[ID:361] Building Street Dreamscapes: The Durga Puja Pandal at KolkataIndia A familiar Kolkata transforms. Neighbourhoods introduce themselves in unforeseen ways. The ‘Durga Puja Pandal’ announces its arrival.

“Come-hither every year!” – people sing in chorus.

In a world where increasing disconnection of people from urban spaces is paralyzing modern urban neighbourhoods, the story of the ‘Community Durga Puja Pandal’ in the city of Kolkata, the Indian metropolis in the state of West Bengal, holds special importance and ought to be narrated. It is an example of an Indian community’s search for identity in the midst of diversity, the search embodied by the very act of building.

‘Durga Puja’ is the annual autumnal celebration of Goddess Durga during September-October over five days and nights. This celebration is characterized by the act of building the community ‘Pandal’ – a temporary shelter or a marquee that houses the idol of the Goddess during the festival. The Pandal skillfully combines craftsmanship, symbolism and various cultural, political and artistic intents. The introduction of this dynamic, yet structured concept of ‘community-building’ into the city not only makes it the fulcrum for a robust and vibrant public life but also connects various cycles of the city and its environment.

OF NEIGHBOURHOODS, DURGA PUJA PANDALS AND THE PUBLIC REALM: The imagery of Kolkata brings forth images such as banks of the river Ganga, greens of Maidan, Howrah Bridge, Victoria Memorial, colonial buildings of Parkstreet, mansions of North Kolkata and narrow congested streets with back-to-back houses, amongst many others.

Though difficult to consider, as people of Kolkata say, much of Kolkata can be understood through ‘Durga Puja Pandals’. Community-Pandal-making is a two-century-old concept of people’s desire to explore their collective right to the city. At the base of the festival structure is the ‘Neighbourhood’. Every neighbourhood builds it’s own Pandal. The neighbourhood’s identity is articulated in the symbolism of the Pandal. The temporary space of the festival provides in the lives of people continuously engaged in their daily fight for survival, a momentary phase for dreaming and imagining. The process is a discovery of thoughts, ideas and community solidarity. As thousands of neighbourhoods engage in building their Pandals, the entire city, gripped in the frenzy of the festival, transforms into a surreal world. When one traverses through Pandals of various neighbourhoods, a distinctive landscape of the city emerges. A landscape, that unravels the dynamics of the various neighbourhoods, the interactions arising within and amongst them, their ethos, dreams and aspirations. Such an insight forms a raw yet deep-rooted understanding of the city.

What is it that makes the act of building the Pandal such an important link to the neighbourhood’s life? The answer to this lies in the Pandal’s underlying function, that of acting as a medium to stage, shape and transform public opinion by stimulating dialogue, debate and confirmation. People of the neighbourhood, irrespective of age, gender, occupation, economic class, caste and religion gather to dream and debate.

“What will our neighbourhood transform into this year? How do we design the Pandal in the limited space available? What experience do we portray to the world through the Pandal? Will it have a theme? How much do our means permit? Do we need external resources? Do we need professional assistance to design the Pandal? Who could we approach for sponsorships?” Closely followed by, “Do you think our Pandal has been aesthetically made this year? What do you have to say about the message that our neighbouring Pandal is trying to convey?”

Some neighbourhoods build Pandals that replicate imagery of traditional temples while some explicitly replicate well-known monuments for the sheer joy of seeing these monuments magically land in their neighbourhood! (Image 1) Some conceive the Pandal either as an artistic installation in space or aim to deliver a message, either tell a story or recreate a way of life. Such Pandals in contemporary times are popularly known as theme-based Pandals.

Increasing number and proximity of neighbourhoods celebrating Durga Puja has led to people visiting various neighbourhoods to witness, experience and speculate about experimentations in Goddess images and Pandals. Comparisons and competition are natural consequences. The concept of competition has raised such a stir that it has been institutionalized. Various corporate bodies distribute awards to Pandals for their aesthetic appeal and quality of craftsmanship. Competition acts as a catalyst for design experimentations.

The focus of design experimentations has shifted from the Goddess image to illumination effects and finally to Pandals. In their earliest forms, Pandals were skeletal-frames of bamboo draped in cloth and tarpaulin but gradually experimentations began. Mid-nineties onwards there began an intense effort to integrate all aspects of the Puja, image of the Goddess, lighting, Pandal and ambience, into a harmonious whole.

The roots of Community Puja in and around Kolkata can be traced to the early twentieth century, when Puja moved from elite households to open streets, patronage of elite families to community sponsorship. This brought the Goddess amongst the masses. Like any other public sphere, it adapted to dominant needs and trends of the times. The contemporary Indian public sphere has gained momentum by factors such as emergence of a nationalist popular domain, the colossal task of nation-building post independence, emergence of the mass media and various consumerist drives. In Kolkata, the Durga Puja Pandal served as the stage where these got projected and shaped. So, while the image of the Goddess took the form of ‘Bharatmata’ (Mother India) as a result of patriotic fervour pre and post Indian independence, the Community Pandal provided the traditional support system of community life and a sense of belonging to thousands of people who migrated into Kolkata as a result of the partition of Bengal.

In the contemporary Pandal, one would be intrigued, even surprised, to witness the paradox in a devotee offering tribute to the Goddess in a temporary street-corner-shrine that replicates a ship or is a comment on the latest political issue gripping the nation or is an installation persuading people to save trees! But this is exactly what the charisma of the Pandal is. It has skillfully interwoven worship with mass celebration. Most interestingly, the physical spaces of the festival are not specialized public spaces but ordinary urban spaces such as streets, common plots, and parks. These spaces assume the character of an extravagant public space only during the festival.

MAKING OF A TEMPORAL FESTIVAL SPACE: MYTH AND MATERIALS: The celebration of Durga Puja is associated with an ancient myth. Mahishasura, the buffalo-demon was granted a boon by Lord Brahma, the father of Creation that he would die only at the hands of woman. When the demon waged a war against the world, no one could harness him. Durga, the Goddess who ends all miseries, following a prolonged battle pierced a trident in his chest. The demon was slain. Victory of good over evil was reinstated. This myth is re-actualized during the festival wherein Pandal-making is looked at as the sacred act of re-construction of the mythical world.

What sets the festival time of Durga Puja and the space of the Pandals apart from ordinary course of life is the intense theatricality. The city becomes a stage for multitudes of enactments spurred by Pandal-making. The theatricality of the whole process is set within a mythical frame of reference that lifts it from the realm of ordinary life, endows it with an aura of enlarged importance and embeds it in memory. On the last day of the festival, the Goddess idol is immersed into flowing water. The festival concludes, the Pandal is dismantled and the space reverts to routine life. The cyclic sense of time of the festival keeps traditions alive in memory, through the annual rituals of constructing, debating, participating and viewing.

The ritual of construction of Pandals has nurtured a range of craftsmen enriching the crafting tradition of the region. The festival has become the means of livelihood for innumerable local craftsmen. For example, an entire neighbourhood, ‘Kumartuli’ has nurtured craftsmen who are knowledge-bearers of the regional sculpting method of straw-bamboo armatures and clay, characteristically used for sculpting Durga idols.

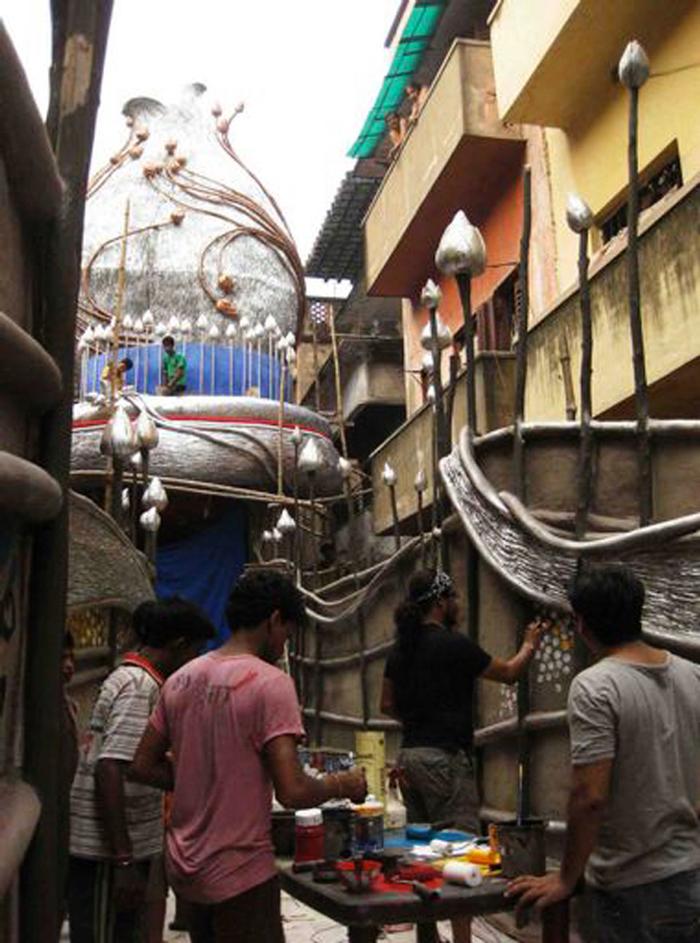

Pandal-making prescribes an extremely tactile method of building wherein there is an intimate connection between materials and the craftsman’s method of working. The specific manners of working with bamboo or mud in Pandals derive from techniques and craftsmanship evolved in this region over centuries. As soil in this region is suitable for bamboo to grow in abundance and for wattle and daub construction, most houses in villages of Bengal are built in this technique. Other materials such as straw, jute, rice-husk, paper and timber used in Pandals are also sourced locally. It is the most natural and ecological use of materials in construction. Temporality of the festival ensures that most materials used can easily be dismantled and reused. A basic bamboo-framework attains form with elaborately crafted elements and finishes. Steel is also used, though sparingly, in some large Pandals to make a basic framework. In recent times, some Pandals also make use of disposed or waste products for construction. (Image 2) Though rooted in tradition, the craftsmen constantly engage in innovative ways to combine regional craft with new tools and technology.

The experience of this temporary yet intricately crafted space of the Pandal and the process leading up to it is a dramatic sensory experience. The best way to evoke such an experience is to recreate the imagery of the neighbourhood whose act of Pandal-making I have observed the closest.

A DREAMSCAPE: An overcrowded street with people, taxis and rickshaws in hustled transit leads to a twenty-feet lane. Back-to-back well-built and rusted-tin-roofed houses characterize the lane. Sky for inmates is the three-by-four-feet windows, through which they chat across streets. Signboards in the lane and paint on compound walls have partially washed out. People are continuously engaged in their daily fight for survival. This is a neighbourhood at Hatibagan, a locality in North Kolkata.

In the fast-paced life of the neighbourhood, there comes a pause, a momentary phase for imagining what the neighbourhood could be. Two months prior to Durga Puja, as the neighbourhood prepares to build its Pandal, the atmosphere reverberates with energy, discussions and joyful anticipation of the unseen world that it is about to transform into.

Bamboo, timber-posts, clay, plaster and hay get collected at the street corner. Sanatan Dinda, an artist with his team of craftsmen, in conversation with people, sets out to design and build the Pandal. The streetscape transforms into his studio, rejuvenated with neighbourhood children kneading clay, sounds of tools and discussions of curious passers-by. Tools mould materials; dreams become reality; the Pandal emerges gradually. (Image 3, 4)

The festival finally arrives. The neighbourhood transforms beyond recognition. Time and history indiscriminately collapse and an entirely new space-time is born. The Pandal is now in public domain, open to being experienced, discussed and interpreted. It is no longer a single viewpoint or experience but the merging of collective experiences of people and the sensations that it evokes.

A towering form at the far end of the Pandal, magnificently rising from earths crust into sky, magnetically draws the viewers towards it. As one moves in relation to it, one crosses the threshold of a large symbolic gateway, underneath a trellis of creeper-like sculptural forms and enters sacred precinct. An enclosure of intricately crafted, undulating mud-bamboo walls on either sides of a ramp holds the sacred space. The dramatic journey of ascent conditions the mind to a heightened state of rapture. One’s roles are in constant reversal, from a viewer to a performer and back and forth. The gradual discovery of materials, colours, textures and shadows of moving bodies of people in relation to shadows of walls and soaring bamboo-posts, responds to ones child-like instinct of play. Every detail, curvature and texture suggests the specific dialogues of craftsmen with the materials. The play of light, shadow and reverberating ritual-sounds against textured surfaces progressively reveal the hidden experiences of the Pandal.

One reaches the towering form only to discover that it is the threshold to the deepest layers within the Pandal. As ones heart pounds in anticipation of what might be beyond, one enters a delicately crafted space of a massive volume. The intimate scale of the sanctum in Hindu temples has been altered into a massive scale. It has been opened up for the masses, not individual but community worship. Beyond all this is the image of Mahishasuramardini (the demon-slaying-warrior-goddess). Momentarily, for the devotee, world evaporates and an intimate connection with the Goddess is established. As the demon is slain, life regenerates. The world gradually materializes and one begins to grasp the details of the space. The unified experience of the mystical ambience, presence of the community and regional crafts presented in an unforeseen manner lifts the devotee to an altogether different plane of elation and fulfillment. The Pandal undeniably is an evocative artistic expression in space.

Finally as one is compressed out into the world of the neighbourhood, one returns to the warmth of the community. The entire neighbourhood is on the street, celebrating. The overwhelming presence of people of the city in their Pandal is an encouragement for their effort. Their Pandal is their pride. In earth, bamboo, plaster and hay, the Pandal is a symbol of their inimitable spirit. The festival ends. The street dreamscape reverts to the neighbourhood of everyday-life. What remains is people’s renewed zest for life ahead. Next festival season, imaginations are new and the same street transforms into a completely different dreamscape.

A fragile-structure generating such a robust public space is fascinating. This is not an exceptional pictorial landscape of the neighbourhood at Hatibagan but that of thousands of neighbourhoods of Kolkata.

DREAM VERSUS REALITY: The entire act of Pandal-making might be a momentary phase of the city when it dares to dream but is it really a dream or is it a reality for Kolkata to thrive?

In contemporary times as we strive to make "sustainable environments", the stance adopted by the Pandal in its approach to a sustainable social system and design is not only bold but also a novel way to keep tradition alive and popular. In social systems, unlike in the use of natural resources, sustainability cannot be defined in terms of equilibrium and permanence. For a social system to thrive, it is extremely important that it is not inert. It has to be inclusive, open to interaction and exchange of ideas. The special importance of “dissent, debate, and dialogue” recognized in the act of Pandal-making makes it an act of unique public significance. Its essence of continually being appropriated is the most important lesson to be learnt in contemporary times when we are constantly trying to make our built environments rigid and resistant to change. The Community Durga Puja Pandal truly is a testimony, in an earthy manner of expression, of what Richard Sennet insists,

“Public Realm is a process, not an end product.”

Works Cited: 1. Banerjee, Sudeshna. Durga Puja, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. New Delhi: Rupa and Co. 2004. 2. Lannoy, Richard. The Speaking Tree: A study of Indian culture and society. Kuala Lumpur, London: Oxford University Press. 1971. 3. Sennett, Richard. The Public Realm. Web. 10 January 2012.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |