[ID:4857] Growing Through TimeUnited States In the realm of the natural sciences, the scientist proposes a question to nature by conducting an experiment. This is what occurred one June afternoon when the earth became gray and Benjamin Franklin flew his kite into a thunderstorm. He dared to ask a question with the potential of transcending all situations: are lightning and electricity of the same blood? The man of science only participated in this act of discovery—nature, was the one that gifted the answer.

Diving into the multitudinous spheres of scientific exploration, the personal equation, a tendency toward including personal bias in the act of judgment examining fact or opinion that affects variations of interpretation, is refused entry. In a similar realm, contemplating in a circular chamber of ideas, sits the architect. A place where the matter of design is in service to ideas and to people. Thoughtful creation beckons us to recede from biased cravings of personal influence in order to create environments looking toward a humanly desirable direction. To endeavor on such a task, we must become the ones of today to ask the questions that have the potential of transcending all situations.

Recently, such a question has risen from the waters: how do we move forward with design for the aging? A question, with an answer that can only be gifted by the “nature” of the people.

To begin, who are these “aging” that we are attempting to design more fluently for? In the United States, a person is officially considered at the top of the hill at the age of 40. Furthermore, in the article “To Design for the Elderly, Don’t Look to the Past” by Mathew Usher, a presented study predicts that by 2050 the amount of people inhabiting the world of 65 years and older will have increased to 16.7%. Therefore, when referencing the “aged” or “aging” population, it is directed towards those of 40 years and older. Whereas, when speaking of “senior citizens” or the “elderly”, it is directed toward those of 65 years and older.

Due to the naturally occurring processes of life, certain changes gradually transpire and slowly gain a stronger and more firm grip upon our minds and bodies. As a result, there comes a day when society labels groupings of people as “aged” or “elderly” due to their outward appearances and a supposed rapidity of decline in their capabilities. However, these labels only place limitations on these people based upon subjective, external ideas. Ultimately, these are simply people who are all experiencing similar changes simultaneously. People—who only wish to do their best to continue to live the life they desire. However, within this desire, these people must come to an objective truth intrinsically. They must reflect and understand their own limitations in order to hopefully promote a continuation of good health. Outsiders to the essence of these changes must demonstrate empathy and try to comprehend the feelings of those experiencing something they have yet to encounter. For sooner rather than later, these changes will affect us all.

Collectively, we must evaluate the social and physical adjustments that our aging population is growing through to, in turn, promote new ideologies and create new architectural environments that nurture the nature of our aging communities. We must gaze into the mirror of the past, which is inherently responsible for our present, to discover the successes and failures of those who came before to build a better life for those who come next.

The nature of the people is something rather hard to pin-point. Desired nature differs from the inherent nature of the race. However, one thing that shall remain true till the end of time is the cycle of aging. Looking toward our aging population, there remains some unrelenting desires that have stayed with them since their youth, in conjunction with some newly developed needs owing to their current position in life.

The way of contemporary society is to disregard the aging. This creates a deep rift between the different groupings of people in a community. Therefore, the elderly have a tendency to cluster together because they have no appetite to be among younger generations that lack respect and appreciation. This rift between younger and older damages them individually, as well as, collectively. The opportunity to learn from one another and bond over the ways of life is nonexistent. In turn, this segregation crafts a similar rift inside the hearts and minds of the aging individuals. Without the circumstances in which they may share their past, the idea of their youth loses all meaning. Of course, people vary in personality and needs. However, what determines the reaction of architecture on behalf of the aging is their potential for living closely to their youth and their needed level of care. The more able-bodied they are, the more independent they are able to remain. This ability lessens the need to be among older peers, as well as, lessens the need to be in close relation to special medical services. Yet, those that are in need of more consistent and dependable care systems find themselves with extremely limited housing experiential opportunities. Often, even those who only need relative assistance with simple, daily tasks find themselves placed within these debilitating care facilities. This comes at a large expense to the individuals, their families, and the community. This act negatively affects their psychological states and turns them into beings who are fragile and incapable because that is the way they are treated [I]. Human nature, in general, has a desire for connection, sociable activities, and independence. Therefore, by understanding the audience for which we are designing, we will be able to make environments that allow for these qualities to ensue freely.

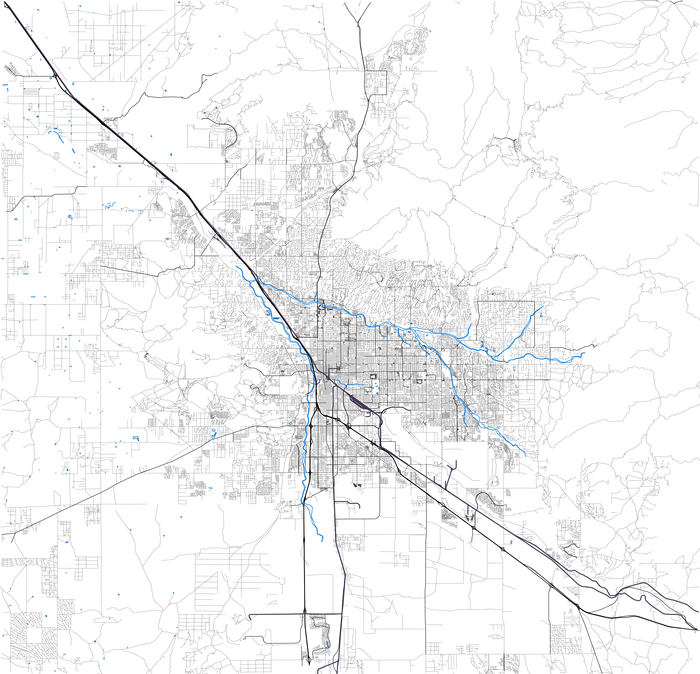

To continue, Tucson originally began to develop its first forms of construction parallel to the Santa Cruz River and the main railroad tracks of the time. The beginning of organic growth; slowly starting to mature within the womb of a Sonoran Desert valley. Eventually, this natural development fell victim to urban sprawl, the expeditious expansion of the topographical range of a city or town, “Seeing demands a certain activity on the part of the spectator. It is not enough passively to let a picture form itself . . .” [II]. Seeing Tucson, the reinterpreted picture expresses flaws within the experiential qualities of the city’s disconnected web of structures that excretes difficult living conditions for the aging population.

Stitched together by linear spatial divisions, the city creates a separation of the land through roads extending in the primary cardinal directions to form a basic, subdivided grid. A result of multiple phases of urban sprawl. Due to Tucson’s continuing expansion, the city has developed a lack of balance between the functionality of its architecture in relation to the region. Spreading further outward, the relationship of solids and voids has become one of low density. Letting in the materialization of detached neighborhoods by building a “wall” between the community and the individual through architecture. These spaces amplify feelings of isolation, solidarity, and loneliness. Also, this separation of architectural communities on the grounds of unevolved thoughts of urban planning has created a reliance upon the automobile for transportation. This invites difficulties for those who do not have access to a private vehicle. Overall, the disengagement created by the city planners because of the implemented types of zoning separates the architecture from the city and sequentially separates the architecture from the people. Therefore, the primary concern in the design of Tucson is in regards to accessibility, movement, and the current conditions of assisted living.

Accessibility—is our opportunity to discover what lies on the other side. It is freeing of restraints while passing on the key to new experience through . . .

Movement—the telling of life. It is the circulation of our energy and the procession of our flowing through social and environmental time and space. A forced alteration of these atmospheric qualities occurs for the aging due to the . . .

Current conditions of assisted living—placing a loved one in a home that is not a home. A place inducing feelings of being left behind to face a world alone who only considers you as a liability.

During Tucson’s process of development, senior citizen care facilities were attached to the city by old modalities of thought. They represent a separated world. An archipelago in the density of this particular urban environment. Placing the elderly within these “homes” reveals the sad state of modern culture. However, a more vital, purposeful aspect of Tucson’s culture is the preservation of historic structures and neighborhoods. These historic pieces of architecture are humbly evocative. The old style oozes with charm and beauty. A sensation that has become an important feeling of the city. Even so, due to their construction of a previous age, at times, access becomes a threat and movement becomes a potential hazard. Old pieces of material protruding in unfriendly manners and circulation systems built around the use of stairs requires an increased visual attention and an increased physical ableness for the aging to traverse the architectural landscape. Preserving the buildings, preserves the culture. Architectural practices must begin to shift their ideas relating to elderly care facilities to the modern frequency. Yet, in the spirit of maintaining the good aspects of Tucson’s culture, local architects have already begun to implement the idea of renovation. Not an attempt to destroy the past that has dictated the current architectural feel of the city, but an attempt to adjust the contemporary idea of space to create a more inclusive day.

The Coronado Hotel has recently reopened after its engagement with the ongoing process of urban renewal in Tucson. The structure was originally built in 1928. In 1992, the building’s program was altered to an assisted living facility. Most recently, it has been transformed into an apartment complex. The renovation dealt with refurbishing the exterior while entirely reworking the interior to produce 30 micro-housing units. This maintains the cultural aspect of the surrounding context while offering newly designed layouts simple in space and functionality. The adjusted interior incorporates universal design and allows for leisurely circulation. The units are an excellent option for those who do not need to occupy an expansive amount of space while still indoctrinating the resident with a feeling of peace and of home. Natural light pours into the black and white interior with a view of the adjacent city context.

Due to the structure’s location, availability and access to the streetcar line are in close proximity. However, there are a multitude of shops and other sociable architectural experiences within walking distance. Further, the apartments are built on top of a local cafe. Therefore, one must not even leave the building in order to discover an open social environment where all people are welcome to converse or enjoy the distant company of others. Overall, the interior incorporates amenities of modern design, with a touch of historic culture, in a field of opportunity to be a part of the urban community.

The Murphy-Wilmot Library originally designed in 1964 by Nicholas Sakellar, later to be completed in 1965, was the third library to be constructed in Tucson. Beautiful mid-century architecture that exhibits the architect’s sensitivity to the arid environment of this particular desert region. The building nestles itself within the land. The entirety of the building is formed from sculptural horizontal planes and smooth materials that welcome a universal accessibility. The spacious interior allows for unobtrusive movement with many places of comfort to rest. Windows provide views outward to the Catalina Mountains and let in abundant pools of ambient light. The whole of the structure is composed in a single story with green courtyards only a footstep away.

Since its initial materialization, Nicholas Sakellar’s son, Dino, has completed multiple expansion and renovation projects on the library. Prior to initiating the design concepts, an emphasis was placed on reaching out to the surrounding neighborhoods to ensure the new additions would be inclusive of the users’ needs.

The additions maintained the elements of design crafted into the original architecture. More study rooms, meeting rooms, and seating areas were created. The improved entrance is both welcoming and warm. Leading those who enter either to the bookshelves or to the public food area where people may sip their coffee while enjoying the company of others, as well as, the company of new knowledge. A bus stop is located less than a block away from the entrance. Also, the library is within walking distance to the surrounding neighborhoods and the adjacent school. All embracing, this library is a place for those of all ages to gather, interact, and enjoy stimulation of the intellect. A refuge for anyone to feel a part of a collective community even when only wishing to enjoy a book in silence.

To recreate the patterns of the city, we must slowly begin to build momentum of thought and design demonstration for the overall growth of interaction between the people and their architecture. For the aging and the elderly, we must make adjustments for them to remain within their familiar neighborhoods to best maintain their sense of home. We must create new environments, as well as refresh old ones, for the young and old to be in relation to one another. We must allow those who wish to continue living independently to do so without revoking their feeling of community and accordingly, invoking the feeling of isolation. We must make assisted living accessible without requiring those who need it to leave their homes. Finally, for those who desire or need to be around their peers in a care facility, we must recreate the environment of inhabitation for this program. Creating a place based upon an organism where the people have freedom and feel safe to move and interact at their will. A place of social invitation where visitors feel comfortable and the residents do not feel trapped in isolation. A true home, where they may contain feelings of comfort and of a continued purpose in life.

Ultimately, when designing for the aging, we are designing for all. Aging begins at the first moment of our life. Therefore, we must endeavor to create architecture that embodies beauty, gentleness, and forgiveness. Making worlds within the world that are places for people to grow through life. In order to do so, we must look to the past. We must study previous ideas, philosophies, explorations, and constructions in order to understand what has previously been devised in dream and in material to create something freshly revolutionary. For without the past, there can be no instrument of progress for the future.

[I] Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Angel, S., Fiksdahl-King, I., Jacobson, M., & Silverstein, M. (1977). OLD PEOPLE EVERYWHERE**. In A Pattern Language: Towns-Buildings-Construction (pp. 215–220). New York Oxford University Press.

[II] Rasmussen, S. E., & Wendt, E. M. (1962). Solids and Cavities in Architecture. In Experiencing Architecture (p. 35). M.I.T. Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |