[ID:3185] Built to Sustain: A Reconnaissance of the Two Faces of HimalayasIndia Having spent our childhood in the lap of the mighty Himalayas, living in extreme climatic conditions and tackling natural calamities have been embodied in our lifestyle. However, in the recent times, unplanned urbanization has led to a significant increase in the frequency and ferocity of these disasters, thereby conveying that the real crisis isn’t climate change but the anthropocentric desires of man, being achieved at a much greater cost. As the concepts of Sustainability and Climate Resilience gain support around the globe, architects need to step up and in doing so, numerous examples from the past and present exist around them that can stimulate innovative ideas.

This essay talks through the two buildings: the Kedarnath Temple and the Druk White Lotus School, the former being a Traditional Temple whereas the latter a state-of-the-art school. Located in similar climatic regions at identical altitudes amidst the Indian Himalayas, the point of difference is that Kedarnath is located on the windward side whereas Druk White lies in a contrasting rain shadow region, thus displaying distinct techniques to achieve resilience in their respective contexts.

The Kedarnath Temple is an ancient Hindu shrine, dedicated to Lord Shiva, located in a remote corner of the Garhwal Himalayas. Situated at an altitude of 12,000 feet, the view on offer in the Kedarnath valley is simply breathtaking: green depths of coniferous forests, a brown spread of massive rock cliffs and a majestic chain of silvered peaks rising up to 20,000 feet above sea level. River Mandakini, literally translating to 'the calm one’, flows green, deep and silent, down the valley amidst golden grasslands. About 500 feet south-east of the river, the Kedarnath Temple stands in all its glory, like a timeless drop on this ever-changing canvas of the Mandakini Valley.

The temple holds great significance amongst the Hindus and each year millions of devotees undertake the arduous journey to Kedarnath to seek His blessings. This temple was built in the 7th century AD by Adi Shankaracharya, a legendary Hindu reformer and contains a ‘mandapa’ (pillared hall) and a ‘garbhagriha’ (sanctum). Interestingly, the verses on the temple walls dating back to 650 CE, sing paeans to the panoramic landscape without a word about snow, ice or glaciers.

This region of the Himalayas has remained notorious since centuries for extreme climatic shifts due to its complex geomorphological setting: young-fold mountains which are still rising due to tectonic movements, sudden glacial formation and disintegration, nascent glacier-fed rivulets and ephemeral lakes. Recently, archaeologists and scientists of the region discovered lichens growing on the loops of moraines in the Mandakini Valley, suggesting that the Kedarnath temple had remained completely submerged under a colossal mass of snow for 400 years, from the middle of the 14th century till 1748 CE. Even the inner walls of the temple had scratches and striations, marked by the abrasive glacial movement, further verifying the snow cover. In spite of all these climatic vagaries, the temple outlasted this ‘Mini-Ice Age’, unscathed and victorious.

Once the glaciers had receded and the valley became accessible, pilgrimage to the temple resumed. However, the influx of a large number of pilgrims led to continuous construction of more and more structures in the eco-sensitive region. As kids, when we had visited Kedarnath way back in 2012, some visuals got stuck in our memory: a maze of hotels and lodges that had mushroomed all over, congested and crowded market streets and the beautiful visuals of the temple complex with its majestic backdrop being hindered by this unplanned clutter. Even more alarming was the fact that the time-tested traditional construction techniques and locally available building materials had been replaced by RCC framed structures, in the pursuit of modernization. In short, a disaster was waiting to happen and it eventually struck and shook the world in June 2013.

Mr. Nilesh Verma had been stuck in Kedarnath with his wife and daughter as continuous downpour in the valley had held them and thousands of other pilgrims hostages within their hotel rooms. “The usually calm Mandakini seemed outraged and it had changed its course, converting the Kedarnath settlement into an island.”, he exclaims. On the morning of 16 June, when the rainfall had subsided, Mr. Verma decided to visit the temple to receive updates about the situation while his family stayed back in the hotel. “Suddenly, the recital of the 'morning aarti’ (prayer) at the temple was cut short by a deafening thud originating from the North and in no time, a huge wave of water carrying huge debris struck Kedarnath and completely annihilated the town.”

