Hadiya Javed and Swaleha Javed - Fellow ReportABODE FOR THE VULNERABLE – THE FUTURE IS MODULAR

We were in the second week of the month of Ramadan, and I had just woken up for Suhoor (pre-dawn meal consumed by Muslims before fasting). I was unusually tired from the day before and wanted to sleep soon after hearing the Adhaan and performing my fasting Niyyah and Morning Prayer. While we were eating, my sister, who I teamed up with for this year's Berkeley Prize Essay Competition, screamed in excitement.

“Check your phone!” She exclaimed.

She often behaves like this when she has something hilarious or fascinating to share. I did not take her so seriously because my phone was away, and I did not want to move. But then, curiosity started to build. I grabbed my phone to check, and there was an envelope icon at the top of my phone screen. As I scrolled, I found an email that read, ‘Congratulations from the Berkeley Prize!’ I was so ecstatic to learn about our selection for this year’s BP Community Service Fellowship Award.

Ramadan is a sacred month for Muslims, in which we do something meaningful for our community, and this opportunity came in just at the right time. I thank the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley and Professor Raymond Lifchez for giving me this opportunity to assist ModulusTech, a social enterprise revolutionizing the affordable housing sector in Pakistan.

Widely viewed as a commodity, housing is predominantly a human right. The right kind of housing addresses health, dignity, safety, inclusion, and other community needs. It also responds to the global, generational, cultural, demographic, psychological, and environmental issues for a more inclusive and sustainable society.

During this fellowship, we were a part of ModulusTech's product design team for one of their ongoing community housing projects in Faisalabad, Pakistan, where the intended housing modules will be delivered. I was involved in the architectural design process, while my sister assisted in the survey process.

Through this opportunity, we got a chance to understand the housing needs and aspirations of the vulnerable communities that we had mentioned in our essay – the bottom 40% of population currently living in slums and remote areas – and work closely with the team of innovators who are making a difference in these people’s lives.

A detailed account of our activities is as follows:

WEEK 1: BRAINSTORMING OF IDEAS AND ADAPTING TO WORKING FROM HOME

Our first task was to brainstorm ideas for designing the housing modules. Mr. Nabeel Siddiqui provided with all the necessary information related to the project, including site details, master plan, and design brief. We spent the week studying this information and thinking of creative ideas for the project.

Because ModulusTech was working from home, we needed to prepare for the forthcoming Google Meet sessions as well, such as setting reminders, time scheduling, and record keeping.

WEEK 2: MATERIAL RESEARCH

After studying the project details, the next step was to search for suitable materials for this project. We set the criteria of material selection based on these sustainability factors:

This exercise brought my nerdy side to the surface as I browsed for academic papers and articles about new material technology breakthroughs happening globally and locally. The material research continued till we reached the design development stage, after which we culled through the list of our findings and narrowed down the possibilities that could work best for this project.

WEEK 3 to 5: UNDERSTANDING THE MODULAR CONSTRUCTION AND PROCEEDING WITH THE DESIGN PROCESS.

Modular construction process:

Before proceeding with the design process, I wanted to understand the construction process of modular buildings. Mr. Nabeel S. thoroughly explained the off and on-site building processes using the existing site documentation of one of ModulusTech's latest projects in Karachi. He also explained the financial process involving various stakeholders such as manufacturers, developers, builders, mortgage finance companies, buyers, etc.

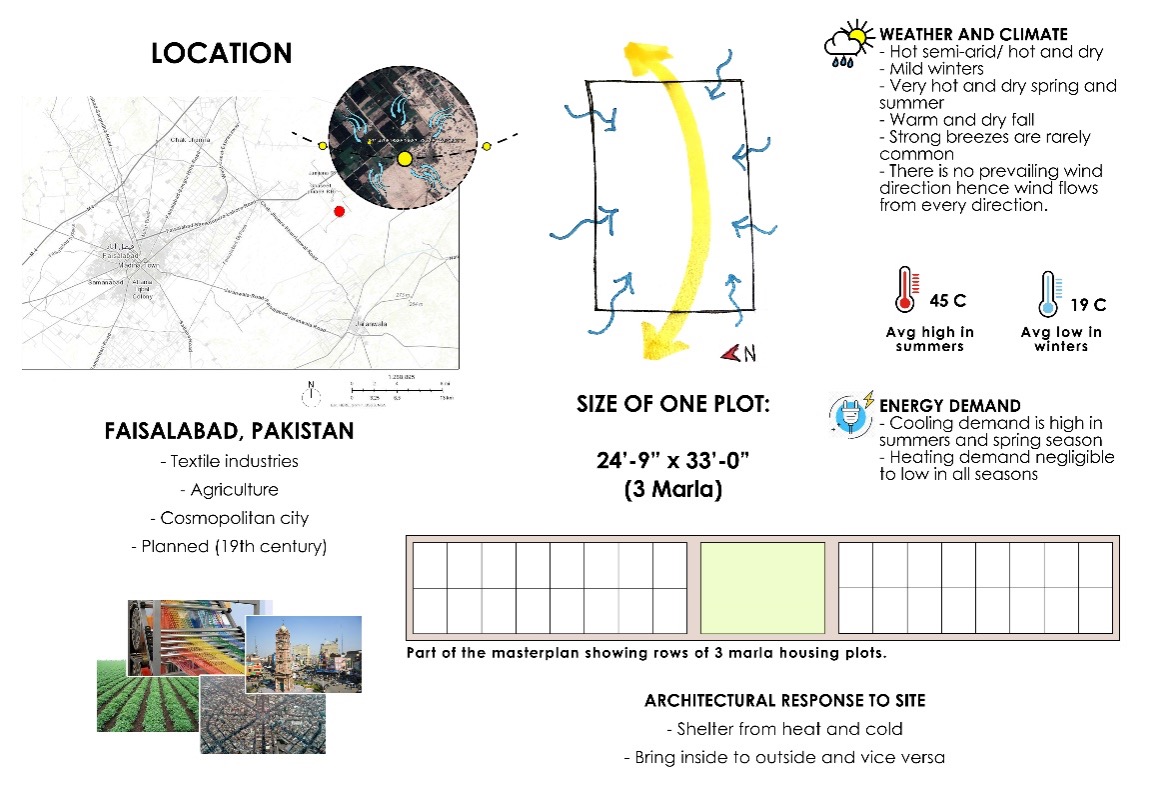

Furthermore, I got to learn about the IFC-EDGE Green Building Certification and an overview of the pre and post-construction stages, such as acquiring land parcels, obtaining construction permits, marketing and sale of units, infrastructure development and construction, quality assurance, and finally, delivery to the end-users. The design process starts: After acquiring the building process know-how, site details, master plan, and the design brief, my design process finally began with a site-analysis. The site: Site is in the suburbs of Faisalabad – one of Pakistan’s big cities known for its textile industries and agricultural produce. I used tools like Predesign and Google Earth to analyze locational context, wind flow, sun path, weather and climate, human and cultural factors, etc. to come up with suitable architectural responses to incorporate into the design

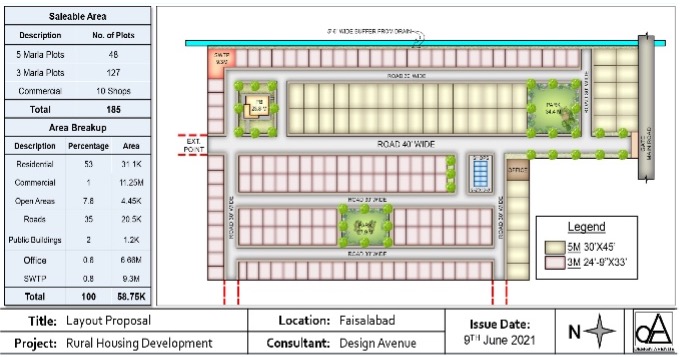

The masterplan:

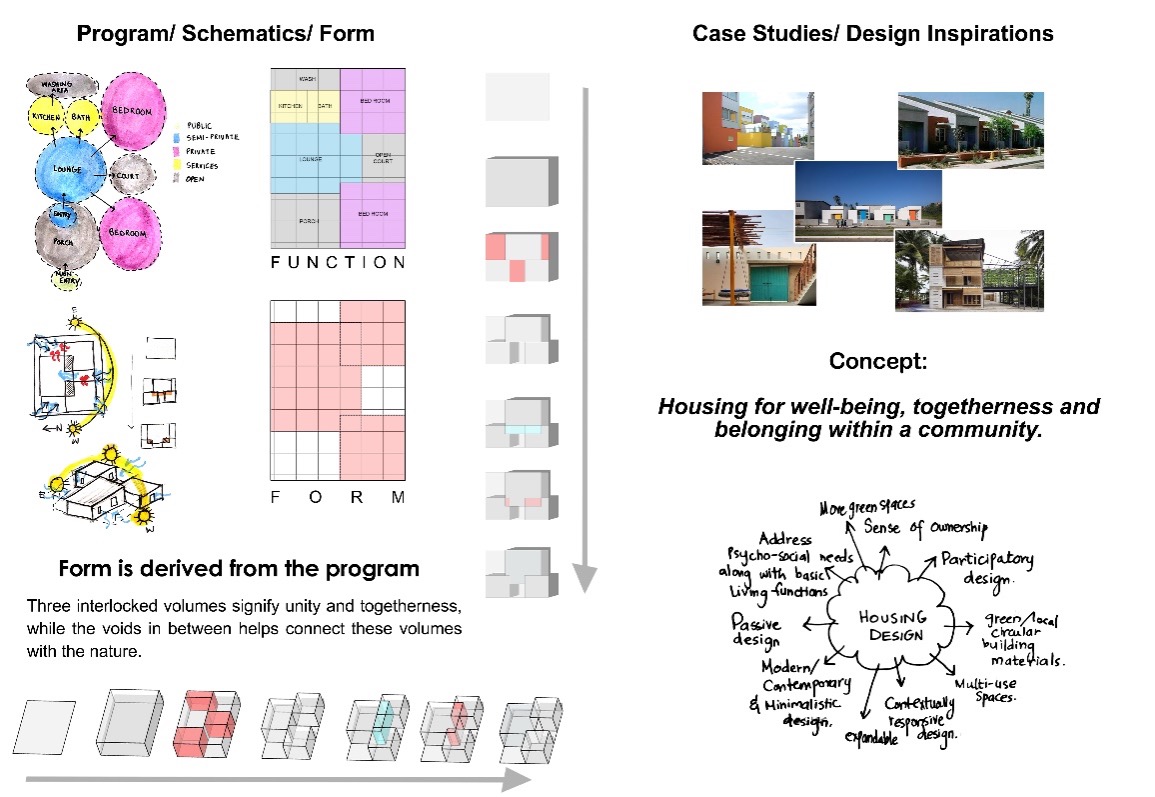

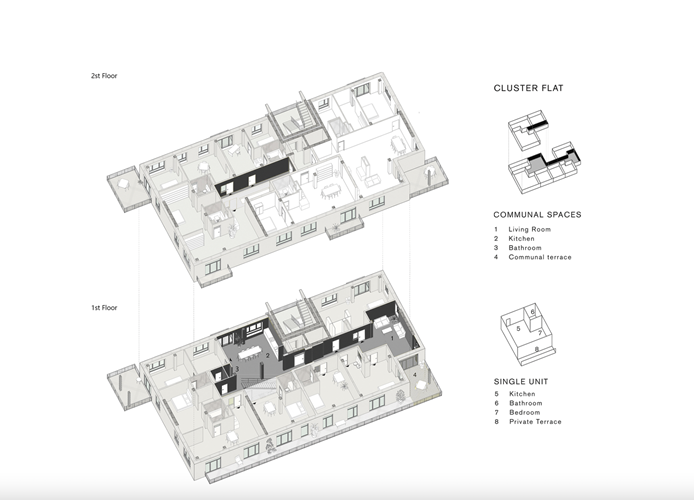

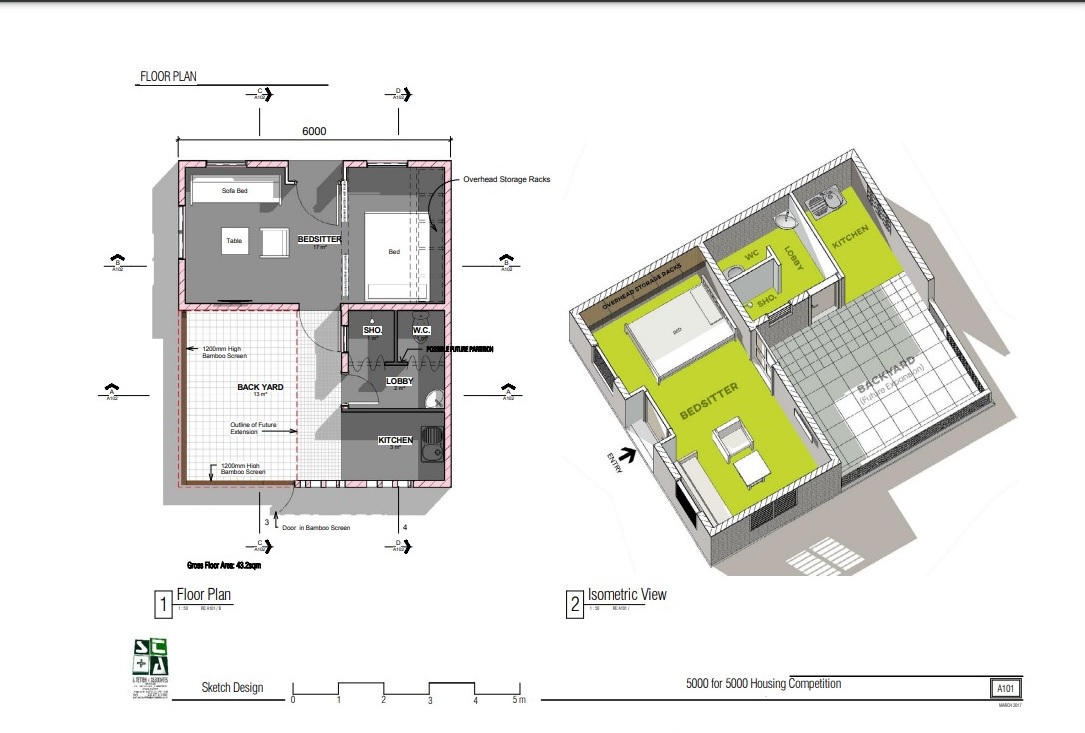

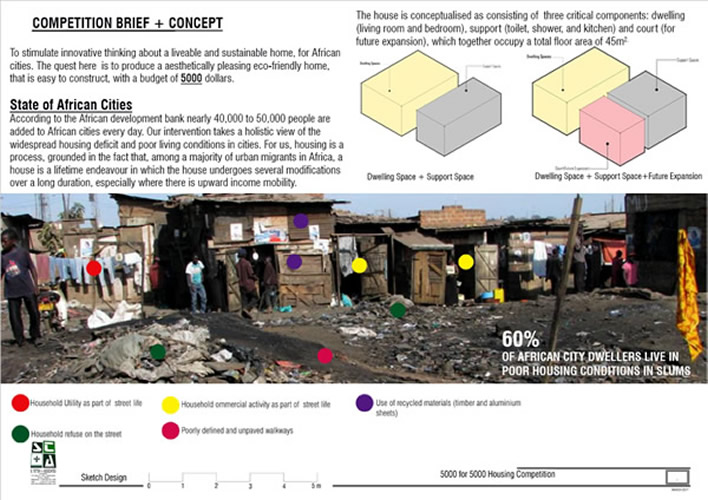

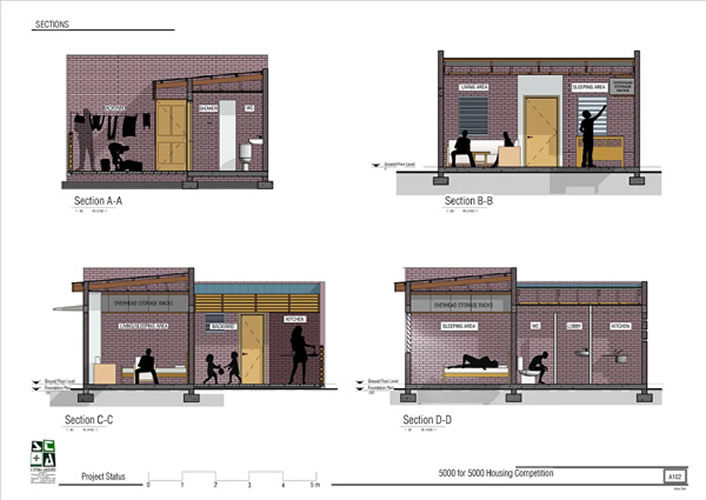

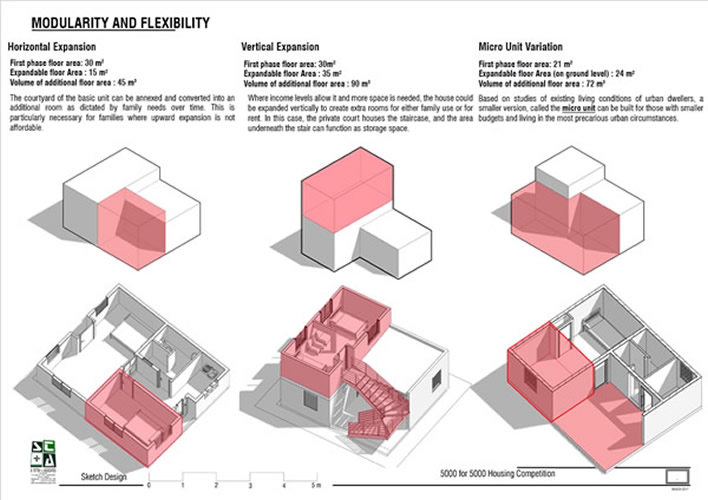

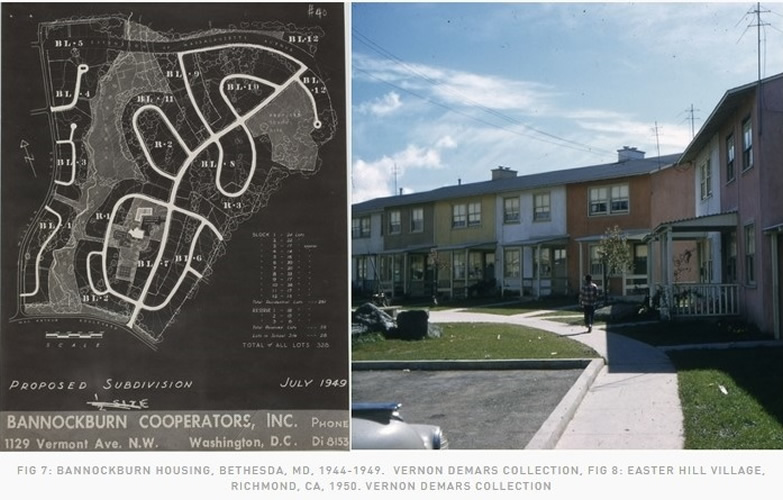

Based on a grid layout, the master plan features a gated community with provisions of 3 to 5 Marla residential plots for row housing development. In addition, there are recreational, commercial, and service facilities for prospective users. The brief: For now, my task was to design single-story houses on 3 Marla plots, which can be incremental/ expandable in the future. The program was to accommodate two bedrooms, a toilet, a kitchen, and a living room, along with a parking facility for a two wheeler if space allows, all while using passive design strategies. Design development and 1st stage design outcomes: Along with site analysis, I drew lessons from a few case studies (local and international) as well, which served as the foundation to begin the design process. The case studies helped develop the site program and design specifics, as well as thinking of the design from a psycho-social standpoint.

The design process led to initial design outcomes such as a concept, form, floor layout, an elevation, and a basic 3D model. I had to develop these outcomes further, after getting feedback from the client.

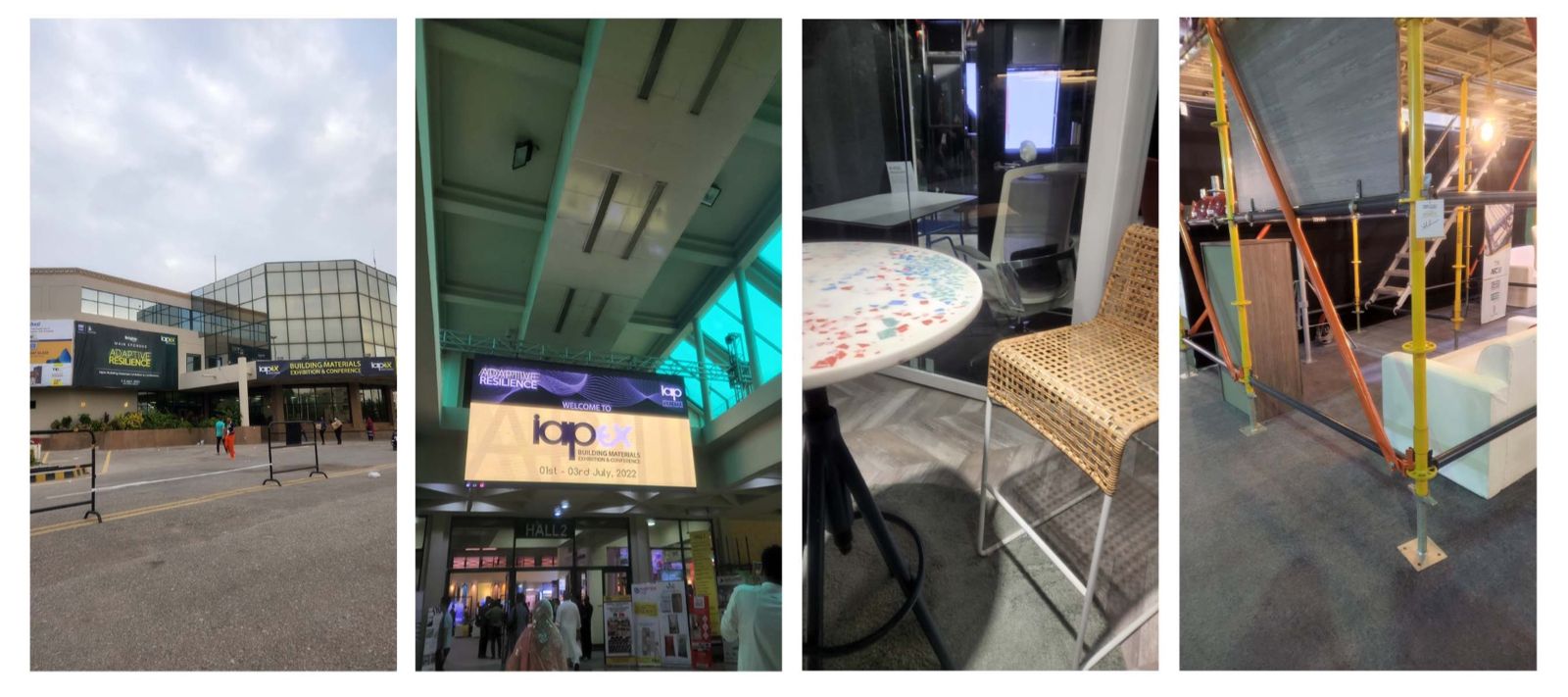

In the meantime, I visited a building materials exhibition organized by the local chapter of the Institute of Architects Pakistan (IAP) in Karachi, as part of the materials survey.

From this visit, I realized that not many sustainable and low-cost/affordable building material options are available in our local market. It was, however, reassuring to learn that a few local businesses were addressing the issue and determined to bring breakthroughs in this area. WEEK 6 & 7: DESIGN REVISIONS AND PROCEEDING TO THE NEXT STAGE OF DESIGN PROCESS After acquiring the client feedback, which was mostly positive, I began working on the design revisions. During this time, I worked on developing the 3D model and architectural drawings including plumbing, drainage, water supply, and electrical plans, and designed more options for the front elevation. Outcomes of this process were to be sent further for cost estimation and MEP consultants. 2nd stage design outcomes and sustainability factors in the design specifications:

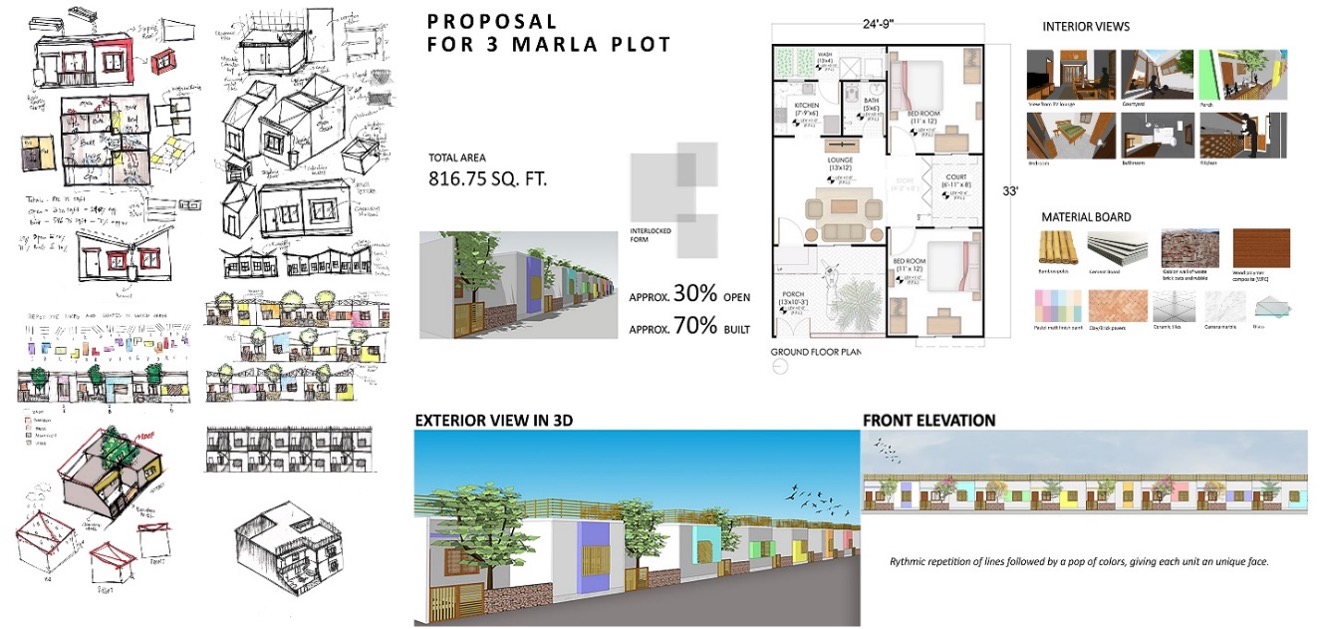

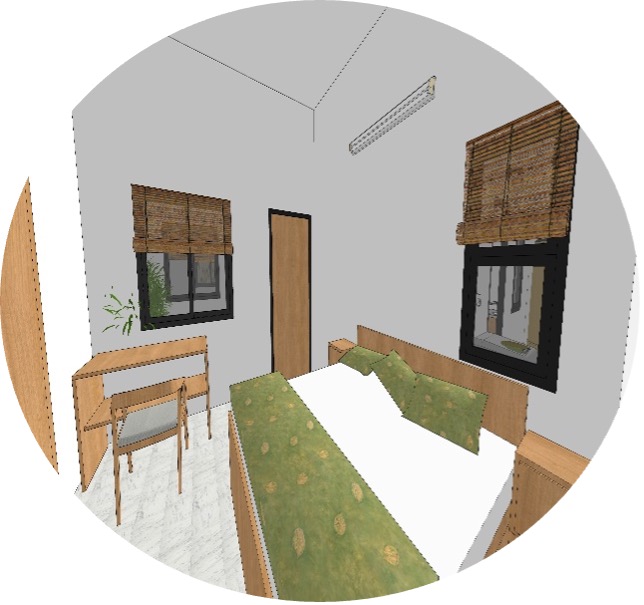

The floor plan includes two equally sized bedrooms, a kitchen, a TV lounge, and a bathroom. There are open spaces for various functions as well.

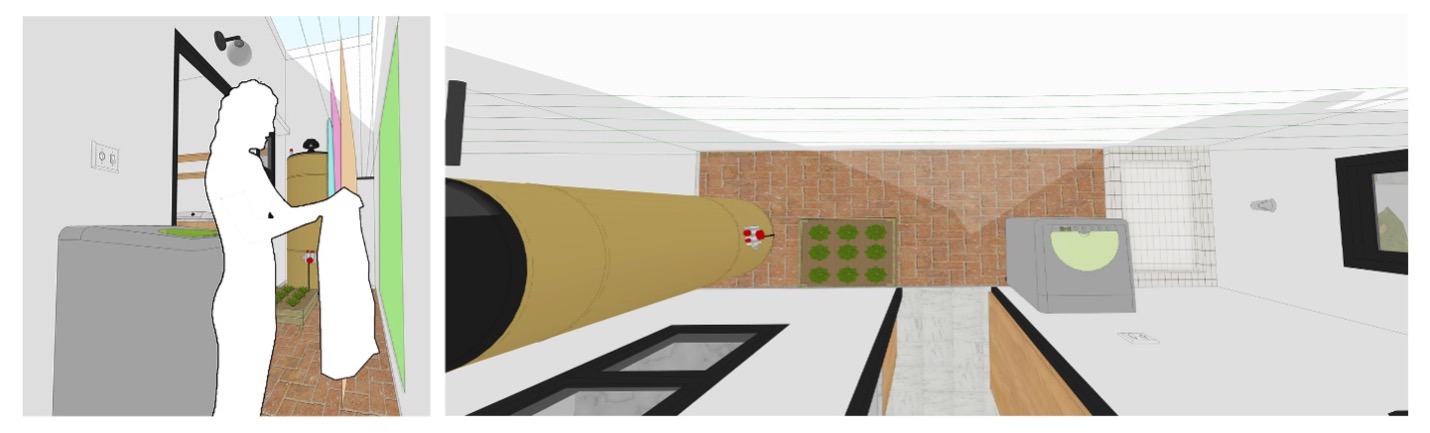

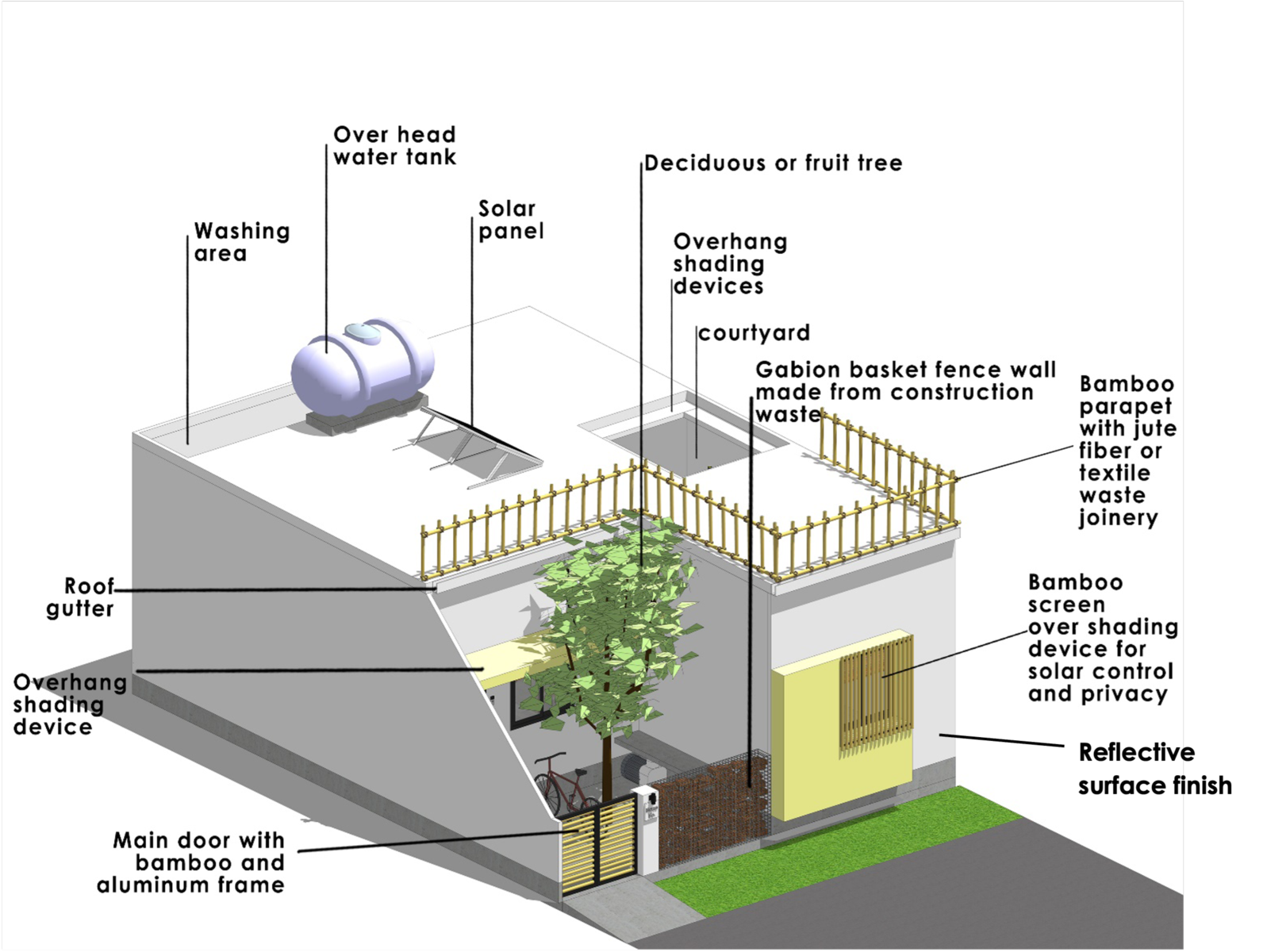

Open spaces: A single housing module contains three voids translated into multi-use open spaces, including a porch, a washing area, and a courtyard. The Porch is designed to be a welcoming space into the house and provides a parking area for a two-wheeler vehicle (a motorbike or a bicycle) and an outdoor space where children can play.

It also accommodates services like an underground water tank and a motorized water pump, concealed with a moveable slab that acts as a bench where users can sit under the shade of a tree. In the future, it can also accommodate a staircase leading to the upper stories if the owner decides to expand the house. The washing area facilitates cross ventilation in one of the bedrooms while accommodating services like a geyser, laundry space, and a small area for a kitchen planter where users can grow their own food.

The courtyard facilitates natural ventilation and light while acting as an outdoor living space where various household lounging activities can occur.

2- Building materials: After careful research, we shortlisted the building materials based on our selection criteria. The materials are locally available, affordable, modular, and circular, with minimum environmental impact.

Since the house is compact, light colored/reflective surfaces in the interior will create an impression of spaciousness and illumination.

My proposition to the users is to consider modular, cost-efficient and eco-friendly interior components such as furniture, window screens, and rugs made from bamboo because presently, furniture-poverty is another pressing issue in housing.

3- Passive design: Overhangs and bamboo screens are the shading devices for solar control. Light colored exterior surface finishes reflect the incident light back, while ModulusTech's insulated panels keep the interiors cool. The users can plant a deciduous or fruit tree in the porch area, which will not only filter the air but also act as a shading device during blistering-hot summers and springs of Faisalabad. Open spaces and operable window and door openings facilitate natural light and cross-ventilation. Each housing module is provided with a solar panel which enables it to function off-grid. In addition, the proposition is to use energy-saving LED lighting fixtures for energy efficiency. Roofs are provided with gutters to facilitate rainwater harvesting system. The proposition is also to incorporate a grey-water reuse system for toilets and watering the plants.

4- Psycho-social wellbeing factors in design: We experimented with various permutations in the facade of each house in the row so that each dwelling module would get a unique front elevation. The motive behind this is to evoke a sense of ownership and embrace diversity within the community. We played with different design elements, such as lines, shapes, and colors, with repetitions and rhythm to create attractive and distinctive elevations for each house. Colors play a significant role in the human psyche and behavior. Carl Jung’s theory of color psychology implies that they have a powerful impact on the human mind and well-being. Research suggests that colorful surroundings boost happiness, productivity, and creativity.

“Colors are the mother tongue of the subconscious” - Carl Jung.

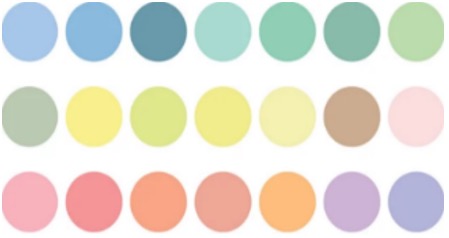

For exteriors, we have chosen pastel color pallet due to their light, soft, pleasant, and calming effect. Pastel colors are a combination of primary or secondary colorswith a certain amount of white, resulting in a shade that makes them bold and soothing at the same time. The building materials also seem to complement this versatile color pallet. In addition, our proposition to plant vibrantly colored deciduous and fruit trees can also add a pop of color in the surroundings

The 2nd stage outcomes are also to be shared with the community to know their opinions and preferences on design.

WEEK 8 & 9: UNDERSTANDING THE USER COMMUNITIES AND THEIR HOUSING ASPIRATIONS – ‘THE BOTTOM 40%’: This year’s Berkeley prize theme: ‘Design guided by the client’s needs – applying social factors research to architecture’ – suggested that as architects, we must first understand our clients, their needs, and their aspirations. A participatory design process allows to include the users in the design process by getting their opinions and working on the design, keeping their desires in mind. Hence, as part of the design process, we created a Visual Preference Survey (VPS) for the prospective user group i.e., people from the bottom 40% of the population, to record their preferences for the spatial layout, exterior design, and building materials used in the design proposal based on their visual perception. We will use their opinions in developing the modules further. Since I couldn’t travel to Faisalabad, I chose to visit a local neighborhood in Karachi, where we could find our potential user group, to understand their housing design aspirations. One of the main objectives of this survey visit was to create awareness about the ongoing climate-change crisis and the importance of incorporating sustainable lifestyle choices, such as using circular building materials and considering affordable modular and climate-smart housing solutions. Some of the questions asked in the survey and lessons drawn from them are given as under: - Demographic information such as occupation, average monthly household income, nature of income, number of children, adults and elderly in the house, age group, number and type of vehicles owned, etc. Majority were daily wagers and monthly salaried, and each household had at least five family members dependent on one bread winner.

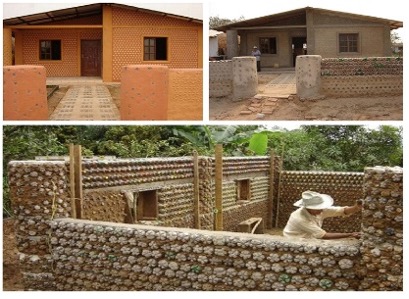

- For Material preferences, we showed them images of demolition waste (rubble and discarded bricks), plastic waste, textile waste, jute fibers, wood waste, preloved building hardware, and bamboo poles. We asked them if they would like to use any of these materials for their house, to which the majority disagreed.

Later, when we showed them the images of some contemporary buildings constructed with these, all responded positively. It shows that we need to normalize using circular building materials and create awareness on their sustainability factors in our local context.

- For their opinions on the housing modules, we showed them the plans, elevations, and 3d views of the interior, exterior, and open spaces to ask them if they were satisfied with the design specifications. We asked about their preferences such as the type of toilet and whether they would like to use bamboo furniture. The majority preferred squat toilets, and many were initially reluctant but later agreed to the idea of using bamboo furniture as we explained its eco-friendly and modularity aspects. We showed them two elevation options, with and without colors. We received mixed reviews on that, as a few wanted liberty in color choices while the majority preferred to have colorful surroundings and unique exterior elevations. The general feedback was great, and the people liked the design. "Building homes is about creating a sense of belonging, about participatory involvement and the expression of aspirations, relationships, and desires." B. V. Doshi

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|