[ID:1162] The street in the body of the cityUnited Kingdom The United Nations estimates that the world population will increase to 9.2 billion by 2050 and for the first time in mankind’s history more than half of us will reside in cities. In London, growth is expected to be equivalent to absorbing the population of Birmingham and Leeds. As we head towards a new dawn of urbanisation, issues about how we create sustainable, efficient and healthy cities become more pertinent and must be addressed. A healthful environment by definition encompasses three factors of sustainability, livelihood and safety. By understanding and positively shaping our urban spaces, we can greatly increase the quality of our lives. As Jan Gehl states, “we shape cities, and they shape us.”

An engagement with the urban fabric toward a healthful environment must begin with the very veins of our cities; our public spaces and streets. The street remains the unconscious soul of the city. Historically, our streets have been an important catalyst for human interaction. Today, the street still remains an integral part of the city although its importance is sadly overlooked. As well as facilitating movement, the street is a place of exchange. The essence of the street and the city is its human vitality. A well-designed street provides a sustainable form of community; it invites citizenship, liveliness and humanity.

In London, streets account for 80% of public spaces. The value of good urban design and its power to drive change in the quality of our transportation systems, economic and sustainable development is an area that is greatly overlooked. However, measures taken have been quantitative rather than qualitative, and often neglecting the human dimension. In London, the deaths of 14 cyclists in 2013, with 6 deaths in less than a fortnight, provoked public debate that assessed how the city’s public spaces and transportation systems cater to the needs of its population. A report published by the Road Task Force for Transport for London, estimated that a quarter of all trips in London are made entirely on foot and that cyclists constituted a quarter of vehicular traffic at peak times in London. In considering these statistics, it becomes important to examine why these road users are still marginalized. Society’s love affair with the car can be traced back to the modernist rebuilding of our cities after the Second World War. In the modernist agenda, our future was to be dominated by the prowess of the motorcar; pedestrian and vehicular traffic were deemed incompatible. Here the modernist agenda, promoted by Colin Buchanan’s seminal report Traffic in Towns, promoted the segregation of motor and pedestrian traffic. However, half a century on, and with growing concerns for climatic and environmental issues, society is beginning to re-evaluate its relationship with the car. However, for meaningful changes to occur, we must consider how urban design can influence the way we travel and interact with one another.

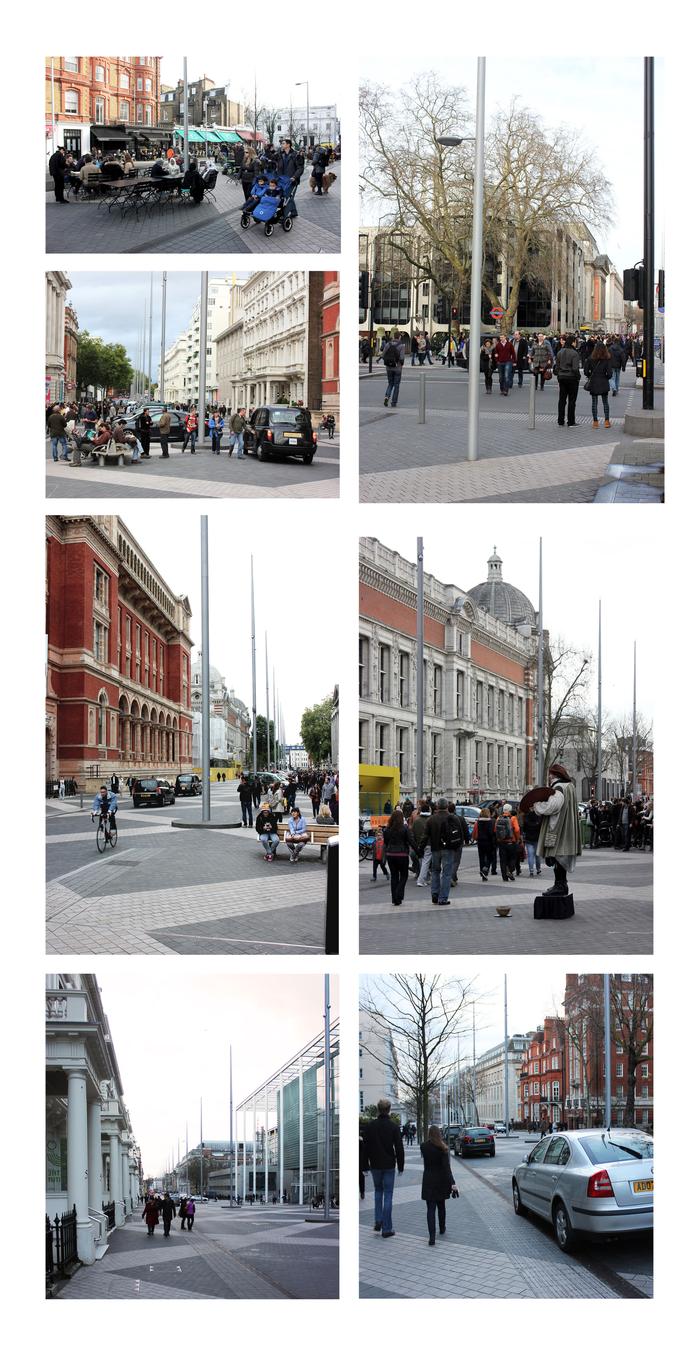

The redesign of Exhibition Road by Dixon Jones, completed in 2012, provides an example of a healthful environment that promotes human vitality and social interaction. The transformation of the 800-metre road that runs through London’s museum quarter into a shared space scheme reintroduces the human scale in urban design. Before its redevelopment, the foreground of this prestigious cultural centre was a sorrowful streak of grey divided into lanes for vehicular traffic and three lanes for car parking. Pedestrians were forced onto narrow footpaths with few opportunities to cross the cluttered road.

Shared space redefines the role of the street within the city as more than a tool for transportation but as a vital instrument for encouraging social interaction. Shared space seeks to improve pedestrian movement and comfort by reducing the predominance of vehicular traffic. It promotes informal social protocols where road users are encouraged to share a space rather than follow rules derived from assumptions about traffic behaviour, road safety and human behaviour. Shared space is not an entirely new construct; Mediterranean hill towns and marketplaces offer an informal interpretation of shared space. The conscious application of shared space can be traced back to Joost Váhl and Hans Monderman’s experiments in the 1970s.

The scheme implemented at Exhibition Road offers its annual 11 million visitors a dignified experience of the city. Arriving at South Kensington tube station, one approaches Exhibition Road from the south end. Here, on a sunny January morning, I observed the village-like atmosphere of the square at Thurloe Place. Visitors sat at one of the several cafes, all of which offered outdoor seating facing onto the square. The integration of the light wells associated with the underground station below within the design, provides further seating within the square. Pedestrians here are in transit, enjoying a leisurely pace and heading further along Exhibition Road or returning to the tube station.

The junction ahead signifies another condition. Vehicular traffic follows the road at Thurloe Place to exit the area or turns right to head further into Exhibition Road often travelling a slightly decreased speed, an acknowledgement of the fact that they are entering a shared space. Pedestrians are offered frequent opportunities to cross the road at the pelican crossing. Further north is Cromwell Road, the major A-road that bisects Exhibition Road. Again, pedestrians are offered opportunities to cross although this is a hurried and controlled experience.

Crossing Cromwell Road brings one into the museum quarter of the street. It is here, in the foreground of some of London’s finest classical facades, that the operations of the shared space can be fully observed. The 25 metre wide road is divided into two by a parade of lighting columns; the east side is for two way vehicular traffic, the west, is offered as a pedestrian comfort zone. The large footpaths combined with the greatly decreased vehicular speeds invite other road users to use the street more freely. During holidays, large groups can be observed crossing with ease thus regulating traffic within this zone. A vestigial kerb at the edge of the two sections in the form of a 800mm wide strip of paving, offers blind and disabled users comfort in navigating the space. The space within the two sections of the road is a mixed zone; people walk, stay and stand in this area. Cyclists freely traverse this zone. The benches offer a good place to sit, stay a while and enjoy the beautiful architecture or perhaps the street performer who entertains with his varied displays of magic.

The territory in front of Imperial College further north of the street offers a peculiar experience along the street. Perhaps it is the fact that it signifies a departure from the public institutions into a more private world or the monstrous scale of the main college building, but this part of the street seems unusually deserted. The lack of an intimate human scale in the facade of the building means the welcoming character of the street is somewhat lost here.

Finally, heading north towards Hyde Park, there is a sense of a more conventional road use. Both sides of the street are once again offered to vehicular traffic although pedestrians and cyclists are still welcomed. At night, with a decreased pedestrian presence, traffic travels at increased speeds. However, a successful lighting strategy illuminates the street, providing a sense of security and safety thereby maintaining the inviting nature of the street.

Studies conducted after the completion of the street, corroborate these observations and establish shared space as a positive contribution to the urban fabric. The overall experience of Exhibition Road is one of unison, understanding and community. The ground comprising 1 million granite sets form a unifying geometric pattern that successfully unifies a number of distinct territories along the street. Its physical design is a manifestation of the street’s ability to facilitate human interaction and promote a healthful environment.

It is this sense of unity and civility that should be applied to London’s wider transportation system, especially if one is to promote a healthful environment. The current provision for cyclists is confused and half-hearted at best and dire and deadly at its worst. The cycle superhighways, 1.5 metre blue painted strip reserved for cyclists, creates a “false sense of security,” as exemplified by the recent deaths of 3 cyclists. At Bow roundabout, a large roundabout system in East London, the failings of the cycle superhighways come to a head. Cyclists are left to fend for themselves alongside heavy traffic in what is a charged and confrontational atmosphere.

London is a city of complexities; it is a diverse and ever-growing metropolis comprising 32 boroughs, each of which regulates its own streets and roads. The geographical structure of London, as a series of smaller locales each with its own characteristics is an interesting and positive attribute of the city. However, in the provision of an effective transport system, this proves to have its drawbacks with a lack of a coordinated and coherent design profile that can be applied across the city. For cyclists, there could be a complete cycling route that connects the differing part of the city. The cycle superhighways are the beginnings of such thoughts but in their current state they are ineffective in promoting good cycling culture. Their narrow widths, a mere 1.5-metre strip, compared to Copenhagen’s recommended minimum of 2.5-metres, do not promote cycling as communal activity. The narrowed demographic London’s cyclists: young, male professionals clad in Tour de France ensembles, is a reflection of this crisis. In comparison, women represent 56% of Copenhagen’s cyclists . Young children are taken to school in cycle buggies while older children cycle alongside a parent on their own bicycles. Copenhagen’s 350km of cycle lanes offer adequate protection and safety for cyclists therefore inviting more people to cycle; 19% consider cycling their main mode of transportation compared to the United Kingdom’s 2.2%. The United Kingdom falls well below the European Union’s average of 7.4%. Such figures are disappointing for an economically thriving, matured democracy. As Enrique Peñalosa, Bogota’s former mayor credited with transforming the city’s transportation system remarks, “if all citizens are equal before the law, then of course a bus with 80 passengers should have the right to 80 times more road space than a car with one.” This is a reflection on the notion that our cities, transportation systems and public spaces express what we value as a society; these attributes are by definition the extension of a true democracy.

To achieve a healthful environment at an urban scale, one must engage with transportation. In London, the 1100 people, gathered at Hackney Empire for the recent screening of Andreas Dalsgaard’s, The Human Scale, exemplifies the growing interest in this topic. A presentation by Gehl that followed laments the slow progress in making London a liveable city. Ten years after the publication of Towards a Fine City for People: Public Spaces and Public Life – London, many of its targets have not been achieved. One must ask why?

In Curitiba, a change that began with Jamie Lerner as mayor in the 1970s, has transformed the city into one of the world’s most liveable urban spaces. The establishment of a comprehensive bus transit system and several kilometres of protected cycle routes have transformed the lives of city’s 3.2 million inhabitants. The common themes throughout this transformation are simplicity, expediency and practicality; themes that are not captured in recent proposals to aid London’s cycling crisis by Lord Foster. Foster’s Skycycle proposes a network of cycle paths elevated above London’s railway lines. Accessed via 200 entrance points, it could accommodate 12,000 cyclists an hour with 6 million people falling within a Skycycle route. However, at £220 million, nearly £34 million per kilometre, the estimated cost of Skycycle would be almost a quarter of the budget for the mayor’s Cycling Vision, a plan to improve cycling conditions over the next 10 years. More concerning than the economic challenges that the scheme presents, are the alarming issues it raises about London’s cycling culture. This scheme promotes an unhealthy and exclusive view of cycling; an activity for the young, 40 kilometres-an-hour cyclist who demands the right of way, believing that children and older cyclists are as bad as cars. Skycycle is the reduction of cycling to being purely about a mode of transport. In actual fact what cycling offers, is the freedom to explore the city’s complex beauty at an intimate, human scale. Curitiba exemplifies what can be achieved with a minimal budget, a sense of urgency and masses of creativity - an approach that London could learn from. A significant issue for London is the highly bureaucratic planning system which stifles creativity and stalls change.

Schemes such as the mayor’s Mini Holland project provide some hope. The project will fund the transformation of four outer London boroughs in cycle-friendly places and improve connectivity to the centre of London. Kingston-upon-Thames, an area I know intimately as a cyclist in my years as a student is one of eight shortlisted for the scheme. Proposals such as establishing strategic connections that will provide a network of cycling infrastructure and creating a car free plaza at Kingston station will invite more people to cycle and walk. However, schemes such as these should not be viewed as a lone solution; they must be implemented along with other measures toward a healthful city. Cycling should not be considered a lone activity; it must be better integrated into other modes of transport. For instance, the ability to take your bicycle on a train or tube should be further promoted. This will encourage more people, especially those travelling into the city from the suburbs, to cycle more often. Furthermore, improving safety measures for cyclists by implementing traffic control measures such as allowing cyclists to move earlier than cars at traffic lights, could make it considerably safer to cycle around the city. Moreover, building on successful cycling initiatives such as the Cycle-to-Work scheme would encourage more people to cycle.

As illustrated in Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, there are many lessons to learn from observing our cities. From the observations that I have made in my city, London, it is clear that there is a case for the reappraisal of our urban fabric, namely our streets and transportation systems, both of which are crucial in the design of a healthful environment.

The human dimension must remain an integral aspect in planning the urban fabric. We must reinstate our street as the soul within the body of the city. The street must be reconquered, reinstated as a place for exchange and human vitality. Furthermore, the provision of an adequate transportation system that is fair for all road users is essential to the redefinition of our cities. In both solutions towards a healthful environment, equality, community and understanding remain integral. As a community - designers, politicians and the public, we must set out a clear vision and purpose for our cities and implement actions that will achieve these aims. But above all, we must remember the definition of a healthful environment; it is humanist in purpose and environmentalist by consequence.

Bibliography

United Nations, ‘World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision, Highlights’ (2012)

Roads Task Force,’ The Vision and directions for London’s street and roads’ (2012),

Gehl, Jan, ‘Cities for people’ (London: Island Press, 2010) p. IX

Roads Task Force,’ The Vision and directions for London’s street and roads’ (2012),

Roads Task Force,’ The Vision and directions for London’s street and roads’ (2012),

MVA Consultancy, ‘Exhibition Road Monitoring’, (August 2012),

‘Mayor urged to prevent more cycle superhighways deaths’, (2013),

Hill, Dave, ‘Interview: Jan Gehl on London, streets, cycling and creating cities for people,’ (January 2014),

‘Why is cycling so popular in the Netherlands?’ (August 2013) ,

Pagh, Jesper, ‘The main cause of the problems in cities is inequality: interview with Enrique Peñalosa’ in Arkitektur DK, (2013), p.55

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |