Ajay Khare Final Report

Ajay Khare, Ph.D./ w Rachna Khare, Ph.D. UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR CULTURAL INTERFACE IN THE SACRED SITE OF UJJAIN1.0 SUMMARYThe report is based on Berkeley Prize Teaching Fellowship at School of Planning and Architecture, Bhopal, India. This studio was one year long design studio primarily offered to the undergraduate students of architecture on ‘UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR CULTURAL INTERFACE IN THE SACRED SITE OF UJJAIN’. The studio focused on equal access to achieve universal design for a culturally rich site Ujjain in India.

2.0 BACKGROUNDUjjain is one of the seven sacred cities for Hindus and presents diversity in true Indian context. Apart from the rich tapestry of myths and legends, the city has witnessed a long and distinguished history with rich traditions. The city is a famous pilgrimage and visited by several people to pray for good health and well being, and a large number of them are vulnerable and deprived. This is also a site of mass Hindu pilgrimage or bathing festival called Kumbh or Simhasta. Our institute, School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), Bhopal, is an autonomous institution of Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. Supporting its Charter to be a socially aware institution, a multidisciplinary Center for Human Centric Research (CHCR) is housed at SPA-Bhopal. In accordance with its objectives, the CHCR conducted this design studio for Berkeley Prize Teaching Fellowship. The Universal design is not part of the regular curriculum in most architecture schools in India including our own institute. The subject like environment psychology, barrier free environment, man-environment studies, sociology are taught separately as theory courses and are remotely connected with architecture design studio. This one year long Berkeley Prize Studio provided us an opportunity to explore ourselves as universal design educators, and find a place in the existing pedagogy. We gratefully acknowledge the support of all faculty members and administrative staff, who showed their faith in us.

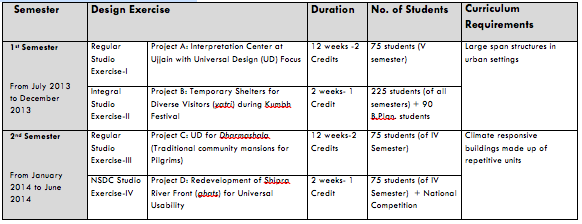

3.0 COURSE OUTLINE - STUDENTS, FACULTY AND CURRICULUMThe undergraduate degree program of architecture at SPA-Bhopal has ten semesters of six months each. In this one year long Berkeley Prize studio, four design projects (two every semester, one major and one minor) were conducted for Bachelor of Architecture degree students from July 2013-May 2014 (Table-1, Figure-1). To comply with the syllabus requirements, we made our universal design problems for each semester accordingly. We invited interested faculty members to make an in-house team. Other than them we had several multidisciplinary experts and user experts who visited us during the studio from time to time.

Table 1: Overview of the BERKELEY PRIZE studio

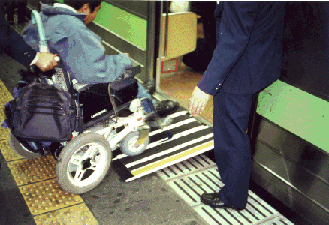

4.0 INQUIRIES AND OBJECTIVES In India, our preferences in higher education are so 'science' and technology’ focused, that it is difficult to motivate students to work with/for the community. When we started we had several apprehensions and larger questions in mind: Can universal design be taken up in an Undergraduate B. Arch. programme as a full semester course? If yes, then how it would blend with the existing curriculum and teaching practices? Where it would fall in our overall architectural design pedagogy which revolves around form, function & technology? How it would be taken up in a country where accessibility is just another theory subject and is not practiced by students as well as design practitioners? How it would be taken by the students and co-faculty members, education managers? How the studio would appear when seen in the national map of the architectural education? We were also not sure how universal design would look like India, would it be similar to our ‘borrowed from west’ accessibility guidelines or would be different in a totally different context? While universal design’s ‘independence for all’ focus is well grounded in western lifestyle of people living independently, what role does universal design play in India’s inter-dependent society where most people live with others? There are good examples of universal design in new construction; how can universal design be implemented in a culturally rich heritage site? With our questions, we formulated our overall teaching objectives other than objectives of the individual studio problems, they were-

5.0 STUDIO NARRATIVEThe two main highlights of the studio were, the engagement of multidisciplinary experts in the studio, and user centered approach for investigation and design. We engaged experts of history, theology, management, police officials, government officers, artists to interact with the students from time to time. The participating students were trained to conduct human subject research and also to analyze qualitative data from user study. They were also guided to connect the data to the design outcomes.

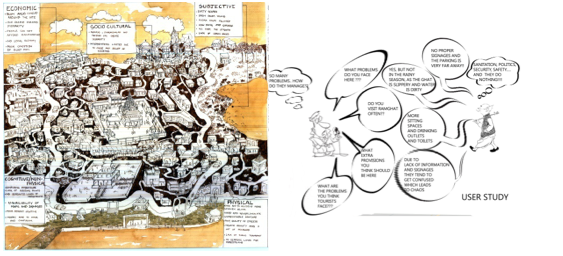

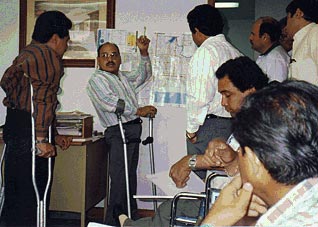

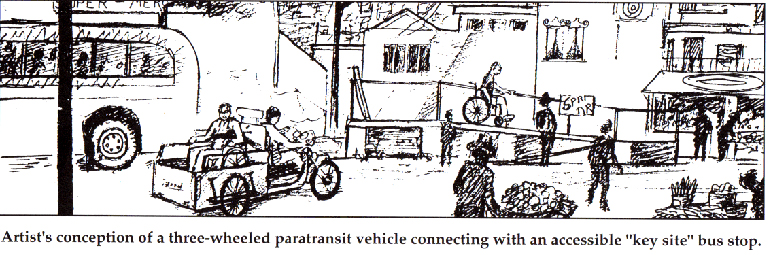

5.1 The First Semester In first semester, we introduced the concept of universal design as designing for ‘others’ who are different and are not known to us. We talked about diversity in Indian context and the unknown diversity that might be present in the rich cultural context of Ujjain. We also invited user experts to interact with the students in these weeks. The next week focused on the human centered approach to design. We taught them tools of ethnographic research for behavioral mapping and helped them to develop research tools for data collection. We also did a few lectures on Ujjain and its historic, religious and cultural context. After initial weeks of knowing the city, we all went together to Ujjain, the city in which we were supposed to design our studio projects. The students moved together in groups to understand the city fabric and to identify the social opportunities present in the fabric. They discovered that people visit the city for different purposes. They interviewed the diverse users including persons with disabilities, elderly, women, children, poor, non educated & rural populations, to understand these strong rooted beliefs, which bring them to the city (Figure 2). They tried to understand the associated rituals and different activities during the year.

The students were initially disappointed and disheartened to see the condition of the city and its people. The plight of weak and vulnerable was all the more disheartening. The traditional Indian way of life was mystic and far too cluttered for them. Gradually the ‘power of people’ started driving the interest of students in the studio. They started appreciating the city, its people and saw scope for universal design interventions. The students could see ‘Inclusive design’ as a mode to achieve ‘social sustenance’ in the Indian context. From the design for ‘life style’, they inspired to design for the ‘way of life’. In the first exercise they designed interpretation center and in second exercise they worked with intense interclass multidisciplinary groups on the site of Kumbh (Sacred bath). During pre-design research, the students interviewed about 40 people representing gender, age, abilities and socio-economic conditions (Figure 3). And later they made design solutions. The students produced innovative and empathetic solutions in both the design exersises. The solutions were people centric, contextual, inclusive and cultural, at the same time modern, futuristic and environmental friendly. We also realized that inputs from ethnography research resulted in enriched design thinking in the studio.

5.2 The Second Semester For this semester we had 2nd year students, who were even younger than the ones in earlier semester. It was further more challenging to teach the concept to them. We simplified and connected with them in much more informal way than the previous semester. With their curriculum requirement, they were supposed to work on climate responsive buildings, which helped them connect inclusive design to the larger body of ‘design ethics’. We started again like a regular design studio and planned it in a way that it connects with what is already known and practiced in a typical IV semester design studio. We realized that with so young students the formal and intense training of ethnographic research methods may not work so well as with the senior students in the earlier semester (figure 6). We planned that we would conduct an open ended design studio with a structure to keep them on track. To start with we identified important key words for our studio under larger umbrella of ‘architecture is a social art’. We then conducted lectures and training, and invited multi-disciplinary experts and user experts’ inputs in relation with the key words. Finally students developed their design proposals backed by pre design research.

We extended one of the design problems during this semester as a National Student Design Competition. We extended our studio theme ‘Inclusive Design for Cultural Interface’ to other faiths and other cities of India as ‘student competition’ at national level. Our students participated in the competition with other colleges. During the competition, we had a chance to compare the work of our students who worked with human centered approach with students of other colleges who were just given the design brief. Our students made ‘out of the box’ design solutions compared to others. Connecting with people brought innovation and compassion in the studio. Our students showed empathy, maturity, and at the same time their designs were reflective of the community needs and way of life. 6.0 LEARNINGS We had several moments of joy and sorrow in this one year long studio. Universal design is an abstract concept which cannot be seen and can only be experienced. It was neither easy to connect with the regular practices in design studio nor sustain students’ interest for such long time in this otherwise fashionable and elitist profession. The best moments were when we connected it with the existing prevalent knowledge, and to our surprise it was then welcomed with open arms. Some overall learning experiences are shared below:

When we started our studio we were not very sure that how students would be able to attempt 'Universal design' for such overwhelming diversity in India. The diversity where people have limitations of several kinds, like affordability, illiteracy, ignorance, unawareness, age, religion and social conditions like abandoned elderly. The students respected users for what they are, and interpreted universal design as a human centered approach to improve lives of all. Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|

Figure 1: Location of the four project sites in the inner city of Ujjain.

Figure 1: Location of the four project sites in the inner city of Ujjain.