[ID:1478] Architecture Or (r)EvolutionIndia Architecture or (r)Evolution

The Santhals, an agrarian tribe settled in Jharkhand for several millennia, were the first to witness the ravages of unchecked industrial growth on their sacred land. A major part of the Indian uranium manufacturing industry relies on the mines at Jadugoda. In the late 1960s, after the introduction of the mines, Jadugoda, derived from “Jaragoda”, meaning a bountiful forest, was rapidly transformed from a land gifted with nature’s bounty to a pollution spewing industrial hub.

Uranium concentration produces toxic waste. This is collected in artificial water bodies known as tailing ponds. Three such ponds exist in Jadugoda, and there are plans for a fourth one. People who were initially seduced by the lucrative economic opportunities the mines offered, soon found acres of their agricultural lands submerged by the tailing ponds. Residents of the villages Chatigucha and Tuardongri were the most affected due to their proximity to these water bodies. Unwarned of the side effects, devoid of any other source of water, the villagers used contaminated water for their daily chores. Radioactive contamination has ever since entered their food chain. Cancers and diseases have cast a shroud of eerie silence over their once vibrant and lively neighborhoods. The cost of treatments far outstrips their income and these tribes, once content in their modest environs, have been driven to poverty and dismal living conditions.

“I have felt the pain and sorrow that the people of my region bear – the regret of being born in Jadugoda, the fear of living in a radiation zone and desire, wish and hope for relief.” , writes Ashish Birulee.

Mr. Amitava Kumar, in his passionate article “ What links Japan and Jadugoda” ( The Times of India, July 14, 2013) quotes Ghanshyam Birulee, an activist, on his future goals, “rehabilitation for all those affected by uranium poisoning; medical treatment and compensation for the sick; ensure safe mining; and lastly, carry out uranium waste disposal in accordance with international laws.”

Santhali villagers, despite growing urbanism, have maintained their traditional lifestyle and building techniques. Extensive use of materials and colours adorns their architecture with a mesmerizing pallete of textures. The cognitive articulation in their spaces awakens embodied archaic memories and one can very intuitively embrace their pattern of building.

In December 2013, on a visit to Jadugoda, I met Mr. Ghanshyam Birulee and his son Ashish. He along with other activists of the Jharkhandi Organization Against Radiation ( JOAR) elucidated the changing dynamics in the social fabric of Jadugoda. The plight of the tribals has been accurately captured by Ashish’s gut- wrenching visuals. His work reveals the stark contrast between that which is beautiful in Jadugoda, and that which is beastly. Mr. Ghanshyam Birulee affirmed the need to urgently relocate those affected.

After visiting the villages personally, and looking at the plight of the villagers, one felt that a sensitive design proposal is the need of the hour. The interaction with the locals offered a rare insight into their lifestyle.

Hence, as a part of a final undergraduate design studio, I decided to address some areas of this problem within the scope of an architectural intervention. This intervention aims to relocate the two villages to a safe distance and at the same time become a driver for socio economic upliftment. Along with Mr. Birulee, a site for relocation was identified. There are already talks in place to use the abovementioned site for the same.

The Santhals are a close knit community. Entire villages comprise of one or two families and their extensions. This natural cohesiveness is reflected in their architecture. Their homes are planned around the daily chores of their womenfolk. These built spaces are accretive, a delightful interplay of volumes. Their houses compulsorily have a front verandah, decorated with bands of naturally synthesized colours and sometimes, embellished with mirrors and overlaying patterns. The plinth of their houses projects into the verandah and serves as a platform for visiting salesmen on cycles to display their wares. The houses line a primary access road. The verandah therefore serves as a space for the house ladies to feel a sense of security while dealing with outsiders.

Figure 1 highlights the current trends in low cost building in Jadugoda. This new construction is detached from the traditional building techniques and sits disharmoniously with the systematically constructed town areas post the 1970s. Eclectic billboards unceremoniously crown haphazardly mushrooming concrete construction. Large and gaudy aluminium composite panels have replaced the subtlely coloured walls.

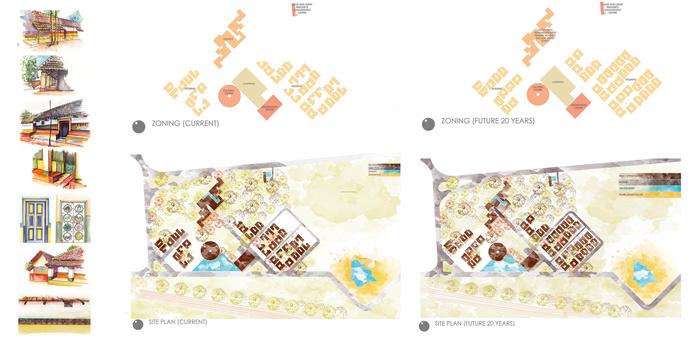

The design intervention, therefore, strives to construct a new significance. Figure 2, highlights a designed layout plan for the relocation of Chatigucha and Tuardongri. This project is strongly set in the context of time, with a vision that the neighbourhood will grow over a span of 20 years. The chief highlight of this plan is its incremental housing. The houses can be built in stages and the store rooms can be added later. The functional demarcation of spaces within the designed houses is similar to the existing spatial configurations in Santhali homes. The houses have deliberately been designed with clear visibility axes, with their backyards facing a shared open space. Open pockets of space, created in the heart of a low rise residential volume, has immense potential to facilitate interaction and combined activities. In this design these pockets have been used to create a shared biogas plant, a compost pit and a playground for toddlers.

The informality of this space allows the residents of the houses lining it to customize it the way they like. They could go ahead and plant the trees they consider sacred and set up their own shrines or they could even convert it into a vegetable patch, the possibilities are endless. The lady of the house can sit in the courtyard of her house and go about her business and yet have an eye over her child playing in the little informal garden beyond her poultry shed. She can discuss her household with her neighbor, who may most likely be her sister – in – law while they tend over their livestock. This softening of thresholds between the houses and the shared courtyard has been done purposely to ensure that the ties between neighbours remain intact. One of the major reasons why most rehabilitation schemes fail is due to the formalization of these very ties. Therefore, these houses have been carefully crafted to enable conservation beyond materials.

Hannes Meyer, Director of Bauhaus (1928 – 1930) rightfully articulates , “ Architecture is a process of giving form and pattern to the social life of the community. Architecture is not an individual act performed by an artist- architect and charged by his emotions. Building is a collective action.” The sense of belonging and intuitive connection to a space built by one’s own hands is unmatched and hence, illustrated in Figure 3, is a template created for the villagers to design and accessorize their houses in tandem with the architect. The motive behind this template is to reduce the sense of alienation. The villagers can amass the endless permutations at their disposal can create unique looking houses.

The site contains a natural lake in the far south. Though it is slightly contaminated, it would be criminal to ignore it. The lake’s toxicity , hence, can be highlighted by planting sunflower fields along its periphery. Sunflower roots help in neutralizing radioactivity and have to be incinerated periodically. The bright yellow flowers will serve as an unmistakable signage of the pollution in the lake. Over a few years, they will clean the lake and the periodical burning of sunflowers could be the start of a new tradition amongst the villages.

While designing this relocation project, it was kept in mind that a large part of the population has been scarred irreversibly. Therefore, Figure 4 illustrates the design of a hospice. The hospice has been designed with ample courtyards that provide visual connections across the building. The corners have been opened to create workshop areas and dining spaces with an unbridled view of a thicket. The building has been kept austere in terms of its form and materials. However, subtle colour accents inspired from the traditional Santhali homes have been introduced along the building to add a little cheer. The primary building material is Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks (CSEB). These blocks are the size of bricks and are made by compacting and chemically stabilizing the earth on site. The excavated areas can serve as the trenches for foundations and the rest can be used to create a water body with lotuses. This water body will passively cool the building and will contribute to the landscapes created.

The hospice building has been planted amidst a small thicket to keep it as close to the elements as possible. These trees also create a natural visibility barrier, giving the patients privacy. Apart from offering a sanitized and dignified environment for the agonized and diseased, it also offers job opportunities to the villagers. There is a strong possibility that the hospice may not be required after the mines close down. Therefore, the building can be then adaptively reused as a vocational training centre or primary school.

The Japanese philosophy of Wabi – Sabi, which is best defined as “ the art of all things imperfect, impermanent and incomplete “ has been re – contextualized in terms of this programme and has been applied abundantly. In view of the hospice design, it was of utmost importance as the building primarily needs to offer spaces that can comfort as well as provide room for contemplation. Hence, the scale of the hospice has also been kept very close knit and as intimate as possible. Currently, those affected receive a grant from the government as a disability pension. However, every month they have to travel a few kilometers to meet the Pension Officer to complete some formalities and receive their grant, much to their inconvenience. Most of the compensation they receive gets used up in their travel. Instead, if the hospice were to be constructed, the Pension Officer could make a monthly trip to the hospice and complete his formalities there. The pension amount would then be put to its intended use.

The very last design element is a forum of public place with different meanings. The Cultural Centre, replete with workshops and galleries aims to translate into an icon of hope by its sheer scale. The function of this building is to provide a platform for interactions at two levels- one, for the NGOs to interact with the villagers and for the villagers to interact amongst each other. The workshops and galleries have been designed to re- sensualize the relationships between ancient Santhali traditions and their current interpretations and integrations in the villagers’ lifestyles. Inspired by a traditional “Guyu”, which is a den made of hay, the corridors of the cultural centre have been designed in the form of progressively dilating semicircles. A walk through this spatially hypnotizing passage, lined with memoirs of their rich culture is meant to subconsciously evoke the splendor of their tribal ancestry. Far from a repository of artefacts, it provides spaces for engaging in handicraft making and celebrations of festivals.

The outer periphery of the Cultural Centre has radially arranged partitions which will serve as a venue for the weekly market. It is flanked by an artificially created water body in the south- west, an open ground on the east and the sacred grove of Sal trees in the north. The Santhals worship nature and their festivals encourage them to engage with all the elements of nature. The large ground on the east is essential to Santhali festival celebrations as dancing in a circle is an important part of their festivities. The Sal grove is where they would traditionally hold their rituals.

Poverty is a multi-dimensional social problem. However, in the case of Chatigucha and Tuardongri, design based interventions can provide solutions within the scope of architecture. This design confronts the same by identifying territories of concern and by acknowledging the embedded fabric that makes the Santhals what they are.

As of today, the air is heavy with pessimism in both Chatigucha and Tuardongri. The need for cheap electricity for a large nation weighs the problems of these two small villages as collateral damage. Though their problems have been acknowledged, the steps taken to rectify the same are too few. The charm of the lucrative money in mining has evaporated. There is poverty and then there is inflicted poverty. Inflicted poverty is a plague that paralysis the mind, body and soul of people and the communities suffering from the same become breeding grounds of unrest.

Le Corbusier in Vers Unne Architecture , 1923, rightly says, “ We are dealing with the urgent problem of our epoch….The balance of society comes down to a question of building. We conclude with these justifiable alternatives, Architecture or Revolution. Revolution can be avoided.”

Architecture, being a permanent edifice can help create icons that have a positive impact on those affected. It can stand as a symbol of hope in the face of adversity. Those affected need to engage directly with the process of rebuilding their lives to imbibe a sense of pride at every stage of design execution. Community architecture is in itself a show of solidarity and a safe channel to mobilize all the energy that political unrest churns. Architects can accelerate this shift. To that end they should ensure that design, especially in the case of poverty inflicted users, is approached with pride, not pity.

Citations:

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/stoi/deep-focus/What-links-Japan-and-Jadugoda/articleshow/21065173.cms

Buddha Weeps in Jadugoda, Shriprakash

Growing Sunflower in Jadugoda- Nitish Priyadarshi

Jadugoda Photo Series – Ashish Birulee

Study on health status of indigenous people around Jadugoda uranium mines in India- Indian Doctors for Peace and Development

Study of a Traditional House:

http://www.academia.edu/3887802/SUSTAINABILITY_OF_RURAL_MUD_HOUSES_IN_JHARKHAND_ANALYSIS_RELATED_TO_THERMAL_COMFORT

http://www.archinomy.com/case-studies/686/traditional-house-in-jharkhand-india

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |