ESSAY QUESTION

QUESTION:

In your city, how do individual communities demonstrate their presence through the buildings designed to serve that group’s social and cultural needs and endeavors?

discussion and requirements

Throughout history, individual communities within cities have shown their presence through their architecture. Distinct populations within the urban environment use architecture to facilitate gatherings that affirm their identity as a people and as a way to give their community an urban presence. In fact, a city's social and economic vitality is derived from what diverse communities contribute - and how these communities, comfortable among their urban neighbors, express themselves openly through buildings and architecture.

As a community, people may build a new structure or repurpose and remodel an existing structure to serve their specific population. In either case, the chosen location within the city, whether intentional or not, is clearly meant to express and symbolize the community's presence in the diverse urban fabric of the city. Your design studio most probably reflects a population of mixed parentage, a multitude of different personal histories, and various religious, political, and cultural affiliations. You are now asked to go out of your studio and into your city to investigate and document how these very same differences are reflected in the city’s architecture.

Find 3 buildings, each of which represents one of your city's unique communities.

- Provide the background information for the buildings: when built, by whom, for what purpose, and today’s specific use.

- Describe the most interesting aspects of the buildings in terms of the design and its location within the city.

- Architecturally, which of these buildings is most interesting to you as a representative of the community that occupies it. In depth, explain why.

As you are investigating and writing, remember that the context for all of these questions is what is to be learned from the above research and analysis towards a better understanding of the social art of architecture.

_______________

INTRODUCTION

1.0 ARCHITECTURE AND COMMUNITY

By Nezar AlSayyad (2016)

At the heart of all of the main attributes of community is the question of identity. Of course, the connection between the identity of a people and the form and culture of the architecture and urbanism they produce has been the subject of much research. Family, ethnicity, religion, language, and history have all been identified as community-constituting elements that are handed down in a process normally referred to as “tradition”. Tradition is based on valuing constraint. In a technological world of limitless choices, the conflict between the traditional and the modern in the construction of community become unavoidable. To cast traditional communities as good and modern ones as bad, or vice versa, would be naïve. As much research has demonstrated, the traditional/modern dialectic is very problematic. Dichotomies such as East vs. West, North vs. South, First World vs. Third World, core vs. periphery, and developed vs. underdeveloped nations may be considered artificial categories. An approach that takes into account the discursive constitution of communities would recognize that all social groups are constructed in relationship to one another, and that they are produced, represented, and perceived through the ideologies and narratives of situated discourse.

|

.jpg) |

The Mosque and funerary complex of Sultan al-Ahsraf Qansuh al-Ghuri, as portrayed in the nineteenth century by David Roberts in the Bazaar of the Silk Mercer.

|

The Mosque and funerary complex of Sultan al-Ahsraf Qansuh al-Ghuri, present day.

|

Both images from Cairo: Histories of a City (2013) by Nezar AlSayyad.

|

COMMUNITY AND IDENTITY

The relationship between architecture and community is as old as time itself. The concept of community itself is very complex. In some languages, the term does not even exist or it simply means “society” or “nation.” Accordingly, the concept embodies different meanings and scales in different cultures. Community may even be contested within the same language, as may be clear from the different definitions of the concept in the Oxford English Dictionary or the American Heritage Dictionary. A community may be defined as “a group of people who live in the same area” or “a group of people who have the same religion or race” or “a unified body of individuals with common interests.” This gives the term a certain fluidity that may change from place to place.

ON THE MEANING OF COMMUNITY

Hence, if one analyzes the issues of identity in communities and the built environments in the developing world, one must understand the processes by which these identities were violated, ignored, distorted, or stereotyped throughout history, and how they may still be reproduced in today’s context.

ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COMMUNITY AND ARCHITECTURE

Community architecture is the space that exists between the individual architecture of dwellings built by or for individuals to respond to their personal needs or taste on one hand, and national architecture that attempts to represent the nation state at large particularly through its public buildings, on the other hand. It plays a very important role in giving individuals a sense of belonging while at the same time allowing the nation to act as a single unit with a collective culture, history and mission.

Yet it must be recognized that the term community itself can also be hegemonic as it may define who is included and who is excluded from the group. The same attributes that bind communities together, like national origin, race or language, can and have at times been used by a dominant majority against a dominated minority. In such cases, spatial segregation and community tensions result.

The term “community" has been one of the most frequently used terms over the last 50 years of Architectural and Urban discourse. For decades, "the community" has served as a legitimization tool for architectural theorist from the early modern movement to the current “New Urbanism.” But one should ask: What is the proper definition of community as far as architecture is concerned? Can a “community" impact the design of its own space and the resulting urban form? What does it mean for communities today to exist in an increasingly globalizing world? What does it mean for communities in the age of Twitter and Facebook to exist virtually in cyberspace? What is the connection between the virtual communities of social media and the real communities that exist in physical space?

Nezar AlSayyad is a Professor of Architecture, City Planning, Urban Design, and Urban History. He is Faculty Director of the Center for Arab Societies and Environments Studies (CASES), and the co-founder of the International Association for the Study of Traditional Environments (IASTE), a scholarly association concerned with the study of indigenous vernacular and popular built environments around the world. For almost two decades AlSayyad also chaired the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Berkeley leading it to International standing.

Educated as an architect, planner, urban designer and historian, AlSayyad is principally an urbanist whose specialty is the study of cities, their urban spaces, their social practices and their economic realities. As a scholar, AlSayyad has authored and edited several books on colonialism, identity, Islamic architecture, tourism, tradition, urbanism, urban design, urban history, urban informality, and virtuality.

_______________

2.0 COMMUNITY STRUCTURES AMONG HOMELESS PEOPLE

By Barbara Knecht (1995)

|

A homeless camp in Portland, Oregon, USA (photo by Christopher Herring).

|

Nostalgic representations of community intrude into virtually any discussion on the topic of homelessness. Attempts to explain its existence, to fight against solutions, and to condemn its victims invariably incorporate perceptions of community. In this context, community is used to evoke sentimental images of home and neighborhood, and provokes emotional responses and prejudices. It is appropriated for many purposes. Messages tell us homelessness has resulted from the breakdown of family and “community” in America. A vague and unidentified "homeless community" is, in turn, blamed for the destruction of neighborhoods. People embrace these ideas and claim them as reason why formerly homeless people should not be housed in their “community.” On the other hand, when groups of homeless people band together to form makeshift villages – “communities” - in front of City Halls or in public parks, their structures are broken down and the occupants scattered. And yet, when housing is built for homeless people, the design is expected to foster and create a "sense of community" for a potentially disparate group of people who come to be housed there (continue reading).

Barbara Knecht, R.A. is a consultant in New York and Boston where she works on affordable housing and community development projects. She is the Director of Design at the Institute for Human Centered Design, an international nonprofit organization committed to enhancing the experiences of people of all ages and abilities through excellence in design. She is also co-director of the IHP “Cities in the 21st Century” program, a multi disciplinary, comparative, travel-study program for university undergraduates.

Ms. Knecht has worked for the City of New York and numerous not for profit agencies producing several thousand units of affordable housing. Her work in accessibility and universal design dates back thirty years and has informed all her projects with a human centered design perspective.

_______________

3.0 ASIA PACIFIC AWARDS FOR CULTURAL HERITAGE CONSERVATION

“In conserving the heritage of Asia and the Pacific, UNESCO seeks to encourage the role of the private sector and local communities in preserving their cultural heritage. The UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation were established in 2000 to recognize and encourage private efforts and public-private initiatives in successfully restoring structures of heritage value in the region.” Their 2016 nominations closed on April 30 (explore here). “In conserving the heritage of Asia and the Pacific, UNESCO seeks to encourage the role of the private sector and local communities in preserving their cultural heritage. The UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation were established in 2000 to recognize and encourage private efforts and public-private initiatives in successfully restoring structures of heritage value in the region.” Their 2016 nominations closed on April 30 (explore here).

_______________

4.0 CREATIVE CITIES NETWORK

.jpg) The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN), “was created in 2004 to promote cooperation with and among cities that have identified creativity as a strategic factor for sustainable urban development. The 116 cities which currently make up this network work together towards a common objective: placing creativity and cultural industries at the heart of their development plans at the local level and cooperating actively at the international level…Joining the network is a longstanding commitment; it must involve a participative process and a forward-looking approach. Cities must present a realistic action plan including specific projects, initiatives or policies to be executed in the next four years to implement the objectives of the Network.” The Network covers seven “creative fields,” one of which is “design” (explore here). The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN), “was created in 2004 to promote cooperation with and among cities that have identified creativity as a strategic factor for sustainable urban development. The 116 cities which currently make up this network work together towards a common objective: placing creativity and cultural industries at the heart of their development plans at the local level and cooperating actively at the international level…Joining the network is a longstanding commitment; it must involve a participative process and a forward-looking approach. Cities must present a realistic action plan including specific projects, initiatives or policies to be executed in the next four years to implement the objectives of the Network.” The Network covers seven “creative fields,” one of which is “design” (explore here).

