Eve Edelstein Final Report

Eve Edelstein, M.S., M.Arch., Ph.D. (Neuroscience),EDAC, Assoc.AIA, F-AAA

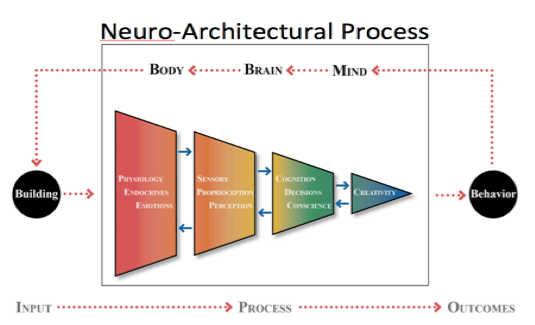

BACKGROUND:The study of both the mental and biological human reactions to built space are now subject to the scrutiny of science due to new opportunities borne of technological innovations. The evolution of neuroscience, and the use of emerging simulation and behavioral tracking technologies enable us to explore the neural bases for attributing value to architectural design, and to use such advances to develop principles that may be applied in design thinking and in practice (Edelstein, EA. World Congress Design & Health Journal, 2013). The fundamental synergy between architecture and the human sciences has recently been embodied in a ‘neuro-architectural’ approach, applying a practice-based process that utilizes a scientific process to relate the sensorial input of built environments to their bio-clinical impact (See Figure 1). Figure 1: Neuro-Architectural Process.

Legend: A flow diagram using a conceptual framework derived from the scientific method, links the physical stimuli of a built setting as the input to the responses of the body, brain, and mind, yielding behavioral output. A feedback loop between all elements represents the complex interaction between physical and human outcomes. (Edelstein, Eve A. “Research-based design: New approaches to the creation of healthy environments.” World Health Design Journal, October (2013): 62-67.) To date however, there are few who have entered the design profession with training in the scientific method or its use as a conceptual framework for translating biological research into design applications. A conceptual framework was presented to discuss many components of physical input that each design option modulates (light, sound, texture, dimension etc.), and the human reactions to those features in terms of the neural system that drive those responses (sensory, perceptual, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral). Architectural and environmental experts contribute to the definition of the physical features that comprise the physical stimuli to which the program, and people respond. Similar to an integrated project delivery processes, consultants (neuroscientific, clinical, physiological, and psycho-social specialists) should supplement the design team to search for and interpret the rigorous findings into terms that can be translated into design. Scientific consultants assess the reliability, repeatability, validity, and translation of such data into design principles. In order to generalize research into design, user/experts provide experience and guide priorities to identify outcomes and rank solutions that are best suited to serve the diversity of human outcomes. Modeled on evidence-based medicine, the use of rigorous data describing human responses to specific components of physical conditions provides a valid basis to explore the relationship between design and human reactions. Biological data offers a significant benefit as it forms the basis for human responses in all architectural types. For example, the perception of speech is determined by the physics, materials, and geometries of a space in addition to the individual’s clinical ability to hear, regardless of the architectural type. Beneath the layer of culture, biology and clinical data add to psycho-social observations to expose the fundamental interaction between people and places. The 7 universal design objectives serve as essential outcomes. Together, such data inform design hypotheses, and can be used to prioritize and rank the benefits and limitations of each design intervention. Together, this information focuses design thinking on the diverse range or ‘users and uses’ that each design decision must embrace. THE BERKELEY PRIZE OPPORTUNITY: The BERKELEY PRIZE Teaching Fellowship provided the opportunity to demonstrate that the neuro-architectural process could be merged with universal design objectives in an existing undergraduate design studio. A ‘Neuro-Universal Design’ curriculum was created for 3rd year design studios in tectonics (fall semester) and land ethics (spring semester), spanning the 2013-2014 academic year at the School of Architecture, College of Architecture, Planning & Landscape Architecture (CAPLA) at the University of Arizona, Tucson. The cohort comprised sixty-three Bachelor of Architecture undergraduates, six architectural design faculty and the Berkeley Prize Fellow a faculty member in architecture, planning and landscape architecture, who is also trained in clinical neuroscience, anthropology and architecture. In order to provide iterative and in-depth interaction, user/experts from the staff of the Disabilities Resource Center (DRC) at the University of Arizona and a faculty expert from the Interworks Institute, College of Education at San Diego State University joined in lectures, discussions, field trips, studio critiques and juries. Together, they represented user/experts with expertise in 1) design and architecture, 2) neuroscientific research-based design, 3) assistive technologies and 4) environmental equity. (See Acknowledgments.) A series of lectures by the DRC and invited user/experts discussed the philosophy and impact of equitable design. The concept that architecture can and should ‘flex’ to meet the continuum of human needs was introduced, in contrast to design philosophies that demand people ‘bend’ to built settings. The politics of design equity was highlighted, challenging students and faculty to consider for example, if the ‘poetics of stairs’ should supersede the ‘politics of space’. The disability resource faculty attended studios, mid-term and final juries, providing iterative feedback and insights to inspire equitable design, prompting students to consider the balance required in design for social equity. The practical application of these philosophical concepts were demonstrated in field trips and discussions at the University California Berkeley, the Ed Roberts Center, and the Center for Independent Living, during a field trip to California. Designers, clients and users provided valuable real-world perspectives and their experience and rationale for the creative, high-quality design that employed spaces and assistive technologies that supported equitable use. (See Acknowledgements.) COURSE CONTENT:

Semester One: A cohort of 63 students beginning their 3rd year undergraduate B.Arch. degree program. All students were required to produce projects representing universal design principles a) Techtonic Urban Design: Community transportation center and café Project 1 considered design of a transportation hub in downtown Tucson. Students’ deliverables included design boards, physical and digital models. The design hypotheses proposed were analyzed in terms of design input, human response, and desired universal outcomes. Annotated boards outlined the impact of design elements proposed. The students presented their conceptual framework, inquiry process, and design solutions to the faculty, students, and disability resource specialists in studio round-tables, conversations, and juried reviews. b) Urban High Rise: urban garden and community center that attended to tectonic considerations. Project 2 required that students create a multi-story tower in downtown San Francisco in the Embarcadero district. Site visits with the design faculty, DRC and SDSU staff yielded valuable opportunities for individual and group discussions about the challenges posed in an urban context. Students were challenged to seek imaginative solutions for equitable inclusion, engagement, and mobility within a multi-story complex structure. Semester Two: The cohort of students went on to complete their 3rd year undergraduate B.Arch. degree program. All students were required to produce projects representing universal design principles. a) Land Ethics & Arid Habitats: The program comprised a spiritual and educational campus in a natural desert habitat that respected land ethics and resource use. Project 3 spanned the Spring semester with a focus on ethical use of land and building resources. The assignment comprised of a religious and educational program set in an inaccessible and arid valley in a high desert plateau. Students were asked to focus on the phenomenological experience of this natural setting, to overcome the difficulty of gaining access during site-visits, and to propose a spiritual campus with equitable access in a rugged, hot, and potentially hostile climate. The site presented great challenges. The first issue was to ensure that all students and user/experts could access the site chosen for the project. The challenge that followed was inclusive thinking in order to create without excessive use of resources, spaces and interactions that were pleasant for all. The existing program focused the 3rd year studios on National Architectural Accreditation Board (NAAB) student performance criteria (SPC) related to technical design and responsible land ethics. Therefore, the neuro-universal content had to fit within the exiting course content. Discussions were reduced, and assignments were not graded. There was no reduction in work-load associated with tectonic or land ethics assignments, and the students were fully absorbed by the acquisition of skills, understanding and ability to produce their design projects. Although it was expected that the human-centered NAAB performance criteria were learned during the previous years, the students themselves reported that they had not sufficiently mastered the knowledge regarding codes and accessibility requirements, and did not feel ready to leap to address the breadth of neuroscientific or universal design concepts. Nonetheless, many projects demonstrated thoughtful design that addressed mobility in their first term projects. Many of the second term projects incorporated design solutions that addressed sensory and cognitive, as well as mobility issues. Students used neuro-architectural relationships to develop design hypotheses, and to articulate universal objectives. RESULTS:The students began to incorporate neuro-universal design principles in their projects as second-nature, assuming that all projects and places should offer equitable design. Surveys and discussion groups revealed how student attitudes changed as a result of the pedagogical strategies. A post-course survey was completed by the Berkeley Prize ‘neuro-universal’ studio after the academic year by 17% (11 of 63) of the students. Using a 5-point scale (Strongly agree = 1; Agree = 2; Neither Agree or Disagree = 3; Disagree = 4; Strongly Disagree = 5), four questions probed how students thought about design, and how the experience of the class influenced their thinking. Ninety % (n=10) of the students strongly agreed or agreed that “These experiences made me think about designing for people with a broad range of abilities.” Seventy-two % (n=8) strongly agreed or agreed that “These experiences made me think about how my senses, movement, emotion, and thinking change with design.” Eighty % (n=8) strongly agreed or agreed that “These experiences influenced the design of my studio projects.” Ninety % (n=9) strongly agreed or agreed that “These experiences will influence how I design in the future. Students revealed the benefit of both the neuro-architectural conceptual framework, and universal design objectives in their responses to open questions: “I had a much broader range of considerations after these experiences, I began thinking about all the senses and not just physical mobility or blindness.” “UD is no longer an afterthought… the goal is now imbedded into initial sketches…before any hard lines are drawn.”

REFLECTIONS:While surveys and design projects demonstrated their appreciation of direct interaction with user/experts, students felt unable to dedicate sufficient time or attention to the additional neuro-architectural assignments as well as their techtonic and land ethics assignments. Although the faculty acknowledged the value of regular contact and open discussions with user/experts, the there was little time afforded to conversation that would have helped students and faculty to ask the ‘hard questions’ or to break down barriers to understanding. Faculty commented that: “…some of the assigned [NAAB] criteria should have been lessened in order to facilitate integration of this [human-centered] curriculum in an easier way for faculty and students.”

“Even though it should be an inherent part of the design process, there needs to be a commitment beyond the superficial, … it is not a simple issue … of additional check box item.” A greater commitment to human-centered design in studio is essential. Pre-course workshops with user/experts should be held so that all studio faculty may become equally fluent in universal design. User/experts should also spend time in discussion and workshops to learn about real-world constraints on design. In addition, faculty recognized that undergraduate students, having completed only 2 years of study, may lack the skills necessary to graphically represent their passion for design that serves all users, or to verbally express the extent of their understanding of the continuum of human needs in built settings. However, they are not lacking in a concern for ‘empathetic design’. I have found that students in this course, and in all previous courses, have been open to design that meets the many needs of many users. It is up to their faculty and the accreditation process to ensure that their curriculum makes time for human-centered design. If courses cannot accommodate additional assignments, regular contact with user/experts in special lectures, desk crits, and juries will instill empathetic thinking. To encourage students to take on additional effort, a ‘Neuro-Universal Design Merit Prize’ was set up and judged by the Berkeley Prize Teaching Fellow and the Disability Resource team. The winner, outspoken in her passion and attention to universal design wrote:

“I may not be able to change the entire world, but now I can begin.” Finally, the Berkeley Prize Teaching Fellows should adopt the courage of their convictions. Despite the constraints encountered, the exposure to neuro-universal concepts resulted in a significant shift in student attitudes. Most rewarding was a comment from one of the students, a user/expert, who observed a dramatic change in his peers compared to his previous 2 years with the same cohort. “I can assure you that you have had a great impact on the way students think.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:The author gratefully acknowledges the Berkeley Prize sponsorship award. Many contributed to valuable discussions, studios, and field trips that exposed students and faculty to expansive and diverse thinking, including members of the groups as follows: Elaine Ostroff, Ray Lifchez, Ben Clavan, and the BERKELEY PRIZE Committee; Christopher Downey and students at the University of California, Berkeley; Bill Leddy and the Center for Independent Living at the Ed Roberts Center; Sue Kroeger, Amanda Kraus, Sherry Santee, Marisea Rivera, and guests, Disability Resource Center, University of Arizona; Caren Sax, Interwork Institute, College of Education, San Diego State University; Susannah Dickinson, Luis Ibarra, Bradley Lang, Darci Hazelbaker, Paul Reimer, Paul Weiner, Robert Miller, College of Architecture, Planning & Landscape Architecture, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|