Report From Winner

SECOND REPORT FROM 2007 TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP WINNER, BUDOOR BUKHARI:

(Ed. note: Budoor Bukhari continues to explore the project and themes on which she based her 2007 Travel competition entry. Below, is correspondence and photographs describing her recent fieldwork for this endeavor. Of special interest is Ms. Bukhari’s anthropological sensitivity to working as an “outsider” with a local population. Implementing projects which reflect the social art of architecture requires much more than paper, pencil (or computer software), and a good idea. First and foremost, it requires an understanding of the human component of what we do as architects.)

March, 2008

.jpg) |

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Dear Professor Lifchez,

I returned only two days back from an exhausting yet extremely memorable and rewardingjourney to the Kadalu villages located in the southern reaches of the Dinder National Park. The project is to design an ecolodge for the National Park that complies with the principles of community-based ecotourism development. It is proposed as one of the three lodges to be located at the entrances from each of the three States that the Dinder National Park falls in, and this one is located in the Blue Nile State a couple of miles off the town of Al Roseiris - a short distance into the park's boundaries. I first wrote about this in my BERKELEY PRIZE Essay. It is an independent proposal that I'm making towards my final thesis design project.

The purpose of this trip was to make a site visit and conduct some field studies. While the trip was 5 days in all, only two were spent in the area as the rest were taken up by traveling to and from the location. Due to the fact that I went with the NGO Nile Basin Initiative, which had its own

|

agenda, we were constantly on the move and what I was capable of achieving wasn't as comprehensive as I would have hoped. Nevertheless, it was definitely worthwhile. Tourism development is surely not the right thing for the moment, given the communities' struggle for basic survival. But it is a real and pending challenge I am attempting to tackle at a somewhat hypothetical level. Yet the issue of materiality is crucial to address and the very small participatory workshop I organized and engagement with members of the communities helped me gain a better understanding that can inform my design process. Very little time left for my final review and lots of work to be done!

Below, I’ve included correspondence between my advisor in Sudan, Mr. Adil, and myself about how I should best approach this fieldwork. I hope it can help shed some light on the research process

Warm regards,

Budoor

February, 2008

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Greetings Mr. Adil,

Since I began this project I have wondered about how I will approach the communities in which I hope to work, and how my visit to their villages would make a difference, however small, without intruding or offending them. When I was in South Africa on the BERKELEY PRIZE Travel Fellowship, an Australian architect who has experience working with marginal communities highlighted that it is extremely important to make a positive change the minute you set foot into the community so that they accept your presence and also feel compelled to assist. Since I was going in to explore in more detail the local building technologies and materials in these communities in which I will be working, I had been considering carrying along two items. I asked my advisor in Sudan, Mr. Adil, his opinion as to whether it was a smart thing to do or not:

1) Portable printed paper plot(s) with simple photos to aid me in communication, containing images to do with materials and technologies.

|

2) (And this is what I am most unsure about, but have already purchased:) Two bambootorches, along with a small container of accompanying oil. I wanted to take these to demonstrate to the communities one of the many things that can be done with bamboo. In this case, without dependence on an electricity supply or generators for at least the short term, torches operated with oil and cotton like these can be efficient in providing night lighting.

Although they will be a hassle to bring over, it seems worthwhile… But I am not sure. Will it be problematic to carry such a torches with us? Will it become an issue in terms of who in the community gets to keep them? Is their understanding of development is that they will get electricity like everyone else, and might such a contribution as the torches be considered an attempt to keep them behind? Or would it instead be appreciated and become a source of delight and light up at least a part of one of the villages during night hours for a change?

Thank you for being patient with me,

Budoor

February, 2008

Dinder National Park, Sudan

Dear Budoor,

Salam kateer,

Kadalo people are very simple and courteous. They have gone through a lot of misery and sufferings during the occupation of their area by the Rebels (Abdeaziz Khalid, the SPLA). They are quite weary about outsiders, but once they trust you they fully open their souls and homes to you. I think both ideas are brilliant to break ice and to add some (light) to their lives. Of course they appreciate any development efforts as they are in close proximity to Rpsseiris and Damazine towns. In some villages there is diesel-generated electricity, and in one village the Dinder Project has supplied a small solar unit.

So, I don't think there would be any problem in bringing the bamboo lighters except for their transport to Sudan.

My very warm regards,

Adil

FIRST REPORT FROM 2007 TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP WINNER, BUDOOR BUKHARI:

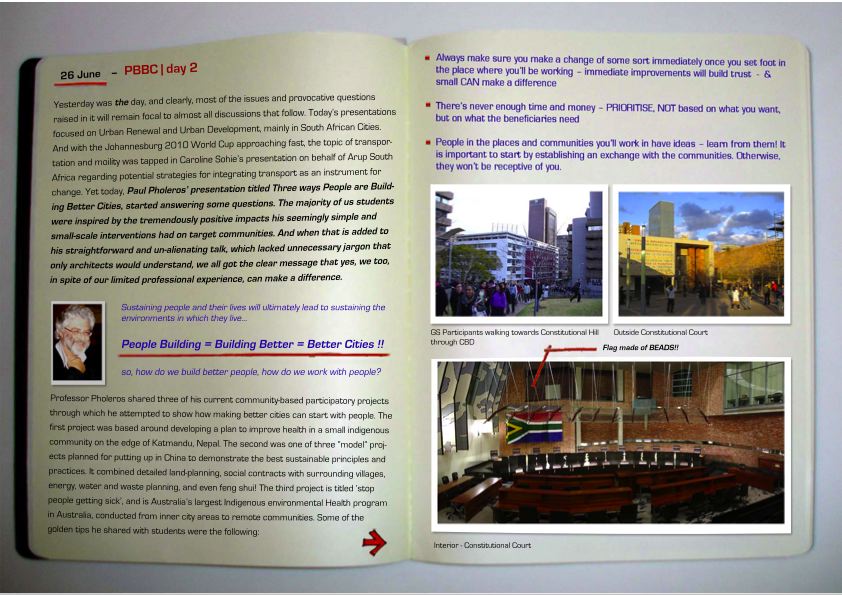

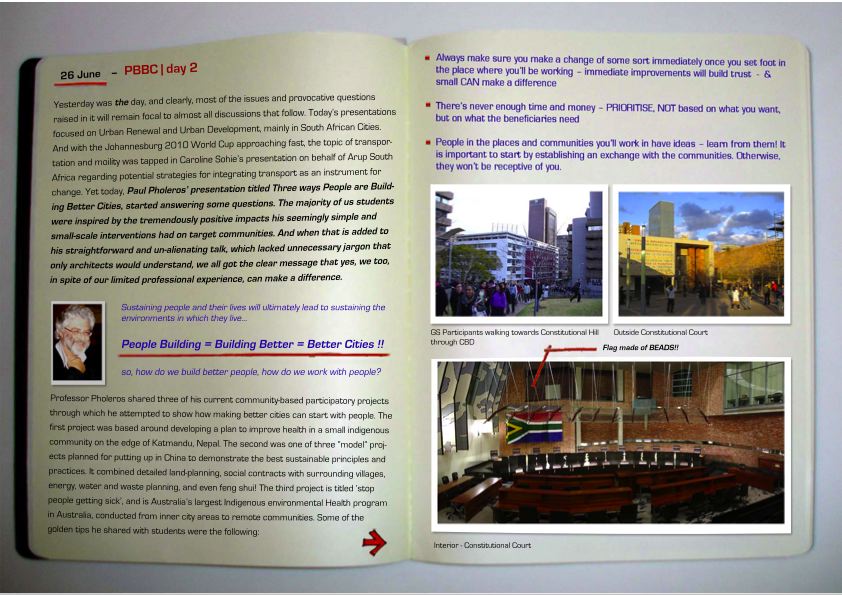

Collective Deliberation/ Global Studio Johannesburg 2007

The flight from Abu Dhabi International Airport to O R Tambo International Airport lasted 8 long hours. The endless options of entertainment programs failed in their attempt to overwhelm my enthusiasm as I continued to reflect upon the contents of the many books, tour guides and travel tips I had delved into prior to taking off to South Africa. This year’s People Building Better Cities (PBBC) Conference & Global Studio Johannesburg took us to the southern tip of the African continent to experience first hand the challenges Sub-Saharan Africa faces in its struggle towards sustainable development. Set up under the Millennium Development Goals’ task force on improving the lives of slum dwellers, Global Studio aims to promote participatory democracy and the development of critical and imaginative thinking. By building on the concept of the design professional as enabler and communities as active agents of change, Global Studio adopts an interdisciplinary, situated approach to design education. Its focus is site specific, involves participatory planning and design processes with marginalized communities, and the creation of innovative solutions towards positive change. The Johannesburg studio of June/July 2007 brought together over 100 students from 52 universities in over 20 countries, and we all built new partnerships while working collaboratively as teams and with the communities for almost a month.

In spite of the fact that this was my first experience with such extremely cold weather (even snow during my first days there) I managed to actually survive until the end. My experience has been recorded in a diary of daily activities as a participant in Global Studio, and a refined and digitized version is available for downloading. The short summary below provides a brief account of my experience, which I’m hoping will entice you to check out my full travel diary…

During our first investigative walk through Diepsloot with our amazing guide Bobo, many of the children rushed over with excitement to greet us as their families watched curiously from a distance. I immediately recalled my similar experience walking through the villages in the Dinder National Park (DNP) and thought about the shared challenges both communities have to confront. In spite of being marginalized, impoverished, and lacking access to basic services, one cannot help but admire the innovation evident in the spaces created by the communities. Whether speaking of Diepsloot or the villages in the DNP, the people of both communities demonstrate a capacity for developing localized solutions to the problems they face in spite of the lack of readily available resources. In their humble yet highly commendable attempts at self-realization and self-help, they teach us that our notion of sustainability should cease to be limited to materials and environmental control systems. Rather it should expand and be redefined to take into consideration the importance of sustaining people! Sustaining people will ultimately lead to sustaining their environments. As Professor Paul Pholeros had put it:

People Building = Building Better = Better Cities!

Indeed, this is one of the core issues discussed in PBBC as well as a major lesson learnt through participatory work with the communities. As architects, and more generally as building professionals, we need to change our perceptions, mediate and appreciate that people in the places we work in have knowledge to contribute and genuine needs that must be considered. To learn from them, it is crucial to focus on establishing an exchange with the communities to enable them to be receptive to our proposals and later take ownership of them. We have learnt that it is in establishing such a culture of engagement that the key to participatory processes lays.

Many other issues of global concern revolving around slum upgrading and urban renewal were covered during the PBBC conference. The most prominent amongst those was the discussion on the formal versus the informal in contemporary urban settings, and the immense challenges and limitations the latter poses in the face of urban planning and design. How do we deal with the informal? Is eradication, relocation or aestheticization (sic) the solution? And given that informality is born out of the transience of populations and economies, how can we accommodate into our development programs such dynamics in order to provide better opportunities of livelihood for communities?

Some of the other questions and hot topics raised related to the issue of tourism and the commodification of culture and poverty, as well as that of migration and its effects on marginalized communities. Once again, there are no easy answers, and all the questions that arose within the stimulating environment created by the gathering of many students and professionals, ultimately served to highlight the role of architecture as provocative.

The PBBC conference concluded with an introduction to the socio-economic context of the townships of Alexandra and Diepsloot that we worked within. We were provided with an overview about the communities and discussed how city policies and inhabitants have shaped the townships. The presentations were made by International Affairs students from the New School for Social Research in New York as well as students in Urban Planning from the University of Witswatersrand. In a collaborative effort that sought to bridge the gap between the social sciences and urban planning, the students had conducted extensive research in the fields of housing, participatory governance, the environment and the informal economy. Their presentations complemented those given later by representatives from the City of Johannesburg and the Director of the Alexandra Renewal project, in which the two highlighted their concerns, currently proposed interventions, as well as their expectations of Global Studio.

Five key learning points from their presentations included:

• The importance of location to the poor

• The complexity of urban/rural linkages

• The deep societal impacts of apartheid planning and the struggle against it

• The significance of acting through a responsive understanding of the socio-economic profile of the area

• The importance of density to the informal economy in townships

Through the safety and cultural sensitivities workshop, participants were reminded of the significance of going in with humility and a willingness to listen, observe and understand. We were divided into three groups: Alexandra, Diepsloot and Marshalltown (JoVi), the latter dealing with slum upgrading in the inner city of Joburg. I was a member of the Diepsloot group, the largest group that faced the largest challenges, as the township is only 12 years old, and still receiving new proposals for development.

Equipped with information and recommendations gathered during PBBC, we visited Diepsloot for the first time on July 5th. After meeting with representatives from community committees and members from local youth organizations, we took a guided tour that covered parts of formal and informal areas. Heaps of trash, narrow, unpaved roads, standing sewage water and inconvenient public toilets caught our attention. Those, coupled with other group observations relating to the settlement’s physical features and the community’s problems and practices, provided the foundation for the intensive, two-week participatory design workshop that followed. Working within our respective groups, we attempted to develop ways in which to turn our observations and ideas into innovative, sophisticated and practical design solutions for the community.

Initially, the projects were very vague and undefined as we made several visits to Diepsloot and talked to members of the community. The purpose of those visits and mapping initiatives was to observe patterns. We then collectively discussed the many challenges and problems that could potentially be tackled within particular project areas. After establishing a number of projects for each area, we sifted through the list, consolidated some of the projects and removed others in order to identify which issues we would address. The final subgroups for Diepsloot were: Housing, the Environment, Public Spaces and Information. I was in the Housing group, which proposed two projects for Diepsloot. The first was a participatory housing design workshop with members from the community that included children as well, and the second was a poster project that aimed at building local capacity through “Communicating Community Innovations”. The proposal was borne out of our observation of the community’s innovations in building and the subsequent desire to provide an appropriate medium for communicating those innovations. We gave the poster the title: “10 ways to better your shack for less than R70!”

From Suzanne’s agricultural plots and farming workshops to David’s transformation of an environmentally degraded area into a sculpture garden, to a single mother’s construction of a beautiful house amidst the shacks - complete with garage for her future car – many of the people we have met and places we have been in Diepsloot demonstrate an inherent capability to do the very best with available resources and without contributions from architects or designers. Nevertheless, what the community perhaps does need is awareness programs, education, and assistance with strengthening their community committees so that they can empower and help themselves. The projects proposed by the other 2 groups all exhibited this aspect in their final products, for the same applies to Alexandra, Marshalltown, as well as to almost all other similar settlements. Community leaders and members were active participants throughout our research, and many were present in the final Global Studio presentations on July 18th.

Participation was not merely between the communities and Global Studio, but also amongst Global Studio Participants. Working together in teams for almost a month served to bridge the gaps of difference, and enabled us to collectively appreciate our capacity. Resonating the words of Georgia Bowen from the University of Sydney from the talk she gave during PBBC, we have no professional experience as yet, but what we do have is passion and enthusiasm, and an excited will to play our role in contributing to urban development and renewal, and thus the building of better future cities. It was ultimately about Young Designers Creating Positive Change. Yet, we not only worked together, but also enjoyed walking together in large groups as we explored beloved Johannesburg in our free time. The travel tips we all looked into and heard from friends included warnings to stay away from dangerous neighborhoods such as Hillbrow, Berea and Yeoville. Ironically, our accommodation was located right at the heart of those neighborhoods, and it turned out to be nowhere close to as bad as what we were told. In fact, it was our experiences on the streets of those neighborhoods, and those of the less-privileged settlements we worked in, to which we owe what I believe to be a truly authentic experience of Joburg.

The continued struggle for freedom can be observed in every corner of South Africa. I have been intrigued by the diversity of its citizens and the many progressive policies it attempts to put through in the face of the challenges raised by its dark history. People of diverse backgrounds intermix with a stunning propensity, and one can’t help but swing along with the vibe of everyday life. My many new friends from Global Studio were some of the most wonderful I’ve met, and I already miss them and long to meet with as many of them as possible once again, sometime, somewhere.

Joining Global Studio as a Berkeley Travel Fellow certainly allowed insight into socially significant practices and provided an opportunity to learn valuable lessons from peers and professionals. This will not only inform work on my final thesis research, but has left me with a memorable experience that will surely pave the way for a future career in socially responsible architecture.

Ghandi once said: “ Truly speaking, it was after I went to South Africa that I became what I am now. My love for South Africa and my concern for her problems are no less than for India.” Twenty-eight short days don’t entitle me to make the very same statement, yet, truly speaking, my brief visit to that land of beautiful colors and stunning contrasts has nurtured in me a renewed keenness…a desire to firmly continue pursuing my vow to contribute to pushing Sudan, and thus Africa, upwards.

REPORTS FROM BERKELEY PRIZE TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP LIAISON, ANDREW AMARA, (2006 BERKELEY PRIZE TRAVEL FELLOW):

(Report 1 of 3)

People Building Better Cities / Global Studio 2007. Wits University, Johannesburg - Week 1

I was among one of the first to arrive in Johannesburg. Four other Global Studio participants were also waiting at the airport. The cold stinging wind immediately hit me the moment I stepped out of the airport. This is the coldest weather I have ever experienced – on the third day here it even snowed. (Johannesburg’s first snow in 30 years - my first snow experience).

People Building Better Cities conference and Global Studio is bringing students, academics and professionals in city building professions from developing and developed countries to take part in an interdisciplinary forum and studio in Johannesburg in 2007. Global Studio provides opportunities to develop new modes of professional education and practice with policy and research implications as well as possibilities for developing networks and partnerships. Global Studio is an on-going teaching and research project.

Participants will work collaboratively in teams with local communities in Alexandra and Diepsloot to develop propositions and strategies that can assist in improving people’s lives, while developing knowledge and skills in this area of work.

People Building Better Cities - PBBC

The PBBC conference ran from June 25th – 28th. It oriented the participants to the situation in Johannesburg, its living conditions, urban issues and problems, as well as showcasing interventions that try to improve the lives of the underprivileged, from South Africa and around the world.

The speakers came from various parts of the world and presented different approaches to working with local communities. Below is a summary of some of the presentations.

Making the Alexander Interpretation Center - Peter Rich

This building project in Alexander (Alex) drew on some of the unique characteristics of the area such as the backyard, street, and the defensible spaces in-between. Lessons were learned from local people before beginning to design - for example, the interactive edges in the settlement (with in the competing grids in Alex). The building form was developed to follow the character of Alex housing, as a stage set that allows the ‘rural’, ‘urban scavenger’ and ‘sophisticated’ to flexibly use the space. The people can add to the building temporary structures, shades etc.

Walter Sisulu Square - Pierre Swanepoel

StudioMAS won the competition for this project. They developed a concept inspired by the historical importance of the site. Materials from demolished buildings on the site were reused to make monuments; two pavilions supported by a forest of columns were built on opposite sides of the site. The local people were trained to make some of the building elements.

How Public & Civic Space operate in Townships?

This talk highlighted the question of how people develop a sense of ownership and belonging in a community. Some ideas included the design of space as a ‘skeleton’ that the people can build into/onto. Another way is to include identity features in the space.

Some of the other issues discussed included:

-

How do you design to keep track with the rapidly changing tastes, demands and conditions in Johannesburg?

-

How do you deal with numbers and density versus quality of space?

-

The freedom struggle is a big factor in the politics, economics and social life in South Africa.

-

The built environment was never destroyed, but lived on through the revolution in South Africa. The country therefore has to approach the issue of heritage differently.

-

Africans gather in spaces in between buildings

-

African art is shaped by function rather that abstract beauty.

-

Culture in Johannesburg has a huge potential as an industry, but we need to know how to manage it.

-

Buildings should tell the people’s story

One of the new lessons I have learned is to design for ‘adaptation after construction’: thinking of the building as a scaffold/skeleton which the user can add to - creating an ‘open endedness’ in buildings that suggest various ways in which space can be used. It is interesting to compare how people use community buildings versus how the architect intended it to be used. These ideas came through in the presentations by Mpethi Morojelo (MMA- architect firm) and Professor P. T. Roman.

During the week we toured the city, visited some of the townships, public spaces and buildings and historical facilities.

On the 30th June, we went on field trips in two separate groups; one to Durban and the other Maputo. I choose to visit Maputo because I had heard a lot about the Portuguese architecture there and I wanted to see how the coastal town had developed (also because it is warmer than Johannesburg).

It was interesting to see the change of landscape along the journey: flat plains to hills and mountains, to plantations of oranges and flowers, to Maputo’s streets lined with palm trees.

Day two of the trip, we listen to a lecture by Jose Forjaz, one of Mozambique’s prominent architects and director of the country’s only architecture school. Later on, students from this architecture school took us on a tour of the town. Maputo is a nice beautiful city with colonial Portuguese buildings – we visited many buildings by Pancho Guedes (a reknown Portuguese architect), Gustavo Effiel and Jose Forjaz among others. The people are friendly and the sea food is tasty. However, not much building development and maintenance is being done. The city seems to be stuck in the ‘old era’ instead of exploring new approaches, ideas and integrating new technologies to combat problems associated with urban centers today.

Today we traveled back to Johannesburg, and while we prepare to begin the studio tomorrow, everyone already has a story to tell.

‘For many years South Africa was isolated. In the post apartheid era it has become one of the more connected countries in the world, and much admired for the peaceful transition from the apartheid to post apartheid era. While social problems, poverty and inequality still exist, much progress has been made. As former president Nelson Mandela once said ... after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb.’

www.theglobalstudio.com

(Report 2 of 3)

People Building Better Cities / Global Studio 2007. Wits University, Johannesburg - Week 2

|

|

Children sketching different ideas during a community event in Alexandra organised by Global Studio. |

On July 3rd the Global Studio began session. We had a few lectures from the Johannesburg City planning department to introduce us to the city context and their expectations from global studio.

Students, mentors and project associates were then divided into 3 groups to work in 3 different areas:

1. Alexandra

2. Diepsloot

3. JoVi – Johannesburg Village.

Alexandra

Alexandra (also known as Alex) is a township near the center of Johannesburg, in the province of Gauteng, South Africa. The township is known as one of the sites for the awakening of the liberation struggle against the Apartheid system.

The township land was originally part of a farm that belonged to a farmer whose surname was Papenfus. Papenfus named the area after his wife, Alexandra, in 1904. In 1912, Alexandra was proclaimed a ‘native township’ before the Land Act of 1913 was enacted, and became one of the urban areas where black people could own land under freehold title.

By 1916, Alexandra was under the management of the Health Committee and had a population of 30,000 people.

.jpg) |

|

One of the site groups presenting preliminary findings and analysis of the Diepsloot site and community. |

The township’s infrastructure was designed for a population of about 70,000. Current population, however, varies widely and estimates range from 180,000 to 750,000 people living in some 800 hectares.

Alexandra was perceived as a threat to the surrounding white middle-class population due to the overcrowding conditions, high levels of unemployment, crime and the rapidly deteriorating basic services in the township. From 1948 and during the Apartheid years, Alexandra remained under the administration of the Department of Native Affairs whose main agenda was to: a) reduce the population size in the township, b) have control of movement into the area, and, c) expropriate the population of freehold property. At the same time, nearly 50,000 people were removed from Alexandra and sent to Thembisa and Soweto.

Alexandra has a privileged location within Johannesburg. It sits next to key roads as well as the main highway linking Johannesburg and Pretoria. It is also located close to the economic hubs of Sandton, Wynberg, and other industrial and commercial areas.

.jpg) |

|

A section of Yukskei river that divides the formal and informal housing in Alexandra |

The Alexandra Renewal Project: The multi-million-rand Alexandra Renewal Project is aimed "to decongest and address the need to create a healthy and clean living environment." In 2001, in preparation for the project, some 6,000 households were removed from the banks of the Yukskei River to Diepsloot (see below) and Brahmfischerville. The government aimed to “dedensify” Alexandra and justified these relocations by arguing that they were either “illegal”or within the flood zone (Mail and Gaurdian 29 June 2001, cited in Robins 2002).

Housing: Housing in Alex is somewhat diversified. The most recent census figures estimate the local population to be 350,000, but researchers put the figure at 250,000. Residents live in 8,500 formal houses, 34,000 shacks, 3 hostel complexes, 2,500 flats, and numerous old factories and buildings (Alexandra Renewal Project website). Many dwellings in the township have been expanded through the addition of 3-6 separate rooms built in each house’s garden. Typically these rooms each house a separate family, who rents the space from the homeowner. Many of these “backyard shacks” are built of brick or blocks. There are some 20,000 shacks, including around 7,000 in backyards (Report on the Interactive Planning Workshop for Johannesburg, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council, September 27-30, 2000).

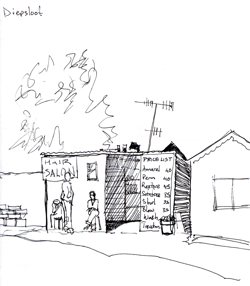

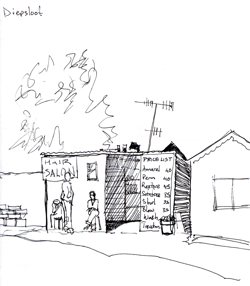

Diepsloot

Diepsloot is a sprawling township, of approximately 150,000 people located next to the Diepsloot Nature Reserve, just 15 miles northeast of Johannesburg, in Region 1. The name Diepsloot comes from the Afrikaans and it means ‘valley in the village.’ It is one of the fastest-growing townships in Gauteng.

|

Andrew Amara

A sketch of one of the shacks in Diepsloot; questioning the form, materials and the tall light pole. |

In 1995, Diepsloot West Township was established near the upscale suburbs of Chartwell and Dainfern. The area was intended to serve as a transit camp from families who had been removed from Zevenfontein to the west of Diepsloot. Although the camp was meant to be temporary, it has become a permanent home to many families. The Transvaal Provincial Administration – back then the local authority – developed 1,124 plots into formal housing stands. Development began in 1999 under the former Northern Municipality Local Government. At that time, some 4,000 families lived in backyard shacks and another 6,000 in the camp’s reception area. In 2001, as part of the Alexandra Renewal Project, the Gauteng Government relocated around 5,000 families from the banks of the Jukksei River in Alexandra to Diepsloot. The rapid expansion of Diepsloot’s population has strained the area’s scarce infrastructure and resources. The housing situation is especially dire, in part because relocated families did not quality for government housing benefits (City of Johannesburg website).

Today, Diepsloot is home to around 150,000 people, many of whom live in 3m x 2m shacks assembled from scrap wood, metal, cardboard, and plastic. Access to basic services like sewage, running water, and garbage removal are severely inadequate.

Poverty and unemployment are severe in the area: about half the population is unemployed.

|

|

Shacks (temporary tin and timber shelters) in Diepsloot. |

Housing: There are 7,139 households in the formal townships of Diepsloot West and Diepsloot West (Extensions 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 9). Informal settlements dot the area around Diepsloot, and these settlements contain most of the population: an estimated 16,000 families, most living in backyard shacks on formal stands (City of Johannesburg website).

Considering the extreme poverty, the high rates of unemployment, and the lack of basic resources in the township locals are facing a new problem with illegal immigration into Diepsloot. For instance, there is a constant influx of refugees, primarily from Somalia and the Congo, and, in the past few years, more illegal immigrants come from Zimbabwe. This, has triggered a rising tension and violence between the locals who believe that the new comers are only making the situation worse by taking their jobs away and overcrowding the township where there is hardly any space left for more people.

In July 2004, violent protests broke out in Diepsloot, triggered by rumors that families from the area would be removed to Brits, 45km away in the North West province (City of Johannesburg website).

|

Andrew Amara

A sketch of a roadside salon in Diepsloot, an example of informal commerce developing along the road. |

Government officials estimate that almost 5,000 RDP houses have been built in the area, and that more than 700 housing stands with water and sanitation have been allocated (City of Johannesburg website).

Governance and Civil Society: A satellite Multi-Purpose Community Center (MPCC) was established in Diepsloot in December 2002 through a partnership between the local government and non-governmental organisations. The NGO Bonalisedi ceded space for the MPCC, and Spoornet donated containers to serve as offices for different government departments.

JoVi

This village is in the south east corner of Johannesburg inner city. It is a rundown area with neglected old warehouses and blocks in dire need of renovation. At present there are some residents in the area however the streets are not as busy as the rest of city, and the planning council is still generating ideas for the site.

The three global studio groups are to study these areas, meet the local people, councilors and city planners as there seek innovative solutions to the problems of each site.

My role has been to help facilitate events, resources (e.g. maps), provide support and guidance to student participants and help generate ideas and final production as the studio progresses. I am in the Diepsloot group and we are at the stage of crystallizing project ideas. We have had two visits to the area, where we got to meet and talk to the locals, councilors and youth. We walk through the settlements, entered a few shacks, traversed the river that divides the housings, turned round at the ‘reception area’ and moved along the boundaries.

My first impression of Diepsloot was that it is a bustling community full of life and energy. It was simply good to talk

.jpg) |

|

Global studio participants at work in one of the architecture studios at Witwatersrand University. |

with Godfrey and some of the other locals, exchange thoughts and ideas. There is so much happening here and yet still a lot lacking. The housing is insufficient and congested, waste management is awful and hygiene is poor.

Yet there is the ever pressing question: How do you create design interventions in this place without disturbing the sense of community and sharing?

Through sketches, photography and interviews, we are collecting information and data. We are also teaming up with New School graduate students in international affairs and urban policy. The New School students, together with urban planning students from the University of the Witwatersrand, have already spent the past first three weeks conducting fieldwork in the townships of Johannesburg. Their research findings and results will feed into our projects.

Next week we visit the area again as we begin to develop the project.

References:

• City of Johannesburg website: http://www.joburg.org.za/2004/july/july27_diepsloot.stm

• http://africanlanguages.com/south_africa/place_names_sagns.html

• http://www.alexandra.co.za/01_about/contents.htm

• Gauteng Provincial Government website http://www.gpg.gov.za/services/mpcc/diepsloot.html

- Field Study Conversations with New School graduate students

July 31, 2007

Kampala, Uganda

Dear Professor Lifchez,

Hope all is well.

I am now back home in Uganda. The last two weeks have been busy. The studio produced innovative solutions, some small on-site interventions or week long refurbishments and installations to broad visions and plans for some sites. The New School students were very helpful. I learned a lot from the experiences and disciplines of the studio participants, although at times it was through heated debates.

I now have a different perspective of Johannesburg; there is more to it than crime and HIV/AIDS.

Italy was a whole new experience, made more acute by the transition from the South African Wits University to the lakeside villa in Italy. It is a very beautiful place - very inspiring how they have strictly preserved the ancient architectural styles (they are even making money out of it).

The participants in Bellagio, Italy were impressed with our projects when we presented them at the Urban Summit. One of the agendas was how to formalise such a studio or introduce the model into universities.

I also met very many great minds. Hopefully I will build on these networks.

My Vancouver experience with Global Studio also inspired me to get involved with underprivileged communities in Uganda. I have been planning a student project (based on the Global Studiomodel) which involves spending time with Internal Displaced People in war torn Northern Uganda; and engaging them in rebuilding and resettlement alternatives. I am now investigating if and how East African Universities in addition to local schools can be involved.

My report from Bellagio follows.

All the best,

Andrew

(Report 3 of 3)

Innovations for an Urban World / A Global Urban Summit.

The Rockefeller Foundation, Bellagio, Italy - July, 2007.

During the week of July 22, six of us traveled to Bellagio, Italy, to represent Global Studio at the Urban Summit. Bellagio is a beautiful old village in the north of Italy.

The Urban Summit convened leaders from the private and public sectors to explore opportunities to foster healthy and sustainable cities. Over the course of four weeks the summit addressed issues of public health, shelter, water, sanitation, planning and adaptation to climate change.

“Time is short. Today, for the first time in the world’s history, the majority of its population lives in cities. Urban development is rapid, and its impacts are long-lasting. Unless urban areas can be made more sustainable, and rural life more tolerable, the legacy of negative environmental and social costs will become irreversible…

Yet much city planning, design and policy-making remains reactive, and presumes that urban development is only a local matter, and that natural disasters and outbreaks of urban unrest are random events.”

("Reinventing Planning: A Position Paper developing themes from the Draft Vancouver Declaration for debate leading into the World Planners Congress," Vancouver 17-20 June 2006)

During our week long stay we participated in discussions on the theme: Orienting Urban Planning & Design: Practice and Pedagogy. Can professionals genuinely serve the needs of the poor? Can practice be transformed to address the realities of urbanization today?

There were many adjustments to make, the least of which was the change in environment from Johannesburg to Bellagio. I had to adjust to ‘wavelength’ of the discussions; it was not just about highlighting the problems but developing sustainable and viable ways of making design and planning professionals relevant to the creation of inclusive cities which cater for the urban poor.

We presented some of the projects we had done in Johannesburg and the lessons we had learned from the interdisciplinary studio model. We asked, can this on-site studio teaching be adapted in Universities as a mode of city building professionals?

As the week drew to a close, four groups were formed and each group discussed and proposed a number of ideas and solutions.

Group I: Pedagogy and Training

An Urban Innovation Co-Laboratory was suggested as a way to transform the knowledge base, educational pedagogy, and practice of all built-environment professionals, including faculty and students. This lab should be grounded in place, local political-economy, specific Environmental Issues

The lab projects should make a positive difference to the lives of the urban poor within the democratic frame. Pedagogy should create a committed, long-term cadre of young professionals, academics and researchers. It should offer bouquet of opportunities, including scholarships, study grants and other forms of longer-term support. In the short-term, existing networks of universities can be used to enter the education field. Institutional capacity in universities for research, teaching and action should also be developed.

Group 2:

Participants agreed that the essential goals of an education should be to sensitize and create awareness in the students while developing skills and instilling responsibility. Several systems to do this were discussed:

- Develop office skills & awareness through more integration of office practice in the education system. Bridging the Gap between students, the ‘real’ world & practitioners

- University DO-TANKS: in order to prove the value of education. Institutional departments should gather funding to hire fresh graduates to work in do-tanks. The work will be cross-disciplinary, guided by mentor(s), Large networks of do-tanks across the globe will act as an observatory & resource.

- Interdisciplinary studios

- Encouraging every university to have a resource bank to theorizing and developing skills in accordance to present issues of the city

- Including a compulsory project of ‘community service’ within the 4-5 years of education

- Professors should constantly update their theories, understanding and knowledge/lectures of local urban conditions.

Group 3:

We structured several strategies to directly influence and mobilize training institutions, directors of programs, practitioners, communities, government officials, civil society leaders and the private sector.

• People-based: Young Design Professionals Program

• Ether-based: World urban website –network node

• Place-based: Urban Centres –Regionally based resource centres that create a platform/ exchange for all interested people to dialogue, train, disseminate and act directly on sites

Group 4: The North-South Paradigm

To counter the growing distance between Private sector, Politicians, Planners and People, three types of network were suggested.

1. University/research network by institutes in the global south – international scale is key.

2. Forums bringing together researchers, civil society groups, bureaucrats, politicians and developers, media – city scale is key

3. Networks of community organizations engaged in practical action (sub-city scale is key)

The network should be formed around the principles that each network has a specific purpose, but it is the three working together that create the power for change. Funders need to guarantee independence of the networks.

|

|

|

Budoor Bukhari, American University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)