|

In the "Design" realm of architecture, it is easy to relate social responsibility and low cost projects with soullessness and creative handicap that does not elevate the architect to recognition. In today's competitive race towards fame many architects, myself included, shy away from the challenge of sharing their talent to better the lives of many who, unlike most clients, may actually appreciate their efforts to the core of their being.

I was initially approached by International Child Resource Institute (ICRI) in Berkeley, California, a couple of years ago to design a pre-school in Dalian China for a prominent local developer. We inherited the project from another architect who allowed the tiny fee to blind the enormous opportunity this represented. After a couple of successful trips to Dalian and three months of intense, unconditional and cultural immersion into the project, it was approved and is now awaiting construction. One resulting opportunity was being asked by ICRI, with whom our relationship had flourished by now, if we could help them design prototypical kindergarten/child care centers for Zimbabwe. The word Zimbabawe itself, we learned, actually means "Shona house of stone."

After being invited by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and community-based organizations in Zimbabwe to collaborate and work towards serving children and families in that country, ICRI traveled there during the spring of 2005. Learning about the plight of orphans and vulnerable children, and the current political and social economic challenges faced locally, ICRI made the decision to partner with members of the community in rural and urban locations to implement and provide technical assistance and capacity building to already existing programs. During a visit to the province of Buhera, the local government approached ICRI to develop and implement model community-based child and health care centers to serve orphans and vulnerable children ages 0-6 in the region.

The following conditions affecting children and families are what prompted ICRI's involvement in Zimbabwe:

- A total of 14 million orphans have been reported due to the AIDS/ HIV epidemic globally, of whom1.6 million have been reported in Zimbabwe.

- The World Bank has reported that Zimbabwe receives the lowest amount of donor aid amongst the 15 countries of the world with the highest HIV/AIDS prevalence rates. To illustrate, $ 4/per person per year of funding is allocated to persons affected by HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe compared to $180/per person per year in Zambia or Kenya.

- Every day at least 10 cases of child sexual abuse are reported, with an unknown volume of such cases going unreported.

- Due to high rates of inflation, several NGOs have pulled out of Zimbabwe and many programs that initially served orphans and vulnerable children have ceased.

The resulting community-based child care and health centers would be developed to create a safe, supportive and stimulating environment for orphans 0–6. These programs would relieve the burden of care from extended family members and school-aged children who care for their younger siblings, potentially preventing abandonment or maltreatment. Child care and health services would be integrated into one facility that holistically addressed the needs of families for child care, nutrition, basic health treatment, psychosocial support, and material assistance.

The child care center would be designed to provide optimal early childhood education and remediate developmental delays. The space would be set-up to be inviting to children, with learning zones for different play opportunities. Child development assessments would be conducted for each child upon enrollment in the center. Based on these assessments, staff would identify and remediate delays through developmental play.

ICRI would provide child care, health, and social services to 150 children and their families at an initial site, with planned expansion to additional sites.

Contrary to the project in China, which enjoyed generous constructions funds, we were informed that these childcare centers would need to be built for a few thousand dollars. The challenge was thrilling as was the hope that the impact of our work might actually better children's lives half way around the globe. Putting fees and ego aside, this project filled a much larger void inside; that of giving reason for being and the opportunity to use whatever modest talents I had to challenge Architecture and Design away from its perceived "Men's Club" exclusivity and the notion that inexpensive could not be inventive but only stereotypically dreadful and bland. Though it may sound like a platitude, I wanted to find color in my approach, bring light where only darkness reigned, and help sculpt beautiful moments in time for kids who dare not dream of a better place and future.

An imaginative, less timid approach would ensure that the enchantment of childhood was amplified, and remained as a positive and potent memory for the individual to carry through life.

It is my belief that, if the environment does not challenge children sensually then they inevitably absorb the view that it is of little or no consequence.

"The essence of kindergarten architecture is the notion of creativity, imagination, and fantasy. The challenge for Architects is not just to design functionally appropriate spaces to support the children's activities, but also to engage their imaginative powers in a radical way."

The term 'Kindergarten,' which originally derived from the notion of the school as a metaphorical garden, alludes to the idea of children as unfolding plants...

"Children, like budding lilacs, should be placed in the tropical warmth of a greenhouse, to be nurtured through the cold winter months..."

How often does one have a chance help provide such a garden, where existence and occasional dreams hang at the mercy of ruthless politics hopelessness and poverty?

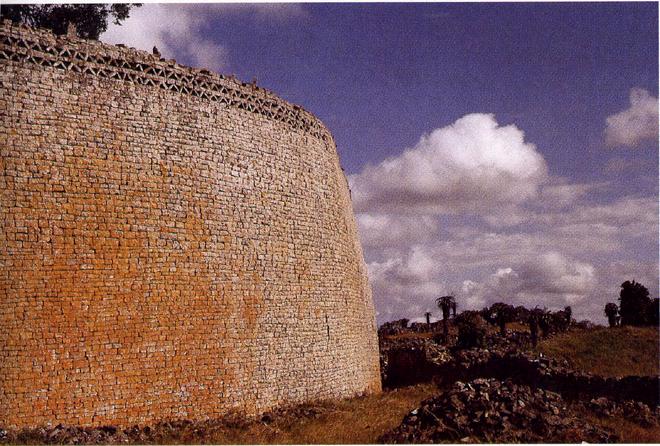

The seeds lay in Zimbabwe's indigenous architectural heritage. Skipping over the colonial signature and influences that have assumed authenticity over the years, I discovered unspoken beauty in the architecture that preceded that period. A subtle beauty embedded not only in the simplicity of the materials and construction but also in the fluidity of the forms that were both possible and affordable. By drawing from that rich heritage and plagiarizing it some, I came up with the "Pod" design; a spherical and domed structure that paid homage to its ancestry and allowed for the perfect shape for a pre-school or kindergarten. As we had done for our China project we weighed mechanistic modernism against organic spirituality and opted for softly curving architecture that is welcoming and encourages movement and exploration in and around the building, while providing a vivid yet calming language. Rising from the land, the pods embrace past and present through their simple yet evocative architecture and natural palette of materials. This natural response dissolves the institutionalizing nature common to such social architecture. It encourages children to play and develop their own sense of independence within a secure umbrella.

The perception of the Kindergarten as a sort of 'Hospital with toys' should no longer be valid and much recent work by kindergarten architects and designers shows the possibility of architecture, which is a reflection of the enigmatic notion of education through play.

To keep construction cost down and allow for local labor skills, the pods are designed to be built from readily available materials and methods. Salvaged chiseled stone or white washed adobe brick adorn the outer hull gently bowing into an "Igloo" shape. The latter is supported on the inside with thick radiating mud walls and ceiling beams connected to a central compression "O" ring in the middle to create a dome; the straw roof now being substituted with corrugated metal lays on top leaving a gap, the thickness of the beams, between the roofing material and the top of the walls for ventilation. The floors, made of compacted earth and/or concrete and covered, if possible, with cork and straw allow for the setting of different activity "Zones."

Features include:

- Window and door openings are designed so as to substitute glass with oversized timber screens to prevent looting at night and allow for ventilation.

- Water basins for outside water play can be built out of concrete if available, but can also be formed with adobe, bricks and mortar.

- Power generators and underground water tanks would allow for a certain level of autonomy and self-sufficiency.

The pods are designed to allow for different school configurations. In one concept, a larger pod houses the whole school under one dome, with the classrooms, kitchen, library, music room and other spaces radiating around a central common play area crowned by a small opening to allow light and air in. A large opening to the outside provides access to an outer ring of water play areas, a playground and bicycle tracks.

The large door openings bring the indoor and the outdoor together to serve as a large stage and amphitheater for school gatherings, plays, music or play.

Another concept looks at smaller pods as individual classrooms radiating like satellites (up to 6) around a larger central one; the latter allowing for a larger landscaped interior courtyard with a larger circular overhead opening and radiating spaces for the library, kitchen, music room…Outside water play areas, playgrounds and bicycle paths ring and weave around the individual satellites.

In either case, each classroom consists of discreet zones for different activities:

- Entry Zone (books and garments storage)

- Wet/Messy Zone (water play and kitchen activities)

- Active Zone (circle time, block and wheel toys, art, creative and dramatic play and music)

- Passive and Quiet Zone: (pre-reading, math, manipulative, puzzles and story telling)

* * *

The challenge in Zimbabwe and other impoverished countries around the globe is to bring the needs of children and projects like this one to the forefront of priorities and policy; to have their voices heard amidst the sounds of endless wars, broken promises, corruption, the overwhelming other needs and the needs of so many others, the lack of resources and, above all, the lack of empathy and concern by most of us.

I am very fortunate that through some unique set of circumstances and turn of events, I was introduced to ICRI and the good they spread worldwide. Having grown up in war myself, my efforts here mean much more to me than providing architectural services. They have given soul to my passion where passion and soul are more than often sidelined in favor of the bottom line, be it financial or the capitulation to architectural trends, both of which I am an occasional victim of.

I don't know when or whether this project will surmount the obstacles I mentioned above without intense political maneuvering and perseverance. What I do have control over though, on this brief journey that ties us all together, is my commitment to share my humanity as a finite fellow traveler where it is needed most, where what we take for granted remains for many an unattainable dream.

|

Mud Shonas

debbas.jpg)

Ancient Conic Tower

Prototype Childcare Center

Structure for Mud Shona Walls

Ancient Enclosure Walls of a Shona Village

Prototype Childcare Center

|