[ID:3963] Concrete jungle to dream homesIndia Introduction

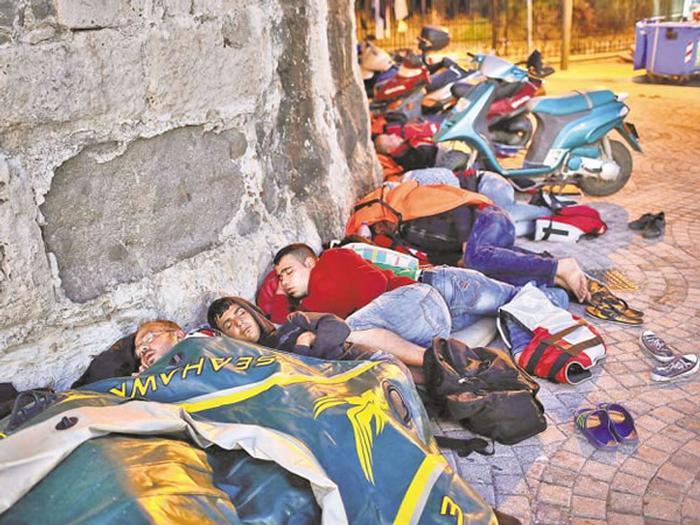

As winters approach in Delhi one can often see people snuggling into their blankets on a cold night ready to sleep on pavements, under pledged of shops and homes, in market corridors, at bus stands or railway stations,in market corridors, outside places of worship whichever gives them comfort as close as to a home.

The bitter winter cold often proves to be a messenger of death. Many die unmourned on the streets and the life they have lived is a continuous struggle against sickness, loneliness and hunger. Even more people die on Delhi’s streets in the summer heat and monsoons than those who are defeated by Delhi’s harsh winters.

Homeless people even though visible to the makers of policy live in our cities virtually as non citizens. The legitimate citizens of the city who are deemed to deserve both protection and services from the State are those who live in homes and settled orderly colonies. There is an unstated de facto hierarchy, in which the homeless people are at the bottom.

The relationship between them and the state is one of extreme mutual acrimony and distrust. State authorities are distrustful of homeless people as being parasitical, lazy, unhygienic, illegal and largely criminal. Homeless people return the compliment by regarding the government as implacably uncaring, hostile, corrupt and neglectful. To them the state owes nothing except to drive them away from city in which they have no have rights to whatsoever.

Living rough

In a study, S. Murlidhar (then a Supreme Court lawyer and civil rights activist, now a judge of the Delhi High Court) observed:

Criminalizing the homeless is a serious problem; wandering people of a wide variety can be defined as beggars and powers are given to the police to deal with such persons. Squatting on the pavement is nuisance under the Municipal laws. Creation of nuisance can be penalized.

Large numbers of homeless people daily face harassment and police brutality. They are routinely rounded up by the police and put into jail or beggar’s homes where they languish for long periods. As they lack access to legal aid and have poor literacy they end up staying there too long.

In the case of homeless people, two documents are widely considered for the proof of citizenship – the voter’s card and the ration card which is mostly not available to the majority. The reason often cited by authorities is that they lack a permanent address. Also majority of them lack birth certificates. Homeless people are therefore denied not only citizenship but also participation in decision making and opportunities for secure tenure and housing rights, credit, education, health care, water and sanitation and a host of other basic services.

Not having any proof of identification and address means not being able to claim Below Poverty Line (BPL) or and other related food schemes. Only one-fifth of the respondents in the Centre for Equity Studies (CES) study possessed ration cards. The rest either never had issued one or had their card issued before migration. Others had lost them while moving from their native houses to the city. Even if a majority of the homeless are aware of the need for ration cards and voter identification cards, most are rarely able to possess these basic government documents, due to their powerlessness.

Other social assistance programmes such as old age pensions, death insurance and maternity benefits are simply out of the reach of the urban poor. This is either due to their contested citizenship because of lack of permanent address, or due to the lack of political will and administrative rigor by the government in delivering the benefits to the homeless. In Delhi, for example, no aged, homeless, urban poor person was found to have accessed rice under the Annapurna scheme(food scheme). Others have tried a great deal and ended up frustrated when asked for bribes to avail of their rightful entitlements. Most have given up.

Shelters for the urban homeless in the past

Based on the Fundamental Right to Life under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, the recent interventions of Supreme Court of India provide a legal framework for new policy architecture for the urban homeless people of India.

After a series of deaths of homeless persons on Delhi’s streets in the winter of 2009-10, the highest court of our land stepped in to enforce the rights of these most marginalized persons to a life with dignity. The Municipal Corporation of Delhi was directed to draw up a plan to construct 140 permanent shelters for the homeless across Delhi. Further, the Court directed that these shelters must provide basic amenities such as blankets, water and mobile toilets.

Government agencies joined hands and more than doubled the number of shelters in Delhi in the span of two days.

The Tata Institute of Social Studies (TISS) study found that the quality of shelters that existed in Delhi was found to be very poor, with minimal facilities, which did not meet the requirements of the homeless. This was one of the main reasons for the underutilization of the existing shelters. While in some shelters, there were no toilet facilities, even in the rest , the toilets were not clean and there was not enough water. There were no clean beddings in any of the shelters as the contract for beddings had not been finalized by the government. Almost half the centers did not have the facility for adequate and clean drinking water. This pushes them into deeper vulnerability, a vicious cycle of poverty, dispossession and even starvation.

It is important to understand why this programme failed. It was a demand driven programme, based on demand from local city and government, which rarely came because of the invisibility and powerlessness that surrounds homeless persons. The programme was managed by The Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO), which, under the supervision of Ministry of Urban Development, was responsible for appraisal, financing and monitoring of the programme. The Government of India in a sense, did not directly own it.

A possible solution

Many unfinished high rise buildings remain abandoned due to economic crashes or obsolete building systems.This space can be used efficiently by designing dwelling units for the urban homeless. Our architectural education enables us to find an affordable and sustainable way to shelter the homeless. These buildings that are often occupied by squatters can be made to great use by suitably refurbishing it and developing it according to requisite service and space requirements.

This year because of the Covid-19 pandemic it wasn’t possible to talk the community directly so we managed to found out from our research that one of the key reasons why homeless people don’t use shelters and instead choose the option to sleep in the open is because they do not want to go far from where they work because it is inconvenient and they are afraid of their things being stolen.

No matter how many efforts we make it is pointless to locate homeless shelters at the periphery of cities, because homeless persons cannot viably reside in locations distant from where they can find work. Many of them are casual workers and must be present every morning at their required place so that potential employers can hire them. Location is critical for street vendors, domestic workers, rag pickers, rickshaw pullers, construction workers, casual sex workers and persons dependent on begging.

Hence, the location of the housing should be in areas, which are close to their livelihood opportunities/work sites and where there is a concentration of homeless persons. The City Level Empowered Committee (CLEC) should take the decision on locations of shelters. The CLEC may be constituted by a dedicated group, coordinated possibly by a senior official with interest and aptitude, local schools of social work, leading NGOs with direct experience of working with homeless people.

The homeless population is extremely heterogeneous in terms of age group, gender, livelihoods, place of origin and their reasons for living on the streets. It is a group that we can meet only in the evenings or late at night, because what serves after dark as their dwelling becomes with sunrise, pavements, streets, road-dividers and shopping corridors. The homeless are also sometimes of unstable location and may move from day to day to different parts of the city, or even to other cities. Therefore, planners should obtain the latest estimates of the city population, and estimate the population of homeless persons to be one per cent of this figure.

Planning for permanent housing and allied services for the homeless at the national, state and city levels requires coordination with several line ministries and departments, with urban local bodies, as well as with various social work, health and town planning professionals, homeless collectives, unorganized worker unions and various civil society organizations.

Government needs to understand that this will help improve urban rural equality by narrowing down the difference in the standard of living.As a future architect we can make the decision makers understand by explaining that house is more than a roof over the head it performs multiple functions including many social needs of the household.

At the central level, there is a need to authorize the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation (HUPA) and under it the National Urban Livelihoods Mission (NULM), to provide overall leadership to the programme nationally. Technical support could be sought from Housing & Urban Development Corporation Ltd (HUDCO) and where needed, from selected schools of architecture and social work, which are of national reach and reputation. At the state level, the State/Urban Local Body (ULB) would establish the housing and operate them directly or through agencies identified by them.

In case buildings are not directly under the control of the municipal authority of the city, the City Level Empowered Committee (CLEC) will work with various departments to obtain No Objection Certificate (NOC) s. The Committee will also work with the government to release designated funds for refurbishment and construction of the houses, and for running costs.

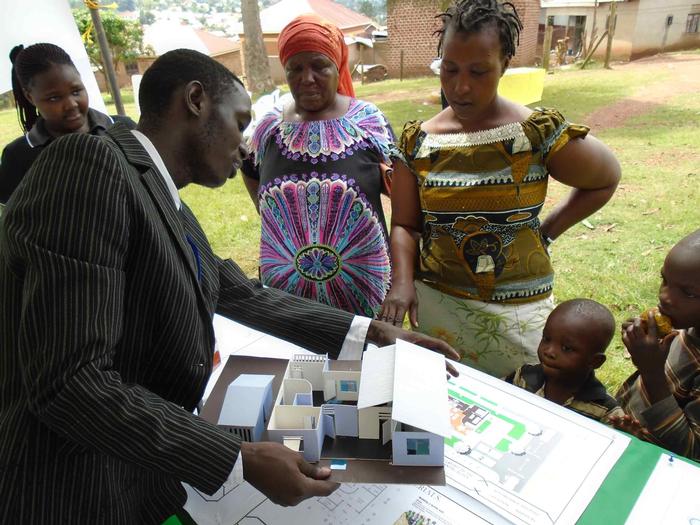

Architects in service to the community

Over years we have seen how typical housing projects have been looked upon as a solution for the homeless, and have failed terribly. We need to change our perception towards the homeless and start including them as a part our society.

As a future architect the most viable solution will be understanding the community. In this scenario each user is different and so should be our approach towards them. Architects need to, observe the users, their behaviors and interact with them to understand their problems and the reasons for their present state.

There should be a suitable mix of houses in a building for men, women and families, and special housing based on the local homeless population profile which can be found out after research by the committee. The following can be the types that should be constructed:-

1. General, these are all weather, day-and-night, permanent shelters. Since the maximum population among the homeless is of men, general shelters would primarily cater to single working men, with special facilities available for special groups within, such as recovery rooms for male persons recovering from grave ailments and spaces for the male aged and disabled.

2. Special, These are also permanent, all weather, day-and-night shelters. At least a third of all shelters in the city should be devoted to homeless people with special needs and build at their location, with design and services catering to their special needs. These will serve homeless populations that fall among the following categories: (a) single women and their dependent minor children, (b) the aged, (c) the infirm, (d) the disabled, (e) the mentally challenged etc. Separate shelters need to be set up. Actual break-up would depend on local particularities, and size of the city and total numbers of shelters.

a) Women housing: Housing for the exclusive use of women in terms of location, design, services and support systems, should be designed to cater to the needs of women and their dependent children. In every Urban Local Body (ULB), no matter how small the populace, at least one such building for women should be there.

b) Family housing: For families living on the streets; family shelters should be provided, with a special design for privacy, with shared common spaces.

c) Other special housing: Taking into account special needs for segments of homeless persons, such as old persons without care, mentally ill, recovering patients and their families etc., special housing may be provided.

For these most vulnerable segments of homeless people such as old persons without care and mentally ill and challenged persons, psychosocial counseling, treatment linkages de-addiction services and health services should included. In addition to the above facilities, the special housing for women and children also need to have certain special provisions. Protection, security and privacy for women must be ensured. Special care needs to be taken to ensure the security of residents of women’s shelters in view of the violence, abuse and exploitation they face on the streets. .

Also when existing abandoned buildings are used, the building must be certified structurally safe for human habitation by a competent technical authority. The certificate should be suitably updated periodically. Permanent shelters should be designed in an environmentally friendly manner, with flexibility in design, to cater to local systems and needs. The homeless shelter structure should be safe and secure with a sense of belonging for the inmates. The architectural design of the shelter home should take into consideration the region’s weather conditions, so that it provides protection against extreme climate. The infrastructure should have sufficient minimum numbers of toilets, sanitation and waste disposal infrastructure, with adequate supply of water, electricity and safe storages spaces like cupboards and lockers. The building should be bright and well ventilated with adequate windows, doors and grills.

Putting ourselves into the souls of others

Unless we start building the discourse of empathy and experience in our homes and institutions, no matter what education we get or give the vision for housing for all will not happen because people would not be sensitive and empathize this idea.

The roles of architects are no longer about brick and mortar any longer, they never were but the roles have been how we shape environment in a way the that the humans who live in it can experience it in their own way and can facilitate what they were supposed to be doing there which mean fulfilling their everyday functions and goals.

Unfortunately, at this point it’s become an understood fact that the homeless are stuck in this cycle, unless an urgent change is made, both at the level of attitude and at the level of development policies and programmes.

Homelessness is not a choice. It is a lack of other choices. Those living in poverty do not experience the privileges you and I do. They have limited choices on where to go to school, to live or work, because lack of income and education holds them back, and lack of access to affordable housing, transportation and job training keeps them trapped.

We would like to conclude by a quote by Sheila McKechnie“People who are homeless are not social inadequates. They are just people without homes.”

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |