[ID:787] To Create an Enabling City, Start with the StreetAustralia Close your eyes and stand still in the middle of a busy street. We are on Swanston Street, the busiest street in Melbourne, on an urban vista along which the world’s largest tramway network operates. It is a straight street so long that it melts into the horizon. On its sides are the umbrellas of immaculate café’s, red and yellow in the sun. Breathe in the fresh and crisp open air of our public plazas. Shop windows display new merchandise. Lush trees punctuate their way into the distance, and in the cool of Autumn their deep greens give way to pink and golden hues. Further down, the street meets the Yarra river, and the Yarra river meets a beautiful park. Where you are standing, you hear the hustle and bustle of street life: a horse-drawn-carriage drawing closer, babies, bells, and bicycles whizzing past, street musicians, and children running amok. If you had a physical disability, would you feel disadvantaged or empowered?

During our lives, we all experience times when our ability to go places is compromised. We might be pushing a pram, or carrying shopping; we might be prevented from walking down the street in heavy rain because it is too slippery. Just the other day my mother, arriving at Melbourne's Tullamarine Airport, slipped and fell in the middle of the road with 30kg of luggage, and consequently took some time to pick herself up. Some of us have impairments that reduce our abilities of movement or sense, and some of us might be temporarily or permanently unable to achieve a full range of motion. It has been recognised that people with disabilities face difficulties in travelling, and this can be associated with limited life opportunities (Morgan, 1992). The medical model of disability proposes that a person with a disability is handicapped by his or her impairment. As an architect, I believe in the social model of disability: that it is the environment that handicaps a person (Oliver, 1983).

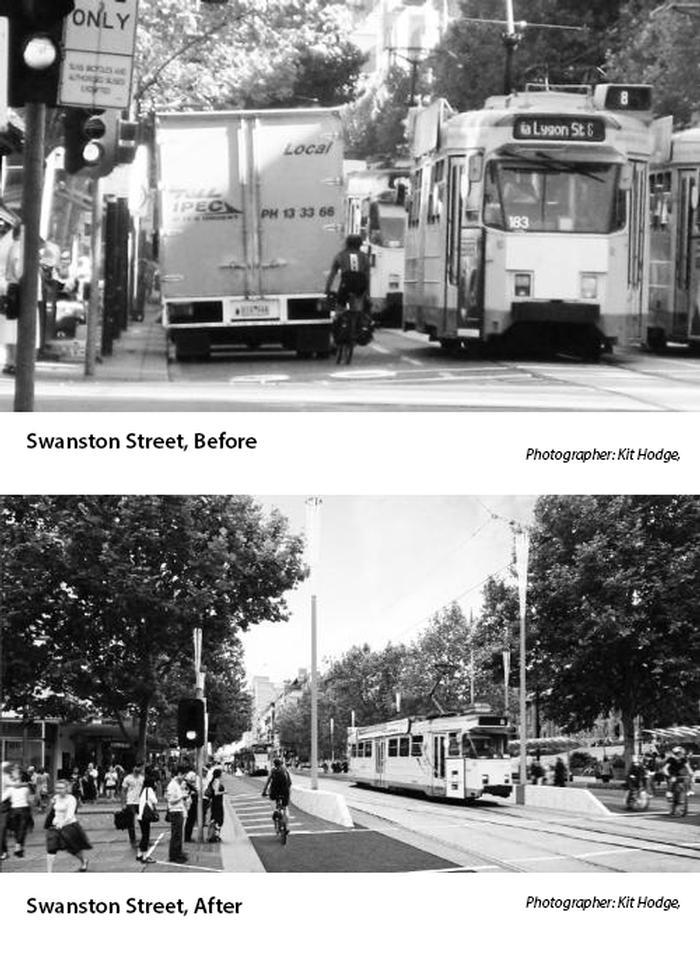

In 2011 and 2012, Melbourne was ranked the world’s most livable city in ratings published by the Economist Group’s Intelligence Unit. In the latest ranking, Melbourne was awarded 97.5 out of 100 based on stability, healthcare, culture, environment, education, and infrastructure. I believe that a key reason for our success is in the recent redevelopment of Swanston Street, Melbourne’s busiest pedestrian and public transport route; its 'civic spine'. The redevelopment is part of an ongoing effort to make Melbourne’s streets more “accessible, safe, and enjoyable”, pointing towards a future of "social" rather than "mass" transit. Sidewalks were redesigned, widened, and repaved to incorporate high-luminance tactile tracts. Audio bollards were installed at tram stops, announcing the arrival of trams. Street lighting was improved; safety railings, and separated bikeways were created. Missing links in the pedestrian network were repaired, creating a seamless journey around the city. Traffic calming measures were implemented: cars were removed from the street and replaced with sidewalks that were raised to be level with tram platforms. Now, trams have became a continuation of the street. As a tram glides to a stop outside the State Library, a friendly man wearing a reflective orange vest waits by the door to direct passengers and to offer his assistance. In The Living City, Robert Gratz said that “preserving the urban fabric, weaving together the treasured old and the needed new, not being afraid to think small – that is what genuine revitalisation is all about.” And this is where the Swanston redevelopment succeeds. By starting small, it transformed a street that was previously too crowded, too chaotic, and too unsafe, into a vibrant, inclusive, and accessible public space.

Follow me as we venture down Swanston Street. Look around; a street is a special place in our city. It is a place where people would like to be; to walk, to talk, to meet, to play, and even just to sit on the grass and watch people passing by. Here, people of all abilities come to socialise. An array of shops, services like toilets, telephones, drinking fountains, community places like libraries, train stations, theatres and public squares are all within everyone's easy reach. A couple of times a year, Swanston transforms itself into a ceremonial and parade route with a view of the Shrine of Remembrance down the open vista. Its unique visual and spatial qualities, makes it a significant and attractive route for the Moomba Parade, Anzac Day March, Melbourne Cup Parade, Grand Finale Parade, and the Christmas Parade. These events attract large crowds from all backgrounds, eager to participate in the festivities. The raised platforms on the sidewalks not only allow people to come together and mingle, they seem to enhance the experience for spectators, separating and keep them out of harms way, and elevating the viewers above the procession. In the new design, the absence of permanent shelters or barriers ensures views are not obstructed.

Our Central Business District, which takes the shape of a rectangular grid, lends itself to particular accessibility benefits. Buildings inhabit little square pockets between parallel streets, which make them relatively straightforward to navigate. We developed as a port town in the early 19th Century, so the speed of transportation and the exchange of attractive commodities for trading, was a high priority for city planners. Even in the early days, our street's accessibility would have been considered relatively "good", seeing as how most residents made their journeys on foot. Subsequently, new modes of travel in the form of horse-carriages, railways, tramlines, motorisation, and suburban sprawl further added to the complexities of physical, environmental, and psychological barriers to transport: challenges that transport-disadvantaged people face today. There is no doubt that the urban planning system put in place in Melbourne in the 19th Century, has generated the urban plan which creates the unique travel needs for our residents.

What makes an accessible street?

Historically, many cities have developed along the banks of rivers to take advantage of quick transport links between places. In geographical terms, a river is an "accessibility resource": "a naturally occurring landscape feature that facilitates interaction between places." Similarly, the street is our present day man-made accessibility resource. Not only is it a transport link, it also facilitates the interaction between people from different places. Luckily, we can control the form of the streetscape, and we can determine how the street adds value to our transport system. In a local publication, Creating Accessible Journeys, an accessible transport system is defined as "one that provides good access: it successfully transports people to the places they need to go". I'd like to add to this definition; that the accessible streetscape should also act as a "thick edge:" (Borden, 2006) a multiple layered space where the human body is engaged in a holistic way (via all its senses). In this way, space can "assume a more social character" (Borden, 2006): people with a diverse range of abilities can access, and experience full engagement with their surroundings.

In 2002, the Australia Government enacted the Disability Standards for Accessible Public Transport (DSAPT), under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (DDA). This required various aspects of public transport services to comply with standards set by DSAPT. For Melbourne's City Design Division, research on "compliance" and providing "good access" brought their attention to the design of tram platforms in Orléans, France. Here, according to Director of City Design Rob Adams, the team found an interesting project which demonstrated the possibilities of good accessibility rather than just achieving a compliance target.

The Orléans tram route was similar to Melbourne's because it passed through a wide range of land use types: historic districts, leafy suburbs, commercial and industrial areas. Over the long stretch of line, the great variety of sites presented a unique urban challenge. Local authorities were tasked with developing a design solution which was both connective and cohesive. The challenge was to find layouts and technical installations suitable for each land-use type, while achieving a uniform look and feel to the system. The premise behind their solution was that the design of the tram platform, and reordering the hierarchy of street users, held the key to providing better access. A post-occupancy analysis of the accessibility improvements revealed that the development of Orléans' tram line activated the city. It resulted in six new park-and-ride sites; the bus network completely redesigned; the coach station transformed into a multi-modal hub. As a result, the redevelopment led to the regeneration of several urban locations, notably the Commune de Paris at Fleury-les-Aubrais, Charles de Gaulle Square, and Croix Saint-Marceau Square.

Encouraged by this, the Melbourne design team decided the right thing to do was to rethink how trams and people interact at the street edge. The existing tram tracks were lowered and the pavement was extended all the way to the platform edge to create a flush seamless surface. The bicycle track between the existing kerb and the platform edge was constructed in different paving materials to denote its status as a "road". The footpath was tiled with contrasting stripes in white granite and bluestone, improving the civic feel of the street. In addition, the rearrangement of street furniture improved visibility across and down the Swanston Street vista. Non-compliant trams are being phased out in favour of trams with flat, low floors. Previously, solitary tram stops disrupted the streetscape. Now, the new design allows tram passengers to board a tram anywhere along the full length of the footpath, thereby speeding up waiting times for trams and reducing congestion.

This new streetscape both invites and evokes the senses. In Melbourne, the redesign of the tram platform is complemented by a new public art program, while the smell from Eucalyptus trees and new floral plantings permeate the air. As a result, cafes and retail shops are now beginning to upgrade themselves in order to complement the street’s new design, fully engaging the experience of the public.

However, Melbourne's new tram stops come with a heavy price tag. The tram stop at the State Library forecourt alone cost $7 million, and the other tram stops running the length of Swanston Street cost another $6.1 million each. A further $300,000 was spent on the overall design. At this cost, it is unlikely that such money, care and provision will also be provided outside the city. In 2012, the challenges of designing a successful transport-city became obvious when two trams struck a blind woman and her guide dog on separate occasions outside Melbourne's City. In the first incident, her dog became concussed after being struck. In the second incident, the tram swiped past, dislocating her shoulder. She lost control of the arm she used to hold on to her guide dog, which left her immobilized. On both occasions the tram drivers were unaware of the incidents. It is becoming increasingly clear that instead of focusing the redevelopment in the city centre, urgent attention must now be paid to continue the redevelopment efforts into the streets of inner and outer suburbs.

People usually underestimate the scale of disability in the Australian community. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports that currently 20% of Australians report a disability of some kind. This is considerably higher than that reported in Europe (10%) and the UK (14.2%) (Allen & Currie, 2007). A major result of these higher numbers of disability is reduced trip-making compared to others in society: people with disabilities make a third of the number of trips (8 per week) as the rest of the community (24 per week) (Allen & Currie, 2007). It is a pressing issue in Melbourne, where an ageing population, and an increasing incidence of blindness through diseases such as diabetes means that any failure to improve the accessibility of the city’s spaces risks isolating a growing section of society.

A local study from the Brotherhood of St Laurence, explores the social exclusion of the elderly with regards to public transport. Most participants commented on the convenient local public transport options -- that trams were within comfortable walking distance. But for those participants experiencing increasing frailty and health problems however, public transport was not always accessible. Two participants, Doris and James, felt they had no option but to use taxis —unless friends or volunteers offered to drive them. Even then, taxis were too expensive given their small incomes. This limited them doing the things they would have liked. Some participants chose not to use taxis because of unpleasant previous experiences. Two participants, Shirley and George, said public transport would not be accessible to them if they were unwell. Shirley has to walk "about five or eight minutes" to the tram stop and if unwell "I wouldn’t be able to get down to it, would I?" (Angley & Waterhouse, 2005)

Taking the tram could pose difficulties as well. Some participants felt they couldn't claim a seat from other passengers. According to Shirley, "that’s the generation as it is now, you know … If you say anything on the tram—‘Could you stand up?’—they’re likely to bang you one on the face … So you just grin and bear it, but it comes back again to transport, that if you’re sick, you know, what’s your answer?" (Angley & Waterhouse, 2005)

Often, people who are socially disadvantaged also have limited access to transport options, and hence have difficulty participating in activities. This is a vicious cycle: people are not able to get to places such as jobs, health services or other services and therefore, fully participate in society and staying socially disadvantaged. Therefore it is crucial to address transport disadvantage in order to enable people to fully participate in society.

Still, the future of accessibility here is looking hopeful. One of the key recommendations in a report by Annette Kroen at Melbourne's Department of Transport, suggests we take a cue from Toronto's Department of Transport and create an annual Accessibility Plan. In doing so, it would be a tangible way to track advances regarding accessibility for people with disabilities. It would also help to set clear targets that need to be achieved in the following year. Annette suggests to name this document the "Disabled Accessibility Plan", to clarify that it concentrated on issues for people with disabilities and not on a broader definition of accessibility.

In the meantime, we must acknowledge that the Swanston Street redevelopment is big step forward. Our trip down Swanston Street helps us imagine what is possible for Melbourne's other streets. After our long walk, we sit under the cool shade of a tree. At dusk there emerges a certain stillness about the street. The rooftops of buildings seem more docile. Even the spire of St Paul's Cathedral sheds its imposing air, shrinks back into the trees, and diminishes in stature. Sometimes, when we create an Enabling City, we aren't afraid to come out, and be ourselves.

References:

Allen, J., & Currie, G. (2007). Australians with Disabilities: Transport Disadvantage and Disability. In: Currie, G., Stanley, J, and Stanley, J., (eds.) No Way to Go: Transport and Social Disadvantage in Australian Communities. Clayton: Monash University ePress.

Borden, I. (2006). Thick Edge: Architectural Boundaries and Spatial Flows. In: Taylor, M. and Preston, J., (eds.) Intimus: Interior Design Theory Reader. Chichester: Wiley.

Kroen, A. (2011). Addressing Transport Disadvantage of Older, Disabled and Low Income Population Groups. Melbourne: AITPM 2011 National Conference.

Morgan, T. (1992). Strategies to overcome transport disadvantage. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Oliver, M. (1983). Social work with disabled people. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Angley, P., & Waterhouse, C. (2005). Social Exclusion Among Older People: A preliminary study from inner-city Melbourne. Melbourne: Brotherhood of St Laurence.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |