Alan Birabi Final ReportA.K. BIRABI, PH,D., Senior Lecturer

This report is a reflection on my personal sense of the teaching experiences I gained on the 2013-2014 inaugural Berkeley Prize Teaching Fellowship for Universal Design. To me, it was a timely awakening of Makerere University’s Architecture School to contemplate re-modeling its teaching/learning methodologies and experiences so as to empower its graduates to be Universal design-led architects and social change agents. This is because it came to my realization that much as Makerere University has pioneered Uganda’s architectural education for the last 25 yrs, it has not adequately addressed accessibility, yet the profession is incrementally awakening about Universal Design. In this connection, for the past two semesters of the 2013-1014 academic year, Makerere Architecture School has been the laboratory for rolling out the pilot teaching and learning curriculum for universal design and accessibility under this Teaching Fellowship. This was timely due to the fact that Uganda is in the most heavily-impacted and minimally-serviced regions in the world, characterized by lack of knowledge, disinterest, and disregard for Universal Design. It further became apparent to me that Uganda’s level of public awareness about this issue is probably most challenging since it is a virtually top-down problem right from the upper political echelons to grass-root levels aggravated by centuries-old socio-cultural, egoistic and attitudinal injustices, demonology, and prejudices hostile to people with disabilities (PWDs). To date, most Ugandan cultures view disability as a curse allegedly emanating from witchcraft, maternal promiscuity or displeasure of the gods or some tribal or ancestral spirits and hence creating limited social acceptance of PWDs. Whereas statutes, bylaws, and regulations have emerged to ensure accessibility for PWDs in new buildings, rather, it is a haphazard legislative, regulatory, administrative, and planning enforcement regime infested with a network of corrupt officials who undermine adoption of accessibility in Uganda’s building industry. Taking stock of this one-year Berkeley Prize Teaching Fellowship, notable spin-offs include embracement of Universal design principles by my fellow Staff and students in studio design projects, and the students were very enthusiastic. Just how I proceeded to interest my students in the subject of Universal Design would perhaps be of utmost interest to other colleagues teaching in architecture schools since it was also somewhat challenging given the varied socio-cultural, ethnic, personality, attitudinal, gender, and aptitude backgrounds of the students. From my past teaching experiences and a wide review of insights in newer ways of managing the learning enterprise in design-based disciplines, I zeroed on the key principle of winning attention of the learners by continuously arousing and sustaining their interest. The wide review refreshed me and prompted me to assemble viable strategies: (i) the right controls on classroom psychology to support and strengthen fascination with Universal Design in each student; (ii) building harmonious working relationships with my students; (iii) confidence building; and (iv) a continuous focus on my role and that of the students. The wide review further empowered me to configure multiple motivational interactions with the students. In some instances I acted like a guide, a project manager, a facilitator, an assistant, a director, a friend, an auditor, a doctor, an editor, a patron or colleague as each oncoming teaching/learning situation warranted. On the other side, I caringly, thoughtfully, influentially, flexibly, humanely and persuasively made my students to become explorers, team workers, pupils, novices, friends, clients, patients, authors, protégés and colleagues on both ‘one-to-one’ or group teaching as need arose. Furthermore, I encouraged individual and collective skill-building for stimulating cognate innovations/styles, technical abilities, and imagination in Universal Design interventions among the students. Also, I utilized dramatic body language, humorous voice variations, inspirational eye contact, emotive facial expressions, and enthusiastic articulation of ideas. Come group work, I mixed gifted students with the less gifted in terms of designerliness, which awakened a high sense of academic rigour among both categories of students, a willingness to share ideas, and to attain the best from each other in each group. Incidentally, this strategic approach also captivated curiosity of every student. However, one of the challenges I faced was that the classroom composition was a ‘mixed crowd’ with wide visual disparities owing to the nature of Yr I admission to the architecture program. However, I endeavored to optimally create visual and designerly parity among them by non-discriminatorily offering extra ‘one-to-one’ attention to deficient students through ‘take home’ analytical drawing exercises from nature outside the conventional timetable. Despite stressing me, it yielded good results since the wide disparity between the two categories had diminished significantly as Semester II ended. Alongside individual bi-weekly projects, Semester II also included 3 group projects beyond classroom boundaries to build bridges with key stakeholders. The projects acted as mini demonstration projects to show glaring deficiencies of Universal Design and appropriate interventions of inclusivity. They also stood as contributions of the Architecture School to inculcate Ugandanization.

Looking back, I now realize that I may have been somewhat too ambitious for the kind of conservative setting in which I was executing the Fellowship. Thus, in terms of successes and failures, Project (A) dealt with a spot right at the heart of Kampala While some ramps exist at the spot, they were haphazardly constructed with uneven surfaces and gradients unfriendly to wheelchair users. So the idea was to do a ‘standard’ job about these mediocre provisions. However, the heightened security concerns over current terrorism trends could not henceforth permit photography in the CBD. This was one of the first unprecedented ‘failures’ the project suffered. Secondly, bureaucracy of issuance of a permit for the works was constrained by corrupt officials who expected some bribe while assuming that such a project was with huge donor money. As such, permission to carry out the project remained pending. However, the students learned to mold the ramps as seen in this photo. Project (B) explored signage for PWDs applicable to the built environment. The lift area of my faculty without a 3-button prompter for the blind (below left) became the demonstration project. The students designed its glass plate. However, it also suffered from legal constraints with the lift’s supplier.

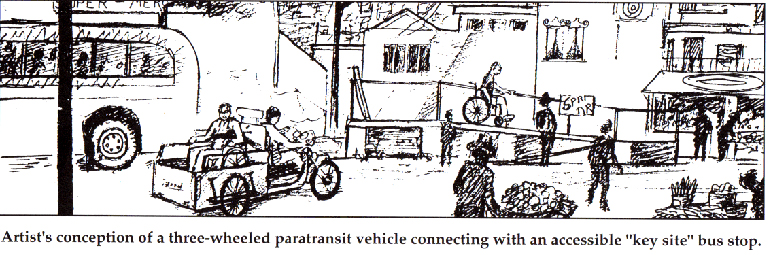

Group (C) designed and installed relevant signage and to designate the first ever parking space for PWDs on Makerere University Campus (photo on the right). Parliamentarians and City Authorities are scheduled to view it mid August as a sensitization strategy. The feedback on particularly the Group (C) was pleasing. It is my conviction that if the other projects had also succeeded, the same response of applause could have unfolded. From onset, while the project had envisaged engagement with user/experts, this did not work out as smoothly as planned. As such, the anticipated user/experts could not easily backfill their commitment of availability when the university re-opened. However, this does not change my conviction that a teaching program such as this needs to obtain updates, opinions, and/or feedback from user/experts in regular cycles so as to guide the ideals, objectives, and anticipated outcomes of the program. The category of user/experts was to include all Disability Persons’ Organizations, local city authorities, empathizers, professional bodies of the construction industry, etc. It is my hope that future mini workshops would bring on board the participation of all these groups into my teaching endeavours. The teaching of Universal Design positively influenced me to upgrade my earlier conventional means of teaching in the design studio. I look back over the one year and note with deep satisfaction a paradigm shift in me towards more creative, caring and thoughtful learner-centered approaches to teaching this subject matter unlike in previous years of a conventional outlook in teaching plain Design Fundamentals. I also seem to have learnt to be more flexible, less critical, more accommodative and eager to hear the views and opinions of the learners at their individual points of interventionist design. Furthermore, I gained greater insights of teaching Universal Design as one that requires adeptness in arousing the mental faculties of students to fantasize and turn those fantasies into achievable projects. I also came to appreciate the fact that teaching Universal Design requires giving requisite attention to every learner in their own right in order to fully unlock their potentialities. Apparently, while the two semesters progressed, other academic colleagues were keen to view the students’ work. As such, the outlook about the subject is very encouraging among both Staff and students. I was greatly encouraged by discussions from my colleagues in the architecture school and the realization that it is the sky that is the limit in teaching and learning about Universal Design. I have also come to appreciate that different levels of development among different nations coupled with varied technologies and affordability have tended to influence the types of Universal Design ideas that emerge. Given that Uganda’s built environment is far less sophisticated, this tends to reflect on the kind of Universal Design ideas that need to be addressed. Lastly but not least, continuity is the matter to be addressed. Dissemination about the subject will have to be rigorous via workshops, seminars, conference papers, and more demonstration. This would also require mobilization of necessary resources. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|