|

Christopher Herring: Sheltering Those in NeedSHELTERING THOSE IN NEED: ARCHITECTS CONFRONT HOMELESSNESSBy Christopher Herring Millions of people in cities across the globe dwell without a roof, and millions more without a home.[1] Despite the halving of global poverty in the past 20 years, more of the world’s urban population exists without an abode than at any other point in human history: on the streets, in encampments, and circulating within a variety of institutional shelters. Due to housing shortages, rural displacement, armed conflicts, and environmental disasters, rich and poor cities alike have to respond to a seemingly permanent population of those with no shelter of their own. The crisis of shelter in the modern metropolis is a social problem that necessarily invokes an architectural response. As co-founder of Architecture for Humanity, a non-profit solving design problems in service of the world’s porrest, writes, “If you strip away the ego, the archi-lingo, and the philosophies of design, the sole purpose of architecture is to provide shelter.” Yet all too often, the architecture of basic shelter is left to the poor themselves, who create or adapt ad-hoc temporary structures to guard against the elements, or else to bureaucrats whose designs do not address the needs of the homeless and displaced, but rather the housed and state officials who are often interested in quarantining the poor at the lowest possible cost. This year’s BERKELEY PRIZE Competition asks students to investigate the sheltering of those in need within their own communities from a different angle, by considering how architects might mitigate the suffering of the displaced by designing for the needs, desires, and interests of the marginalized and supporting efforts to abolish homelessness. [2] It asks students to consider architecture as a social art, which incorporates the social, political, and humanitarian context of design and its humanitarian possibilities. While the obvious structural solution to this query is the production of housing, until there is political will to realize it, our contemporary moment urgently requires temporary and transitional accommodations that provide more comfort than the pavement. It is from this liminal zone of dwelling, between street and home, that architects of the 21st century must sadly grapple with as the precarious, floating, and stateless factions of society who have no place to call home continually increase in cities across the globe.’ The most primitive and palliative architectural interventions are those at the street level. Architects are frequently enrolled by their corporate or government sponsors to defend spaces from those forced to live in public spaces. There are now hundreds of “anti-homeless” bench designs aimed at preventing those without shelter from taking a snooze, and “defensive architecture” has become a new vernacular derived from “bum-proofing” techniques that include concrete spikes, excessive railings, convex corners built into plazas, infrastructure, parks, and public spaces.[3]

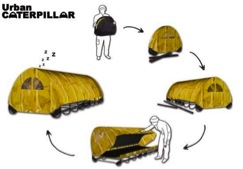

Some architects and designers have pushed back against this architectural policing, by assisting those in need with their daily survival in public space. In recent years, design studios and amateur builders have created hundreds of portable shelters that fold up into shopping carts, tents that fold out of backpacks, tiny homes on wheels, survival pods, and collapsible flame-resistant and water-proofed cardboard homes to enhance the livelihood of those living on the streets. Working closely with the Salvation Army in the UK, designer Amy Brazier discovered that while free sleeping bags were handed out by many charities, once wet they were nearly impossible to dry out, and that direct contact with the ground allows cold to permeate further. To reduce this exposure Brazier designed the “urban caterpillar” with waterproofed skin and raised platform, all easily transportable. Similarly addressing the plight of pavement dwellers in Chennai, Indian architects designed a foldable sidewalk shelter to provide a raised and covered sleeping area at night and a secure storage area during the day.

Despite this flurry of design in solidarity with those on the streets, very few have moved past the concept phase, and none have been produced on a scale to affect more than handfuls of homeless individuals in particular cities. This raises the question as to whether architectural interventions in public space, diversely labeled “Tactical Urbanism,” “DIY Urbanism,” “Guerilla Urbanism,” or “User Generated Urbanism” can have any significant impact on the survival of those in need, and if so, how? More frequently, architects and planners are employed by governments, charities, and NGOs to create institutional shelters and camps to accommodate homeless people. Although erected as emergency devices for the management of displaced people, and discursively justified as temporary necessities, camps and shelters have ultimately become durable socio-spatial formations. Official figures classify some fifty million of the world’s people as ‘victims of forced displacement,’ who largely reside in encampments. Refugees, asylum seekers, disaster victims, the internally displaced, the temporarily tolerated – categories of the excluded proliferate. Although most camps are driven by humanitarian responses, the camps put in place are often reminiscent of the logic of totalitarianism. This is in no small part due to their architecture and design. Propped up on sticks or draped over whatever can be found: a plastic tarp and a woven polyethylene sheet, blue on one side and white on the other, forms a makeshift shelter covering about 200 square-feet. This becomes a dwelling for four to six people. A cluster of 16 households makes a community; 16 communities form a block; four blocks are a sector; and four sectors a camp.[4] There are hundreds of such camps dotting the planet, from Afghanistan to Poland, Burundi to Thailand, in Serbia, Nepal, Iran, and Cambodia. Fenced in, surrounded by security checkpoints, segregated and located along urban peripheries, the camps dispense care, food, and water, but are also designed to control, filter, confine, and hide.[5]

Recently, architects have responded to this permanent emergency.[6] Architecture for Humanity in the US, Article 25 in the UK, Decolonizing Architecture in Palestine, and the Urban think-tank founded in Venezuela are among a new cohort of architectural NGO’s that serve as open-source design clearing-houses. They construct numerous projects, and provided research and consulting services to grassroots organizations and governments managing encampments. While there has yet to be an architectural paradigm shift in the construction of refugee tent cities, there have been scores of tiny projects and local endeavours to improve them. Alternatives to tent designs have been developed, such as the Buckminster Fuller-inspired U-Domes that are being utilized in Haiti; Ikea’s Better Shelters that are flat-packed and can be built in four hours without any tools; and the refurbished subway cars converted into shelters following the Szechuan Earthquake in China. At a larger scale, Turkish architects, planners, and policymakers piloted a new model of design for the Killis camp for Syrian refugees, with caravan households and firmer infrastructure. Some of the most significant innovations in the project were the inclusion of community features typically overlooked – street lighting, plazas, cafes, schools, and playgrounds. These architectural interventions not only alleviate the basic needs of shelter, but use planning principles and the creation of forms to facilitate practices such as education, recreation, and engagement, which in turn preserve a moral sense of self-worth through among residents and produce new forms of representation of camps and refugees beyond the static and traditional symbols of victimization, passivity and poverty.[7]

These same principles of supporting dignity through design can also be found in a number of homeless encampments in the United States. In over a dozen cities, homeless advocacy organizations have teamed up with architects to design camps, construct tiny homes, and help pass zoning legislation to create a more stable place than the street, and a more private, autonomous, and dignified space than institutionalized shelters. In Portland, Oregon, USA, Dignity Village partnered with architecture students at Portland State University to transform their illegal tent-city into a legalized eco-village comprised of personalized tiny homes. The village, which is self-governed by a board of elected residents, includes community gardens to harvest food, a shared kitchen to prepare meals, a library to study, and a community room for workshops. In designing the village around the principles of a social architecture, architects in solidarity with homeless people were able to create a sense of home, belonging, participation, and self-sufficiency lacking in more institutionalized settings.

However, most cities have increasingly turned to constructing shelters with congregate or dormitory style sleeping areas within larger complexes. When homelessness expanded rapidly throughout the Anglosphere of liberal welfare states of the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK in the 1980s due to economic restructuring, the rollback of social services, and the distintegration of mental health institutions, cities responded by constructing or converting existing buildings into emergency shelters.[8] Between 1984 and 1988 over 3,500 new homeless shelters opened up across the United States alone. Since then, the urban shelter continues to spread across new urban spaces where its had never existed previously because of the erosion of welfare states in continental Europe, the transition to capitalism in the former Soviet bloc, and the rapid urbanization of cities in the Global South. Like the refugee camps erected in the Global South that are intended as short-term settlements, but often persist for over a decade, emergency shelters in the Global North have also become institutions of the urban fabric, even as they remain in buildings never intended to serve such purposes. New shelters are, however, adapting. Since 2000, London has moved away from its congregate shelters and towards dormitory models designed for the specialized needs and lifestyles of its users, which include seniors, those with alcohol or drug addictions, youth, families, and women fleeing domestic abuse. Shelters are also now being designed to offer far more than just “3 hots and a cot”; a term coined by America’s transient workers in the 19th century referring to the bare necessities of a bed and 3 hot meals a day. Increasingly, shelters are designed as centres for coordinated services that include healthcare, counselling, education, and training to assist in integrating its residents back into society. The multi-service model is exemplified in Phoenix, Arizona’s (USA) Human Services Campus, which hosts three specialized shelters, a community and rec-centre, and six on-site non-profits. These designs also have their critics, who see campus plans as only further isolating and institutionalizing those experiencing homelessness. Furthermore, in a context of scarcity, shelter specialization inevitably creates unequal access and quality of accommodations for different groups of people, all too often reflecting the racisms, nationalisms, and notions of deservingness in a given society.

Designing congregate settings for vulnerable populations requires a unique social sensitivity of the architect. Berkeley Professor and architect Sam Davis helped design the Lark Inn, which provides shelter along with wrap-around services for runaway youth. In an interview on the project, Davis discusses how his design was informed by the social realities of homeless youth: Many homeless teens, runaway girls in particular, have pets, and they won't go to shelters unless they can bring their animals. So we included a kennel . . . The design had to be flexible. The center is separated into mini-dorms, because the staff wouldn't know from night to night what the population would be: how many boys, how many girls, how many people who would require more supervision. There's one kitchen for the center and everybody eats there. With homeless housing, particularly for homeless kids, the kitchen is a really important component. They’ve been out on the street and scrounging or doing what they call "survivor sex" for meals. Once they get into a stable environment like the shelter, we wanted them to feel that food is not a crisis; they can have it when they want with no hassle. They can just walk into the kitchen, open the refrigerator, and pour a glass of juice or help themselves to food. Also, the eating of a meal with other people on a regular basis is an important aspect of the socialization process.[9] Over the past decade, the United States, Canada, Australia, and a number of European governments have started investing in a “housing first” approach, building specialized housing units with in-house counseling, mental health, and medical services especially designed for those who have been homeless for years. Some of the most recent efforts have integrated high-design to de-stigmatize homelessness and either enhance poorer communities, like the innovative Star Apartments in Los Angeles’ Skid Row, which has the highest rate of homelessness of any US neighborhood, or to integrate the poorest into middle-class communities, like the La Casa Supportive Housing Project in Washington, DC. Such projects aspire to not simply mitigate homelessness, but end it, while taking into account the specific needs of the formerly homeless and their perception within the broader society.

In places, like rapidly urbanizing China and India, shelters have only recently become fixtures of the urban fabric. In China, temporary shelters first opened in 2003 after the country changed its punitive policy of police deportations of vagrants. In India, the spread of shelters has been much more rapid and in partnership with various grassroots organizations. In Delhi, India the Urban Shelter Improvement Board has established 231 night shelters that are operated by various NGOs, many of which are involved in broader community projects such as elderly welfare, mental health needs, and political action. One exemplary collaboration in Delhi between architects, social scientists, and community is the husband-and-wife team Rakhi Mehra and Marco Ferrario, who founded Micro-Home solutions. In designing and building two temporary shelters on the Yamuna River, they began the design process with social interactions with different homeless groups and undertook several night visits to see the operations of existing shelters, where no technical assistance of architects was considered. They found most of the shelters were made from tin materials that had zero insulation capacity, making them inhuman to sleep in. The structure was therefore built from a bamboo frame, with double walls made of canvas to provide an air cavity for insulation that adjusts to the extreme winter, heat, and monsoon climates. The false ceiling prevented winter dew and was adaptable to provide cooling in the summer. Their mission was not only to create improved shelter for some 160 homeless guests, but “to influence the local government models on the design and operations of homeless shelters.”

Despite some of these recent innovations in sheltering those in need, the shelters, camps, and streets, largely remain unsafe, unsanitary, stigmatized and unpleasant spaces that most often only entrench a person’s poverty and alienation from society. In much of the rapidly urbanizing regions of the world, shelter for the poor remains in an initial “emergency” phase and it is still largely unclear how architects can impact shelter and homelessness. It is in this context of material deprivation and impoverished design that this year’s BERKELEY PRIZE challenges students to confront homelessness in their own communities. The Call In light of the explosion of urban people without a roof or a home, how should architects respond? The displacement of people from their homes - whether it is born by economic or political oppression, violence of war, environmental catastrophe, or other societal inequities - is not a design problem. But as this essay has surveyed, architecture is a “necessary” component of sheltering the poorest, with a distinct ability to mitigate or aggravate the condition of homelessness for those trapped in its grip. This essay has indicated that there are also deeper questions architects must consider when confronting homelessness. More than merely reducing the suffering of the houseless through the basic comforts provided by good design, how can architecture contend with the strictures of poverty beyond humanitarian and ameliorative relief? Such answers will be found only when one considers design concepts broadly and with a social consciousness, when the architect or planner is willing to go beyond the technical considerations of building and attempts to use planning principles and the creation of forms to facilitate and even create new social institutions and situations designed to alleviate the social ills that lay at the source of homelessness. A failure to address these broader social and political question will lead architects to run the risk of legitimating sub-standard housing for particular classes of undesirables or support regimes whose interest is first and foremost to confine and invisibilize their poorest, rather than to integrate and empower them. One question you will need to address is how architects may work in solidarity with the group(s) you examine towards sheltering those in need in such a way that steps towards universal housing, sustainable employment, and a more just city—rather than an end-point or final solution that might result in the entrenchment and fossilization of marginality. Answering such questions requires us to take seriously the proposition that architecture is a social art. Not simply a matter of necessity (rather than a luxury), but as a contingent practice whose work is embedded in and implicated by its social, political, cultural, and economic context. Architecture as a social art implies that the architect is not only engaged with this set of interdisciplinary concerns that situates her technical skill, but that she is also intimately concerned with the community’s needs, struggles, desires, and the everyday life of those that her architectural interventions effect.[10] So as you approach this year’s essay, ask yourself how the work or space you examine is situated within the broader socio-political structure and how it conditions the limits and possibilities to the architecture of shelter. How are or how might architects in your community work in solidarity with grassroots organizations and those in need? What ways does the work being done in your community mitigate the suffering of those without housing? How does it politicize the issue? And how might architecture both assist in providing ameliorative relief for those experiencing homelessness while also working to abolish the conditions of economic deprivation, racism, and oppression that undergird it? Through these lines of inquiry architecture is rendered much more than a technical practice, but a social vocation that can help solve, rather than merely react to, the problem of sheltering those in need today. Notes [1] In the most recent global survey the UN Commission on Human Rights estimated that approximately 100 million people worldwide are without a place to live and 1 billion are inadequately housed (“Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living,” UN Commission on Human Rights, 2005). [2] Defining this year’s question proved a special challenge, as the meaning of homelessness is fluid and elusive, changing over time and between places. The prize committee decided that the basic parameters for this year’s engagement should both be flexible enough to include the wide-range of conceptualizations of homelessness in different cultural contexts, but narrow enough to focus architects on the oft-ignored issue of liminal dwellings that are “less than housing.” In short, how architects might address the immediacy of needs in a world without universal housing for the estimated 100 million who are without a place to live. For a global survey of the definition of homelessness see the United Nations Report Strategies to Combat Homelessness (Habitat, 2000, pp. 115-153). [3] For thousands of examples of anti-homeless design see Artist Nils Norman’s gallery, documenting defensive architecture over two decades. Also see Mike Davis, “Fortress LA” in City of Quartz: Excavating the Future of Los Angeles (Verso, 1992) of how these architectural interventions contribute to the militarization and carceralization of urban space. [4] See journalist and author Jim Lewis’ “The Exigent City” (New York Times Magazine, June 8, 2008) for an overview of the problems of camp design in the context of emergency urbanism and Mitchell Sipus’ article “The Problem with Refugee Camps,” on the challenges he faced as an urban planner at a refugee camp in Turkey. For an excellent macro overview and up-close examination of refugee camps in a global perspective see Michael Agier’s On the Margins of the World: The Refugee Experience Today (Polity, 2008) and Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government (Polity, 2011). [5] See sociologist Loïc Wacquant’s article “Designing Urban Seclusion in the 21st Century” (Perspecta Yale Architectural Journal, 2013) on the various functions and outcomes of urban seclusion in relation to ghettos, camps, prisons, and ethnic enclaves – all of which disproportionately host the homeless and displaced. [6] Even as late as 2001, few architects were concerned with designing for the millions of displaced persons. In the introduction to Architecture for Humanity’s 2006 book Design Like You Give a Damn, founder Cameron Sinclair recounts a story from the early days of the organization. Half-joking yet deadly serious, he describes the day when, while still running Architecture for Humanity from a single cell phone, he was contacted by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees who told him that the Architecture for Humanity was on a list of organizations that might be able to help a potential refugee crisis in Afghanistan should the US retaliate in the wake of September 11. “I hope it’s a long list,” says Sinclair. “No,” comes the answer. [7] Urban theorist, planner, and UC Berkeley Professor Ananya Roy has recently called for researchers to rethink subaltern urbanism: “writing against apocalyptic and dystopian narratives of the slum, subaltern urbanism provides accounts of the slum as a terrain of habitation, livelihood, self-organization and politics” (Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35.2, 2011). Might we then also rethink a “subaltern architecture” that could likewise challenge these narratives and representations through design that accounts for the habitation, livelihood, self-organization and politics of the houseless? [8] There are several books covering the growth of advanced homelessness in the US, but a classic is Jennifer Wolch and Michael Dear’s Malign Neglect: Homelessness in an American City (Jossey-Bass, 1994). [9] See Sam Davis’ book Designing Homeless Architecture that Works (University of California Press, 2004) on the intersection of personal, organizational, and design issues around homeless shelters. For a broader comparative perspective see John Rusell Graham et al.’s Homeless Shelter Design (Brush Education, 2008) which examines 63 shelters in 25 cities in the US, UK, and Canada combining the expertise of social work with architecture. [10] As highlighted in the introductory essay of last year’s Prize “Architects Confront Poverty,” collaboration between architects and grassroots organizations is not only more humane, but makes for more informed and impactful design. This principle was the focus of two recent exhibition Design with the Other 90%: Cities, mounted by the Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum in 2012, which presented sixty projects from forty countries that combine grass-roots input with professional support and Small Scale, Big Change: New Architecture of Social Engagement at the MOMA in 2011. Christopher Herrring is a 2016 BERKELEY PRIZE Juror and a doctoral candidate of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley whose research is on the restructuring of homeless regulation. Read more about Christopher here.

|