On spotting the killer wave, Mr. Verma rushed and took refuge within the temple premises along with hundreds of others and waited there until the flood water had receded. However, his heart went cold on witnessing the spectacle outside. “The entire settlement had been erased out of sight, including the very hotel where my wife and daughter had been awaiting my return.”, he laments, wiping away his tears. “Thousands of people were consumed either by water or by the treacherous hills where they had escaped to, braving extreme cold and hunger.” Only an inspired effort by the Indian Armed forces, the largest rescue operation till date, could save thousands of lives, including that of Mr. Verma’s, as survivors of the disaster were airlifted to safer locations.

It was during our recent visit to Kedarnath, we met Mr. Verma, a scientist by profession, who has been studying climatic changes in the Mandakini valley ever since that tragic event. He explained the cause of the ‘Himalayan Tsunami’ to be the sudden breaching of the Chorabari Lake as fast-moving water from the lake gained momentum during its descent down the steep slopes, picking up debris that ultimately wreaked havoc upon the temple town, washing away everything that came in its way, but the Kedarnath temple.

Temple priests and pilgrims credited the survival of temple to be an ‘Act of God’, a divine intervention by Him to restore the valley back to its original form. However, intensive research and analysis of the Temple Precinct have confirmed that the temple’s architectural and structural innovativeness were the rationales behind its miraculous survival. Spatial planning analysis of the temple precinct has proved that the location chosen for constructing the temple by its ancient builders was, in fact, the safest spot in the entire valley, having an optimal slope gradient of around 5% and occupying a high ground to ensure its safety from impending floodwater and melting of snow.

Moreover, ingenious modifications in Classical Temple Architecture were made to add an extra degree of resilience to the structure. For example, the logic behind orienting the Kedarnath Temple along the north-south direction instead of the conventional east-west axis was to expose the temple’s shorter side to flash floods and debris flow approaching from the north, thereby protecting its longer and more vulnerable face. The temple ’s south-facing entrance further facilitates the entry of sunlight into the ‘mandapa’ as Kedarnath doesn’t receive sunlight from other directions, being hill-locked on three sides.

The shape, form, and proportions of the temple have also been acclimated to the site. The temple has a relatively short ‘shikhara’ which lowers the center of gravity of the superstructure, thus minimizing its tendency to topple in case of an earthquake or a flash flood. Furthermore, its inverted lotus-shaped dome doesn’t let snow accumulate during the harsh winter months and increase the dead load on the main structure. The plan of the temple is simple, symmetrical and based on the ‘mandala’(a Hindu symbol representing the cosmos) and its exterior walls are thick and serrated, enhancing load transfer to the substructure and making the building resilient against seismic and hydrological action. Geometrical Analysis of the Kedarnath Temple revealed a continuation of the ‘Golden ratio’ through its plan and elevations, enhancing its visual aesthetics as well as structural stability.

The Temple has been built on a huge stone-based plinth and a deep foundation, comprising of large boulders and stone fillers which reduce the ‘Inverted Pendulum Effect’, generated due to the action of seismic and other shear forces. Moreover, the high plinth level further raises the height of the temple and prevents flood water and snow from entering the temple premises.

The Structural System of the temple is a combination of trabeated and load-bearing, dressed stone walls, making the structure resilient against major earthquakes. The temple walls are made up of locally sourced Gneiss stones placed in Ashlar Masonry and held together by interlocking slabs and are up to 3 foot thick Additionally, a unique cementing material has been used comprising of locally sourced limestone, jaggery, lentil paste, etc. whose unique property is that it strengthens with passage of time.

The Kedarnath Temple has withstood the test of time and displayed a high degree of resilience in overcoming natural disasters and extreme climate owing to its strong Traditional Knowledge Systems and contextual adaptations, these technologies will be effective in the current age as well.

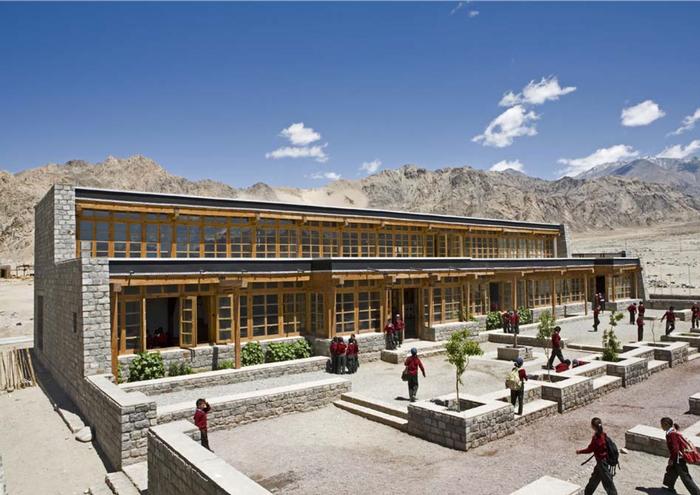

Moving further north of the Kedarnath Temple, sitting high in the Indian Himalayas among one of the last remaining traditional ‘Tibetan Buddhist societies’ is the ‘Druk White Lotus School’. It is a small Buddhist school in Ladakh under the patronage of the Dalai Lama and was founded by His Holiness the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa. Designed by Arup Associates, the school combines the best of traditional Ladakhi architecture with 21st-century engineering excellence and acts as a model for appropriate, cost-effective and sustainable development. Ever since its completion in 2013, it sets itself as an epitome of resilient architecture and aims to provide a high-quality educational environment which can equip new generations of the region to sustain the dying ‘Ladakhi Culture’.

Ladakh, a sparsely populated region in the Tibetan plateau is defined by the River Indus which runs along the Leh Valley at an altitude of 12,000 feet. The region experiences an extreme, ‘high-altitude desert climate’, with hot summers and frigid winters. With winter temperatures dropping as low as -10°F, the snow cuts-off this region from the rest of the country for around six months every year. Being on the leeward side, there is minimal rainfall as the Himalayas create a barrier to monsoon clouds. The main source of water is the winter snowfall on the mountains. In spring, the melt-water swells Indus and brings the valley to life. The lack of vegetation brings down the proportion of oxygen in the air to a great extent as well. Thus, the severity of climate and scarcity of water turn out to be essential determinants of Ladakhi architecture and of the Druk White school in particular; directing all decisions towards an energy-efficient architecture, mainly through passive solar systems.

The Ladakhi architecture exhibits Tibetan influences, especially from the Buddhist monastic tradition. Houses and monasteries (Gompa) are built on elevated south-facing sites using a combination of stone, wood and mud brick. The traditional vernacular is characterized by amply glazed windows divided into small panes, and by sophisticated surface decoration. Nevertheless, alike the Kedar Valley, most of the new buildings coming up here are generic RCC structures as well.

Earlier this year, we set off on our journey to the Druk White School. Upon reaching, we met the members of the ‘Drukpa Trust’, who gave valuable insights into the project. They also talked us through the school’s objectives. It was intriguing to find how the objectives weren’t just confined to the social facet, but also addressed the ecological and architectural fronts. Especially in a context as fragile as this, the school strives to define resilient design strategies, by taking account of both ecological and socio-cultural assets.

The school’s plan is based on the two traditional and universally valid configurations for design and planning- the ‘Nine-Square Mandala’ (similar to Kedarnath Temple) and the ‘Eight-spoked Dharma Wheel’, representing the cosmos and Buddhist teachings respectively. The complex consists of single-story buildings organized in parallel pairs, each framing an open, landscaped courtyard which eventually acts as outdoor learning areas during the summer months. In each pair, the northern blocks are enclosed on three sides by a masonry wall that provides protection from northerly winds. The southern facades are extensively glazed to provide passive solar heating and good levels of natural light. In addition, the roofs are designed to bring in additional daylight through clerestory windows. For optimum energy efficiency, the buildings in the daytime teaching area are turned 30° from south towards east in order to benefit from the morning sun. All other buildings face south, so as to maximize solar benefit throughout the day and store heat for the evening and night-time use.

The design aims to use locally sourced materials and building techniques throughout, alike the Kedarnath Temple. It incorporates stone, mud mortar, mud brick, timber, and grass, with careful assessment of the sustainability of their supply. Water is distributed through a solar-powered system, referred to as the ‘Energy Centre’, which contains the water borehole, water pump, solar panels, and batteries. Ladakh does not have a waterborne sewage infrastructure, thus, the school developed its own waterless solar-assisted latrine system in response to water scarcity. By improving the traditional dry latrine system, structures called the ‘Ventilation Improved Pits’ (VIP), are designed and tested using computational fluid dynamics. This system also produces compost and humus that can be used as fertilizer for the home-farm gardens.

The key aspects governing the structural design were earthquake loading, durability, and appropriateness. The buildings have cavity walls, with granite blocks joined together with mud mortar for the outer leaf and traditional mud brick masonry finished with clay for the inner leaf. The roofing system is the traditional Ladakhi-style heavy mud roof supported by a timber structure independent of the walls, which provides earthquake stability. Heavy timber portal frames provide the primary structure, while massive wooden joists support the traditional clay ceiling insulated with mineral wool. Some of the school blocks like hostels incorporate a thermal storage and delivery system called a ‘Trombe wall’- a thick masonry, coated externally with dark heat-absorbing material and faced with a double layer of glass creating small airspace. Heat from sunlight passing through the glass is absorbed by the dark surface, stored in the wall, and conducted slowly inward through the masonry. Adjustable openings on the top and bottom of the thermal storage wall allow heat transfer from the heated air cavity to the room inside. This increases the efficiency of the system and ensures constant comfort levels for the young occupants.

The visual effect of the complex, both from a distance and from within, is poetic. The dominant horizontality of the settlement is accentuated by strips of dark-colored glazing on the south facades. Within this composition of horizontally extended forms, the solar-assisted latrines stand as emblematic structures, contributing greatly to the settlement’s identity. As a self-sustainable construct and a lesson in design for pupils, engineers, and designers alike, the school successfully achieves a balance between community and environment while remaining true to its cultural context.

The quintessential learnings from the above two buildings can be summed up as follows: firstly, a deep understanding of the local climate, regional geomorphology, and ecological sustainability must be treated as prerequisites to any design, keeping an eye on future climatic trends of the locale. Secondly, cost-effective designs can be achieved by using locally-sourced indigenous materials that will boost the regional economy and fusing the local traditional knowledge with technological advancements. Finally, as architects, it is imperative to integrate the climate resilient built environment with the existing socio-cultural fabric to create a socially acceptable design that can catalyze upliftment of the society.

To summarize, the two buildings have portrayed immense resilience in effectively addressing their contextual issues for which their architects deserve due credit; having beautifully balanced the principles of climate resilience and sustainability along with the social art of architecture, they enabled the buildings to have a positive ecological and social footprint. Quoting Ban Ki-moon, ”Climate Change has happened because of human behavior, therefore, it’s only natural it should be us, human beings, to address this issue”. As architects, we should respect the power that has been bestowed upon us, and paint a piece on this global canvas that can be cherished time and again by us and future generations; and there wouldn’t be anything more impactful than developing communities resilient enough to fight this global threat of climate change.

*This essay is a tribute to the thousands of victims of the 2013 Kedarnath Floods. May the departed souls rest in peace.

References:

1. Cramer, Ned. (2017). Climate is Changing. So must Architecture. Retrieved from ‘Architect Magazine’ website: https://www.architectmagazine.com/design/editorial/the-climate-is-changing-so-must-architecture_o 2. Holland, Oscar. (2017). What Traditional buildings can teach architects about sustainability. Retrieved from CNN website: http://edition.cnn.com/style/article/vernacular-architecture-sustainability/index.html 3. Balamir, Aydan. (2007). On-Site Review Report- Druk White Lotus School. 4. Bray, John. (2005). Ladakhi Histories: Local And Regional Perspectives. Brill Academic Publication.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |