Faiq Mari Final Report

Faiq Mari,Teaching and Research Assistant

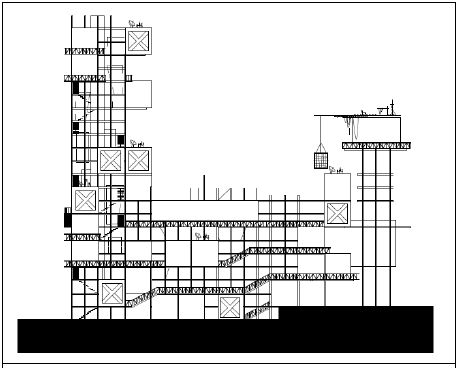

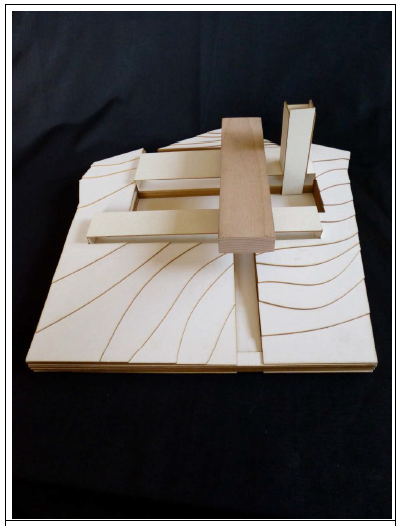

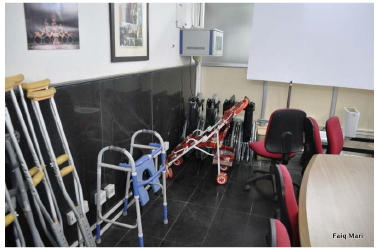

Intro One enters architecture school and starts losing sense of time and place. Too much work and too little time to pause and ponder of the real reason he/she is actually studying. As years pass by, one project after another, one starts to feel an increasing gap forming between (him) and (his) surrounding reality. This was at least my own experience. During my recent years as an architecture student, I have always felt a gap between architectural education and its surrounding context. It was often a very indirect relation that we had with the community we designed for, and under the many layers of theories and analyses lied a very limited understanding of the human we designed for. Seldom was it that architecture was seen as a tool of real change on ground. But does architecture have to be taught this way? My experience in my first year as a teaching and research assistant was my trial in answering this question. _______________________ Almost a year ago I was appointed a teaching and research assistant at Birzeit University, from which I had just graduated. Some months before that I participated in a competition that shaped the year ahead, the Berkeley Prize Essay Competition. The Berkeley Prize Essay Competition was an opportunity for me to delve into my deep conviction of architecture as a social art. During the process of writing my essay, which talked about disability in Palestine from an architectural perspective, I came to understand the importance of inclusive design, and the great power and responsibility an architect has in enforcing it. My conviction of architecture as a social art developed and solidified. The direction I would take as an architect became clearer. In my essay I had discussed the important role of education and awareness-raising in achieving the rights of the disabled. I had stressed the potential of architects and architectural education in this regard. As I was about to start my job as a teaching and research assistant I began to formulate a plan to apply this through my own career. In the following pages I will go through the past academic year, review its events and conclude with the lessons learned; eventually I will try to answer to question of the possibility of another teaching practice at my university. 1st Semester The moment I was appointed a teaching assistant I began thinking of ways to improve the learning experience and try to tackle the issues I have so recently been experiencing at my own university. I realised that I had no past teaching experience, but that I did have a five years experience as an architecture student and recent exposure to other facets of architecture through the Berkeley Prize; I decided I would base my efforts on that. At that time I had to think about my goal and the method to achieve it. My end goal, I thought, would be to instate UD as a main concept in the Architecture Department’s general direction. Although quite ambitious, I believed that this goal was worth the challenge. I saw UD not only as a necessity, but as a paradigm that has the ability to shift the whole teaching process into a more user-centric social approach, whether we are talking about physical disability or any other social issue. After asking the Berkeley Prize committee members for guidance, I laid out the major features of my plan. I would focus on a user-centric approach to design, in which end users play a crucial role. I would also work gradually on delivering the concept of universal design to students. I believed in incremental growth, and that results would be more convincing than concepts. My assumption was that if I commence by infusing universal design in the design courses I teach, anticipated success would be reflected in students learning outcomes and feedback and I would thus be able to convince the department of the importance of UD and a user-centric design approach. I started by talking to the head of department and the course instructors I would be working with in my first semester, and together we set up a plan for the integration of UD in the “Design Studio III” course. We agreed to start with a general lecture for the three sections of the course and give students related readings, afterwards each section would deal independently with the concept of UD. In our section, the course instructor and I began the course by asking the students to represent an intimate sensory experience of theirs with an installation or performance. The exercise was intended to strengthen the students connection and understanding of their senses and their ability to translate this understanding into design production. It was also meant as a challenge, to draw the students out of their comfort zone. I was impressed by the students’ work and interactions. For example one student, Dina Habash, made a rotating colour disc that represents a childhood drowning experience of hers. Another made an installation of chairs that reflected a childhood memory of a basement play-house. After this exercise and as the students started their first project, a residential building, we started to gradually introduce them to issues related to disability and to the concept of universal design. First we had a general lecture with Professor Azim Assaf from the English department, where he discussed his daily experiences in different spaces as a visually impaired person. Then the students were handed readings from the book “Design for Independent Living” by Professor Raymond Lifchez and essays from the 2013 Berkeley Prize competition. It was yet too early to formally discuss UD in the project, I thought, so we led the students in its direction by focusing on inhabitants needs and discussing disability in light of the project and the activities the students have experienced thus far. In the second project, a choice of an elderly house, a hostel, or a dorm, we tried to expand on universal design applications and from the beginning of the project we demanded that each pair develop their main concept with inclusiveness as a base constituent. By the time the students had set their conceptual designs, we held a session with Muhannad Al-Shaf’i -wheelchair user- and Shorouq Al-Shaf’i -visually impaired student- where we heard from them about their experiences, and each student tried to discuss and develop their design ideas with them. Students showed progress throughout the course. Sara and Dina, who worked on an elderly house, adopted the user-centric approach of design independently and from the start. Their work progressed from their personal interactions with the residents of an elderly house in Ramallah. Their focus on the elderly’s needs and lifestyle produced a space that they deemed naturally accessible and universal. Those needs included the psychological and the social, and therefore the design meant to invite the surrounding community and encourage building relationships between them and the elderly. The basic idea was that the elderly in this house should be an integral part of the village, just like any family in any other house. In this sense, the design had to be universal. Hind and Rawia, who designed a student dorm, took their inspiration from the “spirit of the site”. To them, the site in its untamed nature reflected “the sublime,” and thus their goal in the design was to reinterpret this sublime in the form of a building. They depended on an unfinished, unstable feel of the building, rough as a construction site. Their challenge was to deliver this feel to users of all abilities while ensuring their safety. The challenge was tackled through designing for all five senses, concentrating on material selection. Acoustic, tactile and aromatic design were key for delivering the design concept and ensuring the safety of the building.

Students from other sections achieved great results as well. In the elderly house they designed, Diala and George made their primary focus the needs of users and their wellbeing. Their “discovery” of UD came as an answer to the approach they took in the project. In their design they sought to create a serene atmosphere universal and inclusive in nature, with effortless circulation, simplicity in form and level distribution, and a central core as a base platform for the building. The design was meant to let residents feel at home in a personalisable social space and empower them through an “accessible design that promotes movement and discovery”. Natural landscape and green elements were another facet of comfort in the project.

At the end of the course students were able to turn in designs that adopted universality to a large extent. This was evident from the way they verbally presented them, especially as they explained the concepts and their translations. Although this focus was not sufficiently reflected in architectural drawings, I could sense a very positive impact on the students. My main goal for this stage was to grab and sustain students’ attention and conviction in UD, and at this point I thought it was achieved. India Right after the end of the semester, came a wonderful opportunity for me to visit India. I was nominated to represent the Berkeley Prize at the 2014 National Student Design Competition (NSDC) held by the School of Planning and Architecture in Bhopal (SPA Bhopal). The competition, titled “Inclusive Design for Cultural Interface in Pilgrimage Sites,” focused on the application of universal design in the Indian context. I was inspired by the NSDC and SPA Bhopal in different ways. I greatly admired the effort and importance SPA Bhopal had given to architecture as a social tool, evident through the competition and the (teaching) of the school. At the competition, I have seen a vast array of creative designs that handled their -social and physical- context exquisitely, and achieved inclusive environments for all users. I have also witnessed great determination and belief in socially responsible design, and great knowledge being transferred. Of the many things that drew my attention were the interactive learning tools employed by the school, such as the life-scaled bathroom and kitchen models. I was also inspired by the diversity of the indian culture and the means through which architects and architecture students dealt with the notion of ‘universality’ in this context. I was constantly reminded of Palestine, and tried to imagine similar ways with which to approach universality from our own local perspectives.

2nd Semester

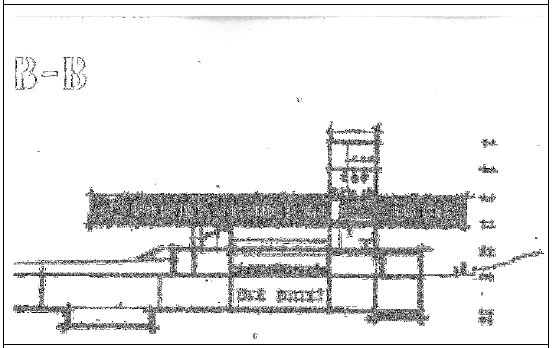

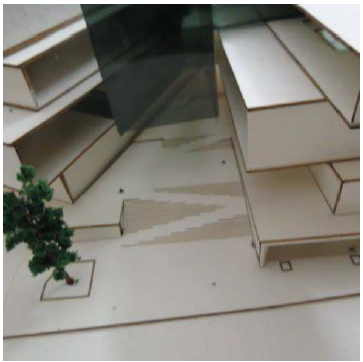

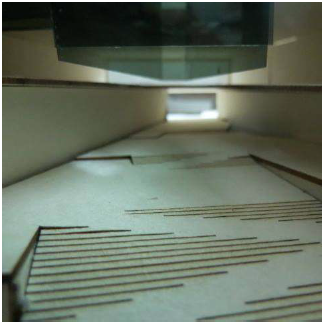

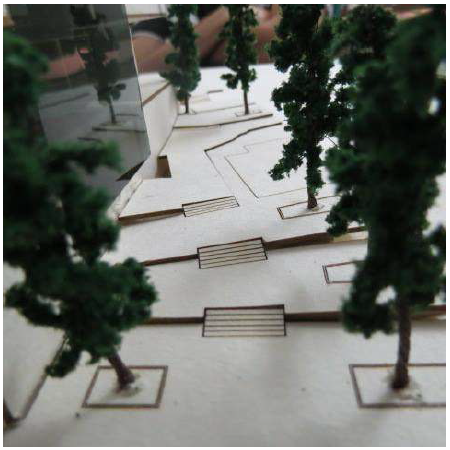

I was back from India with a refreshed mind and many ideas along with enthusiasm to continue on the same path in the new semester. Most of the ideas I had could only be applied in the long future and not immediately, but I was optimistic about the prospects of the current “Design IV” course. In this course, with the main project a public library, we approached the notion of universality through focusing on social inclusion. Throughout the studios we focused on the universality of the thinking process and designs, starting with the analysis phase until the final details. Students were always asked and encouraged to discuss their ideas with people whom the library would serve and put themselves in their shoes when imagining the space they are creating. By the last quarter of the semester we held a workshop with “Tanween” reading group, where students discussed general reading issues and discussed their projects with the group. Students were able to receive feedback on their designs and ideas and develop them further with the aid of this group of user/experts. Students focused on different issues according to their respective concepts. Yousef and Mahmoud, for example, aimed for an inclusive library that would be inviting to the people of the city. Located in the centre of the city of Ramallah, their library connected two streets via a path that passes through it, inviting people to have a coffee and read a book in its patios or just sit around in its garden and enjoy the free ebook service. The design was based on equal and unified accessibility of all services to all people of all backgrounds and abilities, and “this was the way it was meant to attract readers.”

Yet, this semester proved to be a challenge and an example of the tough nature of the teaching profession. Due to technical hinders, some of the activities did not go as planned. The workshop we held was supposed to be a bigger day-long workshop for the three sections involving user/experts from the reading group as well as the students with disabilities group, and it was supposed to be held at a much earlier date in order to give the students a chance to benefit from its results in their designs. Other user/expert sessions were planned as well, but unfortunately were not held. At the end, students were able to achieve good results given the conditions of the course. But again, the impact on students seemed to me more evident than their translation of it into architecture. This can be attributed partially to the fact that I did not set clear learning outcomes that the students should finish the course with, and partially to the predefined course requirements which did not allow the students to express their learning outcomes thoroughly in their final productions.

Student and Faculty Reflections But what about students’ own opinions? Since student and faculty conviction of UD was a major step on the way to instating UD in the curricula, their feedback is of utmost importance. Hind, a third year student whom I taught in the “Design III” course, confidently stated that she now thinks UD is “very important and should be integral to the design approach in every course and from its very beginning.” While her classmates, Sarah and Dina, had great appreciation of the user-centric approach generally undertaken in studio, and on which they have concentrated in their project: “We were able to connect our design approach to both our subjective interaction with the project and to the community it serves.” About all projects in general they said: “The result in our opinion was projects that were architecturally unique, yet profoundly in contact with their users.” The session with Shoruq and Mohannad and the discussion with Prof. Assaf seemed to have a strong impact on the students. Ramzi and Razi stated that it was a mind-opening experience that made them understand “how and why UD is more than abiding to minimum requirements.” While Hind and Rawia mentioned the impact the session had on their design, especially as they listened to Shorouq’s experiences of different spaces and materials. Yet, students also had their critical remarks. While appreciating the approach of the two courses, most students suggested that more focus should be given to UD and the user-centric approach. Most suggestions focused on increasing the frequency of meetings with user/experts -after all, we were only able to arrange one general discussion and one design session during the course. And while some students, like Sarah thought that what was done during the semester was good enough given the constraints, others suggested that we enrich the approach by focusing on UD from the early start of the course, integrating the concept and the user-centric activities with the course outline, and leaving the studio for activities that would allow better connection with the user/experts in the different spaces they use and in a non-academic context. One suggestion was to dedicate a course to UD, in order to allow a very comprehensive study of the concept and different applications. Students I taught in the second semester had similar opinions. Mahmoud expressed deep conviction in the approach undertaken, saying: “It is only natural not to separate our learning experience in class from society itself. Our design process should respond to society as a whole, with all its sectors including the disabled.” About the experience with Tanween group Mahmoud said that “personally it was very enriching. It was our first chance to interact with potential users of our designs, we were able to understand their own opinions, needs and perspectives. Their feedback was very encouraging as well!” Yousef, whom I taught in both semesters, agreed with Mahmoud in appreciating the user-centric approach and in his “deep conviction in Universal Design.” Of the session with Tanween, he said that it had a strong effect on their design. In their critique Mahmoud suggested a stronger integration of UD and the user-centric approach in the course description, and connecting with the user/experts regularly throughout the semester. He suggested more focus to be given to one-on-one interactions with the user/experts and even suggested dedicating a room in the department solely for that purpose. And while Yousef indicated that the first semester was more successful in addressing UD, suggesting more frequent user/expert sessions and field trips, both him and Mahmoud showed strong enthusiasm towards continuing with this path in the following semesters saying: “we will shoulder the responsibility of ensuring the success of this approach in the future … it has benefitted us greatly, and we feel that this is the way to go!” Through my observations, faculty members were also positive regarding the approach. I could see more interest being given to the user-centric approach and to universal design throughout the two courses. Previously, professors in the department did focus on disability issues, but form a rather technical perspective. From my discussions with professors including the head of department I could sense enthusiasm towards these new ideas and their prospects. By the end of the second semester the Head of Department, who was also the instructor of my section, decided that the department would instate UD as a main concept in all courses starting from the year 2014/2015 and that the department would encourage its faculty to adopt a user-centric approach where applicable. Conclusion So at the end, are there indeed other possibilities for teaching architecture. My short personal experience this last year tells me that there is. It also points out that there is also, room for change and acceptance of new ideas amongst faculty members, in spite of the many challenges facing such a change. It also reveals that students sense the need for a more social architecture, better connected to its context and to the humans it serves. This was evident through students’ enthusiasm towards the approach and their suggestions for upcoming courses, in which they demanded more focus on user/experts and universal design. What is next? The department’s decision to adopt UD in all design courses is the first institutional triumph in this endeavour. The following steps would be to ensure a healthy application. We will build upon this experience by sharing the experience of these two semesters with the rest of the faculty, discussing together the notion of UD and the user-centric approach, and developing a plan that would ensure the symbiosis of the different courses. On the most basic level, we should make use of the lessons learned from these two semesters and define specific UD learning objectives in each course as well as better integrate this teaching approach with the course outline and project deliverables. Reaching full integration of Universal Design in the general curricula of Birzeit University’s architecture department is not an easy task and will surely take time. This is the start though, and like an effort of two semesters started this change, a sustained collective effort in the coming years will achieve it. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|