|

|

|

THE ATENEO MERCANTIL DE VALENCIA (The Ateneo Mercantile Club of Valencia), Valencia, Spain, 1879. The Ateneo is located directly across form the City Hall and served the traditional, male, business community of Valencia through most of the 20th century. Now open by membership to the entire city, the club sponsors card clubs, art exhibits, film festivals, cultural and business symposia, and has a restaurant and bar available to the public. (Contributor: Benjamin Clavan)

DIKSHA BHUMI - THE BABASHAB AMBEDKAR MEMORIAL COMPLEX, Dalit Buddhist Community of Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. (Contributor: Padma Maitland)

BIBIA-ELEGU CROSS-BORDER MARKET (proposed), community market, Elegu Town, Uganda-South Sudan Border. (Contributor: Benard Acellam)  PHONGSAVAN, Hmong Market and Food Court, Milwaukee, U.S.A. The building, a typical United States-vernacular commercial structure was formerly an auto parts store that is located in a strip of other commercial businesses. There is no formal sign except for several small placards advertisingHmong businesses. It has become a center for the large minority population of Hmong who now live in the city. See also, the Hmong American Friendship Association, Inc. building, located in another repurposed commercial structure in the city. (Contributor, Arjit Sen, suggested the Hmong community buildings.)

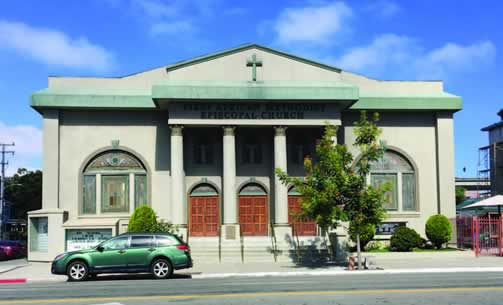

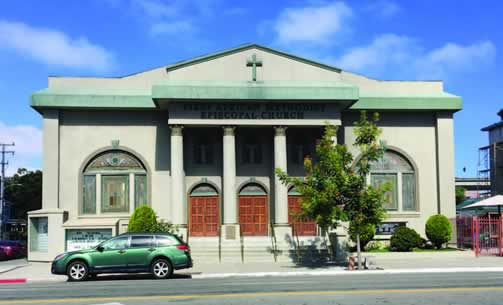

ST. MARK'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY CENTER, Milwaukee, U.S.A. (Contributor: Arijit Sen)  STRAWBERRY CREEK LODGE, Berkeley, U.S.A. A senior affordable housing community of 150 households. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  CONGREGATION BETH ISRAEL, Berkeley, U.S.A. A Modern Jewish Orthodox synagogue, this was the first synagogue in Berkeley. Established in 1924 as the Berkeley Hebrew Center, it traces its origins to the First Hebrew Congregation of Berkeley, founded in 1909. The latest structure was completed in 2005. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  YMCA of the Central Bay Area, Berkeley, U.S.A. A registered historic landmark built in 1910, expanded in 1960 and 1994. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  HAGIA SOPHIA, Istanbul, Turkey. Former Greek Orthodox basilica and Byzantine masterpiece completed in 537, converted into an imperial mosque in 1453, and declared a museum in 1935, representing a variety of communities for nearly 1500 years. (Contributor: Itamar Landau)  FRESNO BUDDHIST TEMPLE, Fresno, California, U.S.A. (Contributor: Daves Rossell)  SOCIALIST HALL, Butte, Montana, U.S.A. (Contributor: Daves Rossell)  COMMUNITY HAIR CARE CENTER, Savannah, Georgia, U.S.A. (Contributor: Daves Rossell)  JERUSALEM INTERNATIONAL YMCA, 1933, Jerusalem, Israel. Arthur Loomis Harmon, SHREVE, LAMB AND HARMON, Architect. The Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) building is celebrated as a wellspring of cultural, athletic, social and intellectual life for all who live in Israel and visitors to the country. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  CCOO (COMISIONES OBERAS DEL PAIS VALENCIANO) BUILDING, Valencia, Spain. The Country Workers’ Commission headquarters in the city, serving the community of workers throughout the region. (Contributor: Benjamin Clavan)  SESC (SERVIÇ0 SOCIAL DO COMÉRCIO) POMPEIA FACTORY PROJECT, Sao Paolo, Brazil, 1986. The SESC is a Brazilian non-profit private institution started by business owners aimed primarily for the welfare of their employees and their families. Its revenues come from a 1.5 percent payroll tax on commerce workers and thus is widely seen as representing the community of workers. This leisure center consists of a renovated factory and two new, five floor tower blocks. The complex contains tennis courts, pools, workshop areas, a library, "living rooms", exhibition halls, auditorium(s), a restaurant and a large solarium. Architect, Linda Bo Bardi. (One of two photos. Contributor: Benjamin Clavan)  SESC (SERVIÇ0 SOCIAL DO COMÉRCIO) POMPEIA FACTORY PROJECT, Sao Paolo, Brazil, 1986. The SESC is a Brazilian non-profit private institution started by business owners aimed primarily for the welfare of their employees and their families. Its revenues come from a 1.5 percent payroll tax on commerce workers and thus is widely seen as representing the community of workers. This leisure center consists of a renovated factory and two new, five floor tower blocks. The complex contains tennis courts, pools, workshop areas, a library, "living rooms", exhibition halls, auditorium(s), a restaurant and a large solarium. Architect, Linda Bo Bardi. (One of two photos. Contributor: Benjamin Clavan)  CLAREMONT TENNIS CLUB, Berkeley, USA. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  FIRST AFRICAN METHODIST CHURCH, Oakland, U.S.A., 1902. Congregation founded by free African Americans in 1816 as part of a nationwide movement in the United States. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  MOSQUE AND MINARET, Village of Teqoa, south-east of Bethlehem, Palestine. (Contributor: Shimon Dotan)  LGBT CENTER, Tel-Aviv, Israel: Formerly, the General Federation of Students and Young Workers Center completed in 1940; later re-purposed as the Dov Hoz professional school; and since 2008 Israel's first Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender public gathering place. (Contributor: Robert Ungar)  SCUOLA DI SAN NICOLO DEI GRECI, Venice, Italy. Built in 1539 as the center for a Greek fraternal organization dedicated to the spiritual, social, and economic well-being of its members. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  FRIENDSHIP CENTRE, Gaibandha, Bangladesh. Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury/URBANA architects, 2011. Built by an NGO which works with some of the poorest in the country who live mainly in riverine islands (chars) with very limited access and opportunities, Friendship uses the facility for its own training programs and also rents out spaces for meetings, training, conferences etc. to further its role as a new focus for the community. (Contributor: Nezar AlSayyad, photo at: http://www.archdaily.com/423706/friendship-centre-kashef-mahboob-chowdhury-urbana)  BERKELEY FRIENDS MEETINGHOUSE, Berkeley, USA. The Meetinghouse is a gathering place for Quakers, a Christian religious denomination that believes in service and pacifism. (Contributor: Raymond Lifchez)  SRI EKAMBARESWARAR TEMPLE at Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. Popularly known as Ekambara Nathar temple, this large complex, originally built by the Pallava dynasty (4th to 9th Century), was later reconstructed by the Chola and Vijayanagar rulers. Although the motivating force for the temple is the worship of the Hindu Lord Shiva, its use is - and probably always has been - both religious and secular, thus serving the local population in a multitude of ways. (Contributor: Paul Broches)  THE SF LGBT CENTER, San Francisco, USA. Cee/Pfau Collaborative, 2000. The LGBT Center was established in the 1970s to connect the diverse lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, and trans communities with important resources. (Contributor: Thea Chroman).

|

|

.jpg)

“In conserving the heritage of Asia and the Pacific, UNESCO seeks to encourage the role of the private sector and local communities in preserving their cultural heritage. The UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation were established in 2000 to recognize and encourage private efforts and public-private initiatives in successfully restoring structures of heritage value in the region.” Their 2016 nominations closed on April 30 (

“In conserving the heritage of Asia and the Pacific, UNESCO seeks to encourage the role of the private sector and local communities in preserving their cultural heritage. The UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation were established in 2000 to recognize and encourage private efforts and public-private initiatives in successfully restoring structures of heritage value in the region.” Their 2016 nominations closed on April 30 (.jpg) The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN), “was created in 2004 to promote cooperation with and among cities that have identified creativity as a strategic factor for sustainable urban development. The 116 cities which currently make up this network work together towards a common objective: placing creativity and cultural industries at the heart of their development plans at the local level and cooperating actively at the international level…Joining the network is a longstanding commitment; it must involve a participative process and a forward-looking approach. Cities must present a realistic action plan including specific projects, initiatives or policies to be executed in the next four years to implement the objectives of the Network.” The Network covers seven “creative fields,” one of which is “design” (

The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN), “was created in 2004 to promote cooperation with and among cities that have identified creativity as a strategic factor for sustainable urban development. The 116 cities which currently make up this network work together towards a common objective: placing creativity and cultural industries at the heart of their development plans at the local level and cooperating actively at the international level…Joining the network is a longstanding commitment; it must involve a participative process and a forward-looking approach. Cities must present a realistic action plan including specific projects, initiatives or policies to be executed in the next four years to implement the objectives of the Network.” The Network covers seven “creative fields,” one of which is “design” (