This non- nuclear character manifests itself in individual homes as well. Rather than designed, over-defined rooms, the home emerges around the needs of a growing family within a constrained space. Dwelling in Ribandar is a celebration of architecture as a vessel for living in all its dynamism. Once the vessel can no longer contain the needs of its users, it spills over - in most cases, vertically. These haphazard additions choke the existing dwellings, resulting in a claustrophobic and unsanitary urban fabric with little public space, the disadvantages of which have been laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A Bridge Too Far

Ribandar’s backwater is a mosaic of traditional systems of dwelling upon which urbanity has foisted itself. The pressures of urbanization exerted by the city, that of transportation by the new highway, along with the settlement’s organic evolution, have contributed to slapdash infrastructural development. Many homes discard their sewage directly into the backwater, with no regard for the mangroves or the wildlife that calls it home.

Turning their backs on fishing-based livelihoods, many families have transitioned to service-oriented jobs across the Ponte, in Panaji. This overdependence on the city, having resulted in a culture of consumerism and consumption, has denied the settlement its chance at economic growth.

Today, the settlement of Ribandar faces the very real threat of being drowned by the backwater which once nourished its residents and commanded their devotion. The backwater has morphed into a private dumping ground for those living along its edge. The mangroves, which have long stood guard against the vagaries of nature, are rapidly vanishing from their rightful habitat along the banks of the river. With torrential rainfall lashing the coast in the monsoons and unseasonal showers making appearances in the winter, the people fear for their homes and livelihoods. Besides this, they are fraught with worry at environmental concerns such as the lack of public sanitation, ineffective garbage disposal mechanisms and dust pollution. The settlement has managed to keep its head above water thus far, but not for much longer.

While the landscape paints a bleak picture, the enthusiasm of the people to participate in the formation and growth of their environment holds promise. These families are capable of mobilizing limited resources to catalyze the development of their neighborhood. However, their lack of expertise in planning and infrastructure, coupled with a limited knowledge about how to tackle global issues such as climate change, has threatened the community in the wake of frequent flooding. In a bid to cater to growing individual needs, the community has built itself out of its greatest asset - the backwater.

Built to Grow

The project aims at an in situ redevelopment that celebrates the intrinsic oneness between the inhabitants and the water. Its three goals are: planned, accessible housing, ecosystem regeneration, and economic diversification.

The housing will account for various family structures - joint and nuclear alike - to create systems of dwelling which echo the lived realities of the occupants. The project will, therefore, enable many families to start afresh, while keeping their heritage, beliefs and the stories behind them intact. Challenges surrounding inaccessibility, poor public sanitation and cramped lanes, largely stem from the clustered and disorderly nature of the dwellings. These can be alleviated through redevelopment that integrates an organized framework for familial and economic growth with provisions to keep the water at bay.

At the heart of the project lies the urgency to stabilize the ecosystem, which has been subject to utmost neglect out of imprudence and inaction. This objective could throw up dilemmas to find the fine line between utilization and exploitation, welfare and inequality. Of immediate priority is the revitalization of the mangroves, a natural line of defense against storms and tides that threaten to disrupt life every time it pours. The biodiversity of the settlement is quickly vanishing, and every effort must be made to ensure that flora and fauna flourish, even as construction begins to take shape. Once the systems are established and the project complete, the preservation of a sustainable legacy lies in the hands of the beneficiaries.

The initiative will reach fruition when progress in housing structures and environmental regeneration is complemented by an economic upswing. Incremental growth in commercial, mixed-use and residential spaces will tap into the community’s capacity to make calculated use of their space and resources, reducing their dependence upon Panaji. Attaining economic self-sufficiency is a stepping stone for Ribandar on the path towards providing civic amenities and upgrading public utilities. These interventions will go a long way towards forging a renewed identity for its residents.

The Road Ahead

The redevelopment in Ribandar primarily necessitates the expertise of architects who will lay its foundations in conjunction with the locals. Given that utility, sustainability and self-sufficiency are key to this context, the inputs of specialists including environmentalists, economists, urban planners and experts in water and waste management, become indispensable. The endeavors of these facilitators will be crucial not only to map out a tenable framework for the project, but also to give voice to the latent ideas and local knowledge of the residents. Cognizant that homes are dynamic and deeply personal, the participatory design process involves customization in consultation with users, to nurture a sense of ownership. Tangible interventions aside, the facilitators must guide the community towards a culture of social responsibility and accountability towards the environment.

Since the co-operative role of the local government is paramount to a successful redevelopment, its functioning will be guided by the municipality. The project will be best incentivized through a model of assisted financing, via existing schemes or systematic grants. Besides partial financing, the possibility of mobilizing community resources must not be overlooked; their provision of raw material and labor, coupled with local ingenuity can defray costs to a great extent.

For the poorest of the poor, the redevelopment could take the form of public-private partnership. This model backs the innovation, technology and assets of the private sector with the stability offered by the public sector. However, the immediate wellbeing of the community ought to take precedence over financial returns, which will be realized in the long run. The mutual investment of these parties will, thus, result in optimum utilization of resources, timely completion of micro-goals, and transparency across all fronts.

Ultimately, the redevelopment, realized as a product of collaboration and conversation, will ensure socio-economic mobility in a vibrant settlement, bolstered to face the tides of tomorrow.

Of People and Place

The power of people’s participation in the design process is two-fold. The locals know the ins and outs of the land better than the most seasoned architects, simply by virtue of their living there. Moreover, user engagement at the preliminary stage serves to forge an identity congruous with the surrounding. It is thus essential to pose effective questions to the public, not merely to gain insight, but also to foster trust and transparency between the people and the facilitators. These questions will establish an early understanding of the users, their setting - the home, physical and social environments - and the relationship between them. Such questions include:

While the questions will enable a design rooted in statistical realities, the key to an empathetic response lies in regarding the users as people, not merely as numbers. The facilitators must also be aware that their expertise is accompanied by people’s participation through the course of design- from conceptualization to completion, till it is claimed by the community as its own. Therefore, it is not a matter of simply gauging perspectives before the process, but also actively engaging with the community throughout. This will serve to ensure that accomplishments align with community ideals, to ascertain their visions and ideas for future steps, and to address any dissatisfactions they may harbor. Above all, the promise of participatory design is fulfilled, only when voices from every section of the community are heard.

The community by the backwater of Ribandar exhibits inextricable threads linking people to place, frayed by circumstance. The people, with neither experience nor expertise on their side, have defined their own environment to the detriment of their future. Brushed aside by them now, their actions have laid the foundation for impending disaster. A collaborative, in situ redevelopment is critical in affirming that people do have a claim to the tapestry of their landscape, no matter how hostile it may have turned. A prosperous community in Ribandar will set a fitting precedent for others to follow - to grow within a changing environment - independent, emboldened and with heads above rising waters.

References:

Buckminster Full Institute. (2015). Mahila Housing SEWA Trust. Bfi.org. https://www.bfi.org/ideaindex/projects/2015/mahila-housing-sewa-trust

Water Aid. (2007). Our water, our waste, our town. Wash Matters. https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/guidance%20manual%20civil%20society%20organisations%20urban%20water%20sanitation%20reforms.pdf

Webber, S. (2020, January 27). ASKING QUESTIONS THAT MATTER: THE POWER OF PARTICIPATORY DESIGN. Northeastern University. https://dsg.northeastern.edu/asking-questions-that-matter-the-power-of-participatory-design/

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |