|

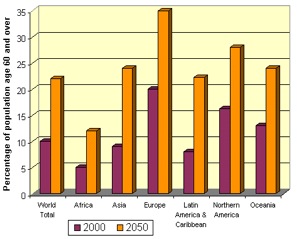

Valerie Fletcher: The Role and Power of Design in Social SustainabilityThe Role and Power of Design in Social SustainabilityValerie Fletcher (Originally published in Abacus, A Bi-Annual Journal of Architecture, Conservation and Urban Studies, India, Monsoon 2007.) A global dialogue has begun with profound implications for architecture and design. The UN’s World Health Organization (WHO) posed a challenge to designers with its redefinition of disability as a contextual experience in 2001. Though WHO policy would not ordinarily be relevant to designers, this is different. WHO defined disability not as a phenomenon of a fixed segment of the population but rather as a universal human experience. It is not about some vague ‘them’ but rather about all of us. Most significantly for designers, it reframed disability as a by-product of the interaction between the individual and the environment. When we design the environment to anticipate a spectrum of potential limitations, we have the power not only to minimize disability but, potentially, to enhance everyone’s well-being and performance. The UN’s 191 member states adopted the new definition, called the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) after ten years of development, making this a framework for research and collaboration globally. The timing is just in time to respond to new population realities. The aging of the world’s population is the tsunami of 21st century demographics. Each month the number of people 60 and over increases by 1.2M. By 2050, for the first time in history, the old will outnumber children. The most dramatic changes are in the developing world. It is projected that there will be 400M Chinese 60+ by 2050, the same year that the entire Japanese population is expected to be no more than 69M. In contrast to the rallying cry of environmental sustainability, driven by the need to address the failure in the 20th century to exercise responsible stewardship of the planet, design for social sustainability responds to a successful accomplishment of the 20th century. Longer lives are one measure. The other is survival of maladies that would have cut short our lives a generation ago. Now it is commonplace to survive congenital abnormalities, catastrophic illness or serious injury. Science has delivered not only the promise that many of us will live decades longer than a century ago but also the reality that many of us are survivors, grateful to live but living with some limitations. The only rational response to the changed human landscape must be sense of urgency that nothing but a wholesale rethinking of our responsibility and power as designers. There is no time to waste replicating old solutions. We must invent solutions for a range of human ability in every project from urban infrastructure to workplaces, homes, schools, cultural and entertainment venues. The ICF calls for designers to go beyond barrier removal and identify the facilitators of well-being and performance. That charge is incorporated into the 2007 UN Treaty on the Human Rights of People with Disabilities. As of today, 90 nations, including India, have signed the Treaty. It is a time for designers to lead a new vision of the potential of design to transform the human condition.

|