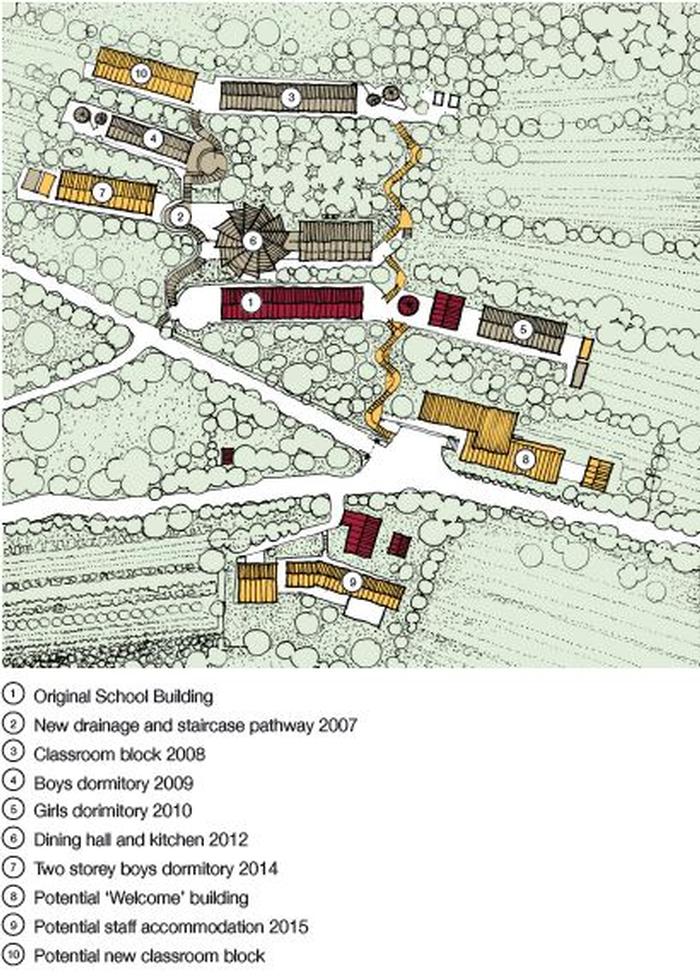

Benard Acellam EssayLearning on the Hillside: Confronting Poverty with Education“Poverty is like heat: you do not see it, you can only feel it; to know poverty you have to live through it” – Saying from Adaboya, Ghana. Here in Uganda, many people know poverty because they have lived or are living through it. To the Karamajong semi-nomadic pastoralists in the semi-arid North East, poverty means living without enough water for themselves, and their cattle. In a remote village in the West Nile region, poverty equates to an AIDS patient dying needlessly because of lack of access to anti-retroviral drugs. For a slum dweller in the capital Kampala, poverty means living in constant fear of eviction from city authorities. Regardless of the location where poverty plays a role in daily life, whether a rural or urban landscape, it always equates to unmet basic needs. So 10 years ago, in a rural community around Lake Bunyonyi in the remote South West corner of the country, education was identified to be the unmet need. In his paper ‘Communicating Architecture Manifesto’, Danish Architect Ivar Moltke writes that “the aim of architecture is for man to prosper, develop and contribute.” He adds that “the real value is neither found in the building alone, nor in the user by himself, but in the relation between an excellent building and the empowered user”. I visited a school in the Bunyonyi area to see how a group of architects are empowering a community by designing educational facilities. To evaluate the impact of this project within its context, I decided to put architecture (the project) on trial. The users and community around had the liberty to choose whether to be on the prosecution or defense side. I was the presiding judge. The trial begun. But first let’s see the precise background to this case. The year is 2006. There is not a single secondary school around Lake Bunyonyi. Very few children who can afford to leave the community to study in distant schools progress beyond primary level. Most youths simply lack employability skills. Many labor on menial jobs. For the girl-child, entrenched sociocultural attitudes dictate early marriages. Teenage pregnancy is rampant. Many girls end up inheriting poverty from their mothers. The pandemic of HIV/AIDS has hit the community, leaving scores of orphans and widows. The lack of access to educational opportunities leaves the community hanging at the mercy of ruthless poverty. In the words of former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, “Education is not a way to escape poverty - it is a way of fighting it.” In response, Lake Bunyonyi Christian Community Vocational Secondary School (LBCCVSS) was set up by four local Christian missionaries and led by Patrick Tumwijukya. The main facilities were one main classroom block with 3 classrooms and staff office, and 3 small dormitories (sleeping two to a bed, with triple bunks). The school is ill-equipped for the epic task. It struggled for two years. Then in 2008, a new chapter opens in the life of the school. Tish Feilden has worked with women groups in the Bunyonyi area. Her husband, Richard Feilden (RIP) is a senior partner of the architecture practice Feilden Clegg Bradley (FCB) studios based in Bath, United Kingdom. Richard Feilden Foundation has been created in his honor with the remit to look at the development of educational facilities in Africa, with Tish as a trustee. Through Tish’s contacts with Patrick, the foundation identify LBCCVSS as the next potential for their involvement. Architect Hannes Meyer writes that “Architecture is not an individual act performed by an artist-architect and charged with his emotions. Building is a collective action.” Richard Feilden Foundation does not do this single-handedly. They work with the local community, Lake Bunyonyi Development Company (LBDC), and the UK-based charity Buro Happold Trust. LBDC is a brainchild of Patrick, initiated in 1993 to address the environmental impact of farming in the area. Today it funds programs of ecotourism, agro-forestry, orphan-care, HIV/AIDS education, and a scholarship fund for area students. Buro Happold is an engineering firm also based in Bath, UK. FCB architects and Buro Happold engineers donate time and expertise to facilitate projects in the school. With that background, let’s proceed with the trial. I arrive at the school after winding along seemingly countless hills. This place is part of a vast hilly landscape that extends into Rwanda and South Eastern DR Congo. In wet seasons it is bitterly cold and its thin air can send the lung rasping and heart pounding. At the entrance, I pause, amazed by the magical view of the lake below, shimmering with the afternoon sun rays, reflecting the blue sky. Small and without fish though, nature blessed Lake Bunyonyi to be second deepest in Africa. The school campus is a cluster of buildings dotted laterally along the hillside, looking towards the lake. Central to the master plan proposal was the concept of sustainability through the use of concepts like flexible spaces to provide the necessary facilities with utmost economic efficiency. (Figure 1) I head to the principal’s office through a feature staircase with an integrated drain channel. Its pine-board risers are painted with the statements: ‘I love LBCCVSS’, ‘learning to succeed’. I learnt that these were done by students who participated in building the staircases. I was getting clues on what the students felt about their school, before talking to them. These stairs double as gathering spaces, sculpting beautiful moments in time for students who dare not dream of a better future. (Figure 2). At the bottom of the staircase flight is an underground rubble tank that collects the storm water from the drain channel. I climb up another staircase towards the classrooms and dormitories. Here I’m joined by a student called Victor. He was born handicapped and does everything with one hand. Being sixth born in a peasant family of 11 children, Victor says he was working at the school during holidays in waiver for school fees which his family can’t afford. With his physical condition, it is humbling to see the amount of cleaning- around he does. “My favorite place in school is my classroom” he says. We stroll past a recently completed 2-storey boys’ dormitory towards his classroom, while he shares his dream of becoming a teacher after school. Midway we meet another student, Arthur, who is fetching water from a large rainwater tank installed by FCB architects. The jovial Arthur is studying Building Construction. He says he loves LBCCVSS like he loves food. His favorite place in the school is the dining hall. “It is because food is served there?” I asked jokingly. We all laugh about it. “No!” he protests. “I like the way it was built.” The dining hall which is adaptable as a class room is dynamically and flexibly designed for use for assemblies, debates, village ceremonies, and community meetings. The most outstanding feature of this hall is the conical reciprocal roof which shelters the circular stepped hall. The hall is flanked by support spaces: kitchen, serving spaces and a storage space. With a capacity of up to 300 people, FCB architects designed the hall with the optimum use of local materials such as bamboo and eucalyptus in mind (Figure 3). Arthur wants to be an architect one day. The reason, he says, is because architects build nice houses like the dining hall, and earn lots of money. For the latter I could only smile. Talking with him humbled me on the impact the work we do as architects have on users. No doubt a building had captured the heart and mind of the youngster, birthing a career ambition. After a remarkable time at the school, I wanted opinions from the community around. Walking downhill from the school entrance, I stop at a homestead. The owner, Peace Akansasira has had six of her children go through LBCCVSS. For her, she says, the school is like another home where she goes for any help. The weekend before I visited, Peace had a give-away ceremony for her eldest daughter. Many relatives, friends and in-laws attended the marriage ceremony. “I borrowed chairs, plates and even drew water from the school to host my guests,” She says. Her gratitude towards the school cannot be expressed in words. From Peace’s home I walk further downslope to the serene Bunyonyi Safaris Resort on the lakeshore. There I meet Cosmas Mugabi. Cosmas joined the school in 2009 to study Tourism and Hotel Management. “Before joining, I worked at a stone quarry” he narrates. He was desperate. Fortunately, he was considered for Feilden Foundation’s scholarship for extremely vulnerable students. After graduating as a professional hotelier, the school found for him a job at the resort. A soft-spoken Cosmas is now manager of Foods and Beverages. From his earning, he sponsors two students at the school, and he is an instructor for the Tourism class. “That’s my way of ‘paying back the debt I owe’ the school,” he says. As a business, Bunyonyi Safaris Resort has partnered with the school to support farming in the locality. Their projects range from cattle rearing, piggery, to horticulture. Cosmas is one of many success stories from LBCCVSS. Every new building that comes up in the school seems to put a nail in the coffin of poverty in the community. FCB studios now plans to build another multi-purpose building. Their proposal for this facility was a finalist in the 2013 Open Architecture Network competition for designing adaptable hillside class rooms. They proposed a block of three classrooms angularly oriented toward a common focal point to which they could open out upon adjustment of wall panels. The three spaces are stepped to make construction across the site’s steep slope more cost effective. (Figure 4) In stepping the spaces, a cascade of staggered platforms was used and sized to allow small groups to meet separately, allowing a greater level of flexibility in teaching as well as a greater degree of individuality and privacy. Having heard from users and community around LBCCVSS, as judge, I have some reactions. Nelson Mandela said that education is the best weapon we can use to change the world, but like Mahatma Gandhi, I believe that there is a difference between education and literacy. In Uganda, we are over-focused on ensuring that children can read and write, instead of equipping them with practical skills. The educational landscape is now changing. The education officer of Kabale district said LBCCVSS is listed as a training center of the ‘Skilling Uganda’ program despite being a private institution. This is testimony that the school has won the trust of the education fraternity in the district. ‘Skilling Uganda’ is a flagship government program that calls for a paradigm shift in the country’s thinking towards business, technical and vocational education. FCB architects and partners could support the wealth-creation aspects of the school’s curriculum by designing a shop for vocational students to sell their wares and a café for tourism students to offer lunches and dinners. Designing with permaculture would ensure the school learns and lives off the land. This would augment the partner’s aspiration for a self-sustainable school, which is a big disappointment so far. Statistics show that Uganda has already surpassed the first MDG target of halving the proportion of the population living in extreme poverty by 2015, however undertones of extreme poverty is still easy to see. Besides, you cannot treat people as figures. To fight a winning war on poverty, architects must be determined. They must be resolute. They must do stocktaking on the ‘state’ of poor communities by analyzing the situations, conditions, and reasons for poverty. And they must be ready to make sacrifices: private profit, ego etc. Sometimes profits don’t come in dollars or pounds sterling or shillings. Sometimes it comes in lives changed. Above all, architects must work with the victims of poverty because therein lies the difference between success and failure. Combating poverty requires ‘boots on the ground’. Feilden Foundation could start exploring ways to impact the broader design community in Uganda. The publication of their “Uganda Schools Design Guide” has been spot on. This compilation of projects including LBCCVSS has been distributed to a range of organizations, including the Ugandan government, advertising experiences and best practices. More can be done. If I were in their shoes I would help develop the skills of local practitioners in Uganda and Rwanda where they are currently based, preparing them for a frontline role. This could be achieved by developing links with schools of architecture and partnering with local practices. From a design perspective, given chance, I would rethink circulation along the school’s steep slopes. The movement of the disabled and elderly ought to be assisted by the use of ramps or winding access ways of manageable slope instead of the current feature staircases. The inexistence of these features limits the disabled and elderly from participating in community programs conducted at the school. I would repeat the concept of using adaptable and scalable spaces which creates versatile learning environs. At the start of this paper, I took a position that poverty equates to unmet basic needs. In his book “Development as Freedom”, economist Amartya Sen agrees that poverty is caused by lack of access to basic opportunities and capabilities. These needs are universal, and not exclusive to any particular tribe, ethnic group or race. No one deserves the humiliation of abject poverty, not in a world more than eight times richer than it was 50 years ago. Eradicating poverty is a moral challenge for us all. As architects we claim that we did not know what was going on. Crystal Neff, who is chief editor of Rebuild360 magazine, a social movement for architects agrees that, “just as it is an incessant need to fill the ubiquitous gap between the world’s imbalances such as those between the wealthy and poor, it is our duty to advocate the power of design, and to serve a greater purpose other than purely designing for the sake of designing.” This is my final verdict on this case. Poverty has no permanent roots. Today, thanks to FCB architects and partners, LBCCVSS stands as a proud symbol of a community’s defiance against poverty, and its persistent, steady resolve to fight it. Architect Francis Kere who is famous for building schools in rural Burkina Faso once said that without education, development is a dream. Well, that dream is unfolding into reality around Lake Bunyonyi as the school continues to directly uplift the local economy and underpin the surrounding community. I’m now convinced that a quantum leap out of poverty is possible for Uganda if, as a nation, we own the mission of LBCCVSS, “creating skills for sustainable development”. Considering the level of poverty in the country, the efforts at the school may seem like a drop in the ocean. But to a student like Arthur or to a formerly desperate youth like Cosmas who has been lifted from nothing to something, it’s not a drop in the ocean- it’s life changing. Besides, what is an ocean but a multitude of droplets? References. Architecture for Humanity (Ed.), (2006), Design like You Give a Damn- Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises, Metropolis Books, San Francisco Davies, B, (2009), Lake Bunyonyi Christian Community Vocational Secondary School, Secondment Report, Buro Happold DFID, (2006), Eliminating World Poverty: Making governance work for the Poor, London, HMSO Ministry of Education and Sports, (2011), Skilling Uganda- BTVET Strategic Plan 2011-2020, MOES, Kampala Matt C, Ben S, A Guide to Planning and Designing Secondary Schools in Uganda, Richard Fieldden Foundation and Fieldden Clegg Bradley Studios, London Okoth, J. L, (2013), Adapting Community Centre Design to the Changing Needs of Rural Communities in Uganda- a Case Study of Kabale, Luwero and Tororo, Unpublished undergraduate dissertation, Makerere University, Kampala, pp 51-60 wa Thiongo, wa Mwiri, N, (1977), I will Marry when I Want, EAEP, Nairobi

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |